Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting – National Portrait Gallery, London

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting at the National Portrait Gallery – a raw, compelling look at the body, form, and feminist art from one of the UK’s leading contemporary painters.

A First Encounter with Jenny Saville

I was glad to catch this exhibition early in its run (OK, fine, it then took me a little while to schedule this post…). Jenny Saville is an artist I’ve known of for years without ever having a proper opportunity to get to know her work. I’ve written a fair bit on this blog about the Young British Artists – their impact, the brashness of their youth, their moments of brilliance – but Saville has always been on the periphery for me. She’s less in your face. More interested in the body than the brand.

So when the National Portrait Gallery announced Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, I was intrigued. The NPG hasn’t always focused its energy on contemporary painting, or at least not in the exhibitions I’ve attended over the years. But the refurbishment seems to have come with a shift in tone. Recent exhibitions have felt bolder, pushing our expectations of portraiture. The NPG used to feel a bit like the sensible sibling of Tate Britain. Now it feels like it’s trying to hold its own.

The show is arranged across a slightly strange skew of rooms which forms the NPG’s prime exhibition space. And it’s the first chance in the UK to see this many Saville works in one place. You move through the exhibition slowly, partly because the works demand it. These are big paintings, physically and emotionally. Not ones you can just glance at before moving on. There’s a depth to them that reveals itself gradually: the way a muscle shifts beneath skin, or the trace of a gesture left in paint. It’s not often I feel like I’m seeing someone’s work properly for the first time. But that’s what this visit felt like. A nice reminder that art can always find a way to surprise you.

Jenny Saville

Jenny Saville has always sat in a slightly unusual place in the story of the YBAs. Technically, she was part of that group, as she was included in Sensation in 1997, alongside Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin and the rest. But she didn’t study at Goldsmiths, didn’t go in for the media stunts, and didn’t move in quite the same circles. Her training was at the Glasgow School of Art, and her breakout moment came when Charles Saatchi saw her degree show and offered to buy everything. It was the early 1990s. He gave her a studio and effectively commissioned her next body of work.

