Dr Johnson’s House, London

A rare surviving Restoration-era house in the City of London, Dr Johnson’s House tells the story of a man whose influence on the English language continues to the present day.

Samuel Johnson, an Introduction

Today’s post is about Dr Johnson’s House, a small museum in the City of London. But who, first of all, is Dr. Johnson? I’m sure there have been a lot of Dr. Johnsons, but the one we’re talking about here is Samuel Johnson. Born in 1709 in Lichfield, Staffordshire, he was born to a bookseller father Michael and mother Sarah. The family were not wealthy: the arrival of a second son three years later made it tougher to make ends meet. Neither was young Samuel blessed with health. He was a sickly infant, and suffered with scrofula as a youth. We’ve talked about scrofula (or “the King’s Evil”) before on the blog: people believed a monarch’s touch could cure it. But although Samuel duly received a touch and an amulet from Queen Anne in 1712, it didn’t cure the affliction.

So anyway, he was born, had a brother, and indifferent health. He did show signs of intelligence from an early age, however. His schooling was a little informal, as schooling mostly was at that time. Young Samuel’s ran the gamut from receiving education from a retired shoemaker, to attending grammar schools. The family’s finances hadn’t picked up, but an inheritance from a relative made it possible for him to attend Pembroke College, Oxford. For a time, anyway: eventually he had to leave when he fell behind on fees. He received honorary degrees later in life.

Another thing to know about Samuel Johnson is that he probably had Tourette’s syndrome. But that wasn’t formally described until 1885. The descriptions of gestures, tics and grimaces certainly points to it, however. And those distracting tics, combined with a lack of degree, hindered Johnson’s career prospects. A marriage to a lady of some means 20 years his senior in 1735 did provide a cushion, however. Elizabeth, or ‘Tetty’, funded some of Johnson’s endeavours, including as master of a not very profitable school with only three students, one of whom, David Garrick, later found fame as an actor.

Johnson in London and the Dictionary Project

In 1737, Johnson and Garrick went off to London together. It seems slightly an odd thing to do, but there you go. At some point he did start to feel uncomfortable living off his wife’s money, maybe that was part of the reason for seeking new fortunes in the big smoke. He did bring her to London about eight months later, though. In London Johnson did various jobs, including some writing, and roamed the streets with similarly penniless friends.

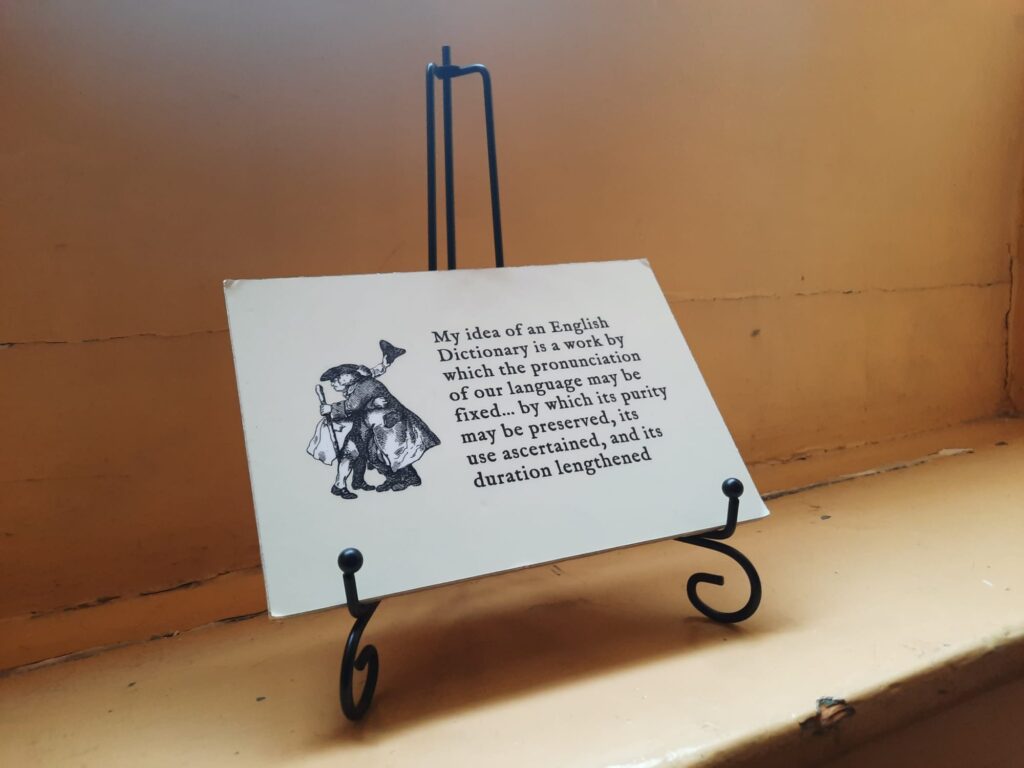

In 1746, however, an important opportunity arose. A group of publishers approached Johnson and asked him to produce a dictionary of the English language. There are some few examples of dictionaries going back millennia, and some Early Modern ones, but the idea had really started to take off in the Enlightenment. So Johnson’s dictionary wasn’t to be the first English dictionary, but it would be the most comprehensive to date and one of the most influential ever.

