Kirkaldy’s Testing Works, London

Just a stone’s throw from Tate Modern, Kirkaldy’s Testing Works speaks to Southwark’s industrial past and the ingenuity and single-mindedness of one man, David Kirkaldy.

Another ‘New Museum’ in London

One thing I love about London is how much of it I still have to see. I’ve lived here about 15 years now. And yet I have a list of museums and galleries to visit that only ever seems to get longer. In 2024 I finally managed to see two which have been on there for a few years now. First the Bank of England Museum, and now Kirkaldy’s Testing Works. What is perhaps surprising is that I haven’t managed before to get to a museum that is only about two minutes’ walk from Tate Modern. Although, to be fair to myself, Kirkaldy’s Testing Works has much more limited opening hours. More on the practicalities in due course.

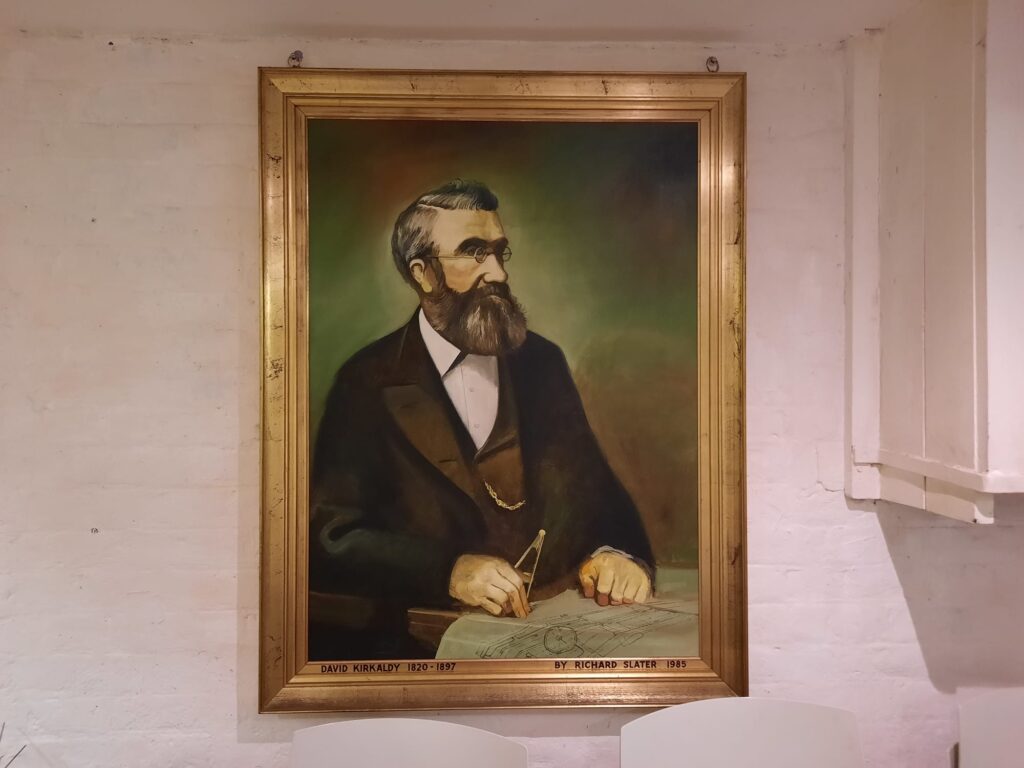

Let’s start, perhaps, by finding out more about the Kirkaldy for whom today’s museum is named. David Kirkaldy. Born in 1820 in Dundee, he only started the apprenticeship that put him on his chosen career path at 23. Pretty late in those days as apprenticeships tended to be a seven year term. This apprenticeship was at Napier’s Vulcan Shipyard in Glasgow. A meticulous eye for detail helped get him a promotion to chief draughtsman and calculator. He had a talent for drawing as well as record-keeping: in 1861 his drawing of RMS Persia was the first engineering drawing to be exhibited at the Royal Academy‘s Summer Exhibition.

