Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350 – National Gallery, London

The National Gallery uses its art world influence to bring together an astonishing array of works in Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350.

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350

Phew, I’ve finally managed to stop rushing around exhibitions that are closing, and get to a few that you might still have a chance of seeing, too. And one benefit to the mid-exhibition visit is that it’s sometimes a bit quieter. Just as I normally complain that Tate Britain exhibitions are too big (most recently here), I normally complain that National Gallery exhibitions are too busy (most recently here). And I’m not saying that Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350 wasn’t busy. We’re talking about a major London institution, after all. But it was a normal kind of busy, not packed. Maybe it’s just that this exhibition is less of a blockbuster than some others. I hope it may also be that I’ve finally cracked it, and the mid-run visit is the key!

So why do I say that this is less of a blockbuster? Well, the lack of star artists, for one. The last busy exhibition I was complaining out featured paintings by Vincent Van Gogh. But the Lorenzetti brothers are hardly household names. That’s the point here, I think. The National Gallery quite unashamedly mix crowd-pleasing and academic exhibitions on their calendar, and this one tends towards the latter. It’s certainly an important moment in art history that’s under discussion.

If we think of one Italian city-state associated with the Renaissance, it’s… not Siena. It’s Florence. But the fact is, the conditions that fostered this explosion in artistic expression and technique existed, in some combination, elsewhere in what we now call Italy. Siena, in the 14th century, was wealthy. It had a stable government. There were plenty of patrons around, both religious and secular. And as a centre for trade and pilgrimage, artists in Siena were exposed to new ideas and styles. Perfect, really, for a few talented artists to come along and make their mark.

Why 1300-1350?

The exhibition makes the case for the first half of the 14th century being a critical moment in Siena’s – and art – history. I’ve mentioned some of the factors that contributed to this, but let’s look at them again in a little more detail.