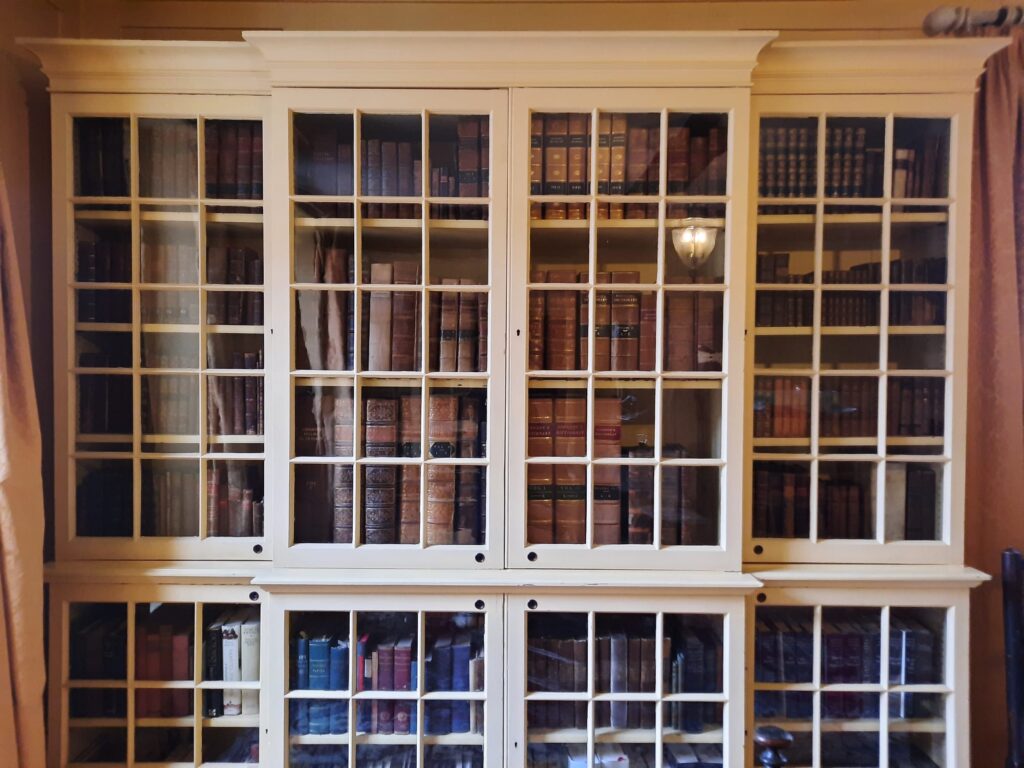

And it really was an immense undertaking. Johnson thought it would take him three years, but it took eight. Although to be fair the comparable project in the French language took 40 years with considerably more hands on deck. Johnson did have assistants: a dictionary is easy(ish) to maintain once it exists, but to create one you have to go find words and write their definitions. Johnson did this (great task for the son of a bookseller) and his assistants did the copying and mechanical work. He had a lot of books in his own collection, and borrowed as much as he could. He had a reputation for returning them in much worse condition than he borrowed them in, however.