But the Victorian engineering boom was powered by a few things, including new materials. Cast iron, steel, plate glass and more opened up new possibilities. But they also came with new challenges. And the manufacturing processes in those days were not as reliable as those we have today. So in 1858, Napier set Kirkaldy off on materials testing of wrought iron and steel. Kirkaldy found this work fulfilling and important, enough to make it his life’s work, so when his materials testing duties at Napier were discontinued, he left to strike out on his own.

Kirkaldy’s Testing Works Comes Into Being

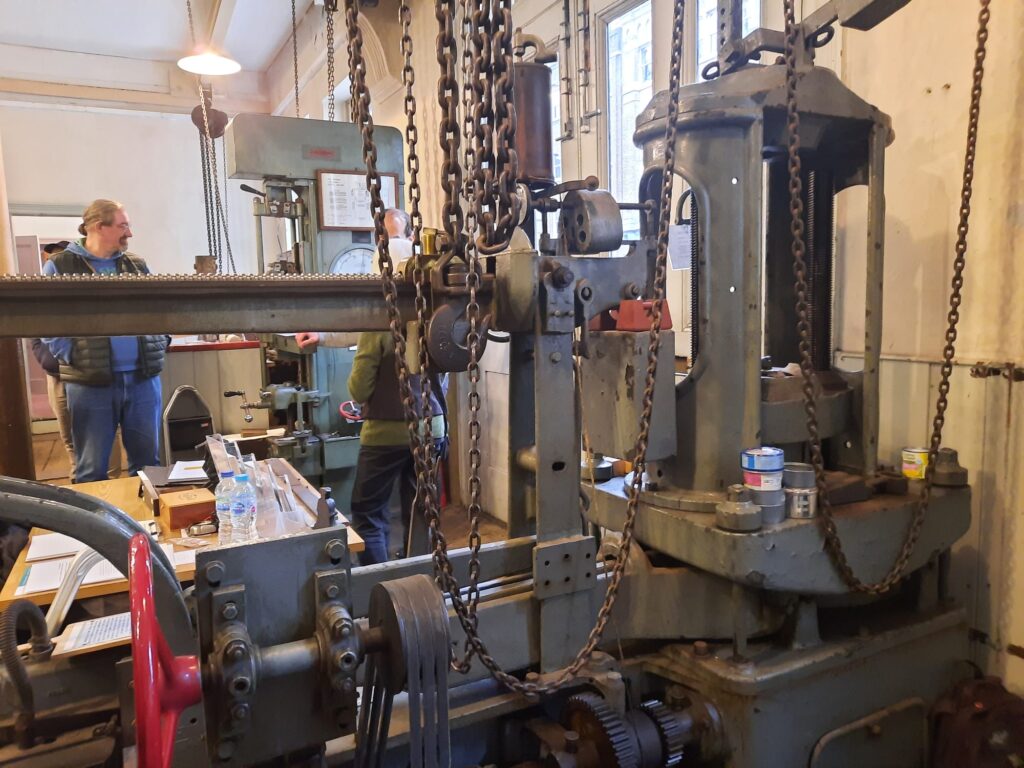

In 1862, Kirkaldy published ‘Results of an Experimental Inquiry into the Comparative Tensile Strength and Other Properties of Various Kinds of Wrought-Iron and Steel’. A riveting read, I’m sure (no pun intended). He then spent some time designing a universal testing machine.* It’s not clear from the historical record how he supported his family during this time, or funded the machine’s manufacturing. But he did, somehow. The Universal Testing Machine he designed was 47 feet and 7 inches long. He commissioned a Leeds firm, Greenwood and Batley, to make it. But they took too long and he got frustrated, so in the end he had it shipped, unfinished, down to London.

Kirkaldy’s first Testing Works was also in Southwark, but not in the spot we’re visiting today. As well as being an industrial area, the reason Kirkaldy wanted to be in Southwark was that it is close to Parliament and so good for integrating a bit of political lobbying into one’s working day. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Kirkaldy set up his testing works, and started testing. This was, at the time, the only independent testing works anywhere in the world. And it was a much needed service: big Victorian building projects, and new inventions, required certainty that the materials they were using were safe. And with inconsistencies in manufacturing processes, the iron columns you bought today might fail where the last batch were fine.