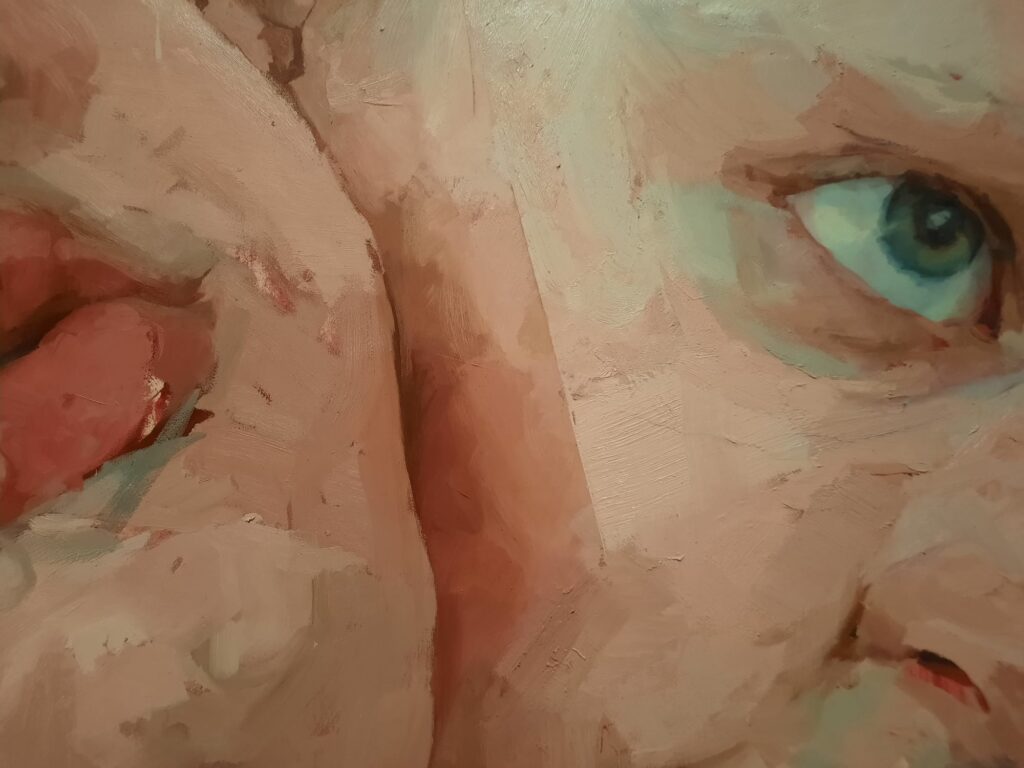

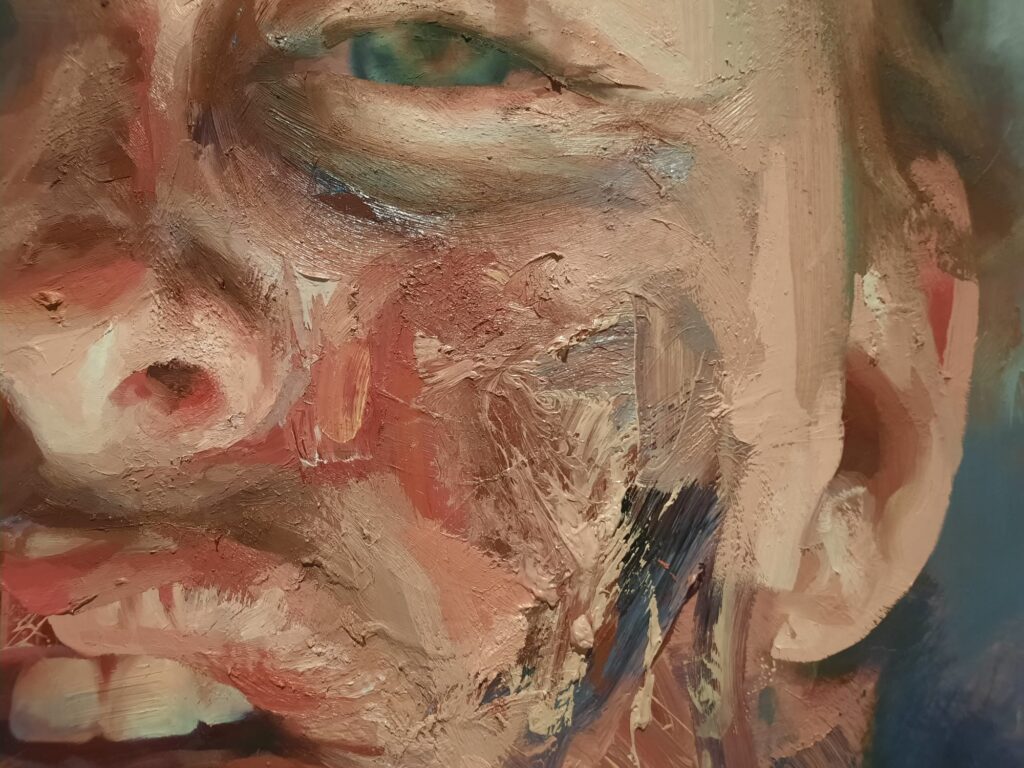

What makes Saville stand out from the others, then and now, is her deep commitment to painting. At a time when the YBAs were exploring installation, video and conceptual tricks, Saville was looking at Titian. At Rembrandt. And at anatomical drawing and medical photography. You can trace the influence of Francis Bacon in the way she distorts bodies, but also of Rubens in the solidity of flesh. She’s interested not just in the surface of the skin, but the substance of human bodies. Vessels that hold weight, memory, and feeling.

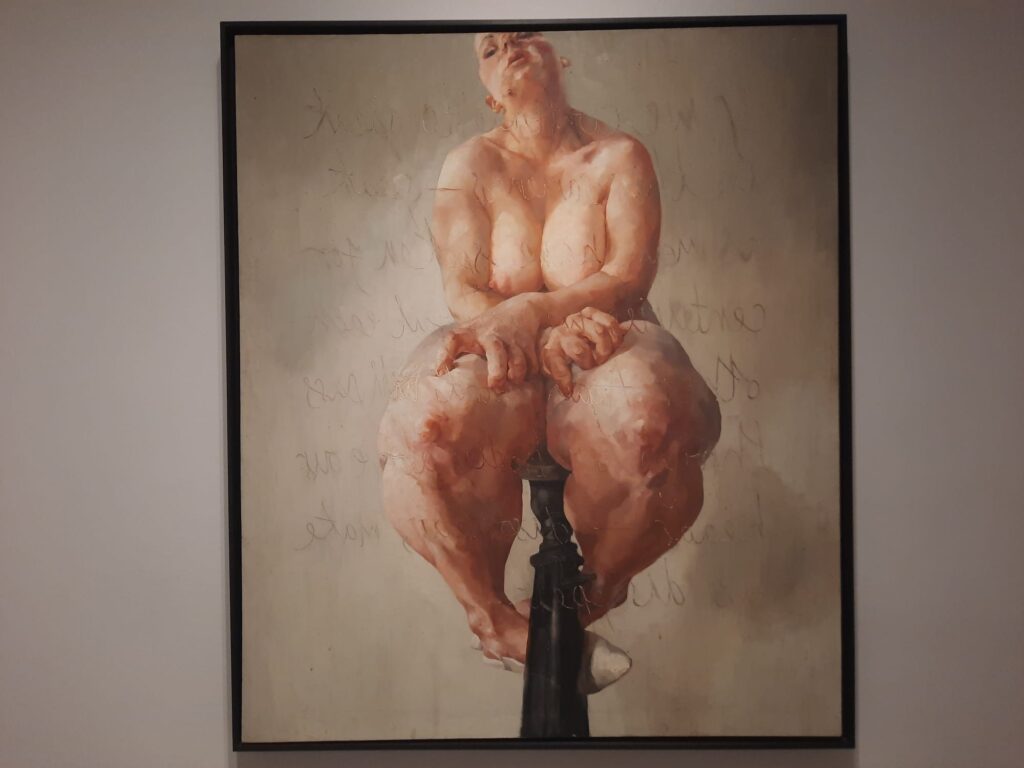

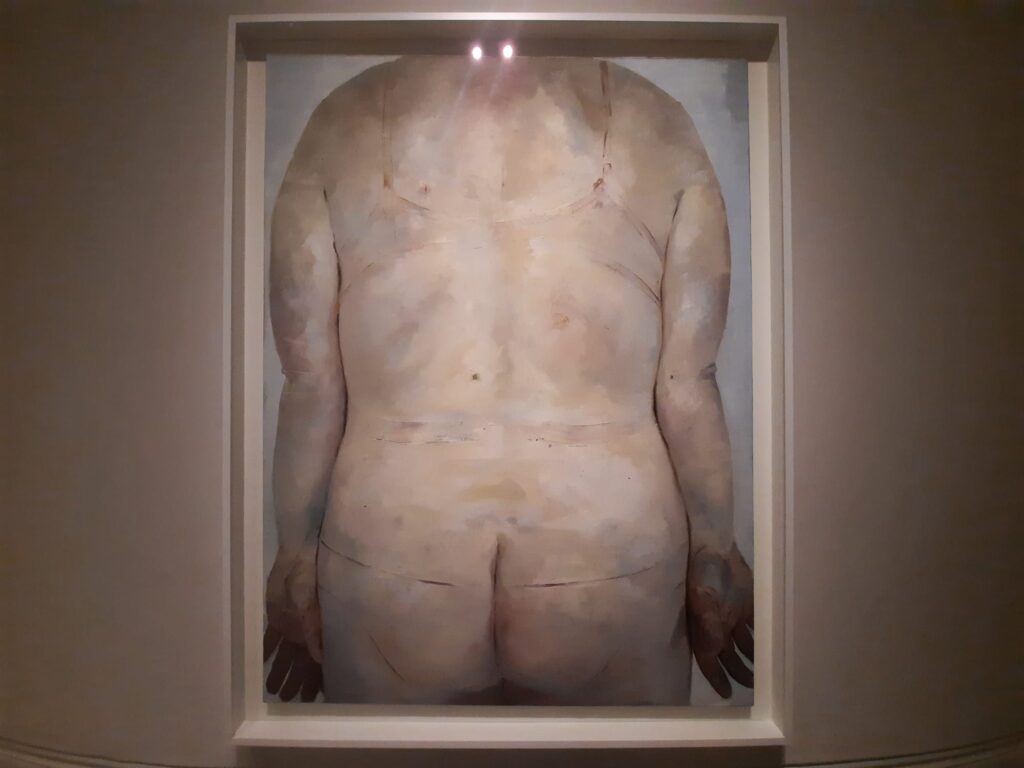

There’s also a quiet, persistent feminism to her work. Again not in a slogan-heavy way. Instead, she paints women’s bodies as they really are. Not idealised, not eroticised, not objectified. There’s fat and muscle, bruises and scars. There’s pregnancy, disability, ageing: the full range of human experience. In a way, she’s more traditional than some of her peers, and more radical at the same time. She brings painting back to its oldest subject, the human figure, and insists we really see it.