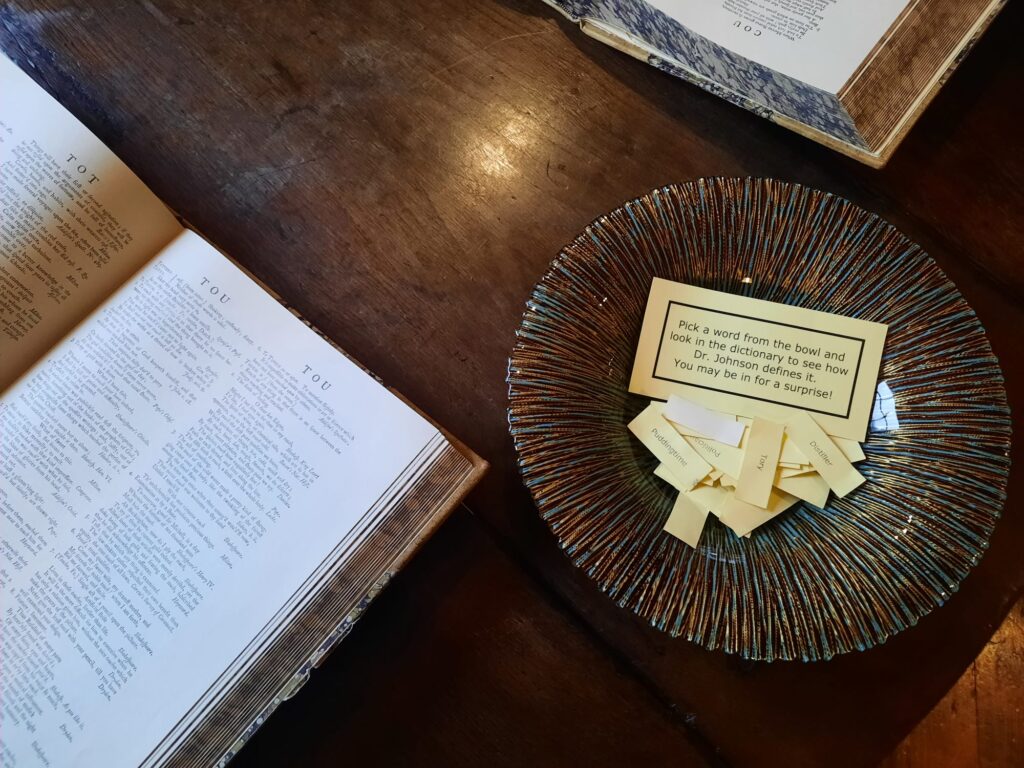

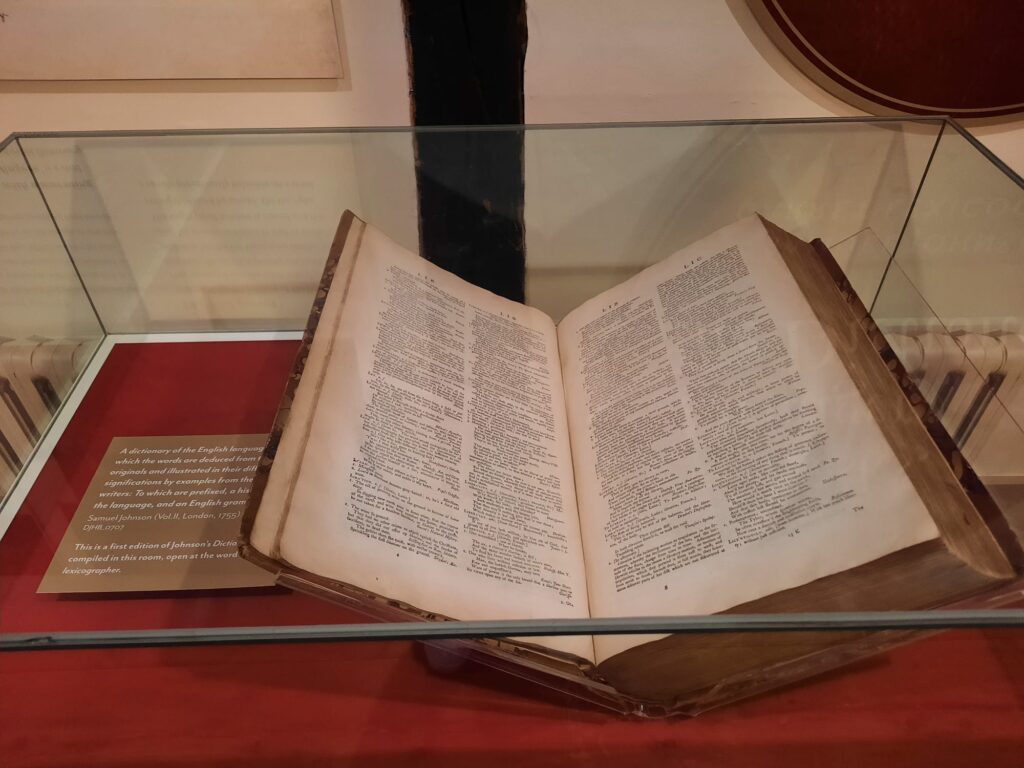

A Dictionary of the English Language was published in 1755 in two volumes. It was an immense undertaking, and an innovative one. One idea introduced by Johnson was to illustrate the meaning of words using literary quotes, eg. from Shakespeare. As Johnson was under contract to produce the dictionary, he didn’t profit from subsequent sales. But he did have an immense impact. Johnson continued to juggle writing and money troubles in subsequent years, and mourned his wife’s death in 1752. In 1762 King George III awarded him a modest pension, which helped ease his financial worries. Johnson died in 1784 and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

Dr Johnson’s House

What about this house, then? From the description of Johnson’s life above, you will not be surprised when I tell you he rented his London homes, and moved around a lot. About 18 homes in London. Of those 18, this is the only one which survives. And, even better, this is where Johnson lived while working on his Dictionary, from 1748 to 1759. It’s in an alley near Fleet Street: conveniently close to printers and publishers.