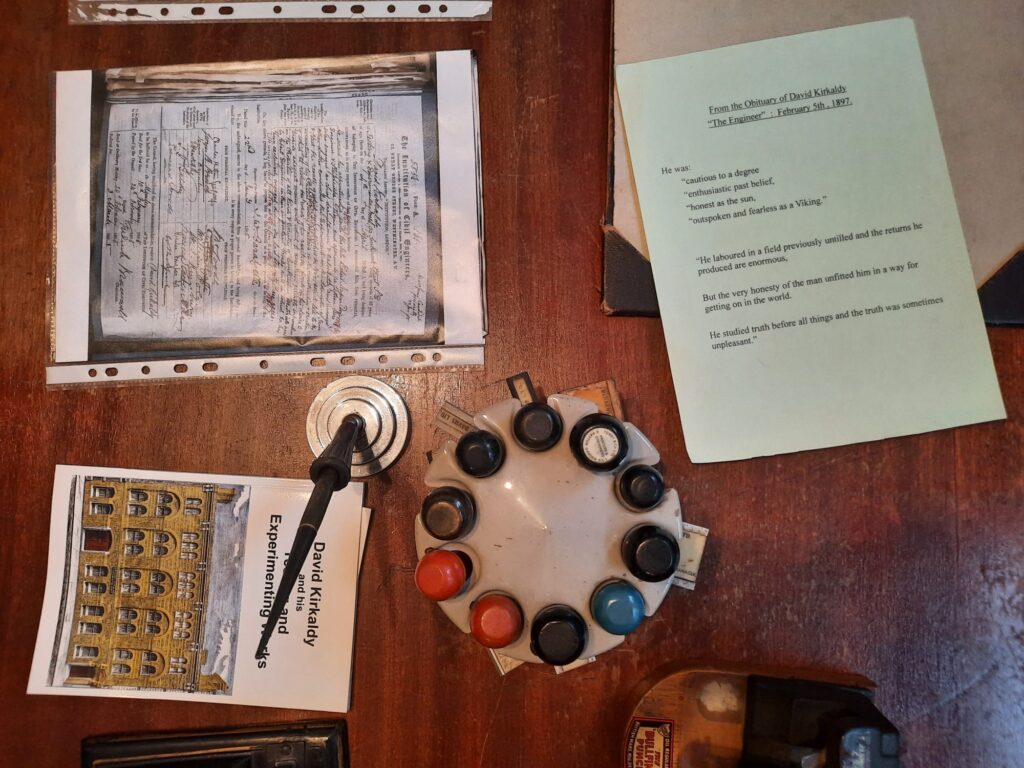

Kirkaldy steadily built a customer base through his thoroughness and uncompromising adherence to the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. The company’s motto was ‘Facts, Not Opinions’. It didn’t always make him popular, but it made him trustworthy. It wasn’t long, therefore, before he needed new premises. He moved into a purpose-built facility at 99 Southwark Street, the same address we’re visiting today.

*’Universal’ as in the same machine could be used to test anything.**

**Anything, as in any building material. The machine essentially applies force – if you put the thing you’re testing in front of the force, it compresses it. If you put it behind the force, it stretches it. Or you can test torsion. So one machine, many materials, all the different tests you need = universal machine.

