Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa – Wellington

New Zealand’s national museum and art gallery, Te Papa is a veritable ‘treasure box’ of art and objects telling the story of Aotearoa.

A History of New Zealand’s National Museum

In my last post, we looked at how to spend 48 hours in Wellington, including several museum recommendations. Today we’re going to deep dive into one of those museums, the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (commonly referred to as Te Papa). Only, it wasn’t always called that. So let’s go back to the beginning.

New Zealand first got itself a national museum as far back as 1865. At that time it was the Colonial Museum, handily built on what is still Museum Street in Wellington today. The collection was predominantly scientific but also included a number of other acquisitions in various categories. In 1907 (the year New Zealand became a Dominion) the Colonial Museum became the Dominion Museum, with a broader focus. A national art gallery opened its doors not too long afterwards. The two came together in the museum building in 1934, and moved into new premises in 1936. Then there was a temporary waterfront art exhibition space from 1985 to 1992. But by this time the museum was in need of a rethink. The field of museology had moved on a lot, as had New Zealand as a nation.

And so, after moving a hotel out of the way, a new museum began to take shape on Wellington’s waterfront. Built on reclaimed land, it required a careful approach to compacting the underlying soil and earthquake-proofing the foundations. It also required a new, bicultural identity, as part of a wider recognition that iwi must be involved in the interpretation and care of all taonga.

The new national museum and art gallery opened its doors in 1998 with a new name: The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. The name selection was perhaps not the best example of bicultural cooperation, but ‘Te Papa’ is today a beloved institution. The Māori name can be translated as ‘container of treasures’.

A Container of Treasures: What to Choose?

The remit of a combined national museum and art gallery is quite broad. Thinking about another country I’ve visited with a comparable duration of human settlement and interesting geology and geography, Iceland comes to mind. The parallels aren’t exhaustive: New Zealand is a bigger country with a bigger population, has a different cultural makeup and experience of colonialism, etc. But there are parallels nonetheless. And in the case of Iceland, the subjects Te Papa covers are split across several institutions, if we count the National Museum of Iceland (which is mainly social history), and galleries of art and photography.

