Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits – Kenwood House, London

In Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits at Kenwood House, John Singer Sargent’s luminous images of Gilded Age heiresses reveal women wielding beauty, money, and portraiture to cross oceans, claim titles, and shape their own mythologies.

Heiress at Kenwood House: A Fitting Setting for Transatlantic Dreams

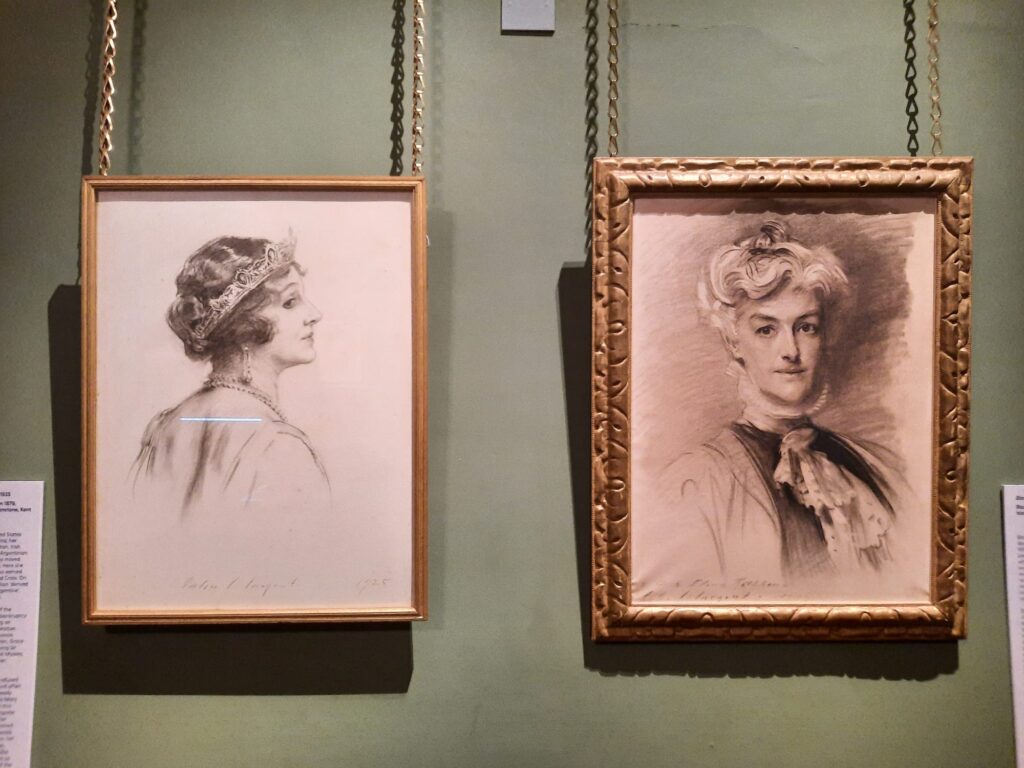

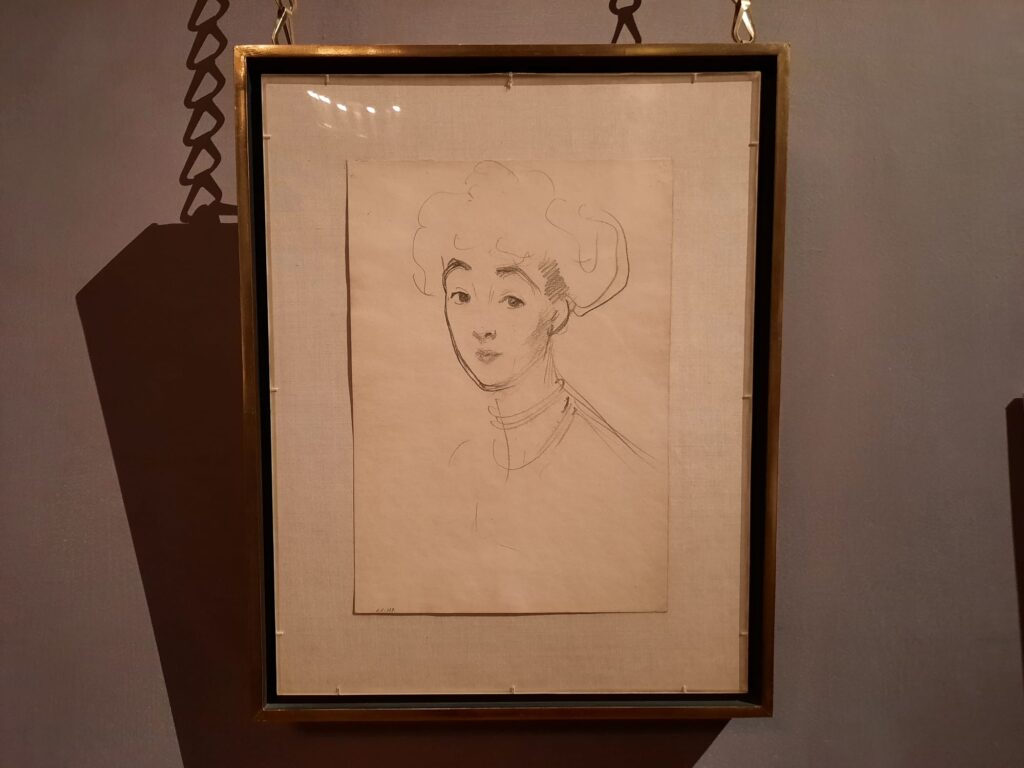

There could hardly be a more appropriate venue for Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits than Kenwood House, itself a former aristocratic summer retreat and a space where status, aesthetics, and inheritance once entwined. The exhibition, which spans just two rooms (the Green Room and the Music Room) is modest in scale. Drawing on major loans and Kenwood’s own collection, the display gathers approximately 18 works by John Singer Sargent, the pre-eminent portraitist of the Gilded Age. These include full-length oils and charcoal drawings, which collectively offer a nuanced reading of the American women who married into the British aristocracy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Kenwood’s own Daisy Leiter, later Countess of Suffolk, is a focal point for the exhibition, and the curators wisely use her portrait as a point of continuity between the existing collection and this focused exploration. Many of the works on view are preparatory sketches, and one of the exhibition’s most interesting revelations lies in the comparison between these and the finished paintings (whether on display or referenced in texts). These women were not passive subjects but strategic participants in shaping their images. As sitters, they understood the currency of visibility. A portrait by Sargent was both an artwork and an asset, a claim to cultural legitimacy as well as to beauty.

Sargent’s evocation of earlier masters, particularly Gainsborough and Reynolds, is unmistakable. Whether through clothing or compositional choices, his portraits pay tribute to British artistic heritage while subtly Americanising it. The sitters were not content merely to enter the British aristocracy: they sought to rewrite their place within its iconography.

Dollar Princesses and Divided Loyalties

The term “dollar princess” has long hovered somewhere between flattery and insult. On one side of the Atlantic, these women were seen by some as traitors to the national spirit: exporting fortunes hard-won by industrial or mercantile means in exchange for foreign titles and often decaying estates. On the other, many regarded them with suspicion. Here were social interlopers lacking pedigree and failing, in some cases, to produce the next generation of heirs. The tension was social, but it was also economic, cultural, and existential. These marriages represented both a transfer of capital and a form of cultural colonialism. America remaking Britain in its own, shinier image.