A Family Firm for Three Generations

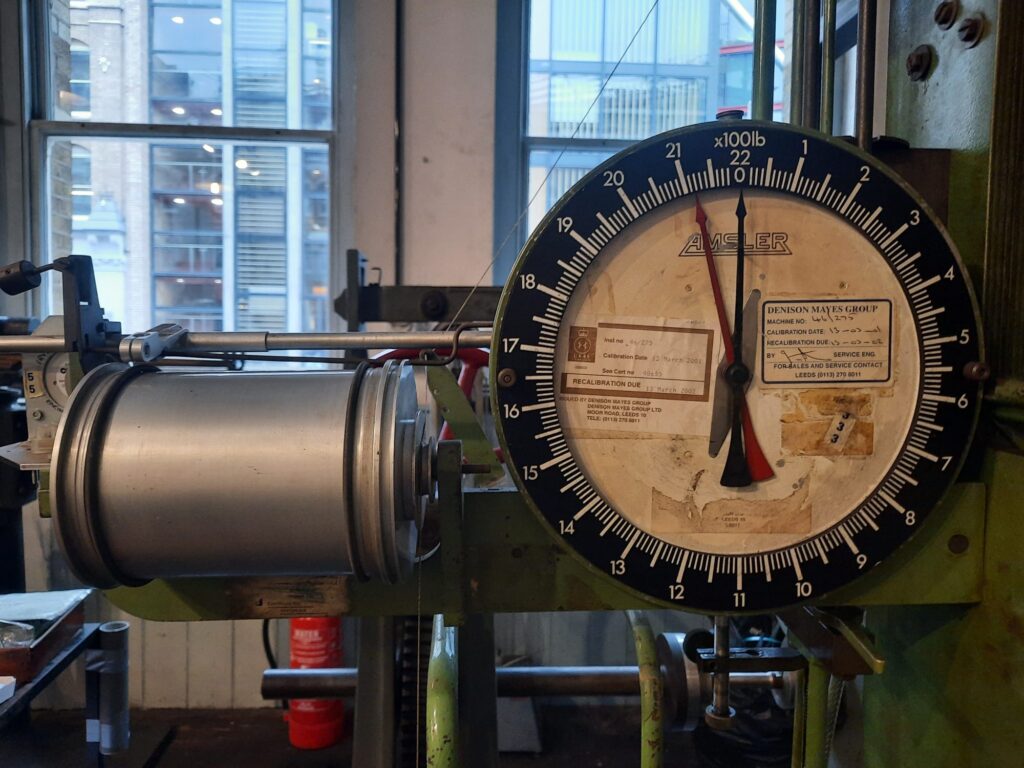

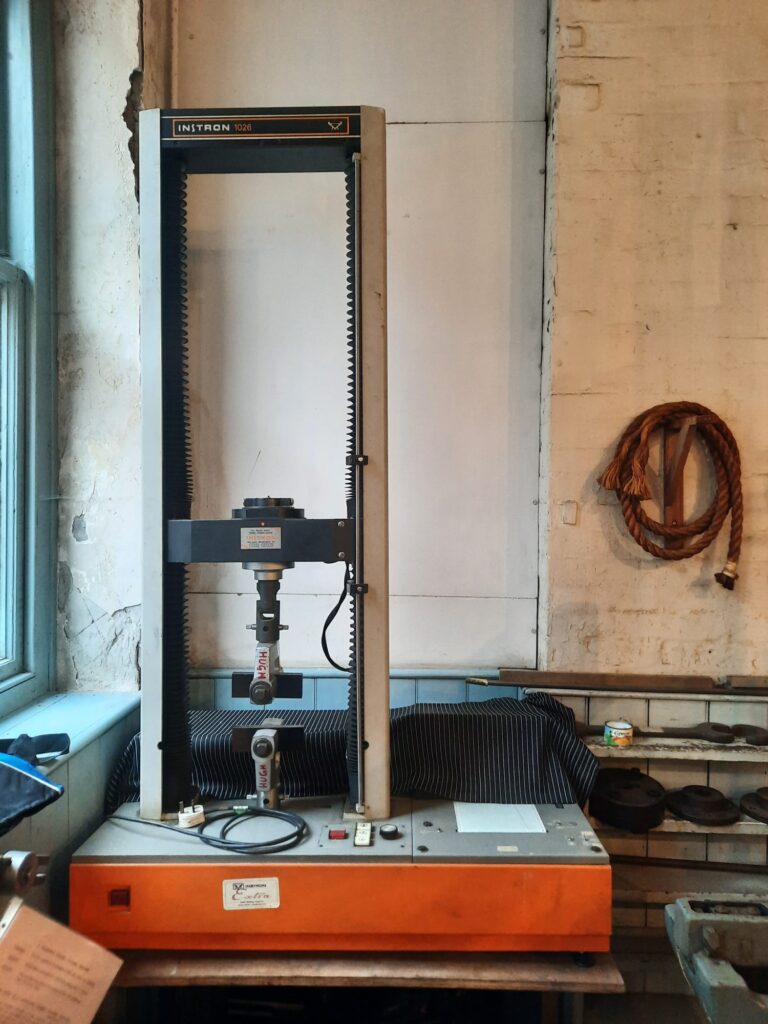

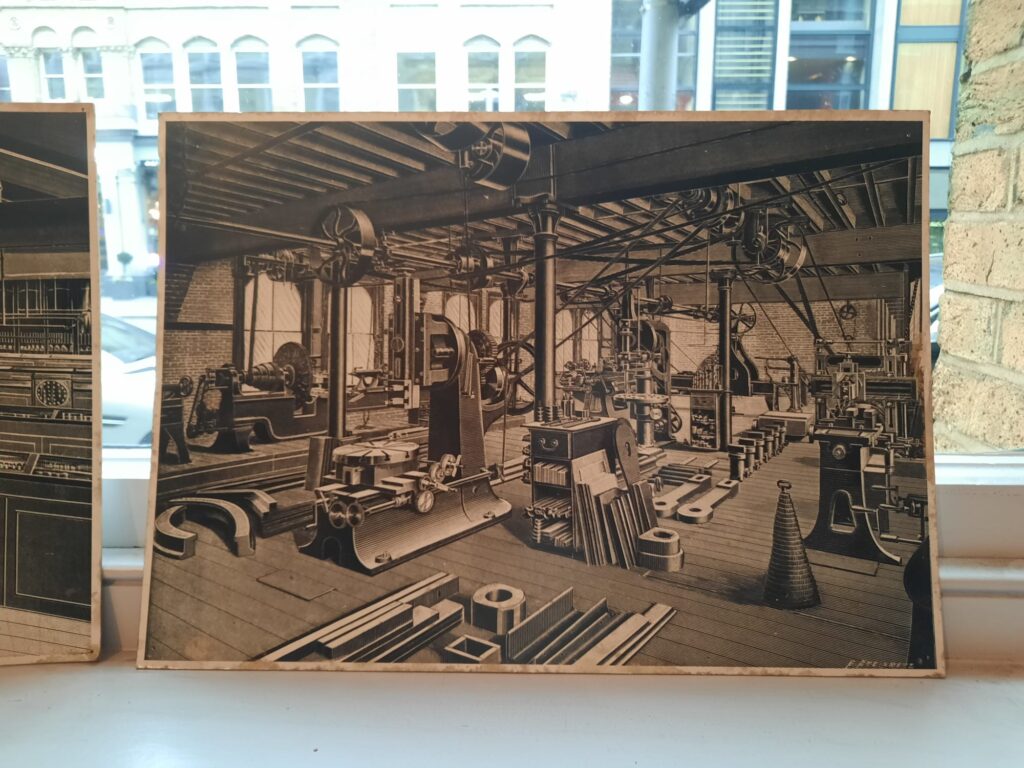

David Kirkaldy continued to run his business successfully for many years. As well as testing materials for commercial purposes, he also tested materials that had failed. Notably, he submitted evidence to an inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster in 1879 (but was furious that the inquiry did not accept all of his results). The bigger premises at Southwark Street meant the firm had space for specialised testing equipment as well as the Universal Testing Machine. Kirkaldy was a pioneer in materials testing, but other companies began to produce machines to test particular materials (like rubber or ships’ chains) or particular qualities (such as hardness). He kept samples from tests in a ‘museum of fractures’ above the workshop.

David’s son William George Kirkaldy (born in 1862) became a civil engineer like his father. He entered the family business as a partner, taking over following his father’s death in 1897. He ensured the firm continued to be well-regarded through participating in publications, competitions and committees. When he died in 1914, his son David William Henry Kirkaldy was only four years old. So William’s widow Annie ran the business with manager Gilbert Gulliver until her son was ready to take over. That was in 1934, after the younger David Kirkaldy had studied at Cambridge and got some real world experience. Under David Jr.’s tenure, the Kirkaldy Testing Works carried out such high profile testing as Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, the Festival of Britain’s Skylon in 1951, and the De Havilland Comet crash in 1954.

David Jr. didn’t marry or have children, and didn’t work until his death like his father and grandfather. When he retired in 1965, he sold the firm to Treharne & Davies. They continued the business for almost a decade before closing it in 1974.

Kirkaldy’s Testing Works Becomes a Museum

In the 1970s Southwark was not then as desirable a location as it is now, so the ground floor with all the machines sat empty for a while. The upper floors became office space. It did get a Grade II heritage listing in 1971, though. Interestingly that was initially on the basis of the building’s exterior only, as in its Italian Romanesque architecture. But subsequent updates to the listing have included the interior and important industrial heritage. With everything taken into account, the building has had a Grade II* listing since 2014.

