Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry – Le Château de Chantilly

A once in a lifetime exhibition, this is your chance to see Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, the Mona Lisa of manuscripts.

A Once in a Lifetime Exhibition

“What is aura? A peculiar web of space and time: the unique manifestation of a distance, however near it may be. To follow, while reclining on a summer’s noon, the outline of a mountain range on the horizon or a branch, which casts its shadow on the observer until the moment or the hour partakes of their presence—this is to breathe in the aura of these mountains, of this branch. Today, people have as passionate an inclination to bring things close to themselves or even more to the masses, as to overcome uniqueness in every situation by reproducing it. Every day the need grows more urgent to possess an object in the closest proximity, through a picture or, better, a reproduction. And the reproduction, as the illustrated newspaper and weekly readily prove, distinguishes itself unmistakably from the picture. Uniqueness and permanence are as closely intertwined in the latter as transitoriness and reproducibility in the former.”

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/1137367-what-is-aura-a-peculiar-web-of-space-and-time

Walter Benjamin, A Short History of Photography, 1931

To begin with, it’s important to understand that I am very much a Benjaminian when it comes to art. I don’t care how good your reproduction is, I want to see the original.* I’ve flirted with immersive experiences and VR, and enjoyed them, but for me these media would be but poor substitutes for actual artworks.

And so, the first time I went to the Château de Chantilly, I sighed a little in disappointment when, as expected, they had a high fidelity facsimile of Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry on view instead of the original. I know how fragile manuscripts can be, and how little they can cope with permanent exhibition. But a woman can hope.

And so imagine how pleased I was when I saw there was going to be a temporary exhibition at the château putting this treasured work on display. It was encouragement enough for me to follow the Château de Chantilly website even more assiduously, book tickets once they went on sale, and make plans to spend a weekend in Chantilly. I’ve described that weekend in my last post. But today I’m going to tell you all about the exhibition that took me there.

*Interestingly, this is much less the case for the Urban Geographer. Many’s the time he’s expressed being underwhelmed by a place or experience because he’d already seen a photograph.

What’s the Big Deal?

Even if you’re not familiar with the name Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, you might have seen an image of it. It’s a famous medieval manuscript, which the exhibition describes as the ‘Mona Lisa’ of the genre. But let’s break down what it’s all about.

Le Duc de Berry. I’m going to start here, rather than explaining a book of hours just yet. Jean de Berry, or Jean le Magnifique, was born in 1340. He was duke of Berry and Auvergne, Count of Poitiers and Montpensier, brother to King Charles V of France, and regent of France for his nephew Charles VI. He was born at the Château de Vincennes, spent some time in England as a hostage, was bold in his politics, but more conciliatory in later years.

However, today he is best remembered as an art patron. He might not have thought of it as art, though (although he clearly wanted the best of the best): Jean was commissioning manuscripts in a religious context. And some works in gold and precious metals and jewels. Regardless, he died deeply in debt thanks to his artistic patronage so took it very seriously. As well as a couple of the gold objects, a number of manuscripts he commissioned survive to today.

A Book of Hours. A book of hours is a type of religious tool popular in the Middle Ages. It helped its owner to fulfil their religious obligations by tracking the canonical hours during the day, and the calendar of religious feasts. It evolved from the earlier psalter, and breviary. Many books of hours belonged to women, being given as gifts from husbands to wives at the point of marriage. And we should remember that, given that their production was an entirely manual process, books of any kind were rare and precious objects. Jean de Berry had a remarkable library, in that he owned about 300 books. In the 14th century it became fashionable to use books of hours as vehicles for lavish illustration.

Les Très Riches Heures. Le duc de Berry owned 6 psalters, 13 breviaries and 18 books of hours. He commissioned six of these, and presumably purchased the rest. Several of the books have become known by their names in 15th century inventories, such as le Psautier du duc de Berry, les Petites Heures du duc de Berry, or, most crucially, Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry.

But Why is it the Mona Lisa of Manuscripts?