Flesh and Form

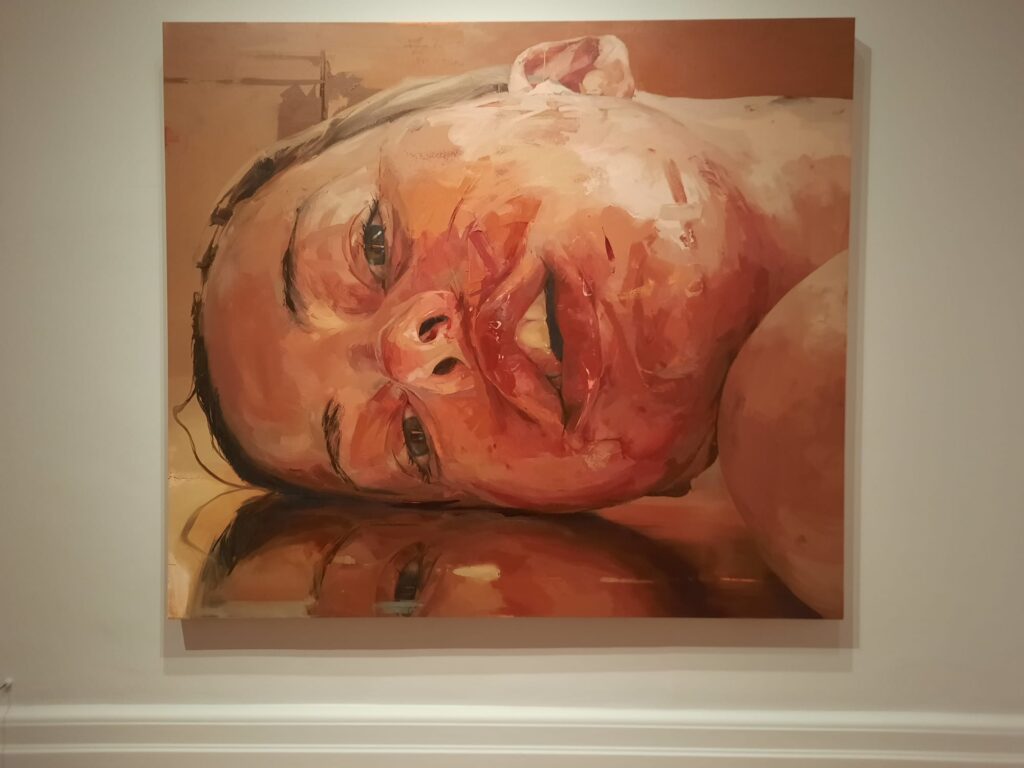

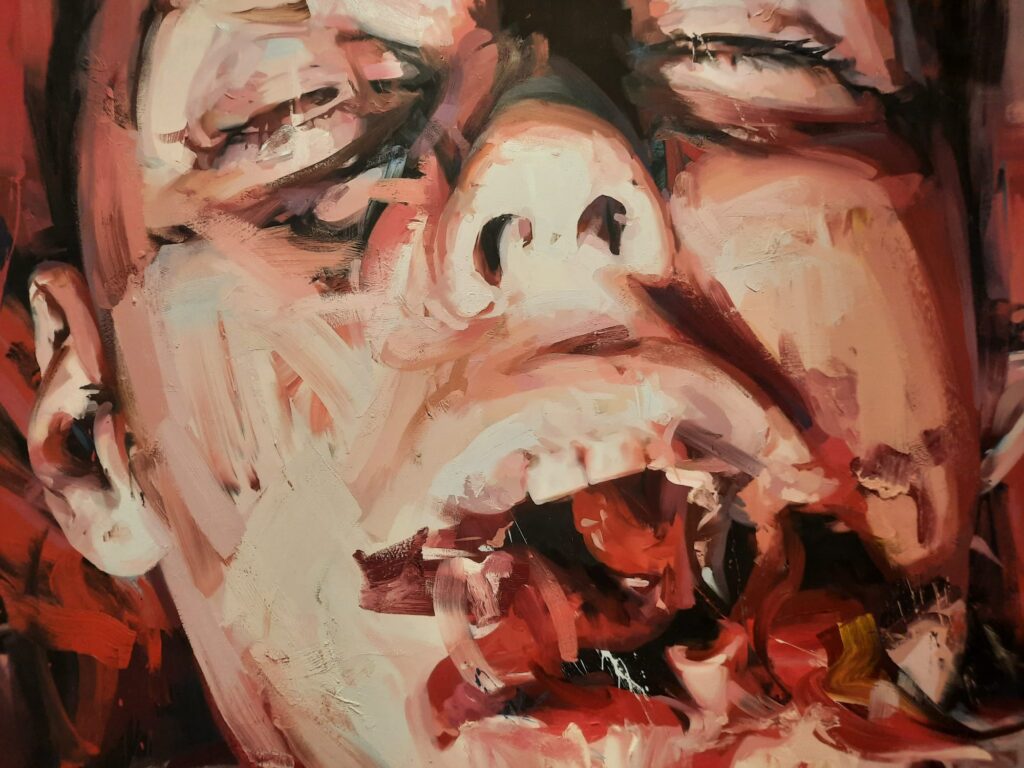

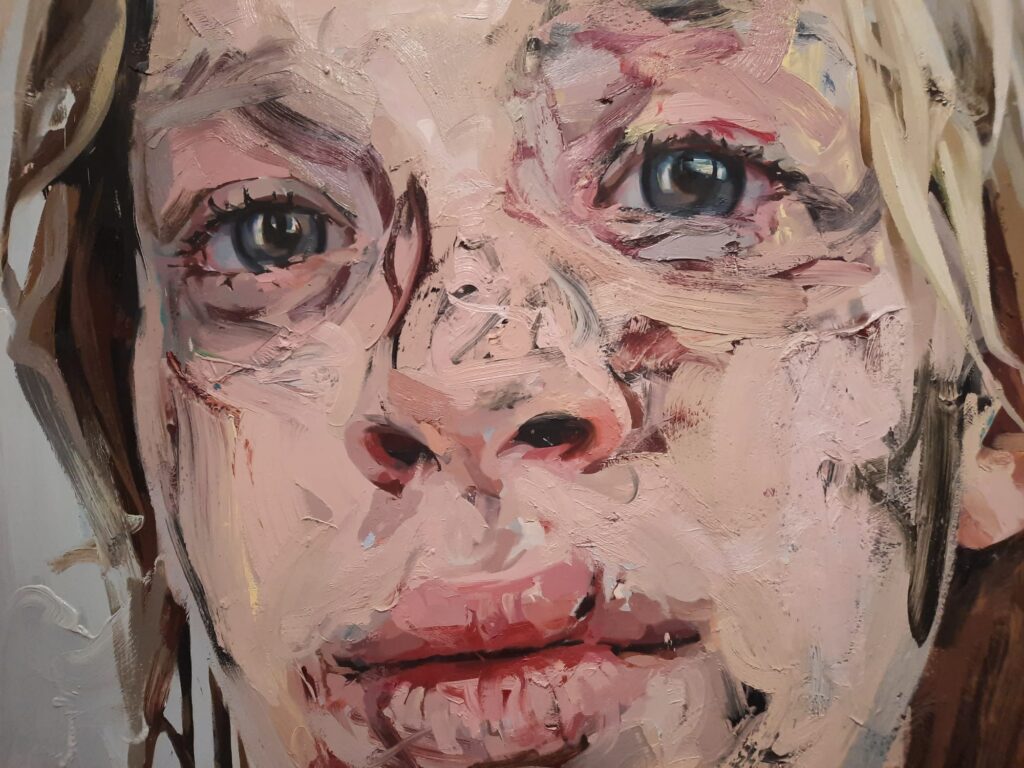

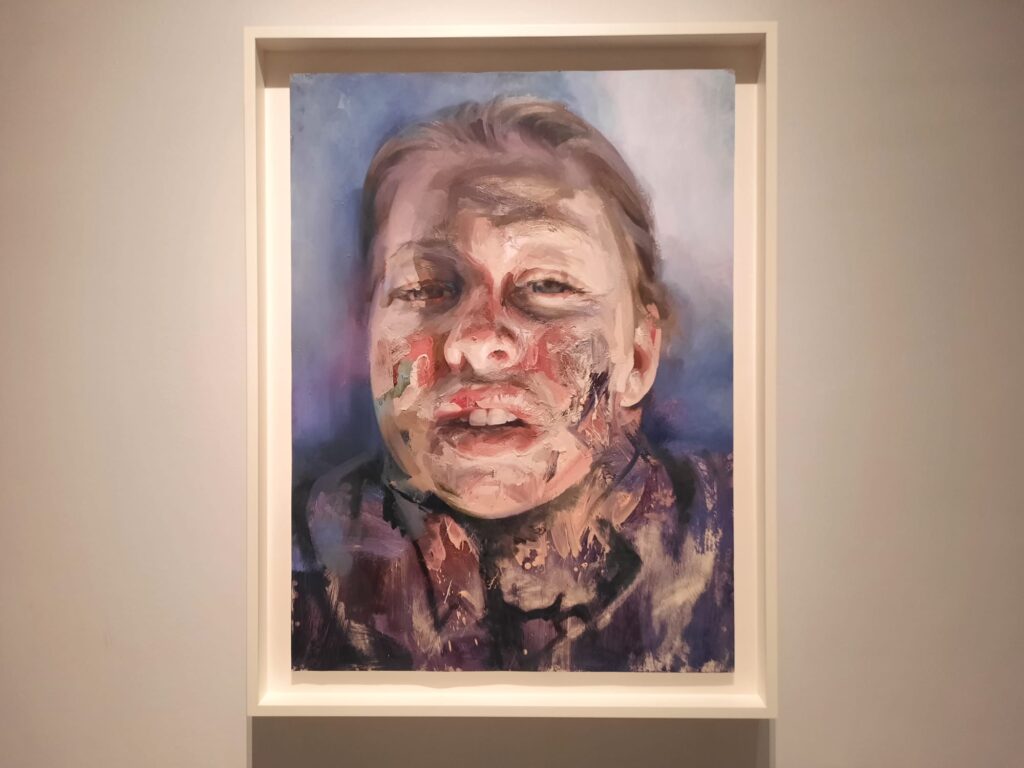

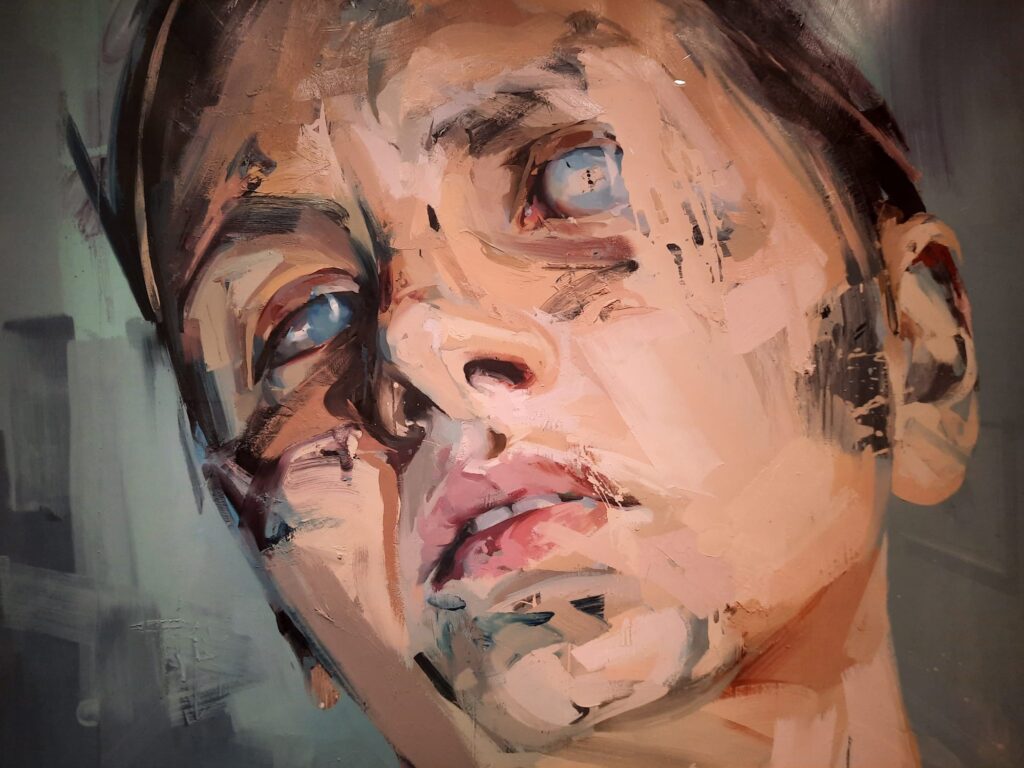

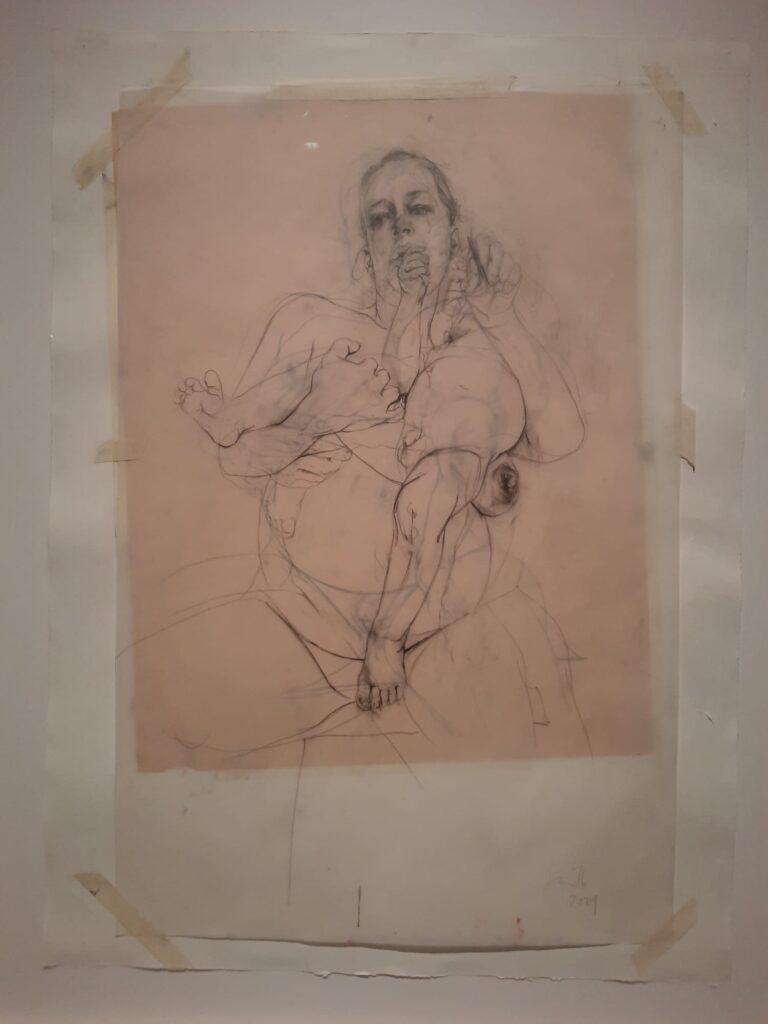

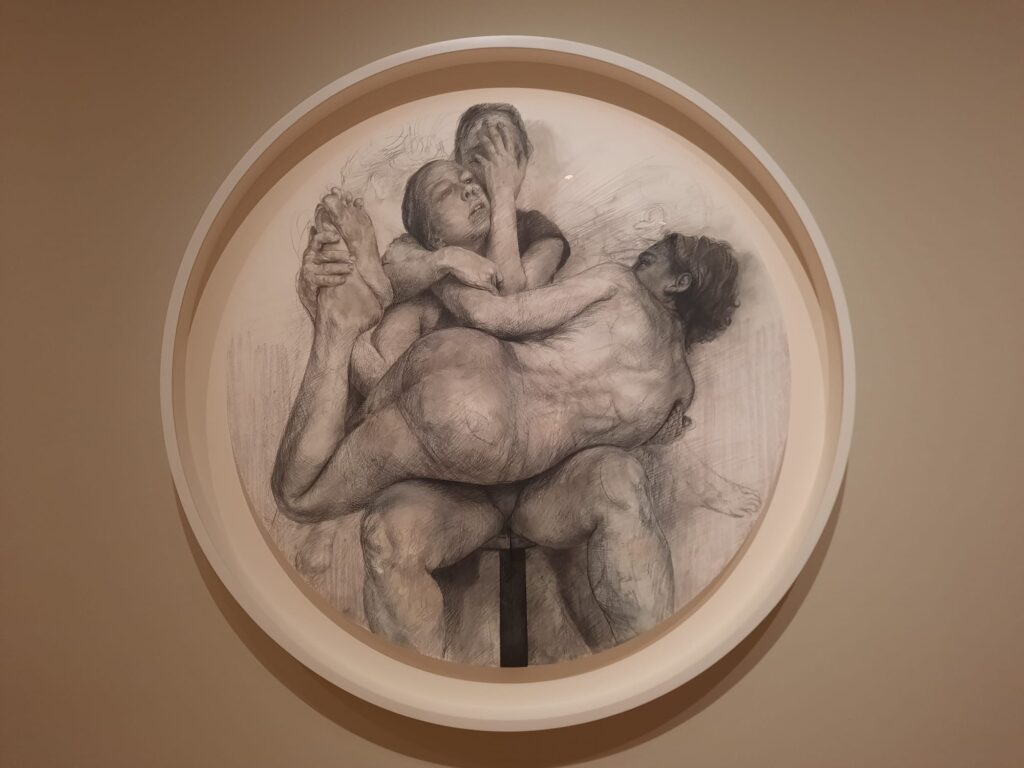

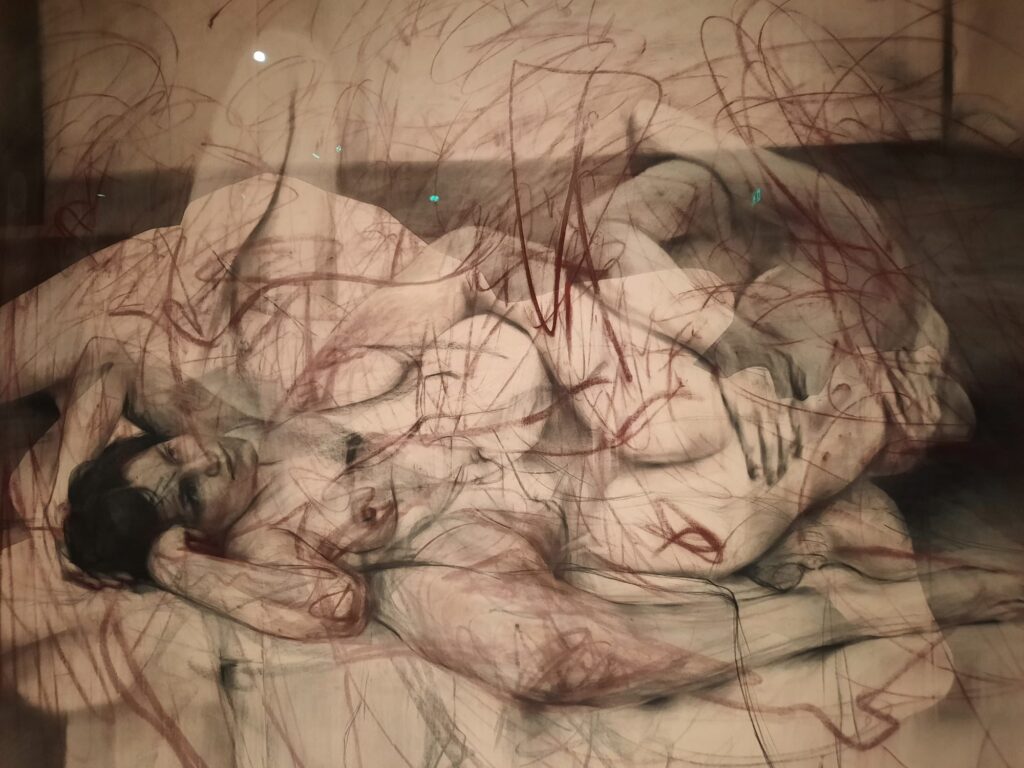

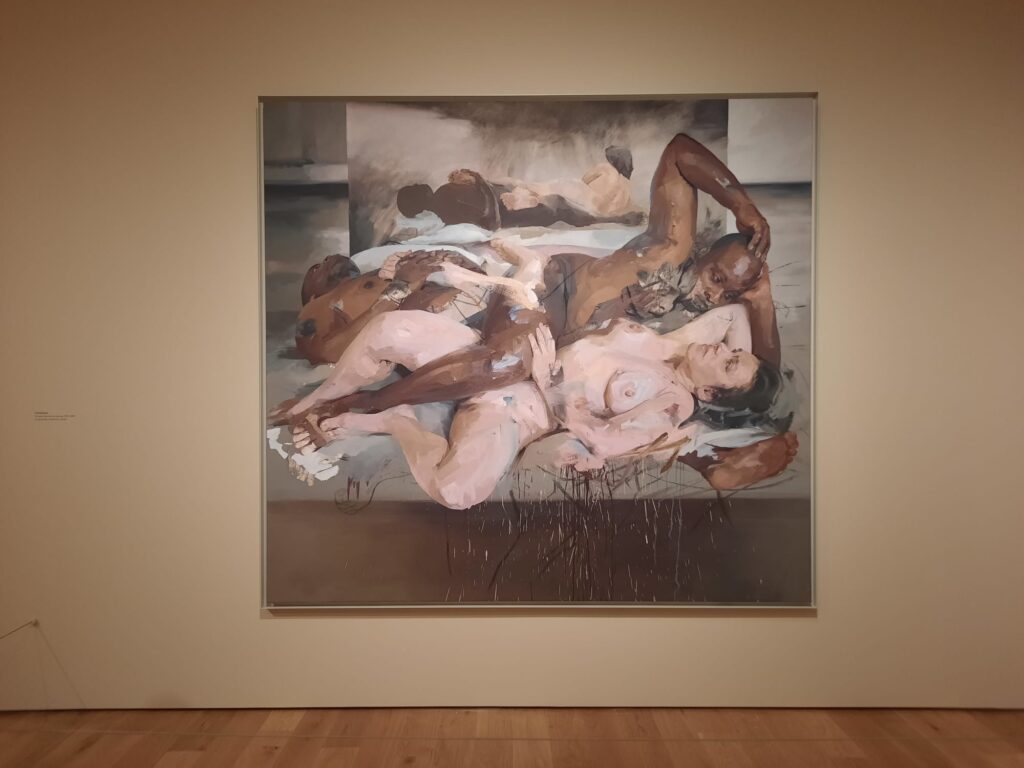

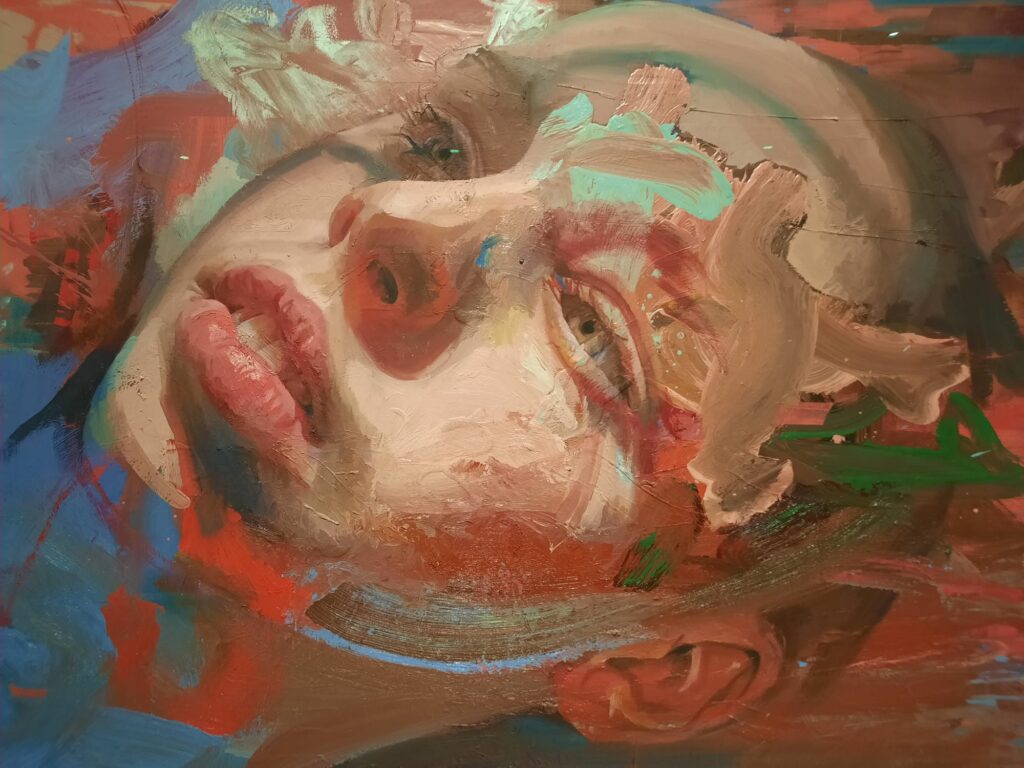

The human body is the thread winding through this exhibition. Every canvas contains one, or a part of one. But the variety across the works is striking. Some figures are huge, looming from the wall in rough, thick paint. Others are translucent, worked in graphite or pastel, the lines worked and reworked. There are babies, pregnant bellies, twisted limbs. Bodies alone and bodies tangled. Bodies that shift between states.