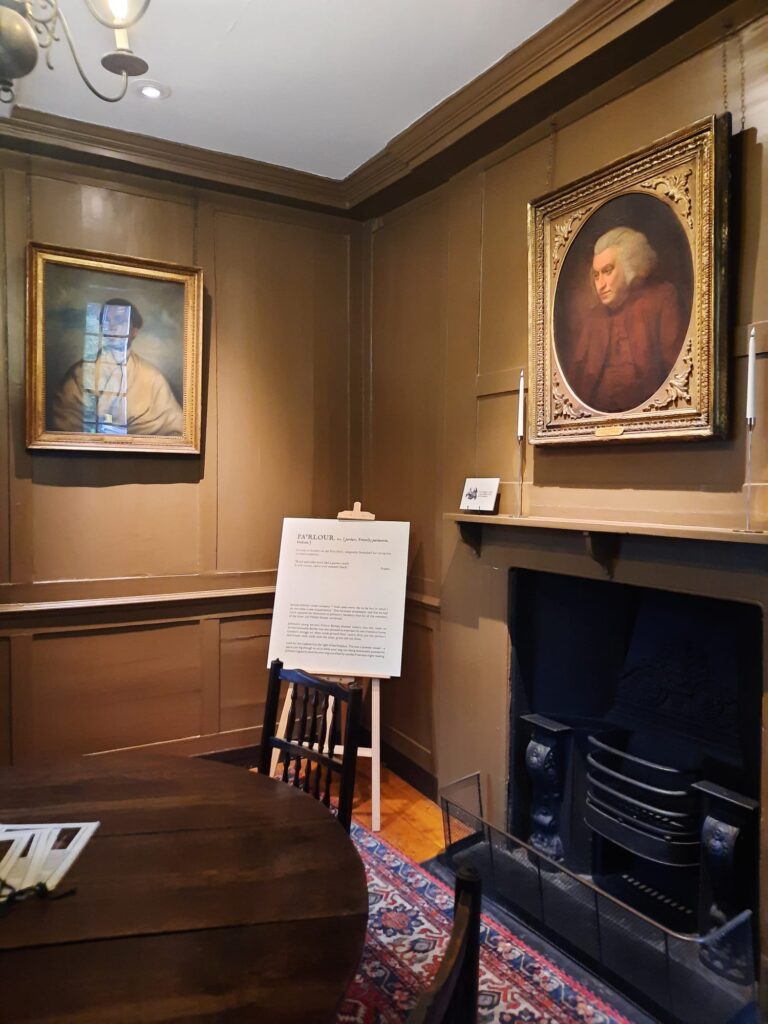

It is a house museum in the model of Hogarth’s House, Benjamin Franklin House and others we’ve seen, in which ownership has not been continuous. After Johnson lived here, it was variously a print shop, hotel and storehouse. By 1911 it was pretty derelict. It was then that politician and newspaper magnate Cecil Harmsworth purchased and restored the property. Luckily, many of its original (late 17th century) features survived. This includes panelling, floorboards, door handles, coal holes, and more. A similarity with Benjamin Franklin House is being able to see how people secured their homes, here including a heavy chain and spiked iron bar.

To really set up a house museum, though, you need something in it. Dr Johnson’s House today has a fair amount of period furniture. And it also has a number of items associated with the man himself, or his friends and associates. Some were purchased directly by Lord Harmsworth and his wife, like a chest belonging to David Garrick. Others have more convoluted histories.