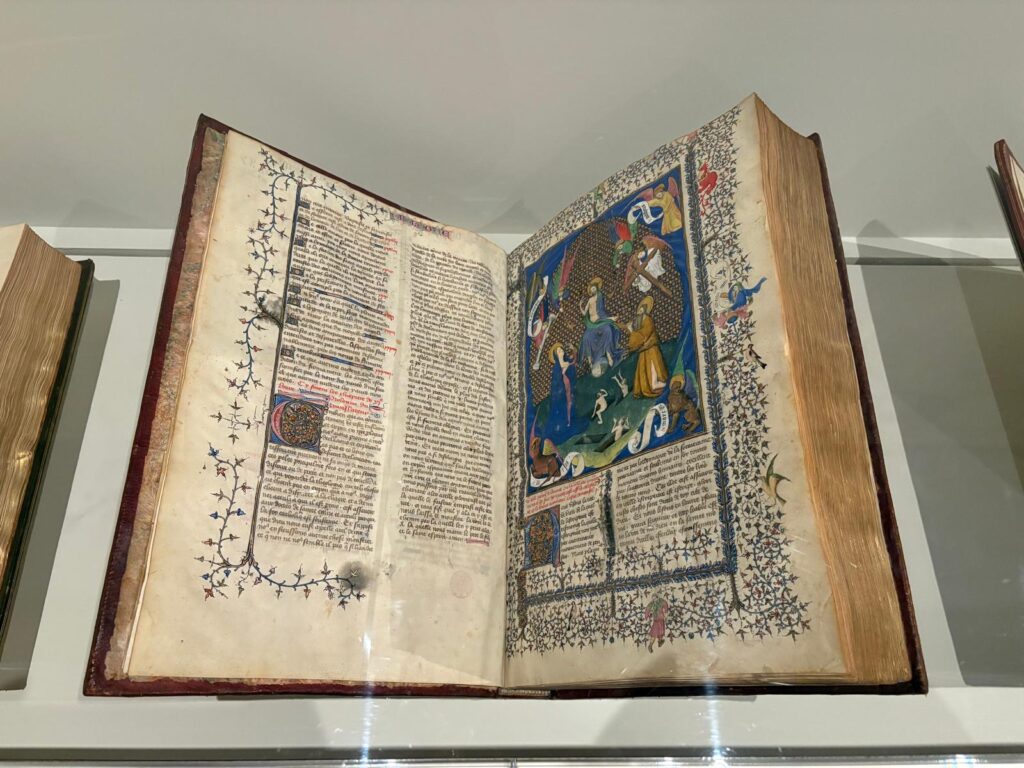

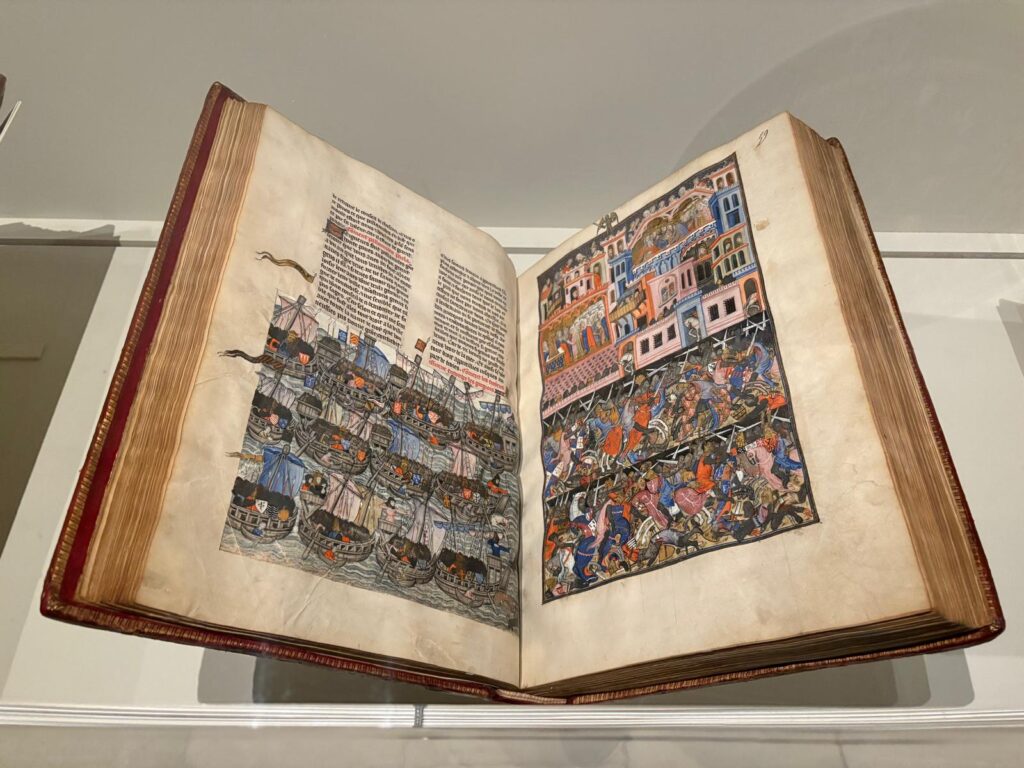

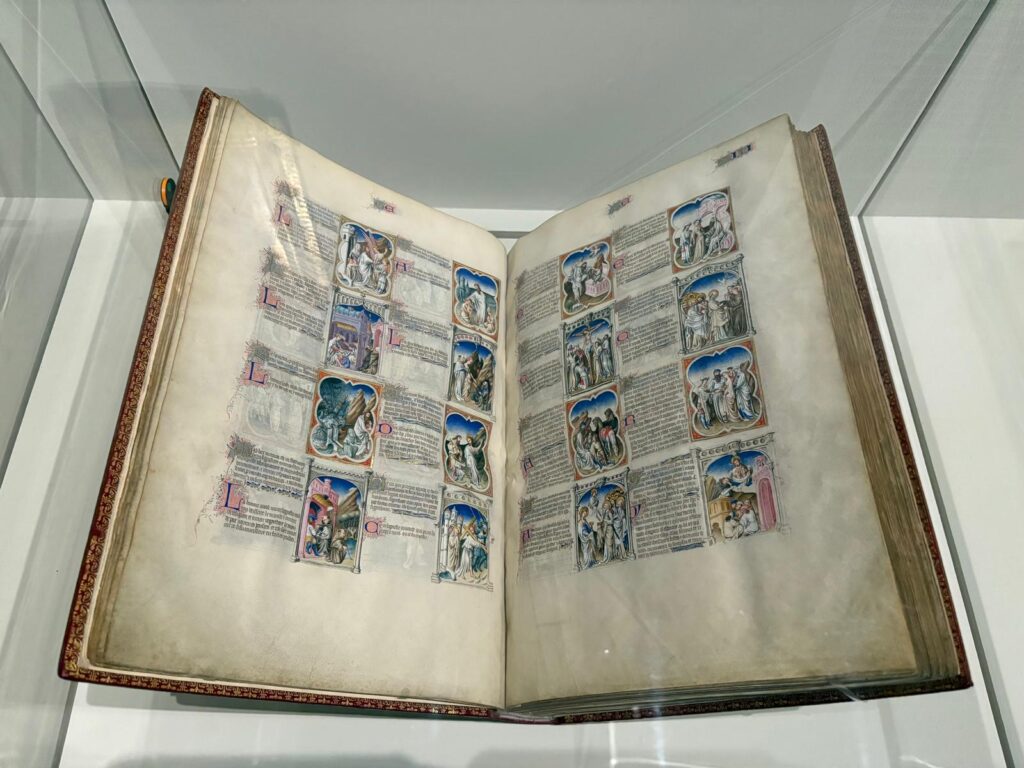

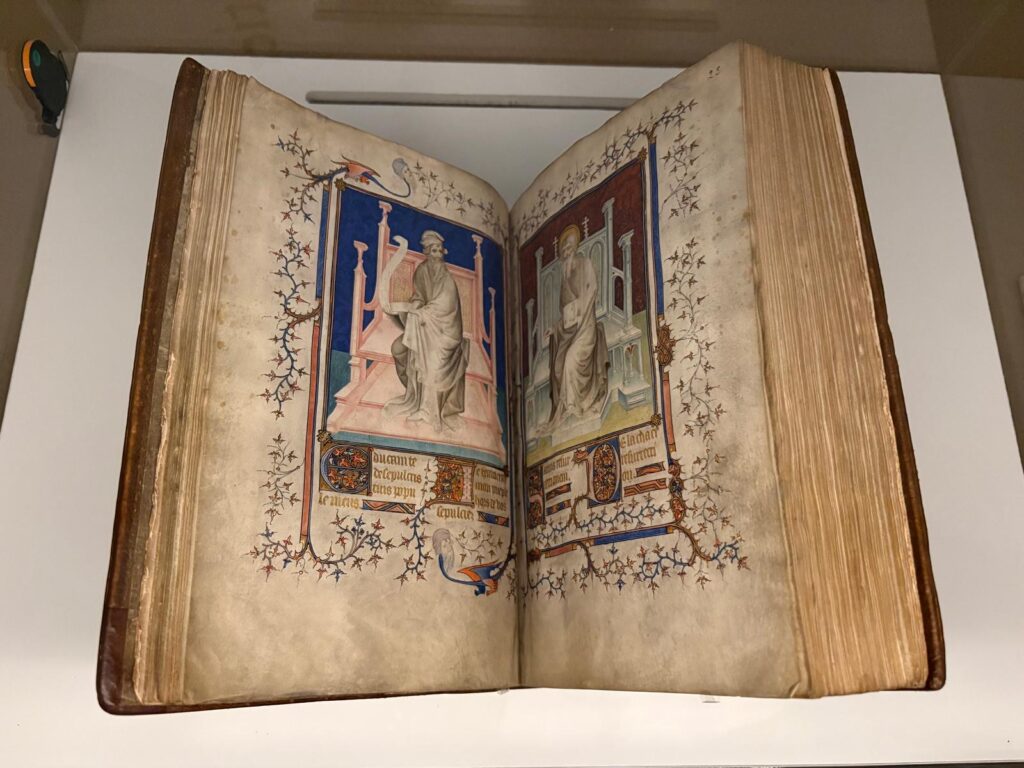

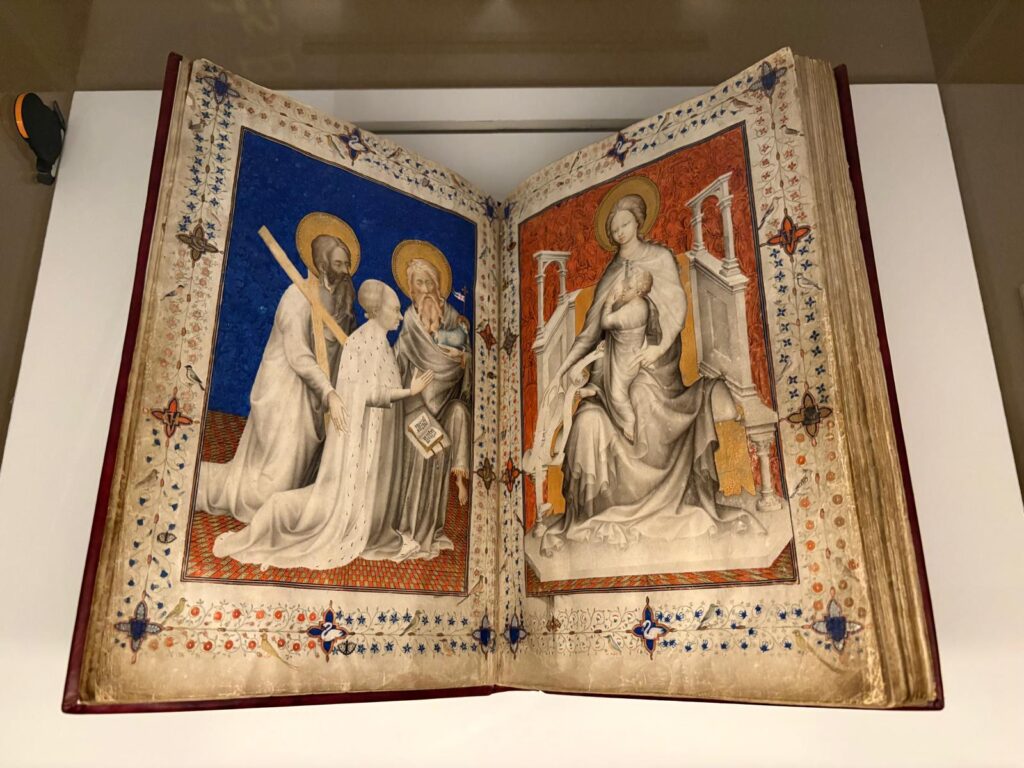

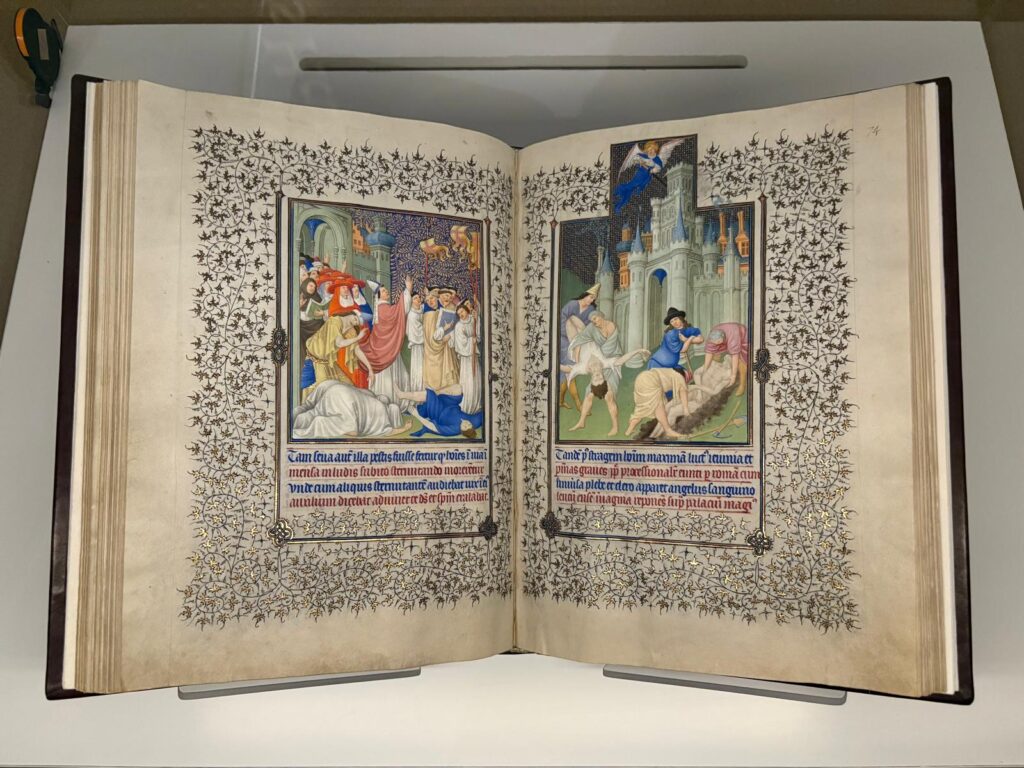

Well that comes down to who Jean de Berry commissioned to do the work. In this case, the Limbourg brothers, Paul, Johan and Herman. We know it was them because of a note in one of the inventories. The Limbourg brothers worked on the manuscript between 1412 and 1416. They’d already illustrated Les Belles Heures de Jean de Berry, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection. Each manuscript Jean commissioned seems to have pushed the boat out further, however. Over a total of 206 leaves, Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry contains 66 large miniatures, and 65 small ones, many more than would usually be seen in a manuscript of this size.