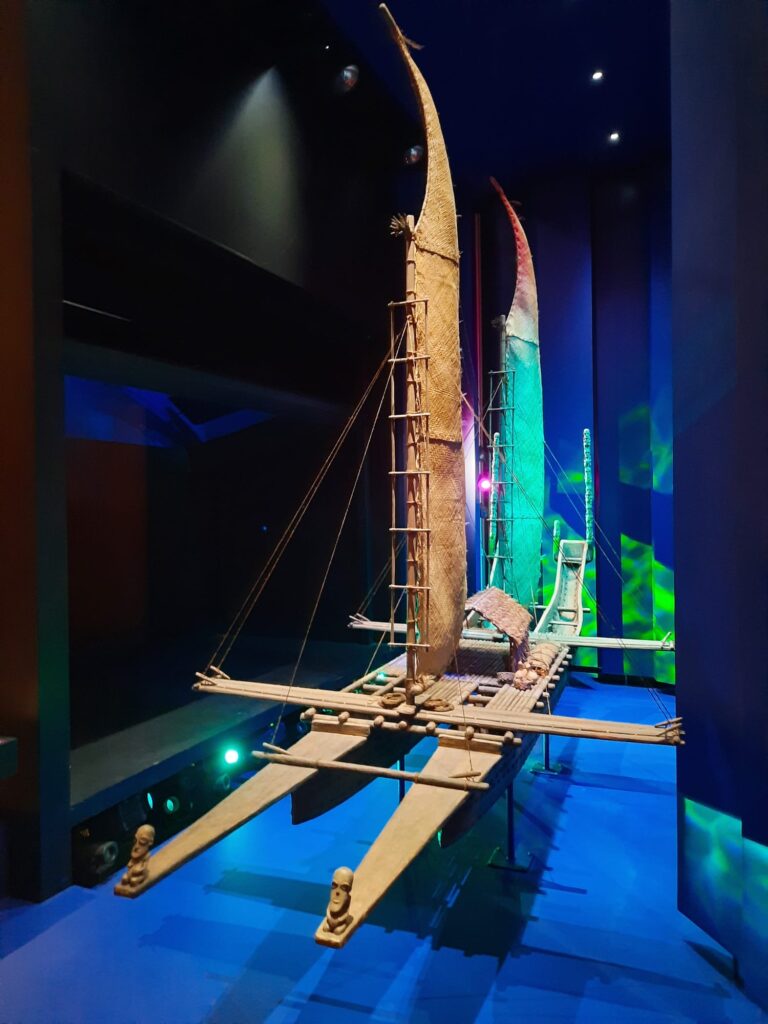

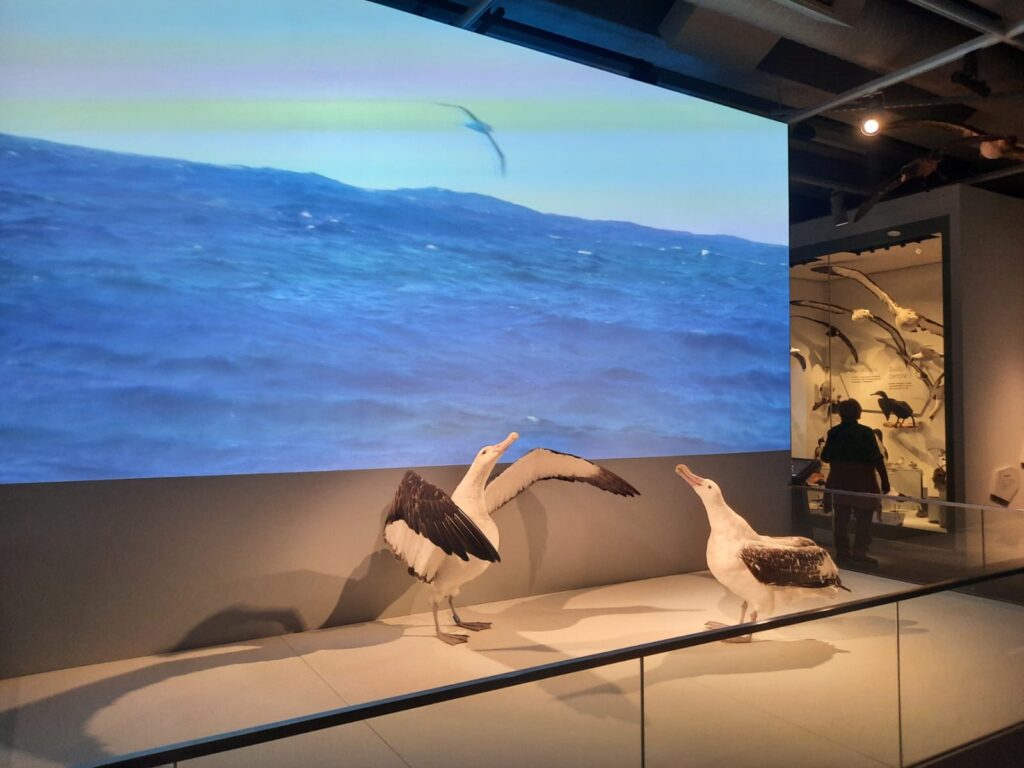

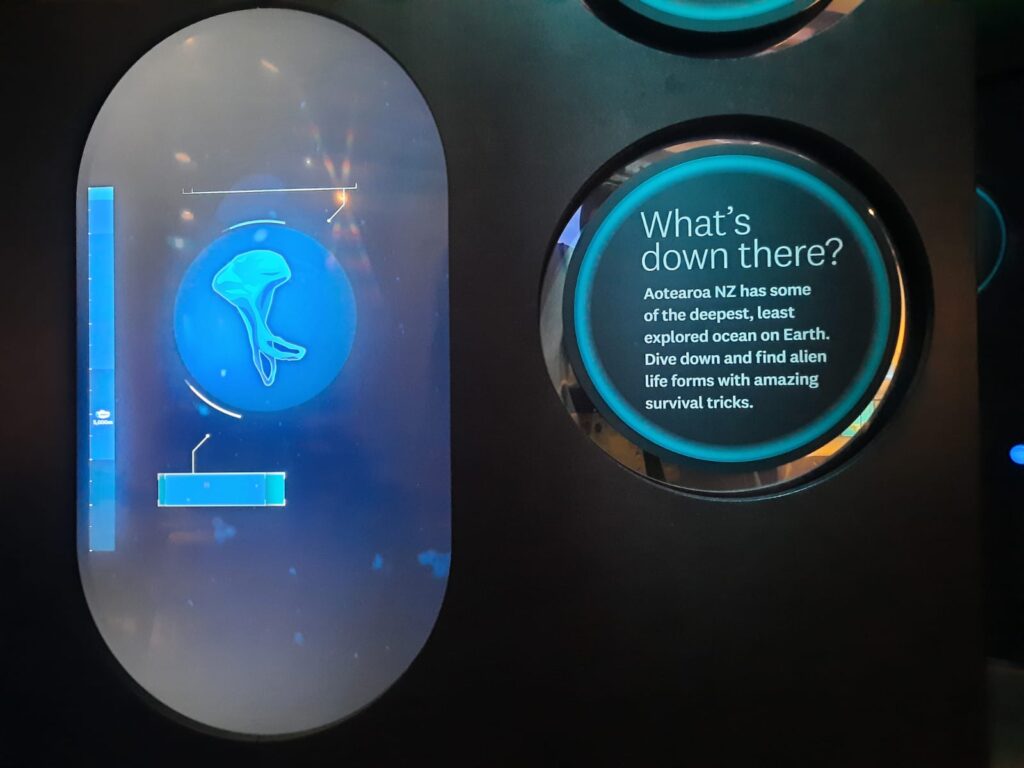

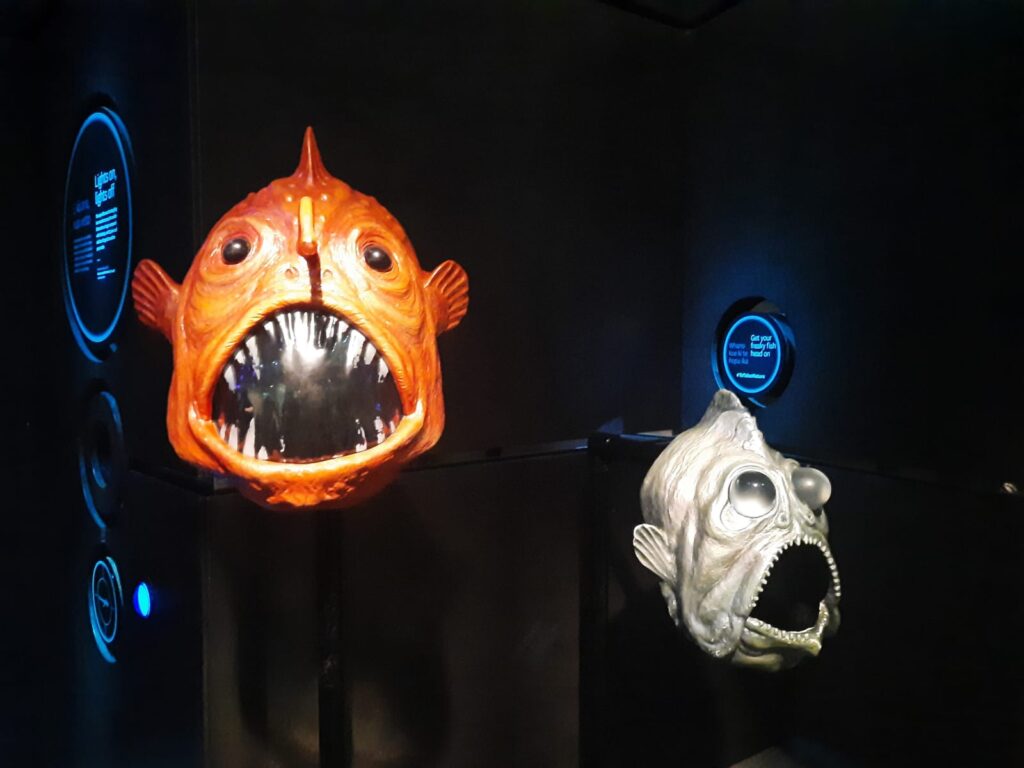

So Te Papa has its work cut out for it. To cope with telling the stories of a nation under one roof, it of course breaks out different themes. Going from the ground floor up, there is an outdoor area with a ‘bushwalk’ experience; a display on New Zealand’s natural environment and another on WWI; Whāngai, Whenua, Ahi Kā which looks at people’s impact on the land; a people-focused floor with exhibitions on Māori, Pasifika peoples, immigrants, refugees, and the Treaty of Waitangi; and finally art. Or normally art on the top floor, anyway, but it’s currently undergoing