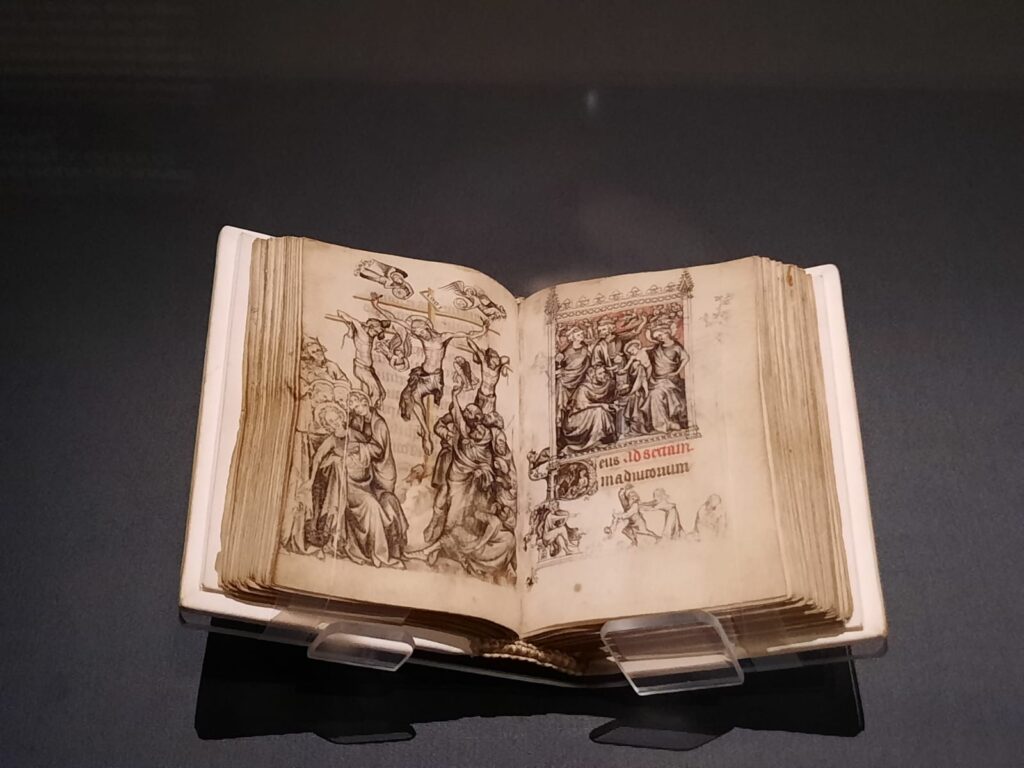

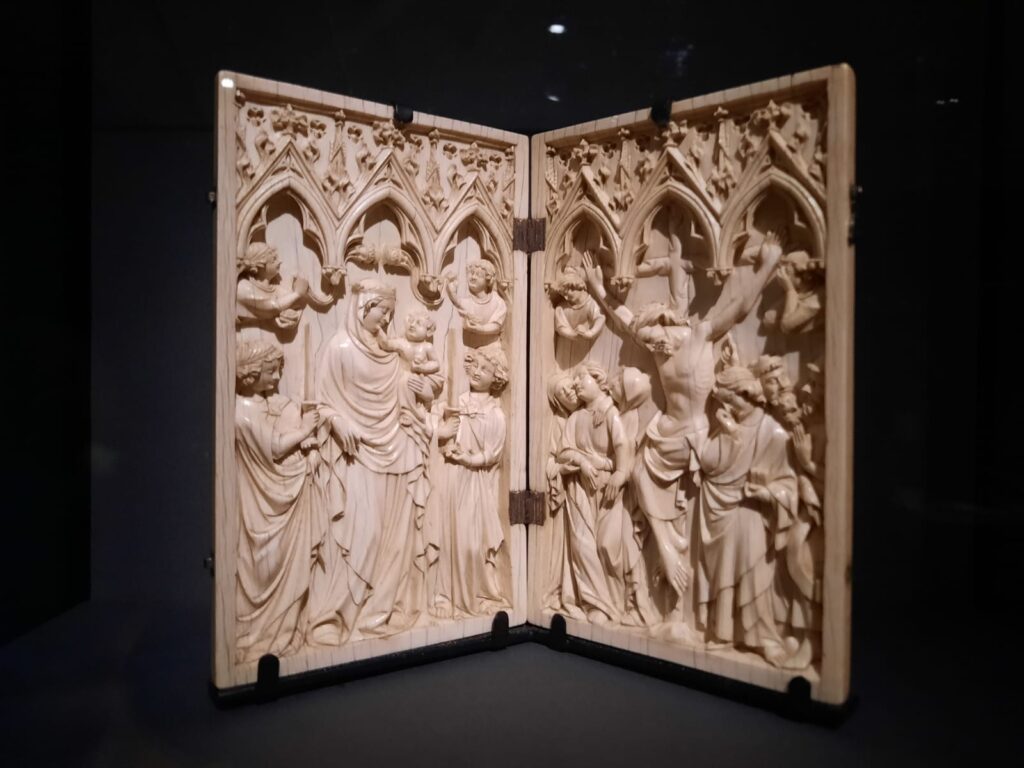

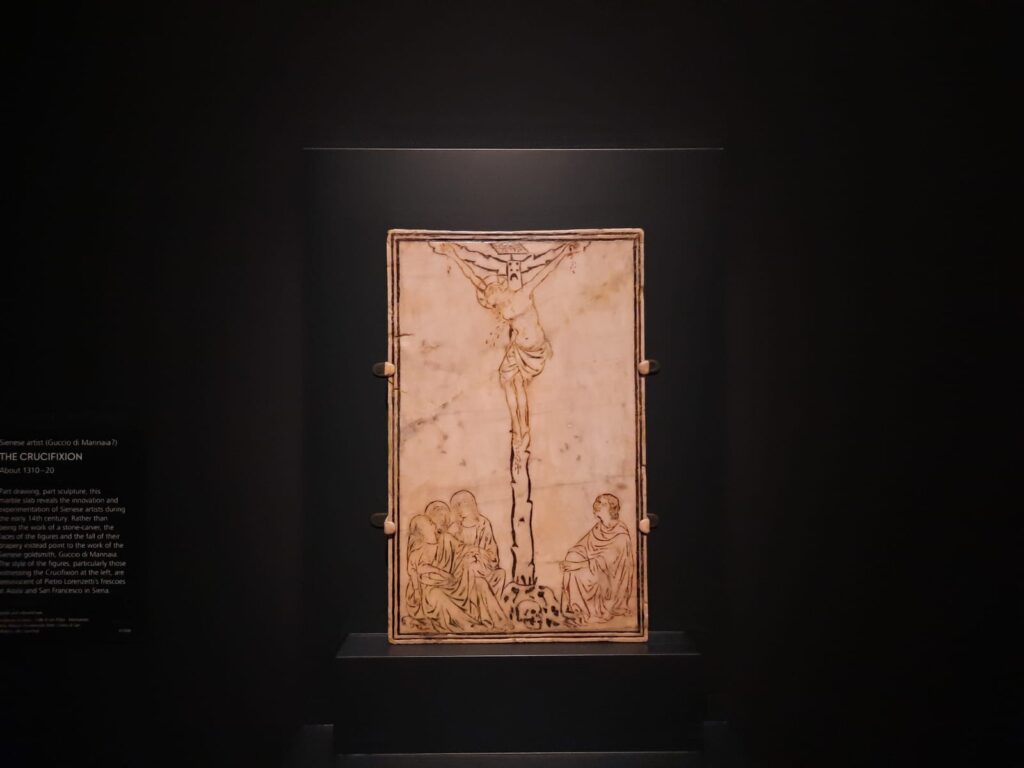

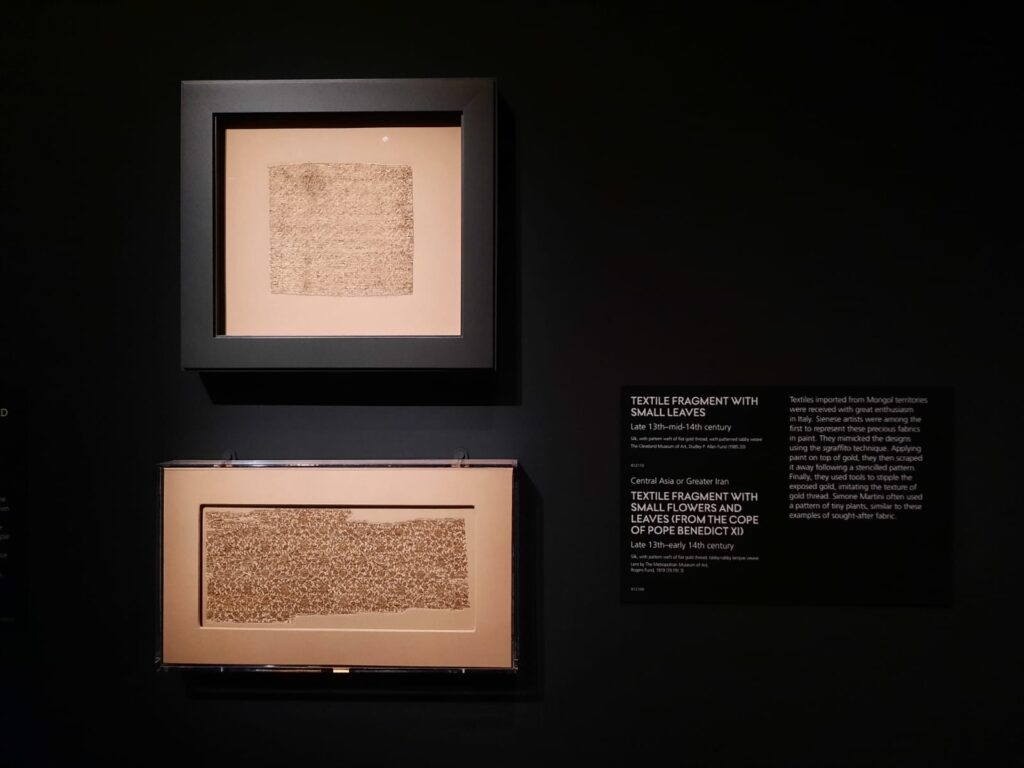

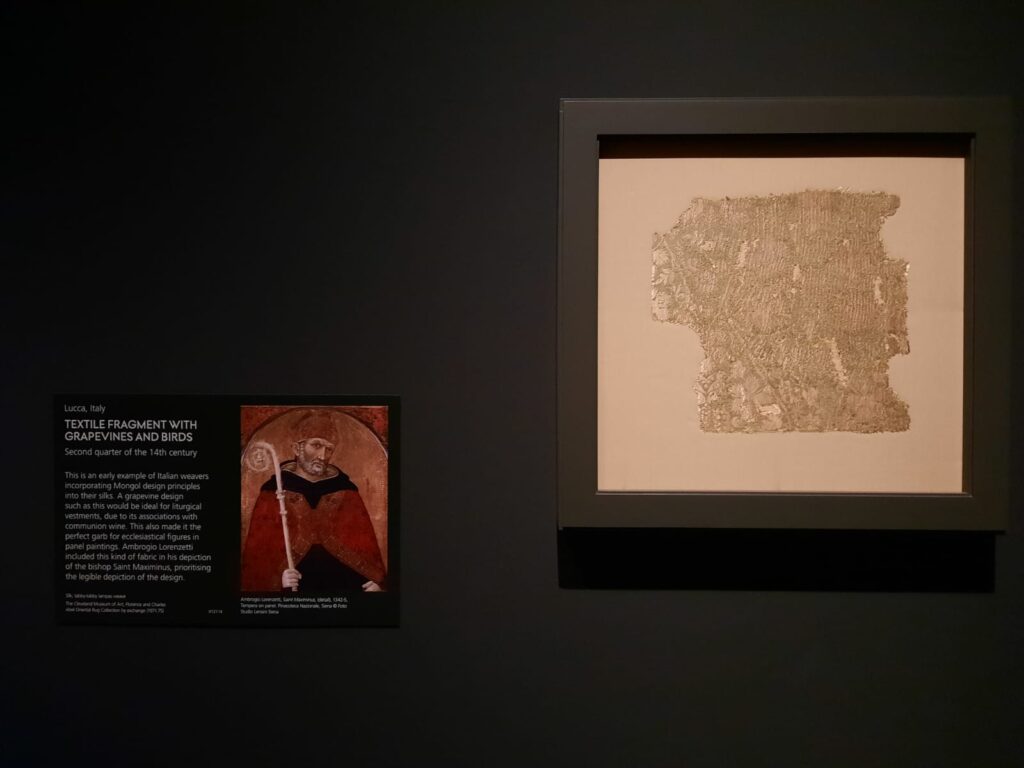

Firstly, Siena was one of the first banking centres in Western Europe. This meant prosperity, which means art patrons – whether for private devotional objects or more public displays of faith (and wealth). Siena was also a cosmopolitan place where you could encounter new types of objects, or ideas. Several times throughout the exhibition we see examples of how Sienese artists encountered Gothic works from France and adapted them into their own context. There’s also a whole section on textiles which came from the east, were worn or recreated locally, and found their way into paintings. Siena’s status as a trade centre and a stop on the via Francigena pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome enabled this cultural exchange.

And lastly there’s Siena’s government. It was an unusual model: Siena was ruled by ‘the Nine’: a council of men elected every two months. But importantly, it was stable. As we see from the current volatility of the art market faced with economic uncertainty, it’s easier for artists to win and work on commissions in times of peace and stability.

Why does it end in 1350, then? Well, any guesses as to what else was going on around this time? Full marks to those who said the Black Death. Bubonic plague absolutely ravaged the population of Europe, Asia and Africa. And being a trade centre and on a pilgrimage route suddenly seems less convenient in this context. Siena suffered as almost all cities and towns did. Some of the artists under discussion likely died. In its aftermath, art was not as high on the agenda. But Siena’s artistic experimentation did have a lasting influence, as the exhibition demonstrates.