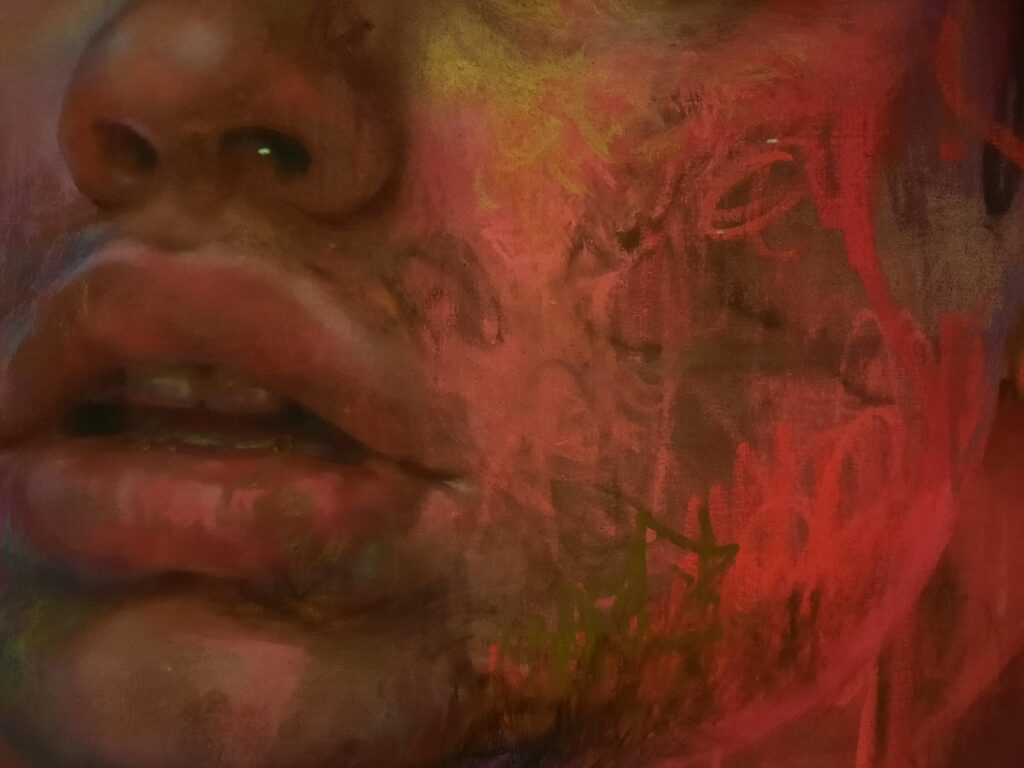

Colour plays a huge role. In some works, Saville uses a rich, earthy palette (deep reds, purples, and ochres) that makes the flesh feel warm and real. Elsewhere, she pares it back to greys and whites and subtle pinks, so that the body becomes almost sculptural. One figure might feel like it’s emerging from a block of stone, another as if it’s dissolving into air. Despite the physical scale of the works, they often feel surprisingly tender.

There are moments that nod clearly to art history. We get reworkings of classical poses and shapes: a pietà, reclining nudes, even a tondo. But none of