Groundbreakers: Grace Joel, Frances Hodgkins and the new art of Ōtepoti – Dunedin Public Art Gallery

An exhibition at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery gives insight into the city’s Groundbreakers, a pair of pioneering female artists and the city’s vibrant art community.

An Exhibition Under the Spotlight

My last post was an introduction to the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Not an introduction for me – I actually worked there for a brief moment once upon a time. But an introduction for my dear readers of this normally London-based blog. I like to take you all with me when I travel further afield, including trips to my far-off home town.

The Dunedin Public Art Gallery is a versatile space. As well as showcasing the gallery’s permanent collection – the first public art collection in Aotearoa New Zealand – they normally have a few different temporary exhibitions on at once. This is a great chance for local residents and visitors alike to encounter a range of artists and topics, almost always for free. We looked at a few of the temporary exhibitions in my last post. But there was one that I wanted to look at in a bit more detail, because of what it says about art and artists in early Dunedin.

That exhibition is Groundbreakers: Grace Joel, Frances Hodgkins and the new art of Ōtepoti. Ōtepoti is, of course, the Māori name for Dunedin.* And the name Hodgkins may ring a bell. In my last post I mentioned a William Hodgkins, an immigrant from Liverpool by way of Australia, who was the driving force behind Dunedin’s artistic community and the formation of what is today the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, in the late 19th century. Let’s take a closer look now at this community, and its famous daughters.

*The exhibition favours Ōtepoti. I’ve leaned towards Dunedin, to avoid confusion for my general reading population as the name that crops up most frequently in the period under discussion. But generally I love the move towards Māori or bilingual placenames in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Art in 19th Century Ōtepoti / Dunedin

We love a bit of context here on the Salterton Arts Review. And so we’re going to spend a bit of time on the subject of art in Dunedin in the 19th century. Starting with a disclaimer: we’re talking here exclusively about how European settlers transplanted art in a Western context to the city, and how it began to evolve from an amateur pursuit to a professional vocation. Not any Māori art forms, which long pre-dated colonial artists but took a lot longer to make their presence felt in the mainstream New Zealand artistic canon. That might be a subject for another day.

But I think this is already a key point. We’re talking about art in the context of a settler society within the British Empire. And Dunedin was a city developing quickly in a British mould in the 19th century. From European settlement in the 1840s (see some discussion of pre-Dunedin Ōtepoti here), Dunedin moved quickly to a lot of Aotearoa New Zealand firsts. First university in 1869. First public girls’ high school in 1871. And so on. Powered by the influx of people and money as the gateway to the 1860s gold rush in Central Otago, the people of Dunedin set about recreating British society in an entirely different geographical and cultural context. This included art.

Far from the art market and clientele of “Home” (as many New Zealanders referred to Britain well into the 20th century), though, things looked a little bit different. Early artists in New Zealand were mostly amateurs, for a start. The main cities or regions each had their own Art Society (the Otago Art Society was formed in 1876), with artists frequently exhibiting in multiple exhibitions. As well as these societies artists formed other groupings within towns and cities. Dunedin, for example, had by the late 19th century an Art Club which met in the homes of members, and an Easel Club which developed in reaction against the city’s art establishment. Women seem to have part of all these organisations. Although women still faced many barriers to becoming professional artists, artistic accomplishment was expected of young women of a certain social standing in New Zealand as at “Home”.

