Kenwood House, London

A first-time visit to Kenwood House turns into an unexpectedly rich day out, combining historic architecture, a world-class art collection, and Hampstead’s landscape history

A Day Out at Kenwood House

A recent bank holiday brought the perfect excuse for a day out, and Kenwood House did not disappoint. In fact, it turned into such a full and fascinating visit that it will take not one, not two, but three posts to do it justice.

First up, Kenwood House itself. A glorious former summer residence perched on the edge of Hampstead Heath, now home to a world-class art collection. Then there was a temporary exhibition which was the reason for visiting now, and which deserves its own post. And finally, I followed a walk tracing the route of the River Fleet, which has one of its sources right on the Kenwood lawn. You’ll be reading the first of these posts today.

Kenwood had been on my list for a while. I’m especially intrigued by the English Heritage model, where many historic houses are open to the public for free. It’s the same with Marble Hill in Twickenham. In both cases, the result is remarkably generous. You can walk in and explore architecture, interiors, and art collections of serious quality, all for the price of a TfL fare.

Kenwood was an escape from the heat and noise of the city. Today, it offers a space to reconnect: with history, with art, and with the open landscape. It’s a clever reimagining of what a country retreat can be.

A House with a History

Hampstead, once a spa retreat far above the city’s summer stinks, has long been a haven for those seeking respite from London’s heat. In previous posts, I’ve explored Keats House and Burgh House, both testaments to this legacy.

Kenwood House’s origins trace back to the early 17th century. In 1616 John Bill, King James I’s printer, purchased the estate and likely constructed the initial brick structure. By 1665, the house boasted 24 hearths, indicating its substantial size.

The property changed hands multiple times, with significant modifications around 1700. In 1754, William Murray, later the 1st Earl of Mansfield, acquired Kenwood. A prominent barrister and judge, Murray served as Lord Chief Justice from 1756. Between 1764 and 1779, he commissioned Scottish architect Robert Adam to remodel the house into a neoclassical villa. Adam’s designs, including the iconic library and entrance portico, are among his finest surviving works.

One of Kenwood’s most fascinating historical figures lived here in the late 18th century. Dido Elizabeth Belle was the daughter of a formerly enslaved African woman and Captain Sir John Lindsay, a Royal Navy officer and nephew to Lord Mansfield. Born in 1761, Dido was raised at Kenwood alongside her white cousin Lady Elizabeth Murray. Her presence in the household was highly unusual for the time. She was educated, brought up as a gentlewoman, and played a visible (though ambiguous) role in domestic life. Her life challenges common assumptions about race, status, and family in 18th century Britain. And may also have influenced Mansfield’s legal views on slavery, particularly in the landmark Somerset v Stewart case of 1772.

The estate remained with the Mansfield family until the early 20th century. In 1922, the 6th Earl sold many of the house’s furnishings, and by 1925, the property faced potential redevelopment. Salvation came when Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh, purchased Kenwood and its grounds for £107,900. A philanthropist and member of the Guinness brewing family, he bequeathed the house and his art collection to the nation upon his death in 1927. Not entirely altruistic, though: this was a bit of NIMBYism as Edward didn’t fancy a load of new homes on the Kenwood grounds as neighbours.

Today, Kenwood House stands as a testament to centuries of architectural evolution and benevolent preservation. Its history, from spa retreat to neoclassical masterpiece, offers a window into London’s, and Hampstead’s, rich history.

The Visitor Experience

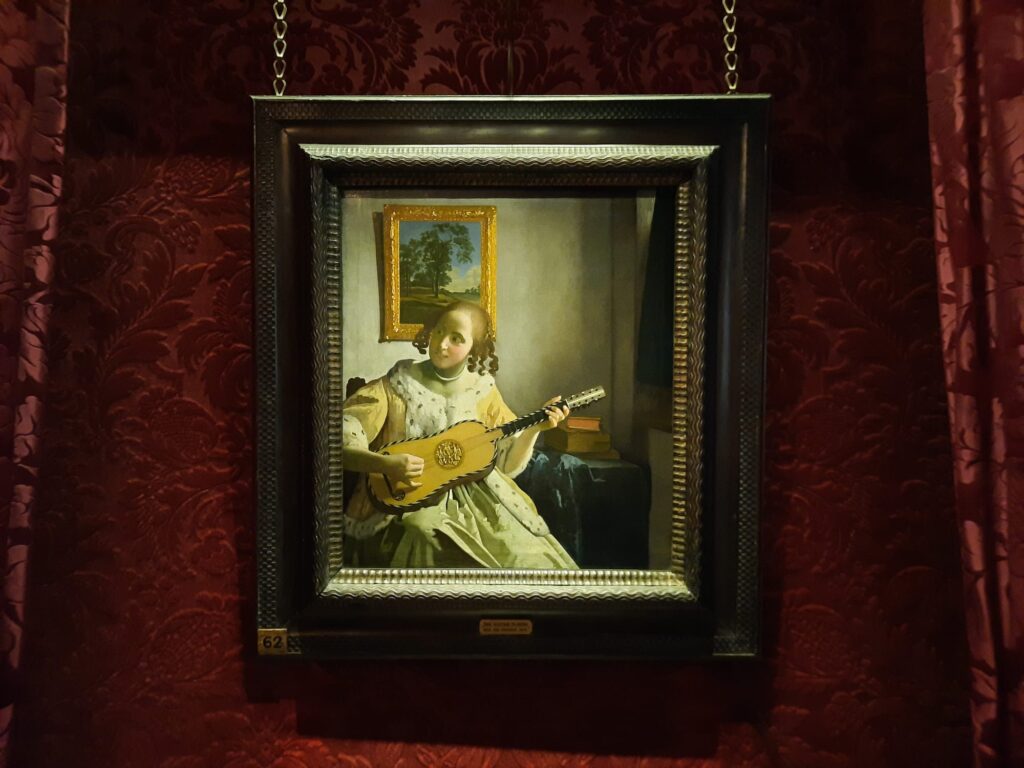

You don’t often find yourself blinking at a painting and wondering, “Hang on — is that a real Vermeer?” But that’s exactly what happened to me in one of Kenwood House’s beautifully lit rooms. And it turns out it is real. The Guitar Player (c.1672), one of only 34 known works by Johannes Vermeer, hangs here quietly. No crowd barriers, no special lighting rig, just an extraordinary masterpiece in a Georgian dining room.