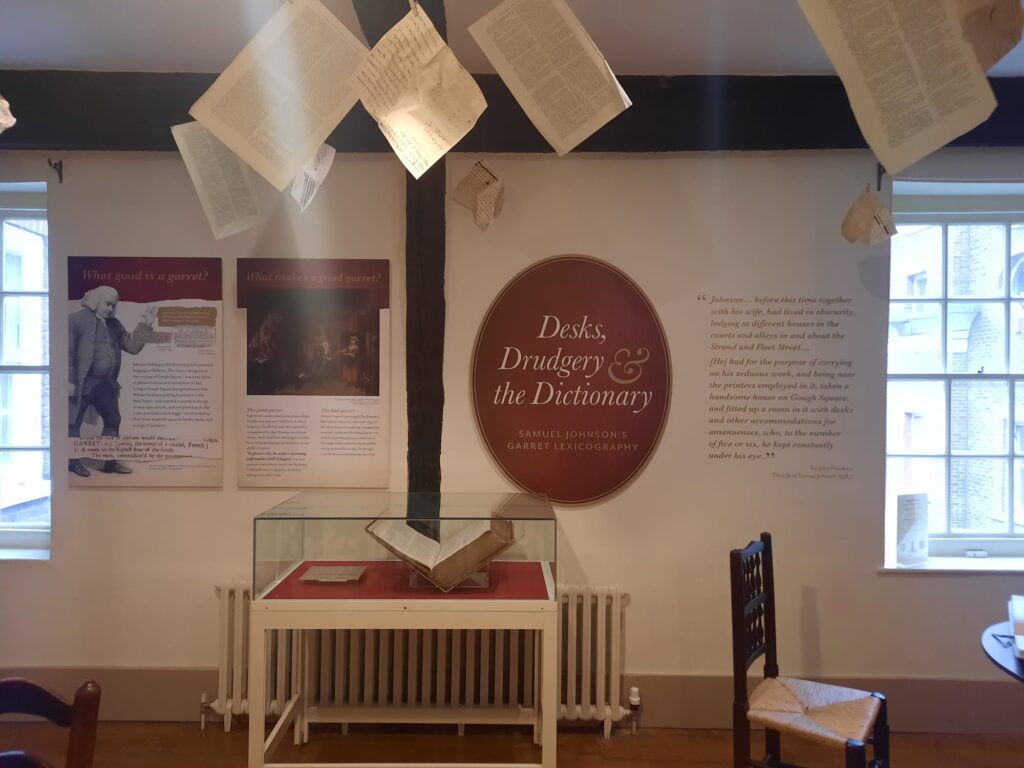

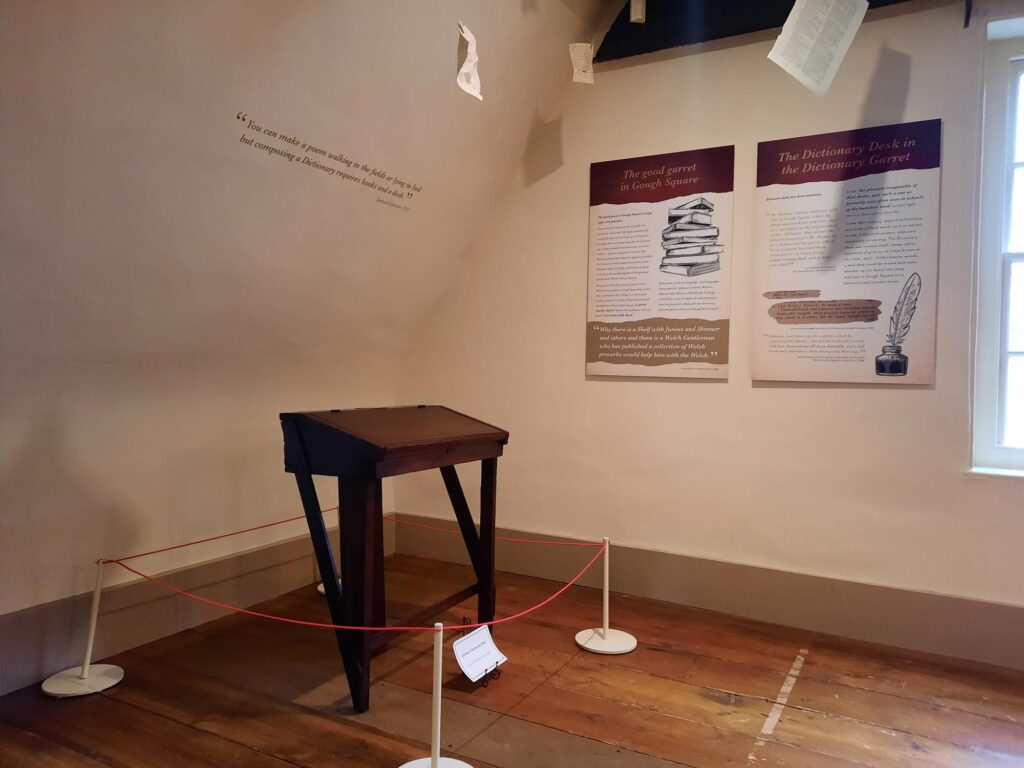

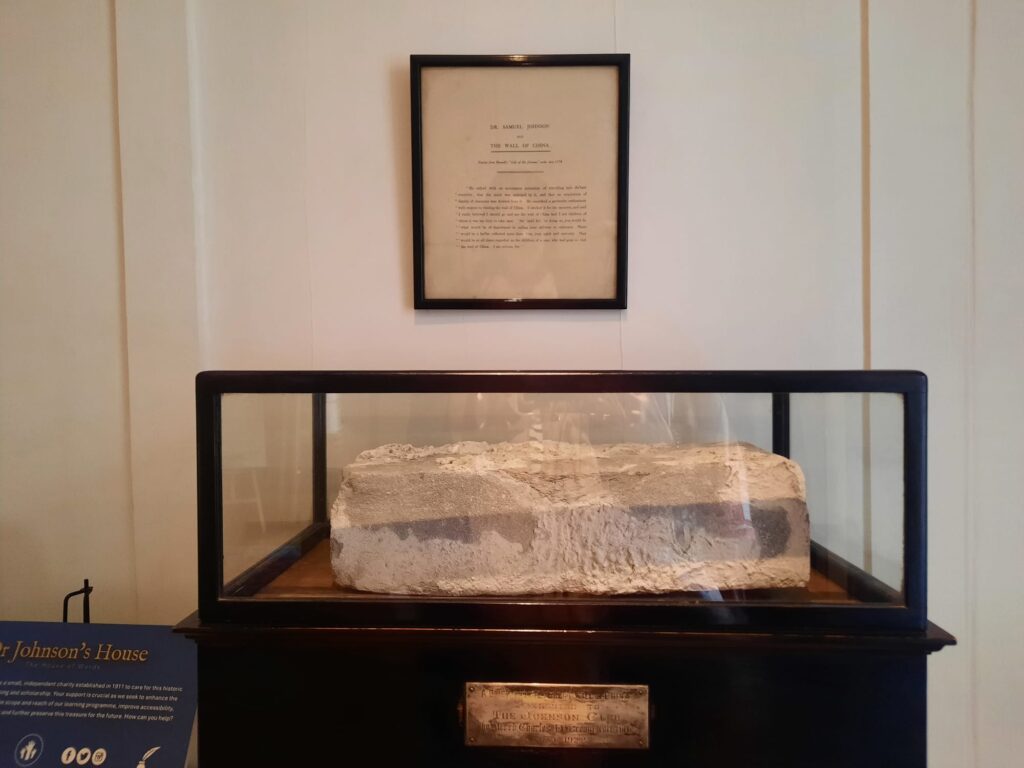

Although it’s a loan rather than the permanent collection, I’m thinking particularly of what was supposedly Johnson’s desk and used in the preparation of the dictionary. It ‘reappeared’ in the 19th century in the possession of Johnson’s goddaughter. Coincidentally she was much in need of funds, as she was then living in squalor in Deptford. There were many influential supporters and subscribers in favour of securing the future of this seemingly important relic. In the end it took up residence in Pembroke College, Oxford. It’s back at the moment as part of a temporary exhibition.

Visiting Dr Johnson’s House

The visitor experience at Dr Johnson’s House is rather a pleasant one. This is a fairly niche subject, after all, so not a place you’re likely to be overrun by tourists new to the city. Walking into Gough Square, although the museum is the last remaining building from the original development, you get a little of the feeling of how the City of London used to be. You then walk up some stairs and enter the museum through a side door. As little as possible of the house is taken up by museum administration, but this is where the shop and ticket counter is found.

