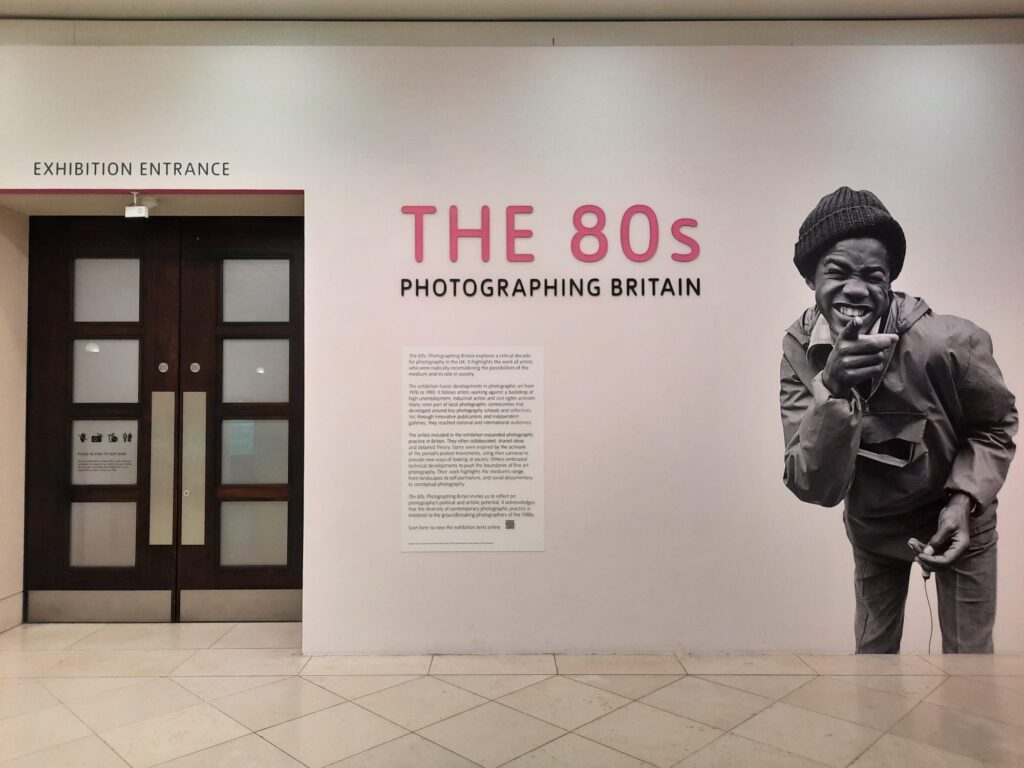

The 80s: Photographing Britain – Tate Britain, London (LAST CHANCE TO SEE)

Another expansive Tate Britain exhibition, The 80s: Photographing Britain focuses a political lens on this crucial decade in modern British history.

The Eternal Torture of Exhibition Schedules

That’s a dramatic title now, isn’t it? Good to write something attention-grabbing every now and then. And frankly my list of exhibitions, many of which are in the process of closing, has me feeling a little dramatic. I always have good intentions, but I also always end up chasing the ones that are closing rather than seeing the ones that are opening. Much easier with theatre where I have plenty of press nights to keep me busy and seeing things at the start of a run.

All of this is a long-winded way of apologising to you, dear readers, for another review where you’ll have to be quick if you want to see the exhibition for yourself. You’ve only got a couple of days, in fact. But if you are not inclined to rush around seeing exhibitions before they close like I am, or if you’re not in London, then hopefully this post will give you a feel for it. And I’ll do my best to get to a few new exhibitions for you soon!

But what are we even talking about? The exhibition under discussion today is The 80s: Photographing Britain. It’s in the very large Tate Britain exhibition space where we’ve seen this and this amongst other exhibitions. It probably goes without saying, therefore, that I’m going to complain about sheer size at some stage. But let’s see what else I have to say!