them feel like homage for its own sake. Saville has brought these traditions into the contemporary era. It’s a body of work that places her in conversation with centuries of figure painting, but makes it her own.

Some of the most moving pieces are the quieter ones. Paintings where tension is absent from the face, eyes half closed, the body at rest. In a moment where most artists might reach for drama, she opts instead for truth. And it’s that which draws you in. Especially when the result is unflinching or unsettling. What ties the exhibition together is Saville’s unwavering attention to what it means to exist in a body.

Letting the Work Speak for Itself

There’s a timeline, tucked in early on, tracking key biographical moments and encounters with art history. And some individual works get labels explaining technique or context. But what’s striking is the lack of heavy curatorial intrusion. There are no grand thematic separations, no big wall texts telling you how to feel or what to think. The exhibition allows the paintings to do the work.

This suits Saville’s practice. Her paintings resist neat categories. They are studies in complexity: of surface, of flesh. It’s not that there’s no consistency. There is, as we’ve discussed already: the human body. But the way it’s approached shifts dramatically from work to work. In some, colour is stripped right back. In others, the paint is wild and hot and close to abstraction. We move between quiet observation and theatrical intensity.

Letting the works hang together without overstating the connections means you notice those connections yourself. A hand here, mirrored in a different pose three rooms on. A certain brushstroke. The odd cropping of a figure. There’s space to look closely and draw your own conclusions. It’s a different kind of intimacy. Not just with the subjects (though many of them, in their wide-eyed gazes, are very compelling) but with Saville as a painter. You begin to see how much looking is built into the work. How many decisions go into every mark. The physicality of it. The commitment. It’s a rare thing, to feel both completely in the artist’s world and completely left to your own devices. Ultimately, that is the success of this exhibition.