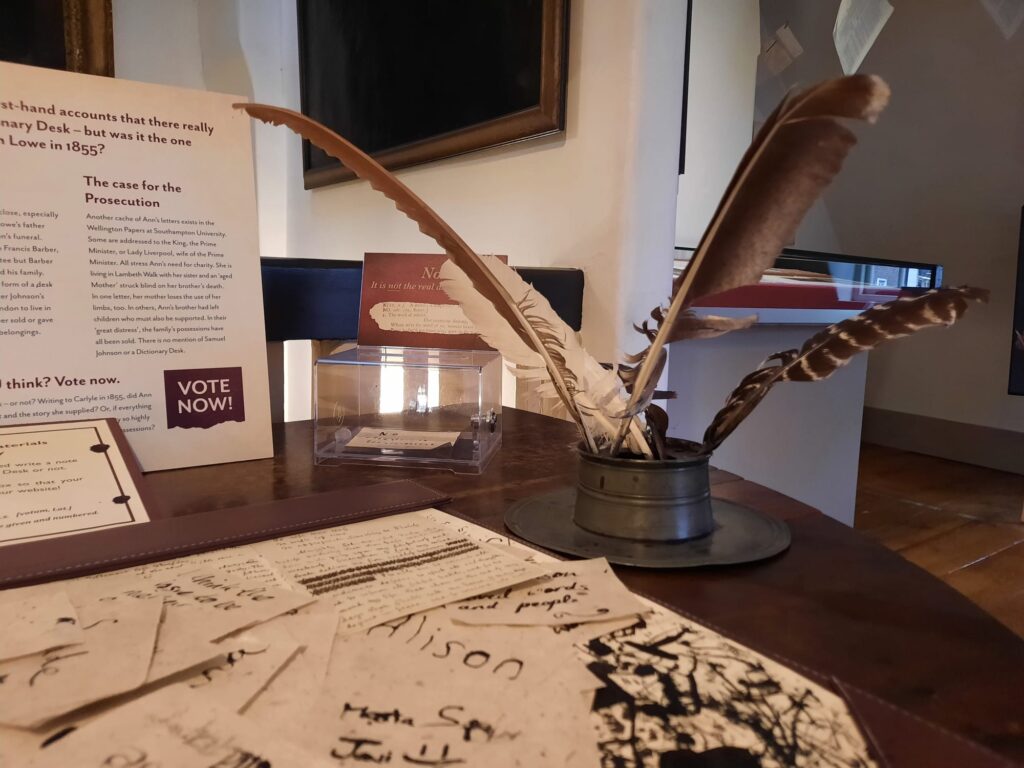

It doesn’t particularly matter whether you start at the bottom and work your way up, or vice versa. I started at the top. The garret is where Johnson and his associates worked on the dictionary. It’s here you can learn the arguments for and against the legitimacy of the ‘dictionary desk’, and understand how Johnson undertook this massive project. There are some simple but effective ways to make things more interactive, which I appreciated.