The 80s: Photographing Britain

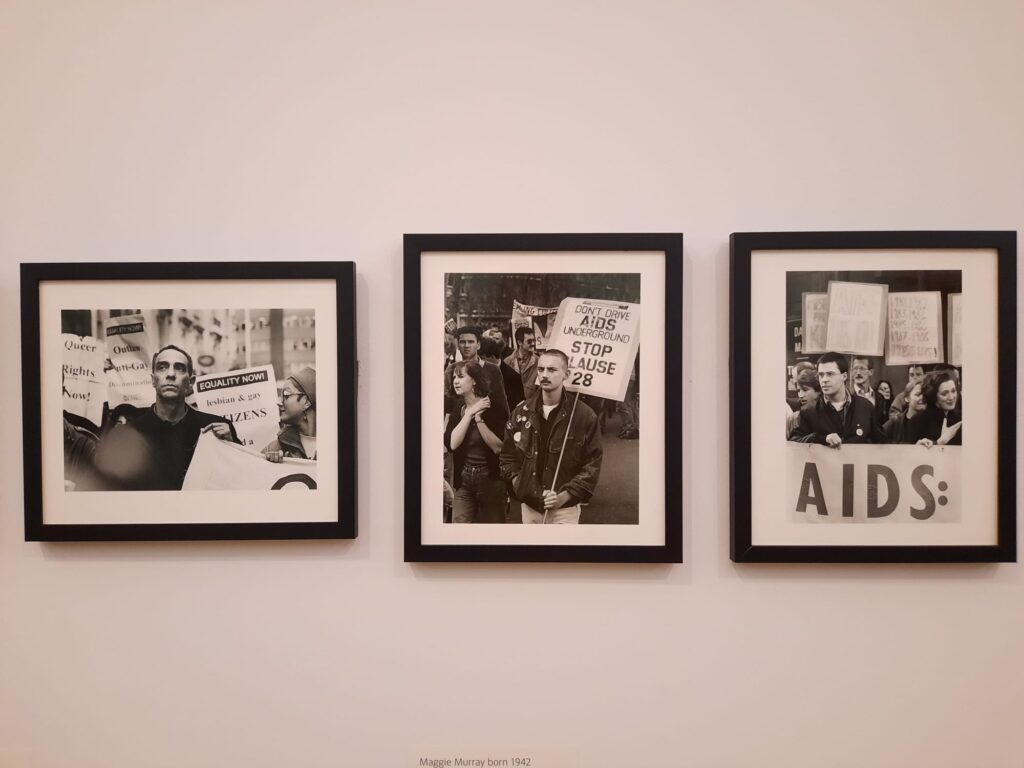

Let’s start with a couple of questions. Why the 80s? And why Britain? And maybe why photography, too? I’m going to start by suggesting some things you might think about on the topic of Britain in the 1980s. How about Margaret Thatcher? Miners’ strikes? Charles and Diana? The Falklands War? There was a lot going on. Not just in the UK: there was Reaganomics, Michael Jackson, the AIDS epidemic… A busy time.

But thinking about Britain today, the 1980s had a sizeable impact on contemporary society. Just look at how many politicians seem to worship Margaret Thatcher, and the style of politics this influences. Breaking the power of unions changed the types of work we do, and how we do it, forever. People fought for rights and against discrimination, moving us forward (even if some of these advances seem increasingly fragile).