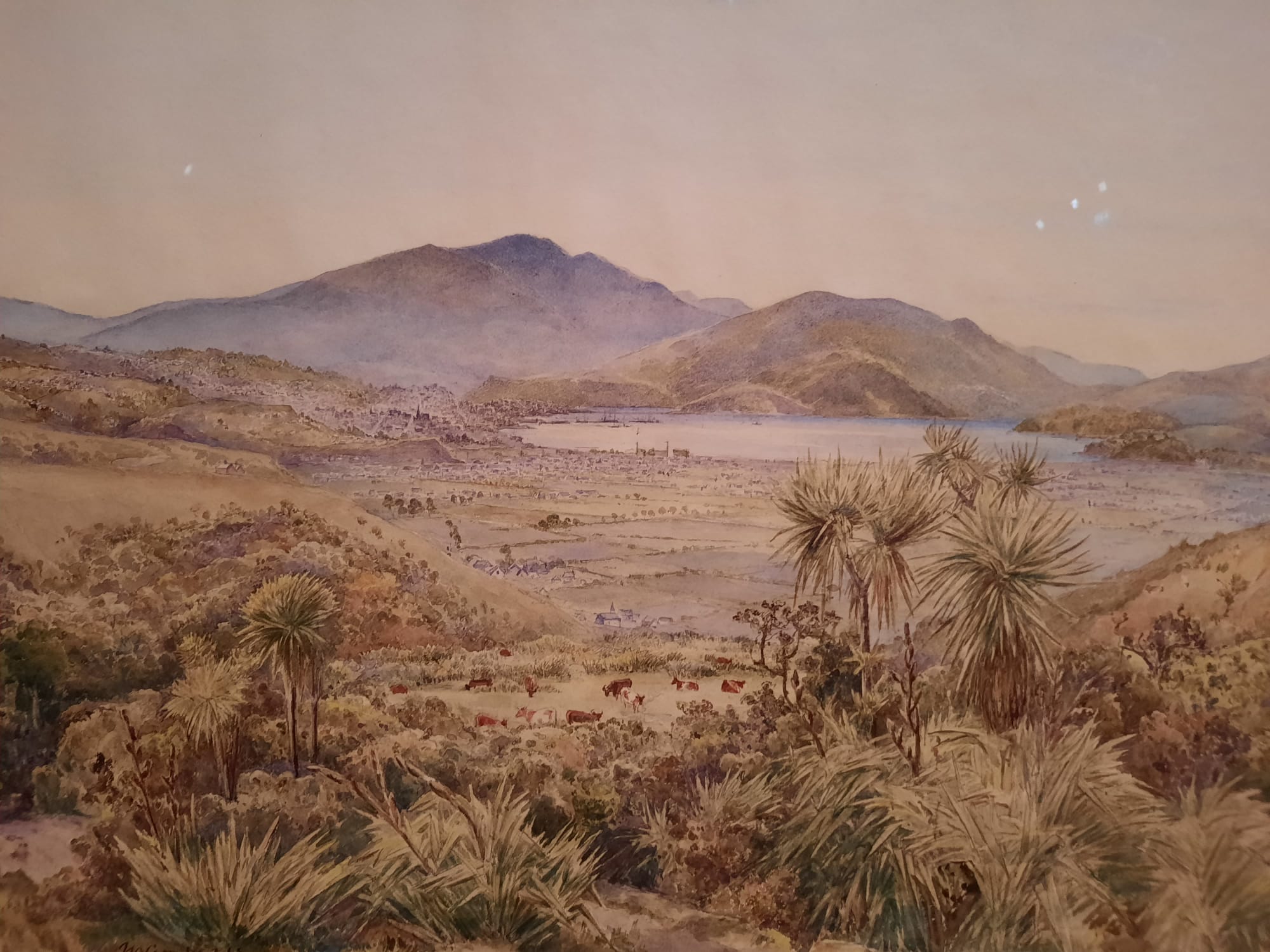

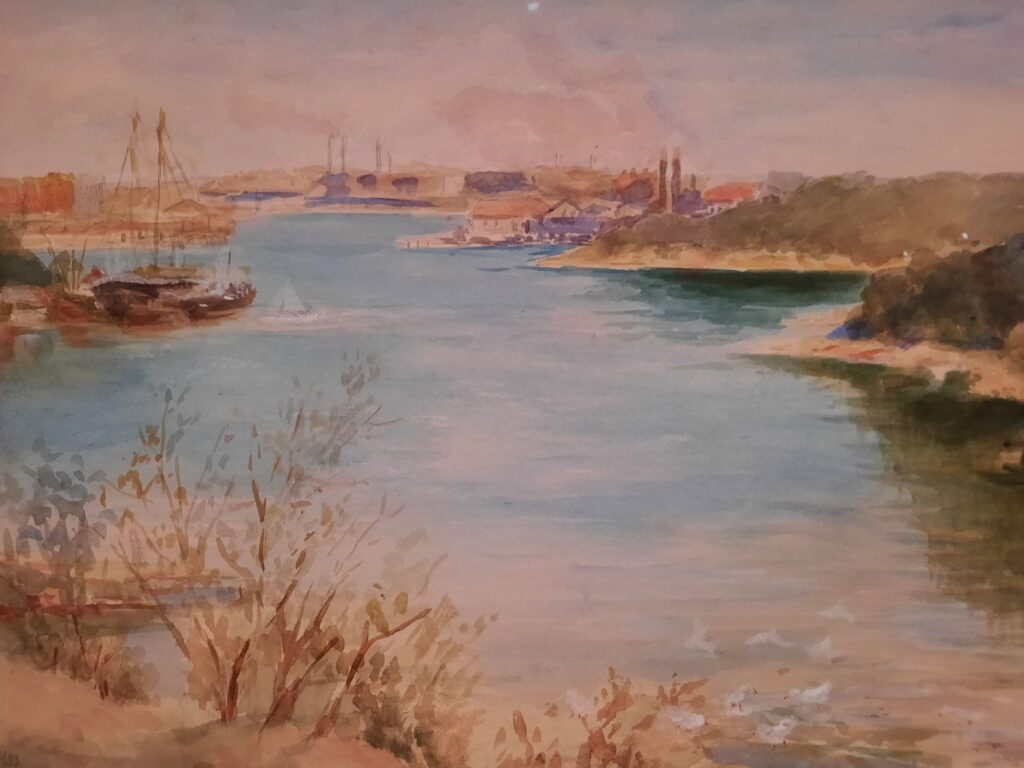

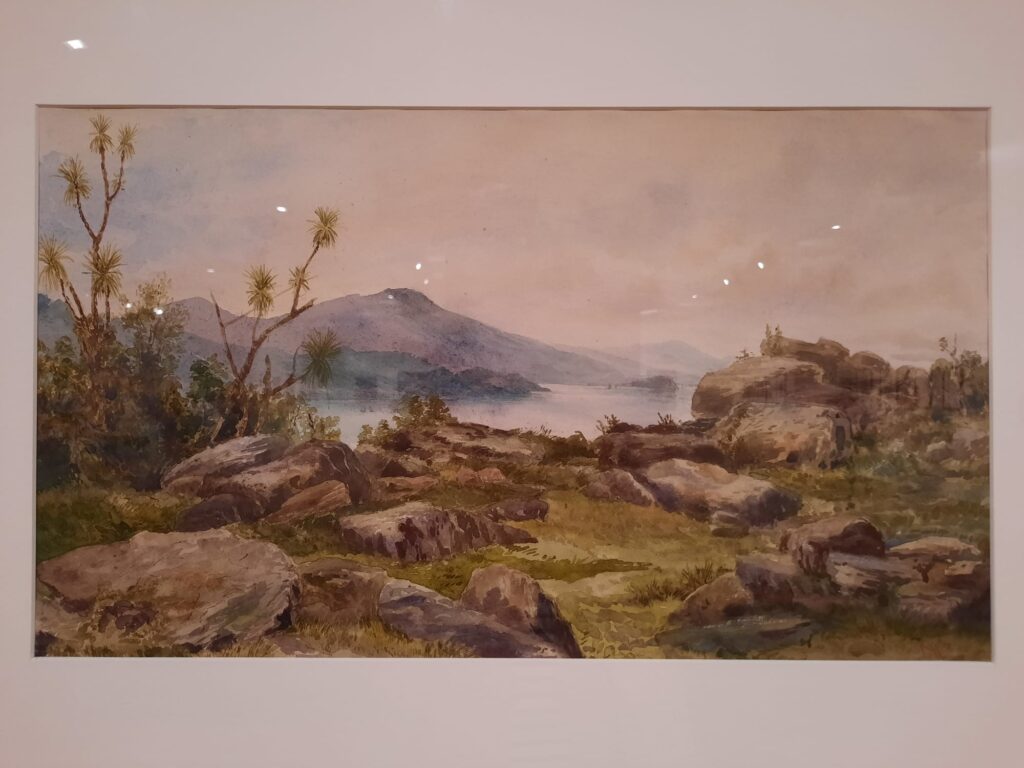

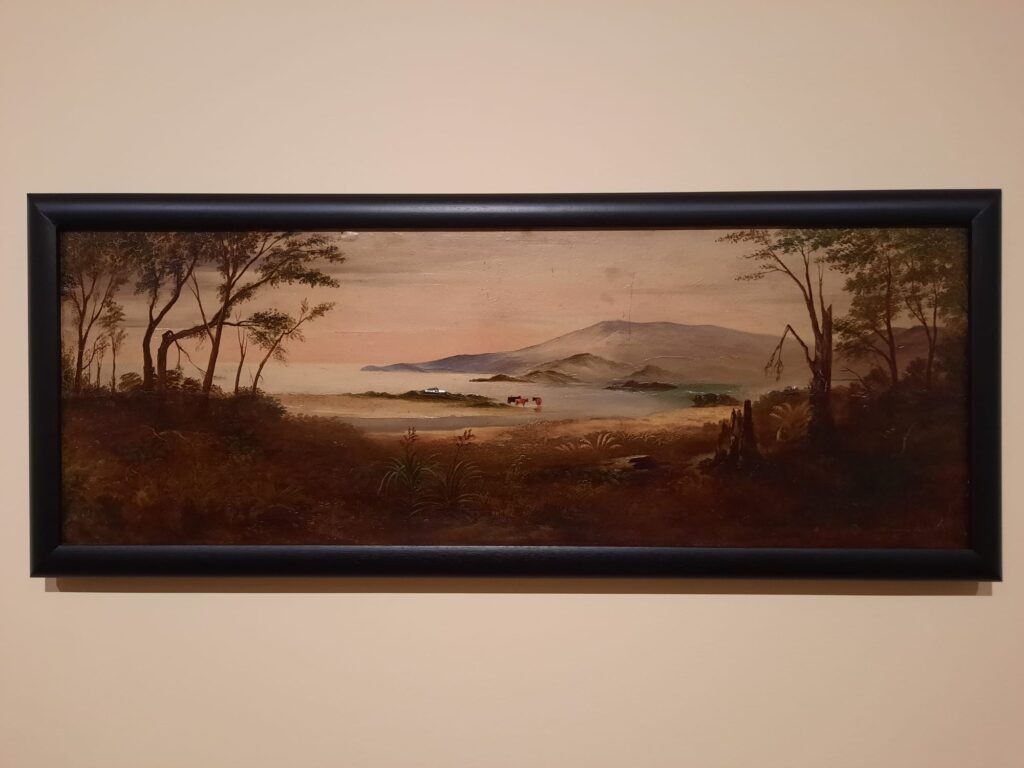

The actual art itself – what was being depicted and how – also went on a journey in this colonial context. Early amateur artists brought with them Western, particularly British, ways of depicting subjects. New Zealand’s stunning landscapes were a common theme. But these were commonly filtered through a lens of topographical depictions or British landscape tradition. Taking again the example of Dunedin, things began to shift in the 1880s and 1890s. There was a growing artistic community, thanks in no small part to the dedication of William Hodgkins. And an important injection of new ideas and styles came from new arrivals – artists who visited or settled in the city. Girolamo Pieri Nerli (1863-1926), for instance, James Mclachlan Nairn (1859-1904), or Petrus van der Velden (1837-1913). Things were getting more interesting.