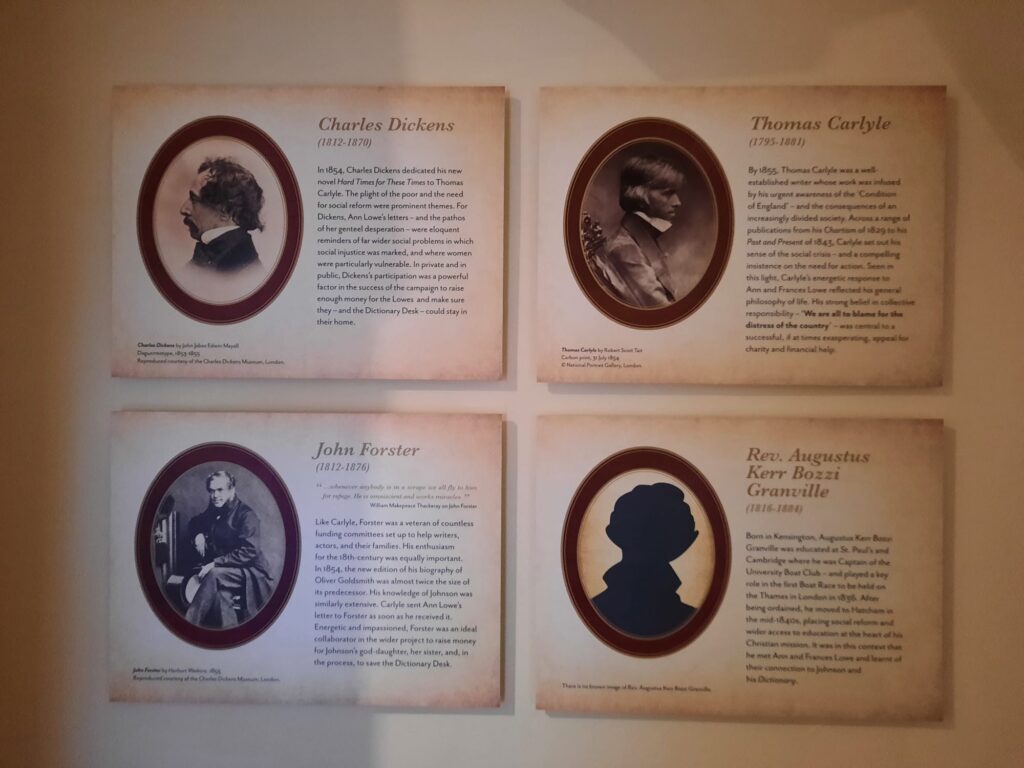

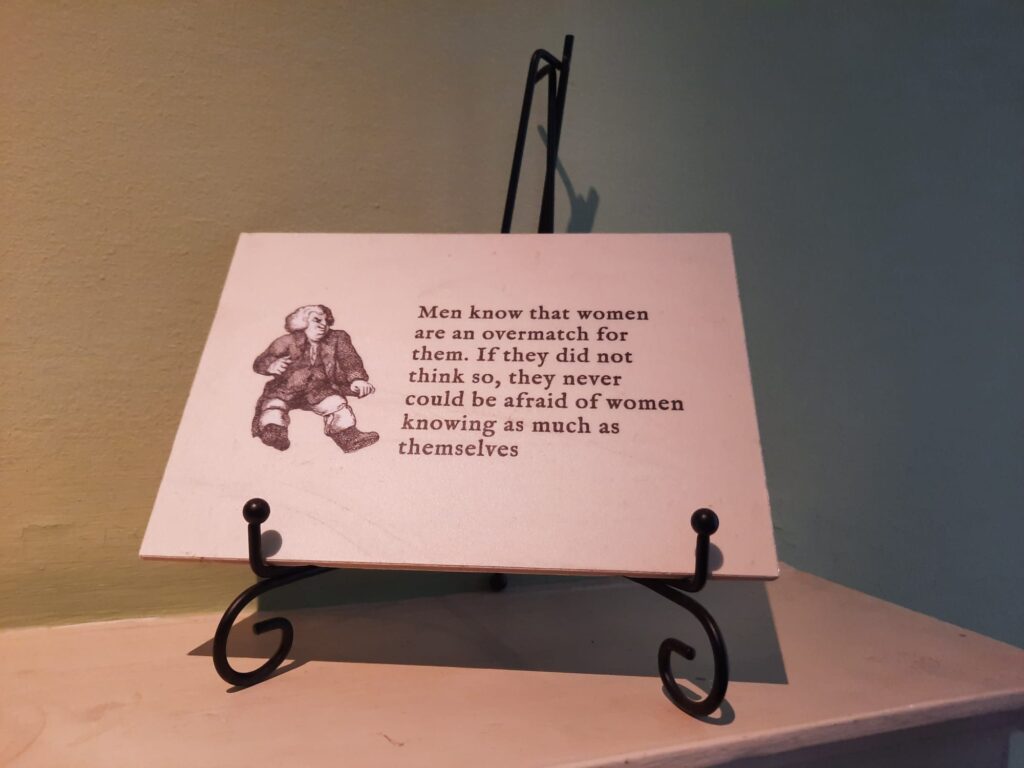

Heading downstairs, the content was more about Johnson’s life and circle, and the 18th century context. We meet characters like his blind lodger and housekeeper Anna Williams, and Black servant and eventual residual heir Francis Barber. The period furniture and assorted items linked to Johnson and his circle are enough to get a feel for life here when Johnson rented the property.

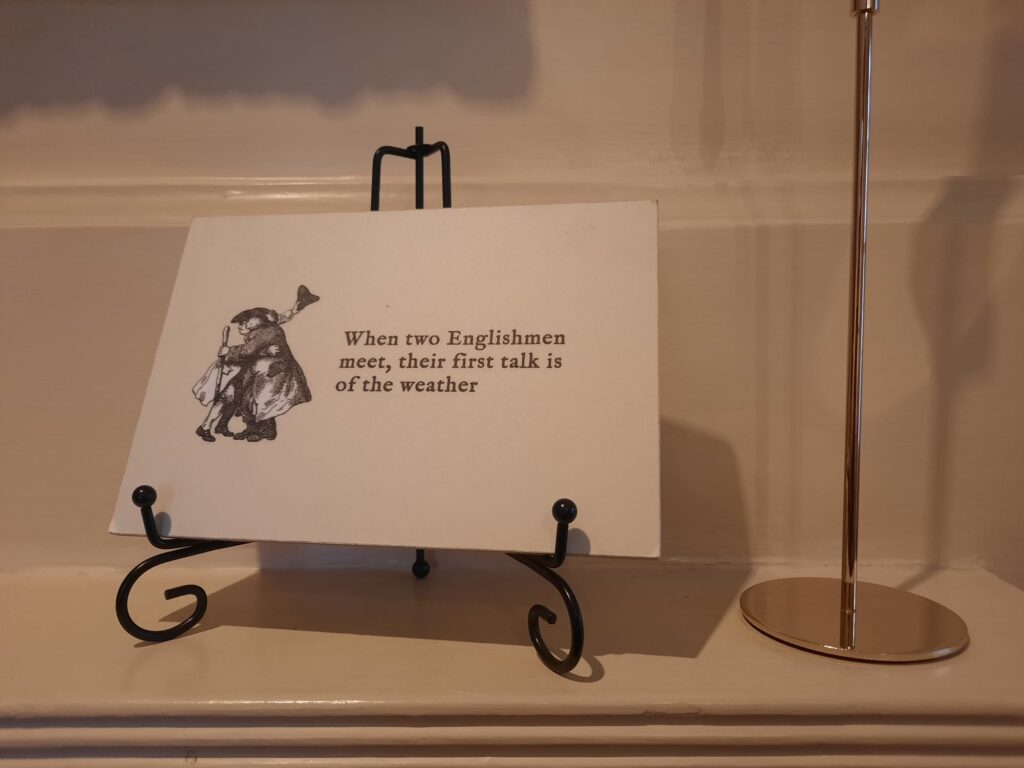

I recommend the museum for those who enjoy history, literary topics, aphorisms, or peaceful, specialised museums. There’s a fair amount of reading: this is perhaps appropriate. I learned about a topic I only knew peripherally. And I enjoyed getting inside a building I’ve only passed by before. “When a man is tired of London, he is tired of life”: according to Johnson, then, I’m doing alright.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.