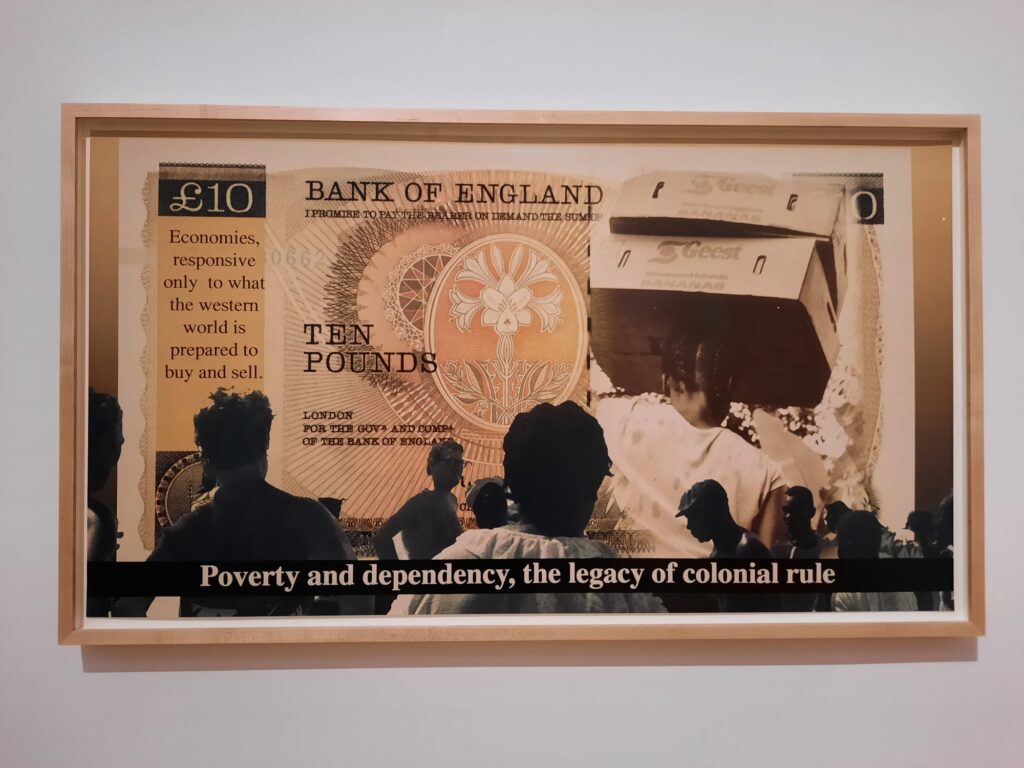

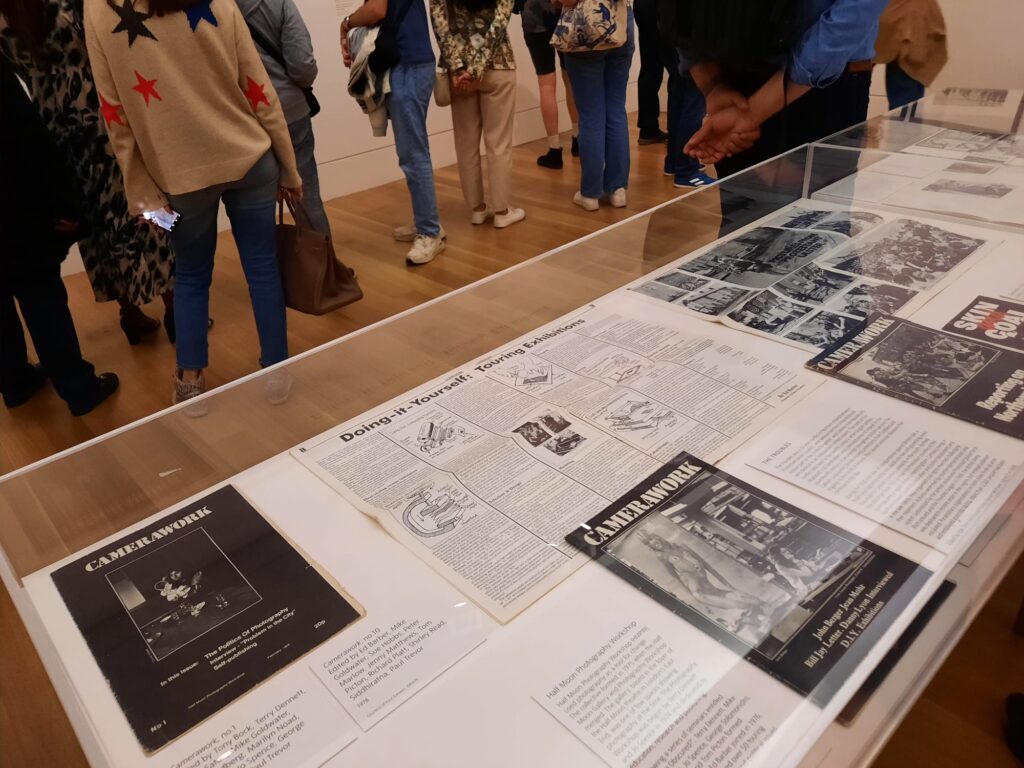

And to come to “why photography?: this exhibition posits photography as something very political. On the surface it seems like a fairly neutral thing: press the shutter and it reflects a little rectangle of reality. But when you press the shutter, how you compose your image, who is photographed and who isn’t: these are all decisions which influence how we understand news stories, big events, new trends, and ultimately the world around us. So yes, The 80s: Photographing Britain, let’s go!