This exhibition – the first major loan exhibition at Kenwood in a generation – begins to challenge these assumptions. Rather than treating its subjects as avatars of social mobility, it restores them as individuals with agency and complexity. The portraits and accompanying captions exude glamour, but also candour, strength, and at times, even weariness. Anne Breese (later Lady Innes-Ker)’s love for dancing. Nancy, Viscountess Astor in her ‘political uniform’, designed to discourage press coverage of her outfits. A look of defiance in the sketch of Adele Beach Capell, Countess of Essex (née Adele Beach Grant). Sargent captures not just ornamentation but performance.

What emerges is a vision of women who, while certainly beneficiaries of their circumstances, were also deeply aware of the role they were being asked to play and who sought, within the constraints of society, to direct their own narratives.

Gilded Glances, Lasting Impressions

In the interplay of sketch and canvas, and between sitter and artist, Heiress reveals itself as more than a collection of pretty portraits. It is a study in self-invention and soft power, filtered through the brush of a man who understood both with astonishing fluency. Sargent’s great gift was not just technical brilliance but an ability to visualise identity as something fluid, constructed, and aspirational. In that sense, his subjects were thoroughly modern.

The exhibition succeeds particularly well in the intimacy of its presentation. While it might surprise visitors expecting a bigger retrospective, its tight focus is in many ways a strength. In two rooms, visitors move not through chronology but through biography, through the evolution not just of style but of self-presentation. These women in beautiful dresses are symbols of a moment when gender, money, class, and nationalism collided in the drawing rooms of Europe and the canvases of a transatlantic master.

Kenwood House has always invited its visitors to consider the intersections of taste and wealth. In Heiress, those themes are distilled into living, breathing portraits of women who, a century later, still command the room.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Heiress: Sargent’s American Portraits on until 5 October 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.