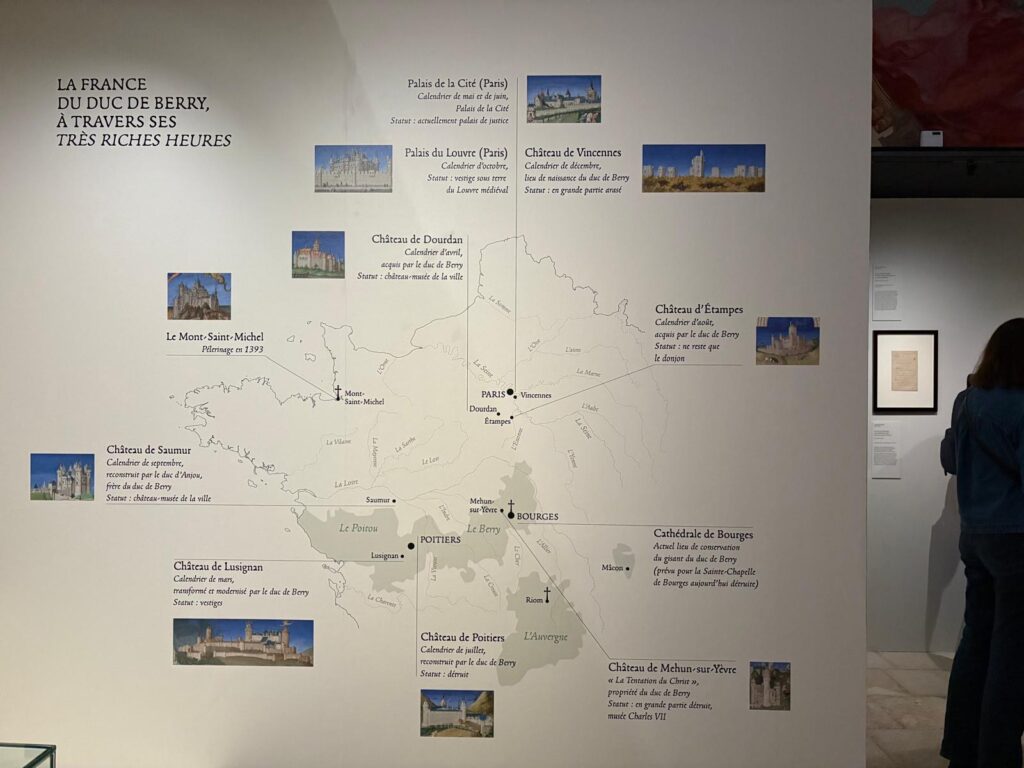

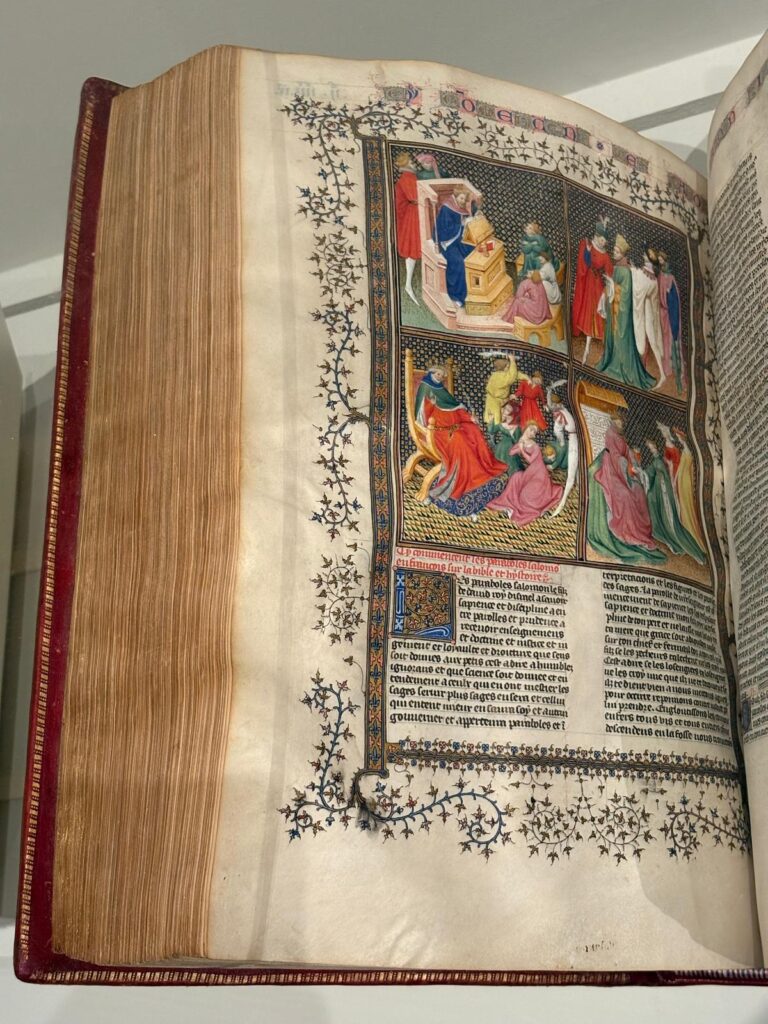