The Groundbreakers Emerge

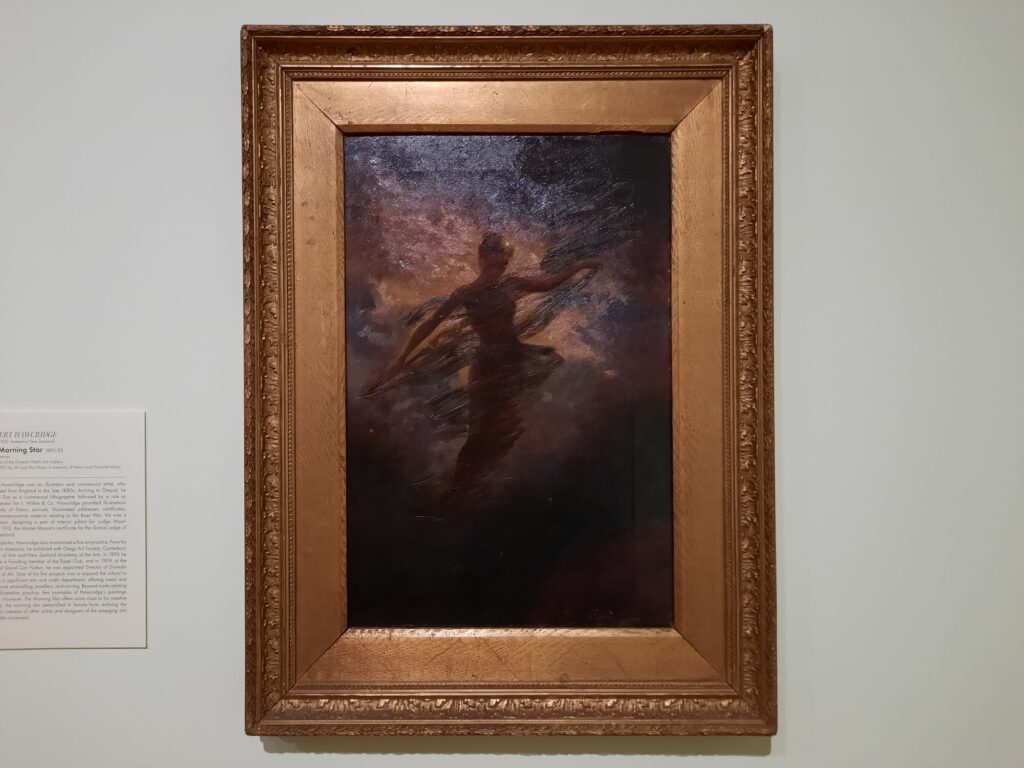

That was a very quick overview of a very interesting and nuanced topic. If you want to do any further reading, you could make a start here, or here. But we are going to circle back now to the exhibition under discussion. The previous section described an art scene in transition. A healthy community of passionate amateurs, benefiting from new ideas arriving from abroad. And it’s this community which Groundbreakers explores. Because we see art not just by Joel and Hodgkins, but also by William Hodgkins, Jenny Wimperis, Isabel Field, Girolamo Nerli, Nellie Hutton and more.

But who are Joel and Hodgkins? Let’s start with Hodgkins, as we’ve met her father already. Frances Hodgkins was born in Dunedin in 1868. Her father encouraged both her and her sister in their artistic talents. Frances had private classes as well as attending the Dunedin School of Art. She began exhibiting works in the 1890s and ultimately found success as a professional artist. She left for Europe in 1901, studying and painting in a number of countries before ultimately settling in England. Hodgkins was a key figure in British Modernism, and her work is in collections including the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Auckland Art Gallery, Tate, British Council, Leeds Art Gallery and more. She died in 1947.