renovation. There are also a couple of standalone exhibitions of objects with great cultural significance to New Zealanders. One such is the record-breaking Britten Bike. Another is the skeleton of 1930s racehorse Phar Lap.*

Te Papa is free to visit for New Zealanders and New Zealand residents. Tickets for international visitors are valid for two days. In theory this gives enough time to see absolutely everything on view. In practice, you probably want to focus on a few areas. During our visit, as you will see from the photographs, we wandered through the fourth floor displays on different peoples, had a brief foray into the natural world, and spent time in Gallipoli: The Scale of our War.

*As an aside, Phar Lap’s skeleton, heart and hide are all preserved in different museums.

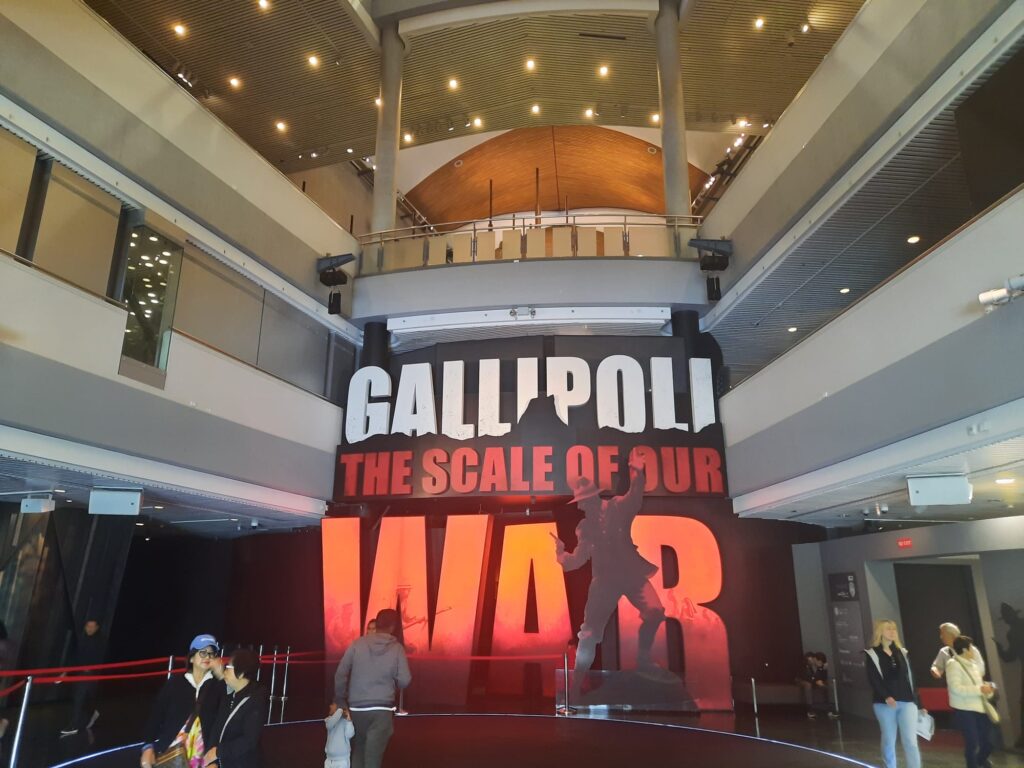

Gallipoli: The Scale of our War

That brings me nicely to a discussion of that exhibition, and what it tells us about Te Papa in general. Firstly, though, let me give you a quick bit of background on why Te Papa has an exhibition on Gallipoli in the first place. Gallipoli, in Türkiye, was strategically important in WWI as a location protecting the Dardanelles Strait. Allied troops arrived there in 1915, and fought in harsh conditions with terrible losses for eight months. Many of the troops were from British colonial regiments, particularly Australians and New Zealanders. Ultimately the campaign was a failure, and the Allied forces withdrew.