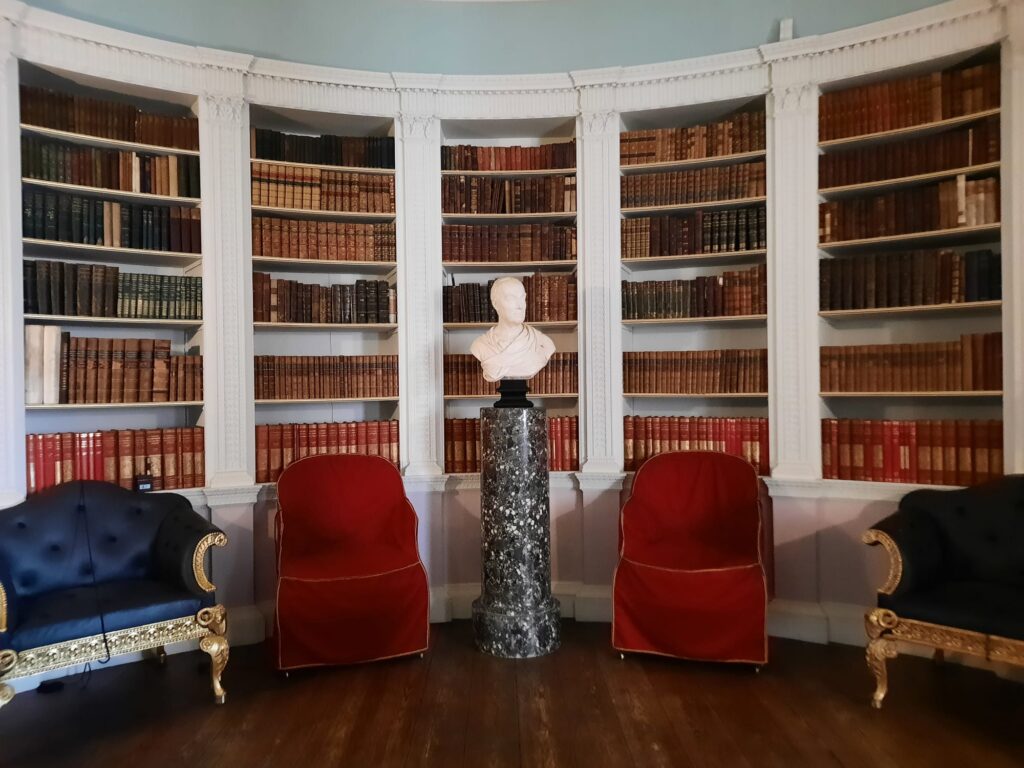

That sense of unexpected calibre runs throughout Kenwood’s art collection. The library, designed by Robert Adam with exquisite plasterwork and a rainbow of pastel tones, is a piece of art in itself. But the paintings are no less impressive. There’s a Frans Hals portrait I recognised from previous exhibitions. And also works by Rembrandt, Turner, Gainsborough, Reynolds, and Van Dyck. The range and quality genuinely surprised me. This is one of the finest collections of Old Master and 18th-century paintings in Britain, and I hadn’t quite realised it was all here, free to view.

Much of this collection was part of the bequest by Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh. His intention was clear: that these great works should be enjoyed by the public, not locked away in private galleries. Since then, English Heritage has added to the collection, including 20th-century works, decorative objects, and collections of things like miniatures and buckles, that help return a lived-in feeling to the historic rooms.

The experience of visiting is enhanced by the guides – who, in my case, seemed to spring into life like wind-up encyclopaedias the moment anyone stepped into the room. Their enthusiasm and depth of knowledge made the house feel both welcoming and richly layered, offering anecdotes and insights.

Finishing the Circuit

Kenwood House turned out to be one of the most pleasant surprises I’ve had in a while. A peaceful wander through handsome historic interiors, and then the quite unexpected bonus of a magnificent art collection. I’d always intended to go, but hadn’t expected to leave thinking I might start recommending it to friends and family visiting London. It’s easy to pair with a walk on the Heath, a stroll through Hampstead Village, or, as in our case, a longer route tracing the River Fleet’s course downhill from its spring near the Kenwood lawn. It all makes for a day that feels both cultural and restorative.

Our visit ended (as many good ones do) with a pause for lunch. Kenwood’s outbuildings are now repurposed as a café and other facilities. While these aren’t quite as lovingly preserved as the main house, they’re an interesting glimpse into the estate’s working past. There’s one last architectural feature worth ducking into before you leave: the brick-walled cold bath, just behind the café. It’s a small, cool reminder (literally and figuratively) of Hampstead’s historic reputation for healthful waters and spa-like escapes.

It’s this sense of continuity, from 18th-century pleasure gardens to today’s picnics on the lawn, that gives Kenwood its charm. Yes, it has grandeur, but it’s also a public space that Londoners can still use much as its original owners did: for air, light, conversation, and the quiet pleasure of a good view.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.