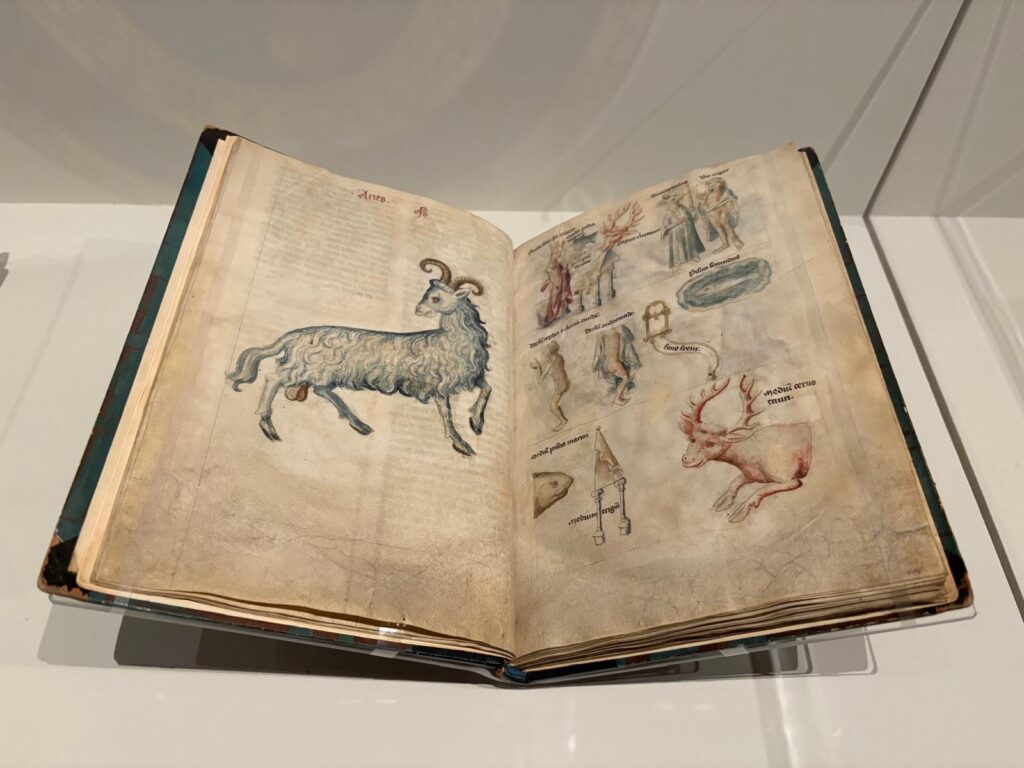

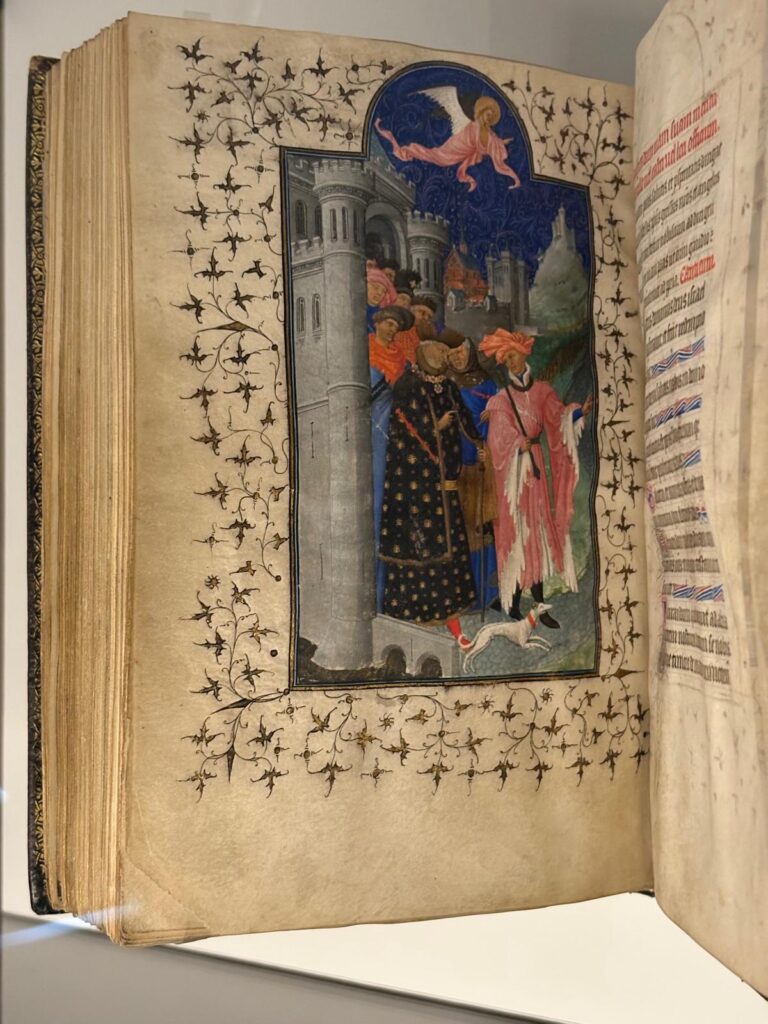