Final Thoughts

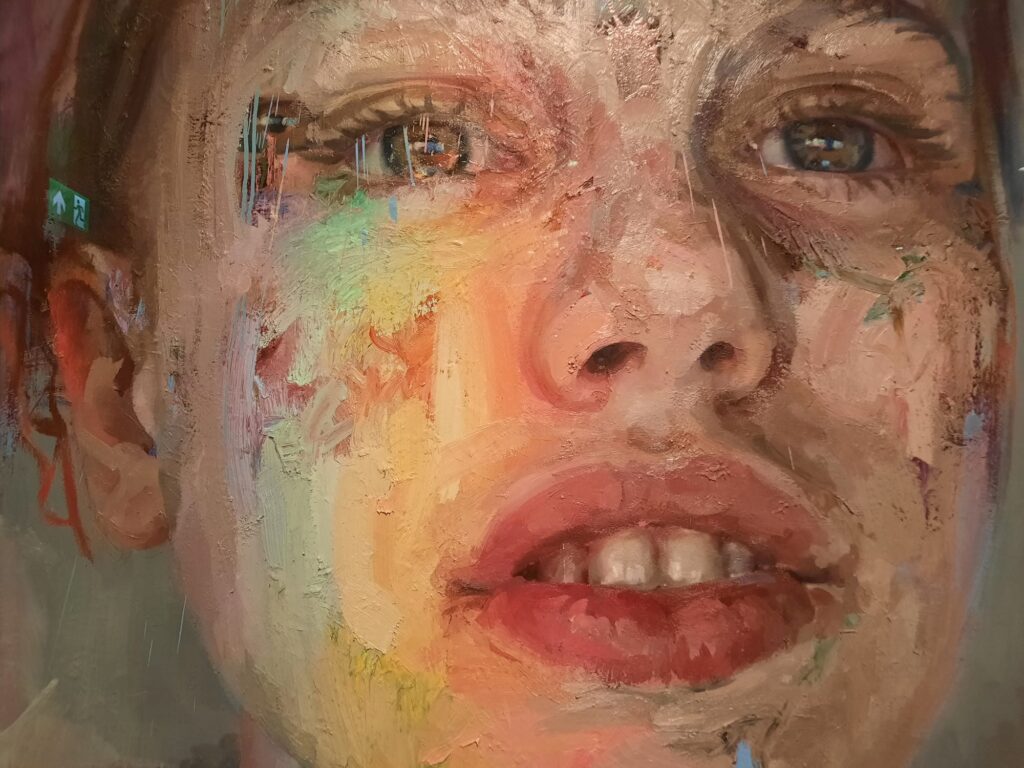

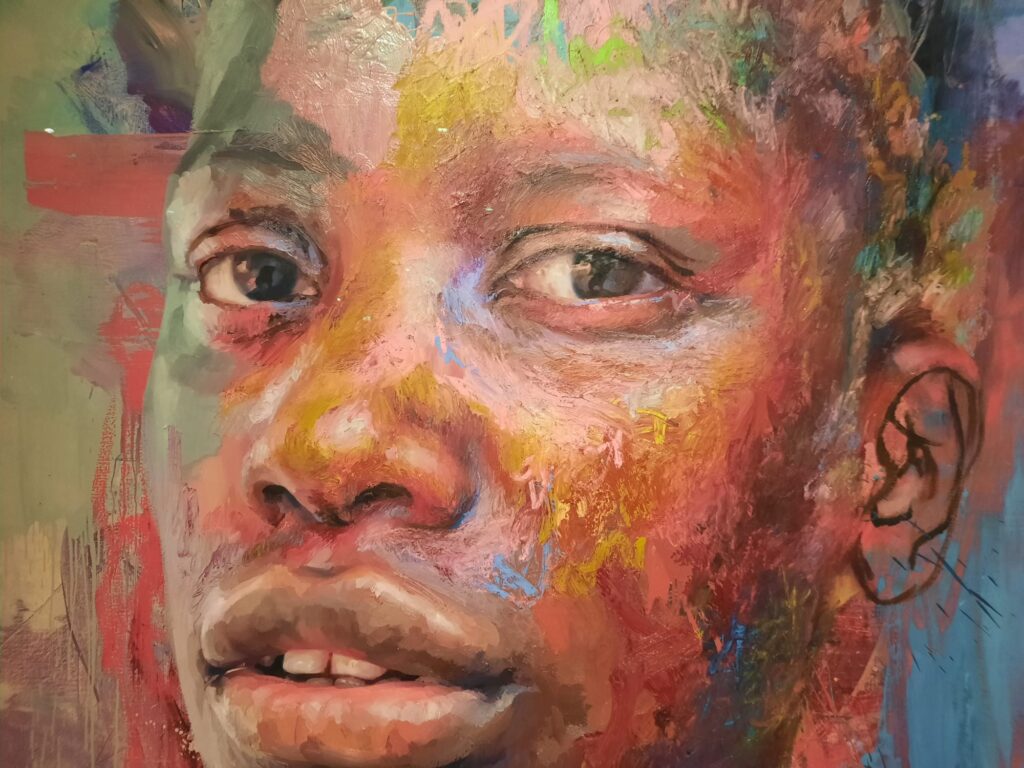

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting is a show that stays with you. The works in the last room are among the most powerful: large canvases, often close-cropped, with explosive colours, neons and refracted light dancing over faces. You feel their weight, the drag of skin, their youthfulness and yet the slight imperfections of their humanity.

Saville’s great strength, I think, is how she allows us to grasp that reality. The imperfection, the ambiguity, the tension between presence and privacy. Many of her subjects look away, or close their eyes, or seem lost in thought. But they don’t feel distant. There’s an intimacy here that doesn’t rely on performance. She invites us to notice people not when they’re posed or poised, but when they’ve let themselves go. Tension dropped from the face, muscles relaxed, just being. It’s oddly vulnerable, and totally captivating.

It’s also striking how ordinary these bodies are. Not in the sense of boring (far from it), but in the sense that they are recognisable. Flesh with scars and creases. Bodies that don’t fit conventional ideas of beauty or form. Disability, fatness, pregnancy, sex. It’s all here, painted with tenderness and rigour. And in doing so, Saville opens space for a bigger conversation about how bodies are seen. And how they see themselves. For those who know Saville’s work well, this exhibition deepens the picture. For those who are, like me, less familiar, it’s an intense and impressive introduction.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting on until 7 September 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.