Telling the Story of Painting in Siena

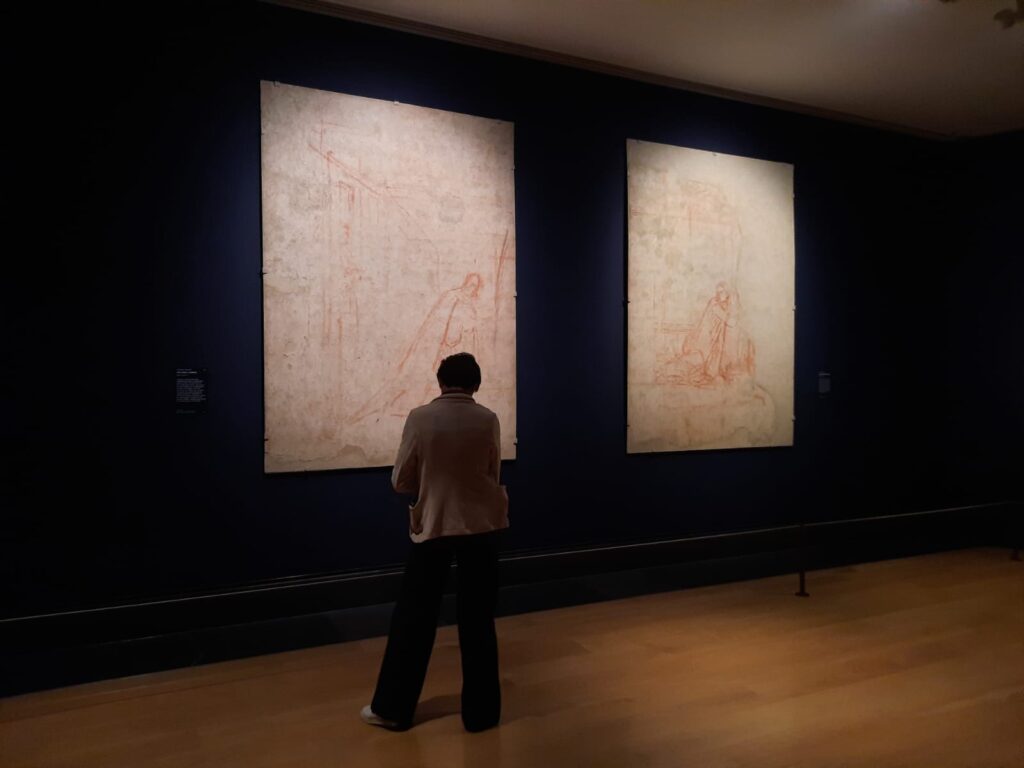

The secondary exhibition space at the National Gallery (the Sainsbury Wing having only just reopened) is a curious one. It’s almost like a hub and spoke layout. You enter, follow the flow for a couple of rooms, pop into some side rooms, follow the flow again to find the exit, where you have to go up and over and through endless rooms of the permanent collection to get back to where you started. It’s a physical space that sometimes helps curators to tell a story, and sometimes is a hindrance.

I made that detour because I’m always interested to see how the curators respond to the space. Bearing in mind that, on this occasion, the exhibition is a collaboration between the National Gallery, and the Met in New York. Anyway, on this occasion, as I mentioned previously, the exhibition focuses on some specific artists. Four of them, in fact: Duccio, Pietro and Ambrogio Lorenzetti, and Simone Martini. The Lorenzettis were brothers (going by archival evidence).

I liked this approach. Firstly, as a reasonably academic exhibition topic, it was nice to focus on different artists in turn. By seeing multiple examples of their work, you can get a bit of a sense of them: their style, compositions, the types of commissions they received (or at least those that have survived). Focusing on individuals who must have known each other personally and professionally also gives a nice sense of an artistic community in Siena. Additionally, by foregrounding individual biographies, the exhibition allows viewers to consider how each artist’s career intersected with the civic, religious, and political institutions of Siena. All those depictions of the Virgin Mary, for instance, weren’t just a preference of the artists: she was (is, I guess?) the patron saint of Siena, and as such it behooved them to continue to draw inspiration from her story.