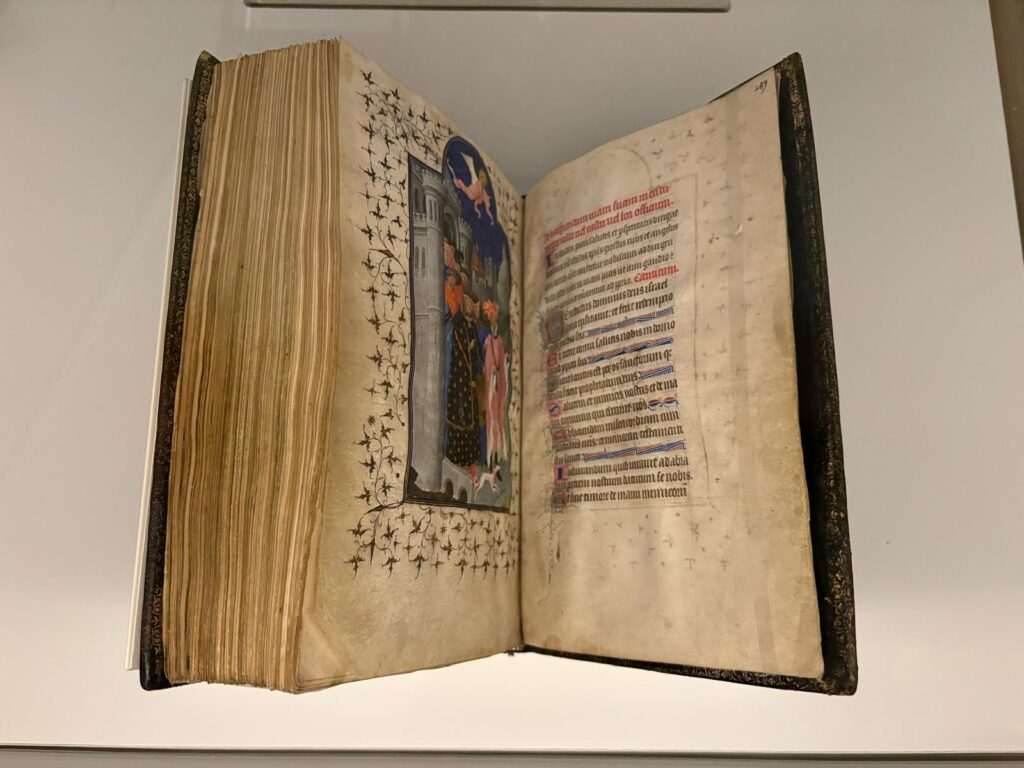

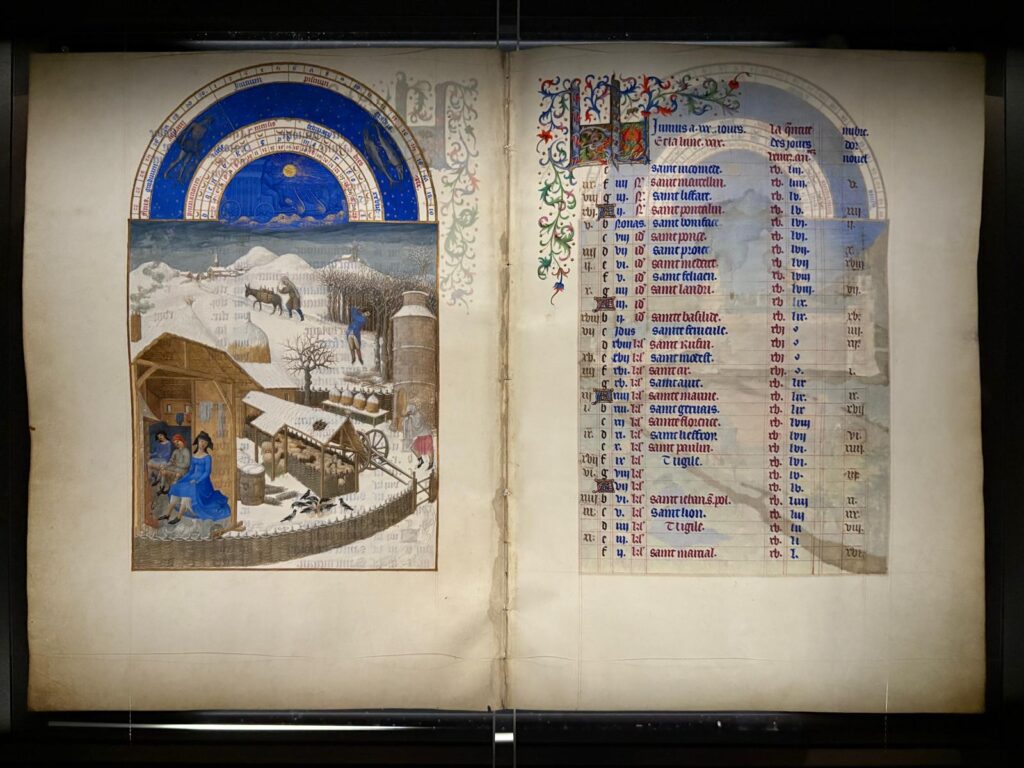