Representing a Decade

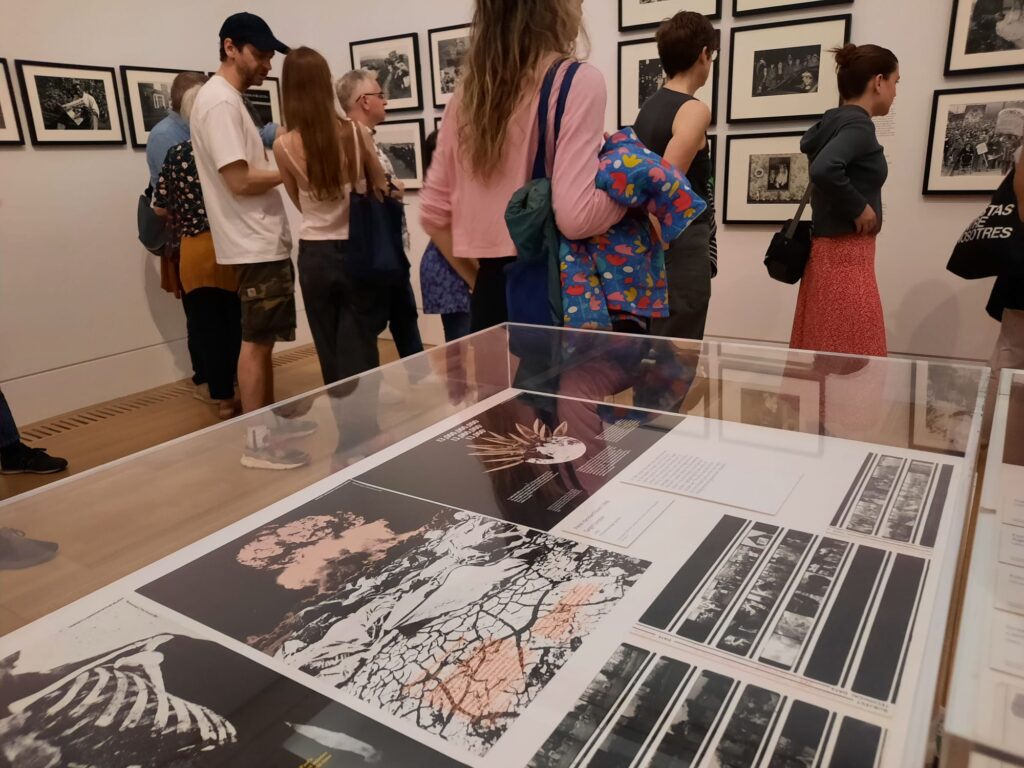

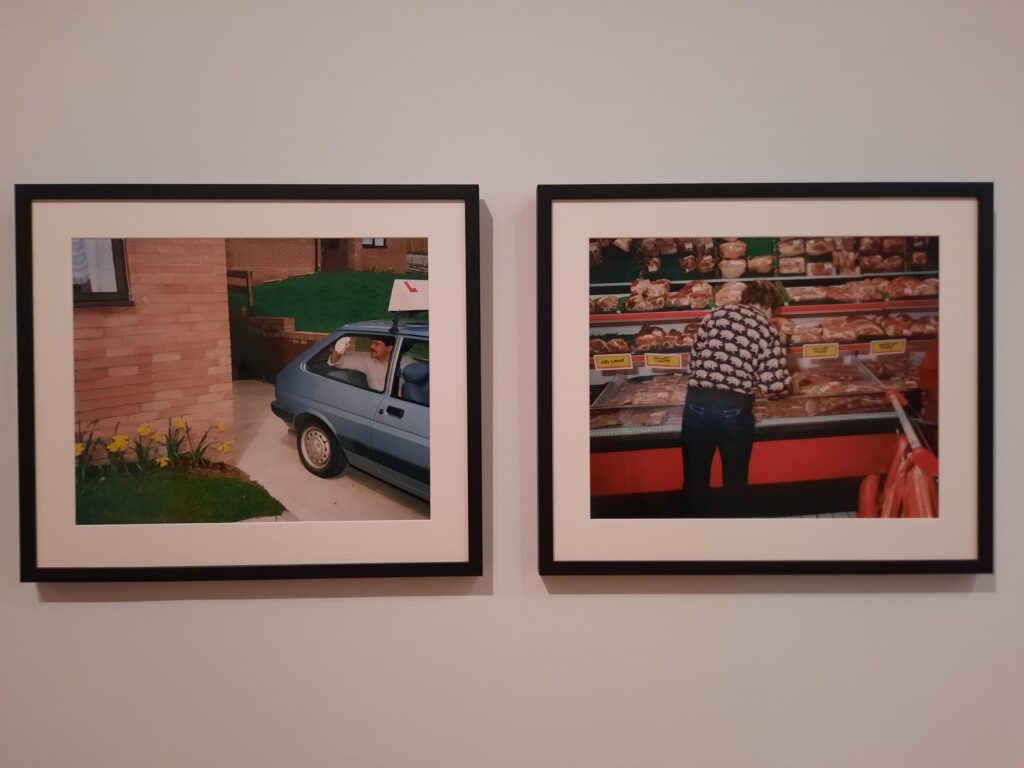

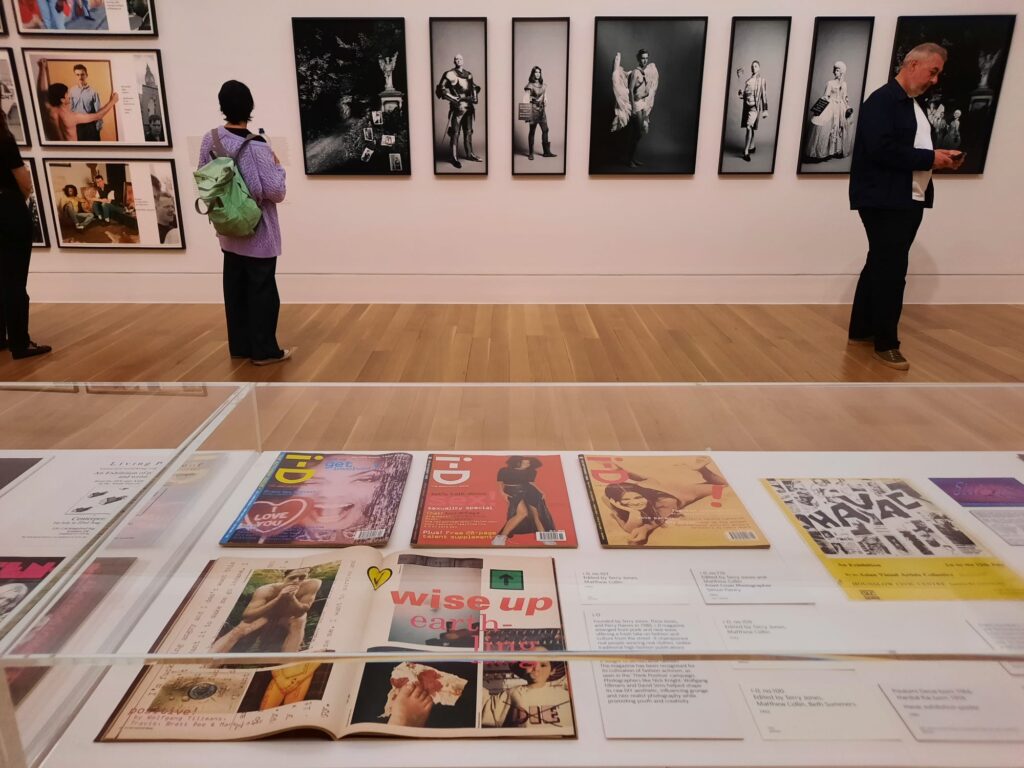

As I mentioned above, the Tate Exhibition space is immense. They’ve got another one upstairs which I feel is slightly more manageable. So the curators had room to play with. They’ve broken the topic down into smaller themes, a mix of subjects and technical developments. Things like landscapes, combining images and text, colour photography, the Black experience, or subcultures.