Outside of the Antipodes, Gallipoli is not as well remembered as other campaigns like the Battle of the Somme. But for Australia and New Zealand it marked the start of a growing sense of national identity separate from Britain. These countries felt proud of their soldiers, with a hint of betrayal at having been put in that position by the motherland. They felt the high death tolls keenly. Australia and New Zealand still commemorate WWI on a different day to many countries (25 April vs. 11 November) – a date connected to the Gallipoli campaign. It’s a key moment in New Zealand’s history.

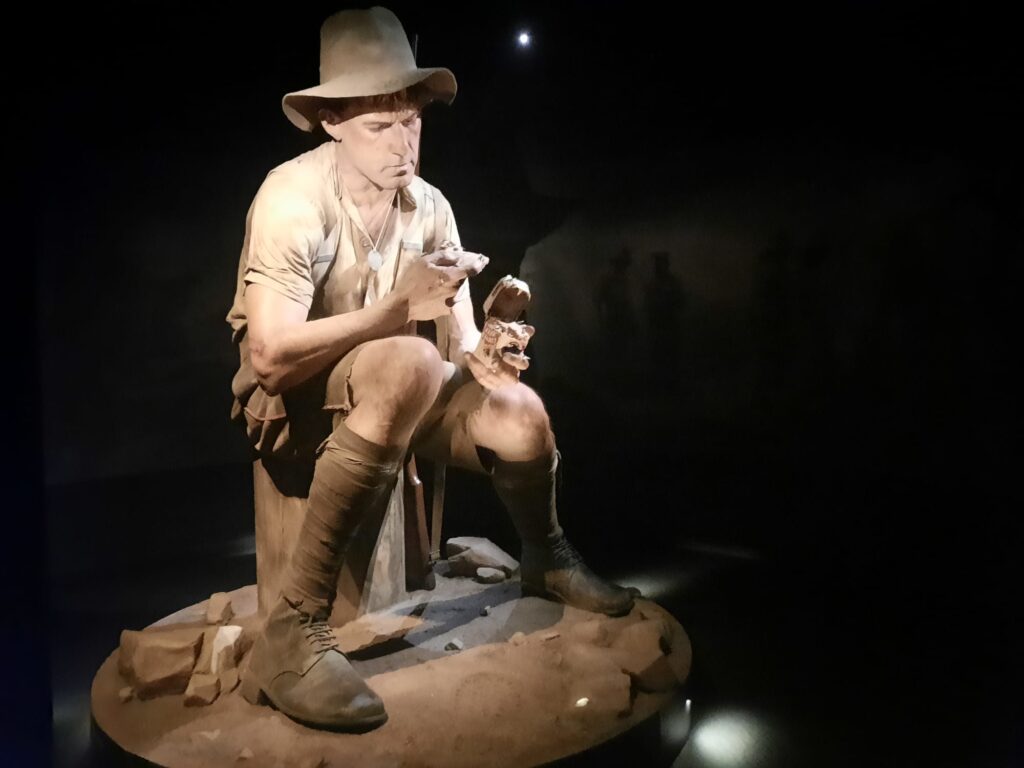

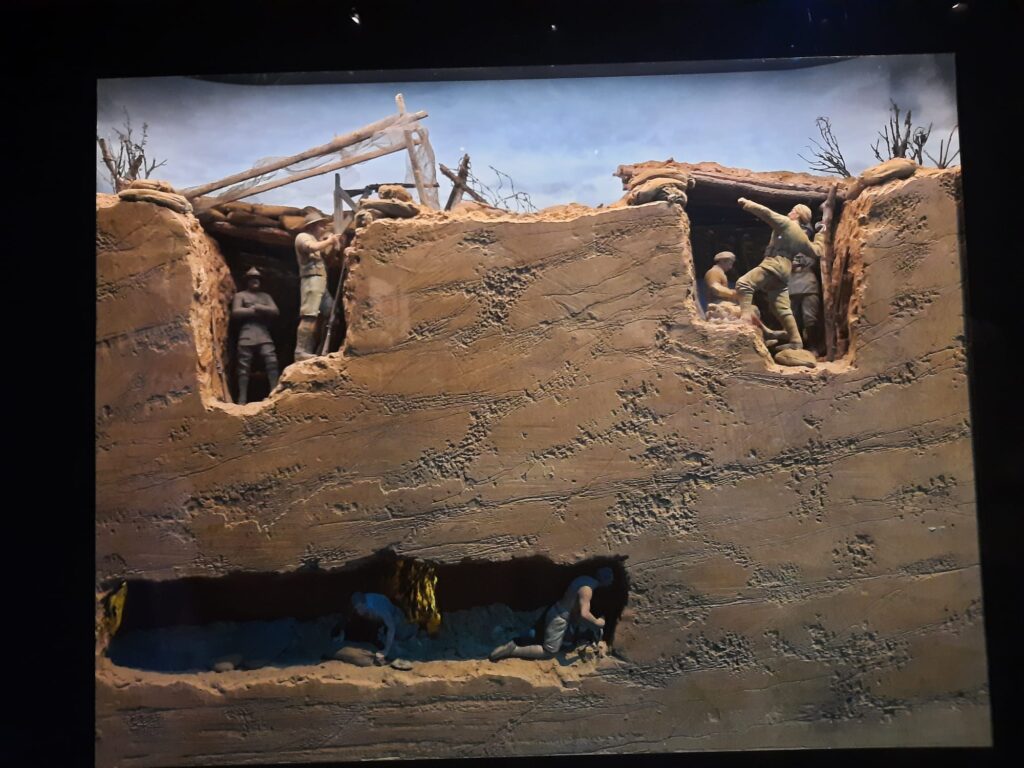

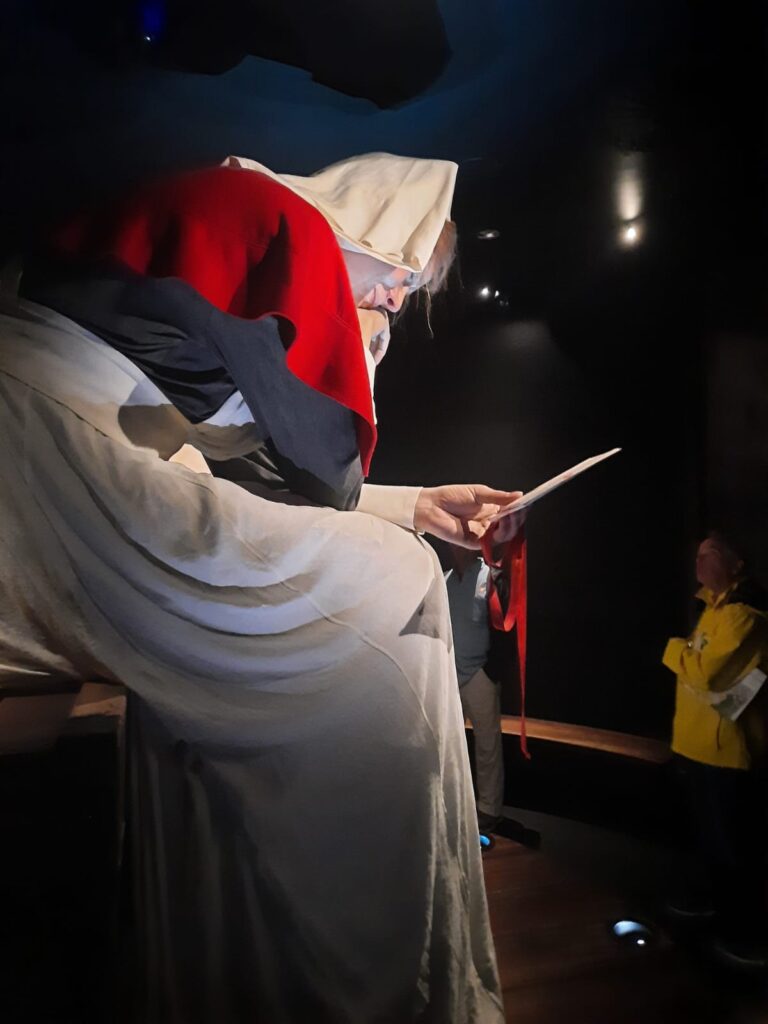

The exhibition Gallipoli: The Scale of our War tells this story, and explains its significance. And it does it in a way which both plays to Wellington’s strengths, and reminds me of some of the early debates around Te Papa and its approach. In terms of playing to strengths, the exhibition is a collaboration between Te Papa and Weta Workshop, the special effects company behind The Lord of the Rings and countless other films and experiences. Weta Workshop spent 24,000 hours creating eight figures that are 2.4 times human scale. These figures are real individuals involved in the Gallipoli campaign, depicted at a key moment.

Te Papa’s Exhibition Approach

And the early debate? When Te Papa first opened (and periodically since then), there were some accusations that it isn’t serious enough. That it’s a ‘sideshow’ or a ‘theme park’. And it doesn’t have the feel of some museums: it’s not every institution who would tackle war through dioramas of oversized humans. I