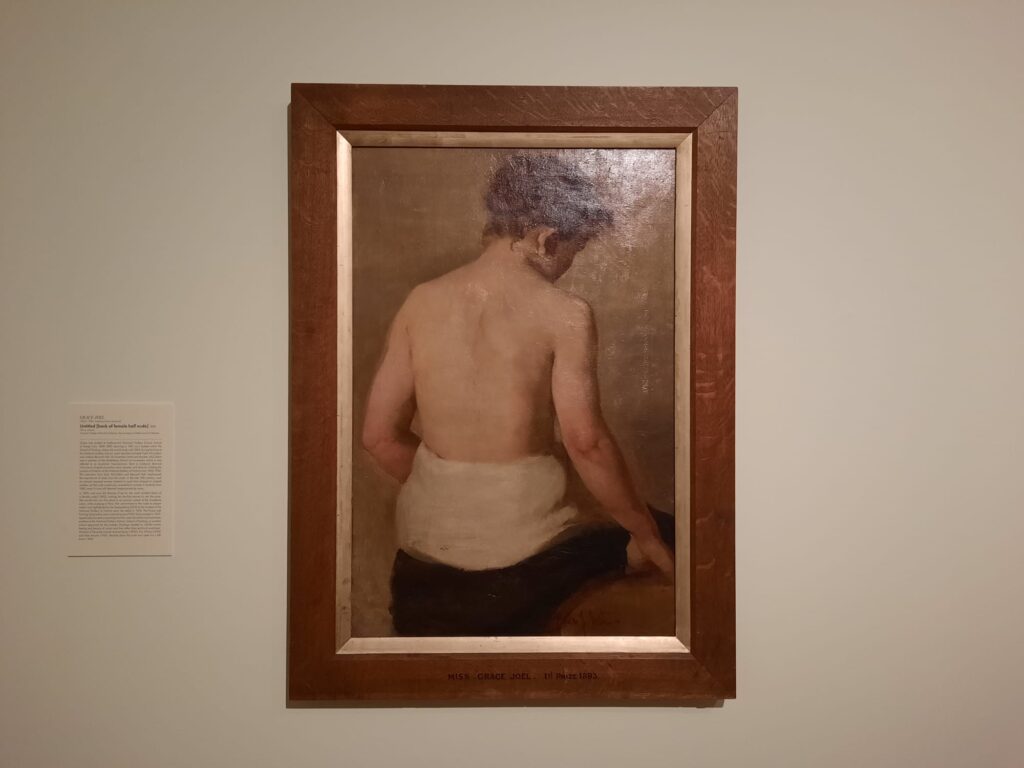

Grace Joel was also born in Dunedin, in 1865. Her English-born parents became prominent members of Dunedin’s Jewish community. Joel attended Otago Girls’ High School (that ‘first’ I mentioned above) and became a member of the Otago Art Society in 1886. She left for Melbourne in 1888 to attend the National Gallery School. After two periods of study (1888-89 and 1891-94) she returned to settle in Dunedin once more. Like Hodgkins, however, Joel ultimately ended up in Europe. She went for a first time in 1899, traveling and working in the UK, France and the Netherlands. She only returned briefly to New Zealand in 1906, and died in 1924.

Our groundbreakers have very similar trajectories, then. Young women who set out from an early age to establish careers as artists. Early talents nurtured within Dunedin’s art scene, before professional training. Honing skills by broadening their horizons and education in Europe. And ultimately settling there. A great advertisement for Dunedin’s art scene, if ever there was one!

Groundbreakers: Grace Joel, Frances Hodgkins and the new art of Ōtepoti

The one thing we haven’t considered very much so far is the exhibition itself. Let’s remedy that now. Groundbreakers is a fairly simple affair. It takes up a couple of upstairs rooms at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Many works are from the gallery’s own collection, or the nearby Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena. Others are loans from further afield, including an important painting of Joel’s from the University of Melbourne Art Collection.