Let’s get my usual complaint out of the way. It’s so big. There’s so much to take in. It’s a subject I find very interesting, but for each room there’s a new topic to take in in terms of the historic, social and photographic context. Then each image or series of images has a text with specifics about the event or person depicted, sometimes how the photographer set up the shoot, reflections on it, the photographer’s biography, high level technical information etc. There is a wealth of rich detail, which together does give a sense of Britain over a decade (and a slightly long decade: the late 1970s and early 1990s sometimes sneak in). But man it’s a lot to try to get your brain to absorb.

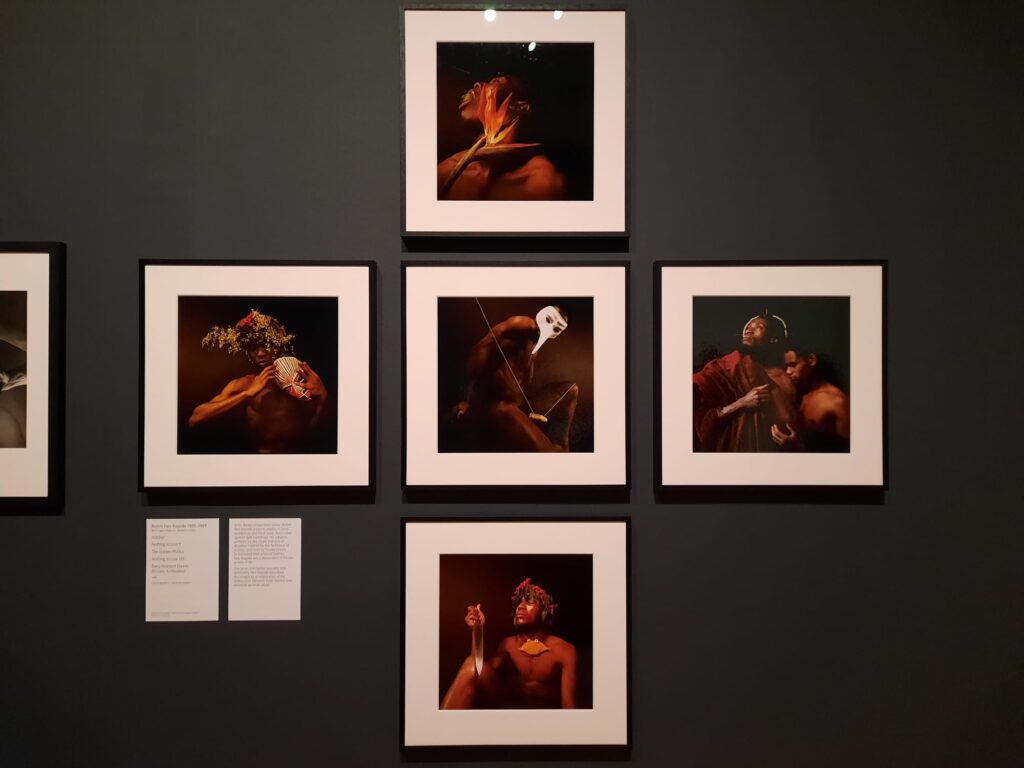

My experience of trying to do this was similar to other exhibitions in this space. I knew what I was getting into, so didn’t try to read everything. But as I went through and my brain filled up, I read less and less. Very little by the end of the exhibition. Which is a shame: Black Bodyscapes and Celebrating Subculture were the last two themes and are ones I’m really interested in. In the former I was pleased to recognise work by Rotimi Fani-Kayode as I’d seen recently at Autograph. But I was ready for a debrief in the cafe. And I don’t think I was alone: the rare seating throughout the exhibition was well-occupied.

On the flip side of this: if I know this about the space, is it not the definition of madness to keep going and expecting not to have the same outcome? That one is on me.

A Few Highlights from The 80s: Photographing Britain

I was quite pleasantly surprised by how few of the photographers I recognised. I love encountering new artists. There were a couple of series beloved of curators: I think I’ve seen Chris Killip‘s Seacoal series, in which he spent time with a community gathering coal from the foreshore, in about two other exhibitions in the last year or so. It’s a great one, so no wonder. I’d also seen work by Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen very recently.