think there are a couple of things driving this particular vein of criticism. Firstly, Te Papa is firmly object-led, and uses objects to open up engaging and interesting stories. The curatorial tone is also accessible, and frequently playful (except where that would be inappropriate). Those who prefer their museums as sombre temples of culture disapprove, it seems.

Going back to the Gallipoli exhibition, I can see both sides. The historic content was well-researched and thorough. As well as the big figures there were other models and dioramas explaining different topics. And yet there was something about the visual presentation which put it almost on the cusp of… sensationalism? Theatricality? Maybe it’s my knowledge of Weta Workshop’s involvement, maybe it was the heavy use of spotlighting and big text. Or maybe it was those enormous figures, captured in a moment of heightened emotion, designed to draw the same from us as viewers. It works: I felt overwhelmed by the horrors of war by the time I exited. But it’s certainly not how every museum would approach it.

New Zealand isn’t every country, though. There’s less formality than in many societies. A conversational tone in a museum setting works quite well here. Te Papa’s bicultural governance model also plays a part. The reflection of mātauranga Māori (Māori system of knowledge and world view, roughly translated) is incompatible with an authoritative curatorial tone privileging a single (Western) point of view.

The Overall Visitor Experience at Te Papa

I was getting a bit museological in that last section, forgive me. I find this a very interesting case study in terms of museums and national museums. But I don’t have enough space here to really get into that, and we also need to finish talking about the experience for visitors to Te Papa.

Those museological bits I was talking about above make, overall, for an engaging visitor experience. The objects on display are diverse and interesting, as are the stories they reveal. The information is accessible, and there is very little here that even the most sullen teenager visitor on a family outing could find boring (unless I underestimate teenagers, which is entirely possible).

The main thing, as in many museum experiences, is focusing in on what you want to see. Unless you’re very dedicated and have a whole day to spare, you won’t see it all. You’ve seen in the images above the bits that we chose. For myself as a former resident and the Urban Geographer as a visitor to Aotearoa New Zealand, they gave us new insights into aspects of this country and the wider Pacific region. They also sparked lively conversation, although the Urban Geographer was not, I thought, suitably impressed by the resident colossal squid.

So if you are visiting for the first time, I suggest taking a look at the map on site or in advance online, and plotting a bit of a route. Please note the art galleries are currently closed: to be honest the art doesn’t feel like the main event at Te Papa anyway so wouldn’t have been my top recommendation. Choose a few topics according to your interests, and don’t forget the outside bush walk experience if you need some fresh air. Te Papa is within easy walking distance from most Wellington sights so can be combined with a variety of different itineraries.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.