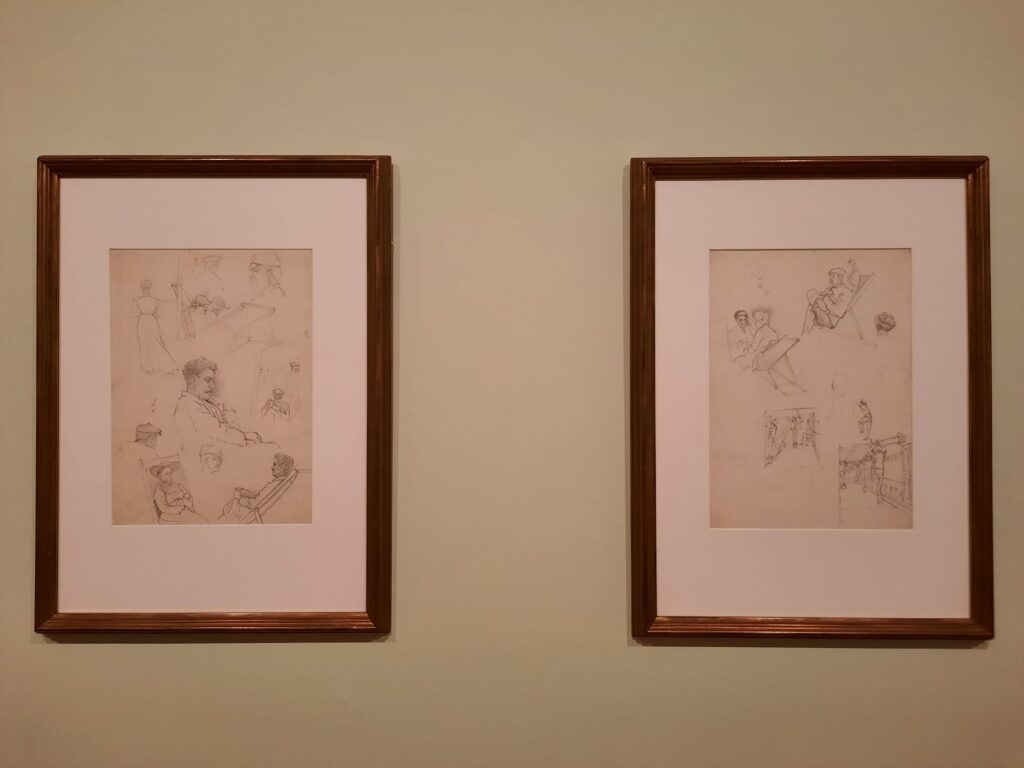

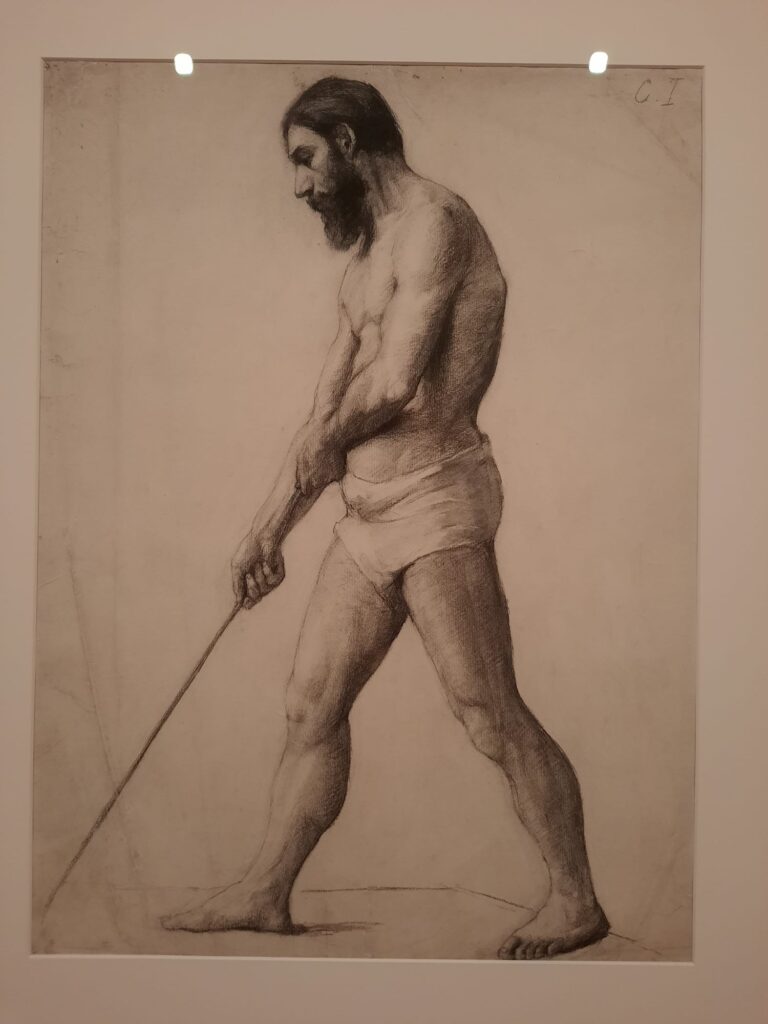

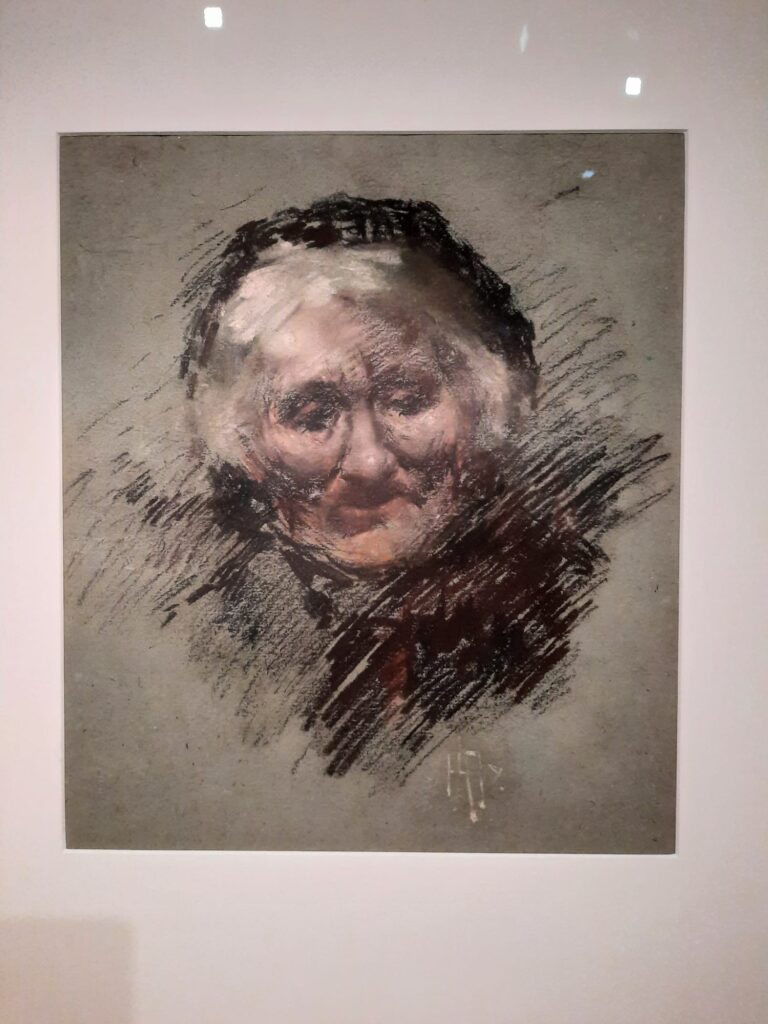

But as I said above, it’s not just works by Joel and Hodgkins. What this exhibition does very well is to place these two artists within an artistic context. We get a very good sense of that community and transition I described above. There are a few traditional landscape paintings to begin with. A number of works that are clearly copies or drawings from life: the hallmarks of a classic art education. And then finished works, showing first the influences of those artists new to Dunedin, and later the broadening of Joel and Hodgkins’ skills as they furthered their careers abroad. It’s fascinating to see how they were similar to and differed from their peers.

I have a confession to make at this point. I liked the works on paper, but didn’t like the oil paintings so much. Not all the works on paper – some of the drawings are clearly student work and nothing out of the ordinary. But there are a lot of nice watercolours and sketches on display. The oils, however, I found a bit… dull.

I don’t quite know what to extrapolate from this, however. Is it that there is something in those colonial, Romantic landscapes that speaks to me, and this is all about my expectations of the art vs. really seeing what’s there? Could be. But I really liked some of the non-landscape works on paper as well, like this or this. Or maybe the new techniques these artists were learning lent themselves better to one medium or another? Could also be that. Sometimes it’s also how galleries conserve their paintings, and a good varnish removal makes all the difference. But I certainly preferred one group of works to the other.

What I really liked about this exhibition was the way it brought these artists and their community back to life. Growing up in Dunedin, Frances Hodgkins is a name you hear a lot. Grace Joel has been overlooked in comparison. But focusing on one star artist (or two) can be to the detriment of understanding where they came from. Groundbreakers breathes life back into what was a very interesting artistic setting in 19th century Dunedin. Learning some of those other early names is also important. Seeing how many other women were part of these circles, for instance, makes it a little easier to see how young Frances and Grace had the confidence to set their sights on professional careers as artists. And who knows – maybe spotlighting “the new art of Ōtepoti” in this way will inspire other aspiring artists to dream big, too.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Groundbreakers: Grace Joel, Frances Hodgkins and the New Art of Ōtepoti on until 27 April 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.