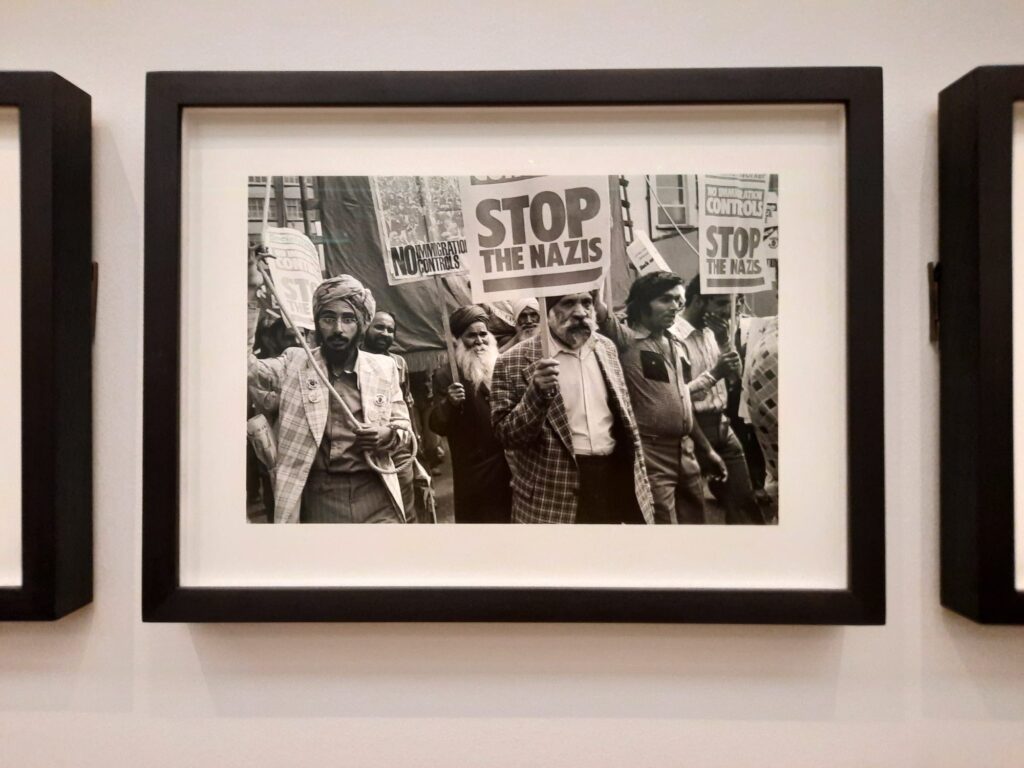

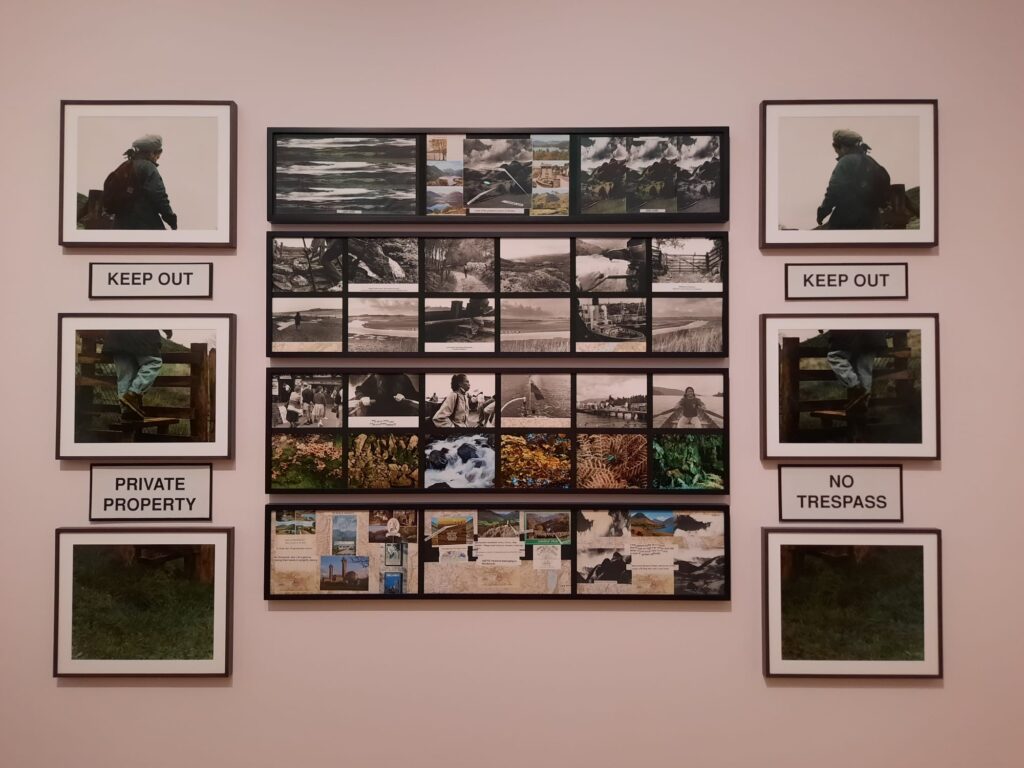

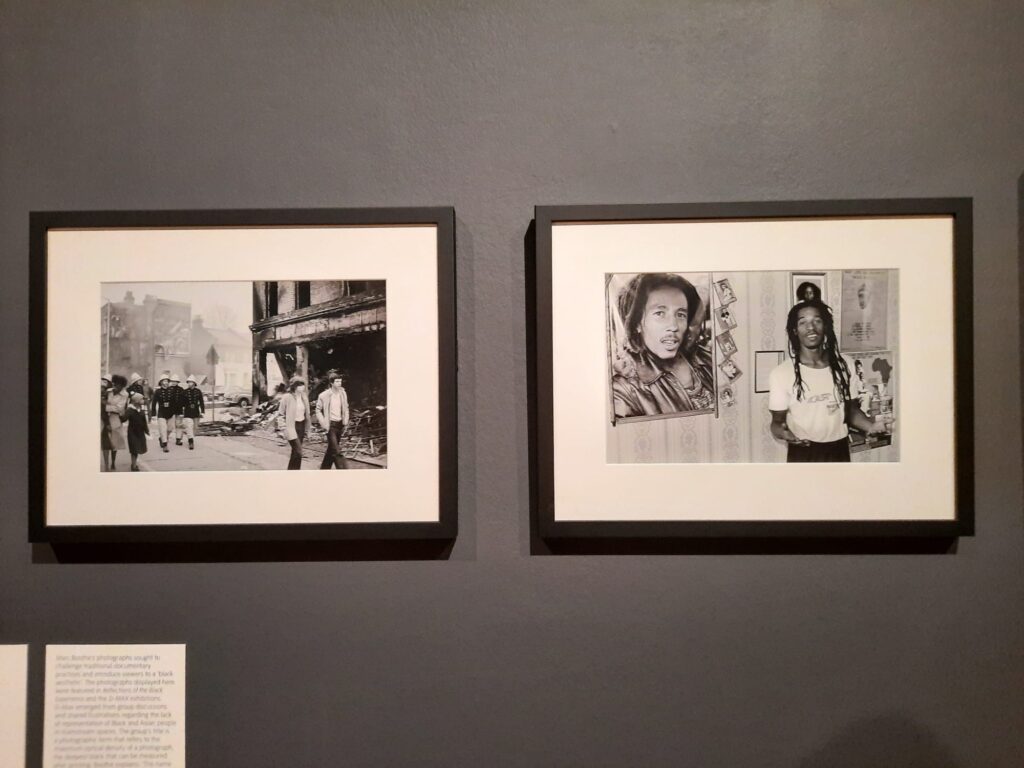

Otherwise I was more likely to know the events but not the photographers. I was fascinated, for instance, by some of the images of protests in New Cross, close to where I live, by Syd Shelton and Armet Francis. This is where the artistic, documentary and storytelling qualities of photography combine. It’s a great insight into history that’s very local to me. Likewise there are images of the Miners’ Strikes and other iconic events: some of the images iconic in themselves and others looking at familiar stories from different angles.