Themes Emerge Beyond Merely Painting

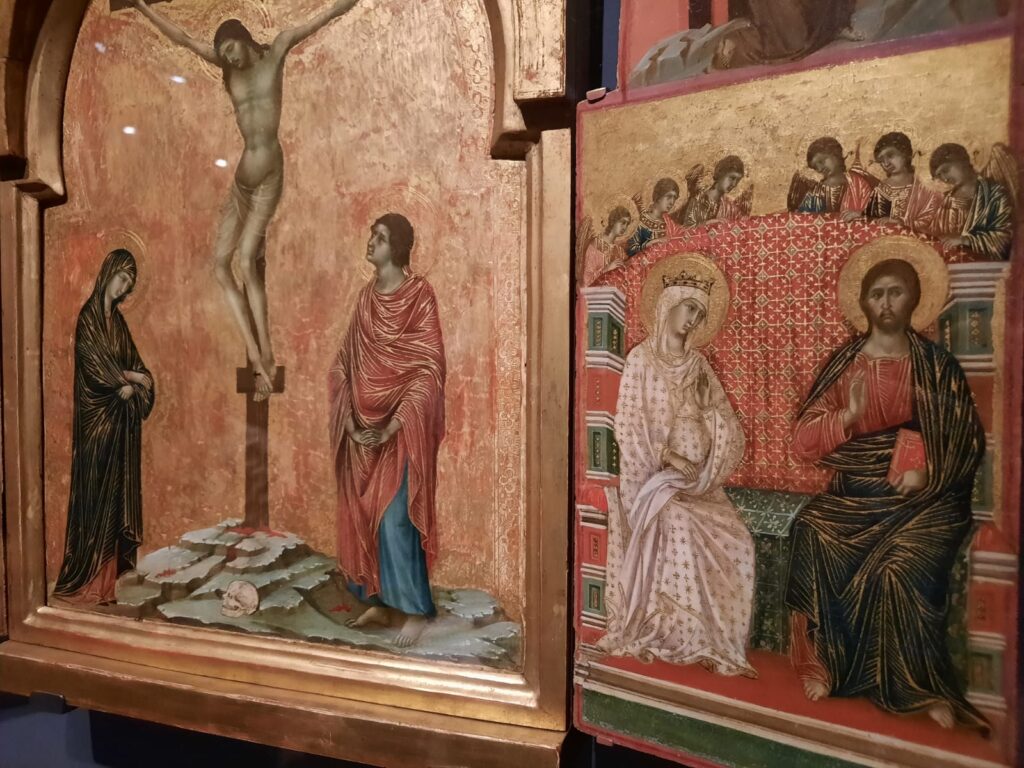

Coming back to the hub and spoke layout of this exhibition space, it would lend itself very well to this biographical approach, in theory. Start, as the curators do, by setting the scene with a few Byzantine-style icons. Remind everyone why these Sienese paintings are so innovative. Then Duccio was the earlier of the artists, so start with him. By the time you get to the central space with side rooms, you can cover the other artists. Then there’s room to show their legacy before the exhibition ends.