Ten years after its closure, in 1984, the building reopened as a museum. This was in large part thanks to the interest of Dr Denis Smith, then chairman of Greater London Archaeological Society. The museum, initially Kirkaldy Testing Museum but now back to Kirkaldy’s Testing Works, is volunteer-run. It attracts a lot of retired (and working) engineers and scientists, which is fortunate as it operates on the principle of keeping the machines in working order rather than preserving them as physical artefacts. They open regularly for pre-booked tours, which range from school groups studying STEM and STEAM subjects to quick tasters to ‘machine run’ experiences. In the latter, the volunteers get the Universal Testing Machine fired up and show you what it’s still capable of after more than 150 years!

This is no small undertaking. The Universal Testing Machine runs on a water-hydraulic cylinder. Back in the 19th century (and actually until 1977), this was easier to manage than it is today, by virtue of the London Hydraulic Power Company. This company powered workshop machinery, theatre lifting mechanisms and safety curtains, and more. Without it, Kirkaldy’s Testing Works use a small electric pump. The volunteers must also ensure that elements such as leather seals (original materials but replacement parts) are safe and working as expected.

Visiting Kirkaldy’s Testing Works

On my recent visit, the Urban Geographer and I opted for the full experience. Unless you are visiting London and can only fit in a taster, I don’t know why you would come and not want to see the main event. And the main event, which takes two to three hours and costs upwards of £25, is popular. They sell out in advance, in fact, so make sure you plan ahead.

Kirkaldy’s Testing Works doesn’t keep opening hours outside of tours, so we arrived shortly ahead of time and waited for our group to gather. There were just over 20 of us, so some activities we did together, while for others we split into smaller groups. We started with an overview, before heading downstairs to watch a video. This was quite useful for setting the scene and finding out about the Kirkaldy family. A volunteer then showed us a machine to test the tensile strength of a wire coathanger, which is a neat way to demonstrate at a small scale the forces we would later see at a larger scale in the Universal Testing Machine.

We then split into groups and saw some of the smaller machines. The main challenge here is that, when you’re an engineer who wants to share what they know, an hour or more flies by. We could definitely have spent longer seeing even more machines, but what we did see was already very interesting. We saw the difference between ordinary and tempered steel, and how to test steel for hardness using a Brinell test. There was also a very impressive test of the tensile strength of packing tape. The volunteers explained to us how the marine chain testing machine works, and how concrete is tested. On a couple of occasions they mentioned how various museums would love to acquire one or another of their machines, which are instead kept here in the collection and in working order.

The Universal Testing Machine in Action

All of this is a lot of fun, and would make for a great museum experience on its own. I learned about things that had never even crossed my mind, which I always find an enjoyable experience. There are also a few occasions where a volunteer gets to try a machine out for themselves.

But it’s the Universal Testing Machine which is the main event. It’s a presence right from the start of the tour. It’s the first thing you see when you walk through the door. You can’t hide it, after all, it’s 47 foot long. And there’s various bits of activity and hammering going on as the volunteers get ready. Then, once the other machine demonstrations are finished, everyone gathers around. In David Kirkaldy’s day, I think I heard it only took three people to run the machine. Today, in its old age, it needs a bit more supervision. During our machine run, there were a couple watching the water pressure, and a couple watching the steel sample and ensuring it was secure. One person must also keep a counterweight balanced, which is the method of measuring the material’s performance.

Watching such a clever and historic invention in action is a great museum experience. And I can see how much school groups must get out of it. It brings all the science we had learned up to that point to life. There’s a great excitement around the moment the steel gives way. It’s actually a very multi-sensory experience: the workshop smell, the sights and sounds, and then feeling the heat of the metal. No tasting though, please!

Whether you come from an engineering or science background, are interested in the history, or just want to experience a London curiosity, I recommend Kirkaldy’s Testing Works. And it’s definitely worth booking in for the full experience including machine run. That the museum is entirely volunteer-run makes it all the more impressive: I hope they’re able to continue David Kirkaldy’s legacy for years to come!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.