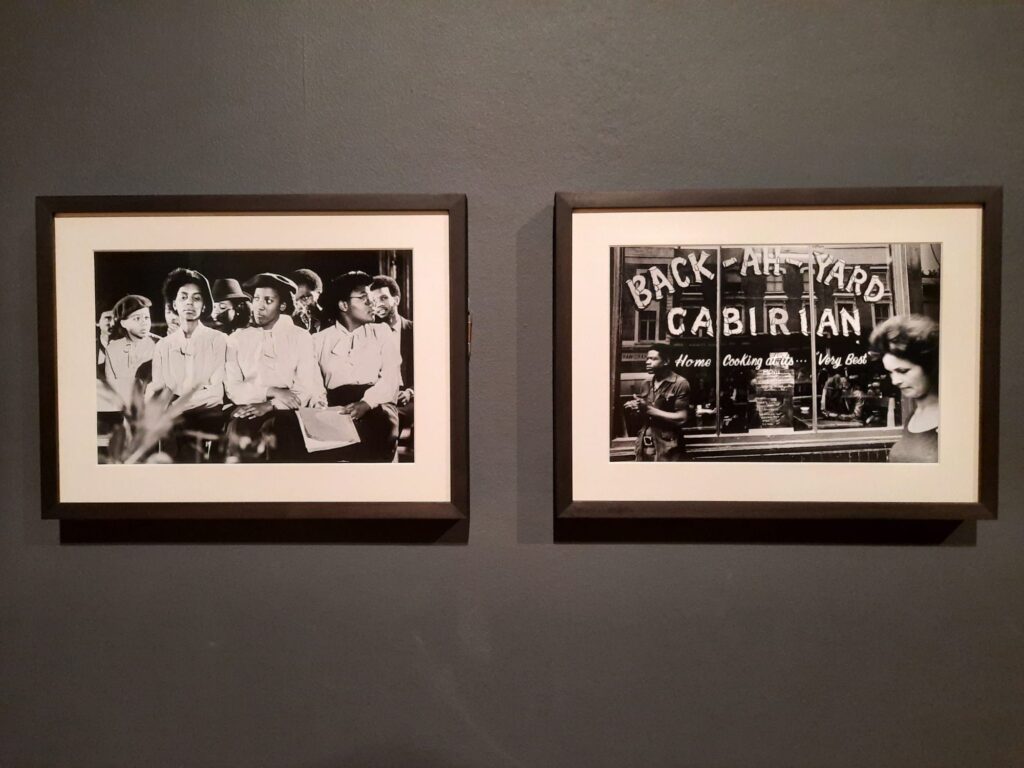

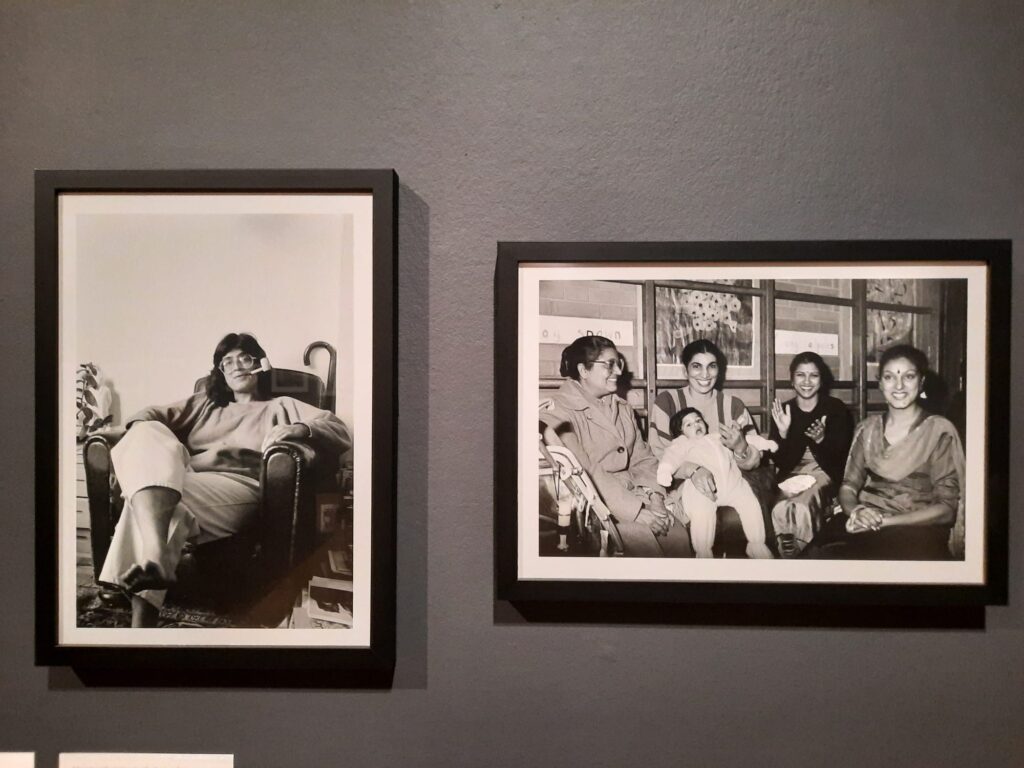

One thematic grouping I would love to see expanded into its own exhibition was Reflections of the Black Experience.* The title comes from a 1986 exhibition at Brixton Art Gallery organised by the Greater London Council’s Racial Equality Unit, but the space also reflects on D-MAX: A Photographic Exhibition mounted in response to the former. There’s a lot to unpack here, the idea of ‘political Blackness‘ as an organising tool, for a start. This helps me to better understand the origins of Autograph as an organisation (originally the Association of Black Photographers). The photographers in this section, including Armet Francis who I mentioned earlier, Marc Boothe, Sunil Gupta (another familiar name) and Mumtaz Karimjee, vary in their subjects and techniques but are united in portraying their subjects free from preconceived expectations.

*Two sections of the exhibition focusing on Black (or politically Black) photographers had black walls. I think I understand the intent but I wasn’t quite sure about it in practice.

A Few Final Thoughts

So what do we make of all this? Like many a Tate exhibition, there’s an awful lot to see here. And to learn. So much, in fact, that it represents the biggest challenge. But it also means that most visitors will probably find something that interests them in what is really a very broad survey with a reasonable depth of detail.

I think what I took from The 80s: Photographing Britain was a feeling of empowerment. There is a barrier to entry for participating in photography (less so today when everyone at least has a phone), but it’s still a fairly accessible medium. A photographer’s ability to tell a story of their choosing relies on a good eye, building relationships, being in the right place at the right time, and knowing their craft. You can photograph yourself, your loved ones, strangers, landscapes, combine words and images, and so much more. And by all of these photographers doing this, we have a partial visual record of a decade that has more life, colour, depth, feeling and truth (whatever that is) to it than most media. It’s a point fulsomely made.

So even if I didn’t fully enjoy the gallery experience, as my head swam with information and I longed for fellow visitors to budge up so I could sit down, I appreciated the intent. For the most part. I don’t know which audience this exhibition works best for, whether photography enthusiasts or amateurs. Those learning about the 80s or those who lived through it. And maybe the need to wade through so much content is partly what makes this a solid exhibition rather than a great one, at least for me.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

The 80s: Photographing Britain on until 5 May 2025 only.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.