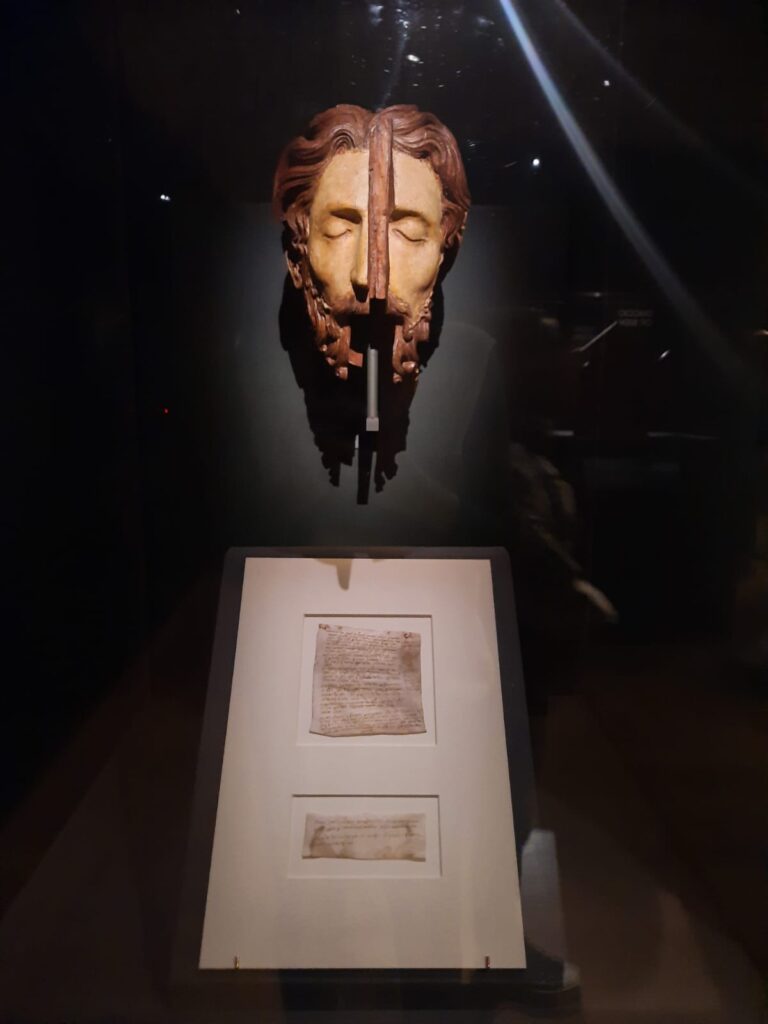

This isn’t so far removed from the flow of the exhibition. But what kept confusing me a little was the alternation of individual artists and broader themes. We do have the artistic and historic background first, followed by Duccio. His masterpiece, the Maestà altarpiece for Siena Cathedral, occupies the hub of the hub and spokes. Two of the spokes focus primarily on major works by Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti. But suddenly we’re actually looking at connections between this Lorenzetti and Tino di Camaino, not even a painter but a sculptor. Then it’s religious devotional objects and the depiction of textiles, before we see more work by the Lorenzettis. The exhibition finishes with the legacy of this fruitful period in Siena, particularly at the papal court in Avignon.

It’s not that these additional themes weren’t interesting. It’s just that I thought I was seeing an exhibition about four artists, so was surprised when we kept switching to broader themes before we’d finished with the biographical approach. Maybe the exhibition layout is actually chronological, first and foremost? That would explain why we meet the artists in order, with contemporary trends inserting themselves in between.

The Legacy of Siena

One of the interesting legacies of this generation of Sienese painters – Duccio, Simone Martini, and the Lorenzetti brothers – is how their influence extended well beyond Siena, particularly to the papal court in Avignon. Simone Martini, in particular, plays a pivotal role here. He actually literally took Sienese painting to the papal court, moving there in the 1330s and dying in Avignon in 1344. The works he produced there, helped to transmit the elegance, linear refinement, and emotional nuance of Sienese painting into a broader international context.

This isn’t just a matter of stylistic export, but of sensibility. The emphasis on grace, storytelling, and beautifully controlled surfaces became a hallmark of what we now call the International Gothic style. While the rest of the exhibition shows artists in Siena incorporating different styles (French Gothic, Northern European) into their art, we have to take the curators’ word for the influence they had in the other direction, on painters in France, Bohemia, and even later in early Netherlandish painting.

More broadly, the Sienese commitment to clarity of narrative and decorative richness left a distinct mark. It’s a separate tradition to the Florentine emphasis on volume, anatomy and emotion (think Giotto), but also important to art history. So, while Siena’s ‘golden age’ was relatively short, its visual language had an unexpectedly long afterlife, particularly in courts and ecclesiastical settings where refinement and visual rhetoric still counted for more than naturalism.

A Coming Together of Siena’s Masterpieces in London

Finally, I want to share another aspect of this exhibition which I really enjoyed. And again this is a point I’ve made before, which bears repeating here. One of the great things about seeing exhibitions at major institutions is their sway. Their star power. When used to bring together the best of the best, I love it. And here we have not just the National Gallery’s pull, but the Met’s, too.

You can get a sense of how this manifests by reading the labels carefully. The panels from Duccio’s Maestà, for instance, are dispersed to many different locations. They haven’t been together like this probably since they were sold off. Likewise pendants that are back together for the first time in decades (or longer). And there’s a very special example to finish with. Simone Martini’s Orsini Polyptych. If you know the words diptych and triptych, you’ll realise a polyptych is made of many separate elements joined together. It’s a private devotional work, which Martini painted for Cardinal Napoleone Orsini. You could close it up like a book, open it to an Annunciation scene, or unfold the whole thing to reveal Christ’s death and torture. However, over the centuries it has not remained intact. This exhibition reunites them after an interval of centuries, from the Louvre, Belgium, and Berlin.

And so, even if your current interest in (or knowledge of) the art of Siena is limited, in my opinion this is an exhibition worth visiting. It brings so many wonderful things together that if you can’t make it to Siena, this is a good substitute. And all of those painstakingly reunited works will go back to their home institutions once they’re done in London. Do take the time to see them while they’re here!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300-1350 on until 22 June 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.