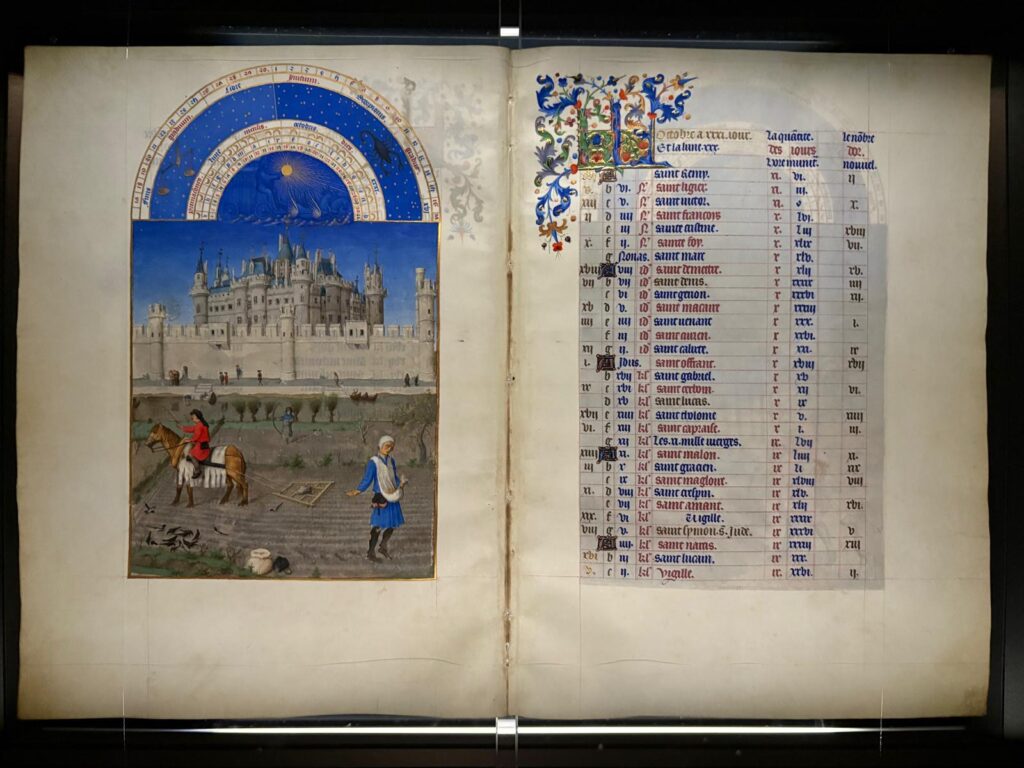

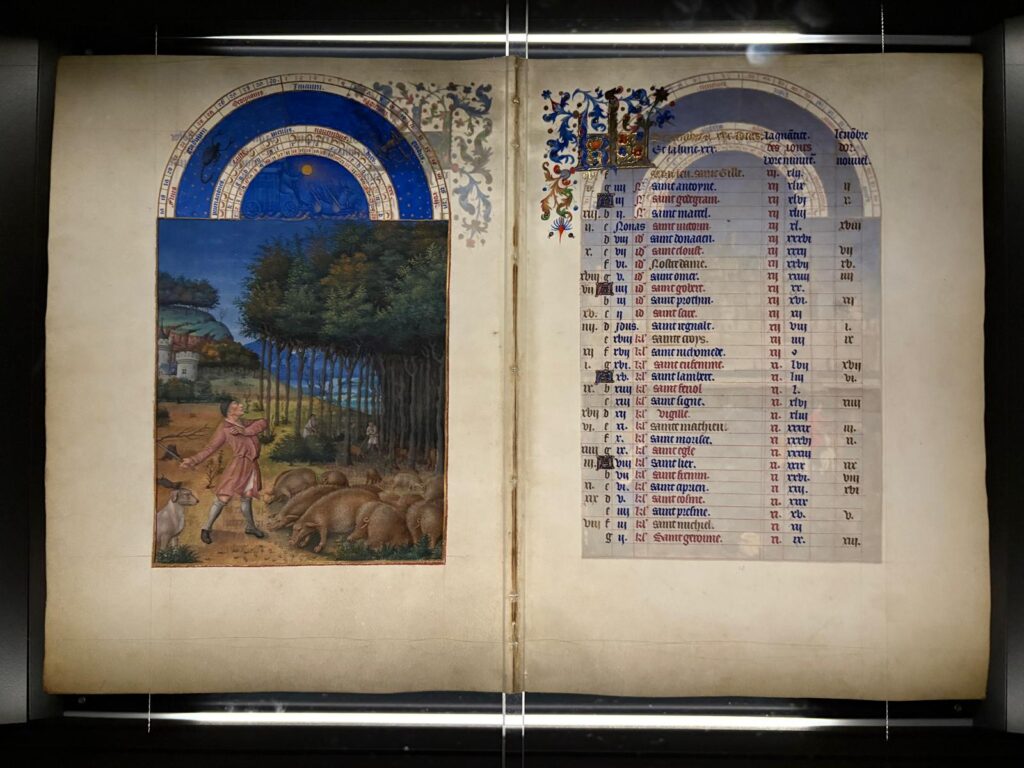

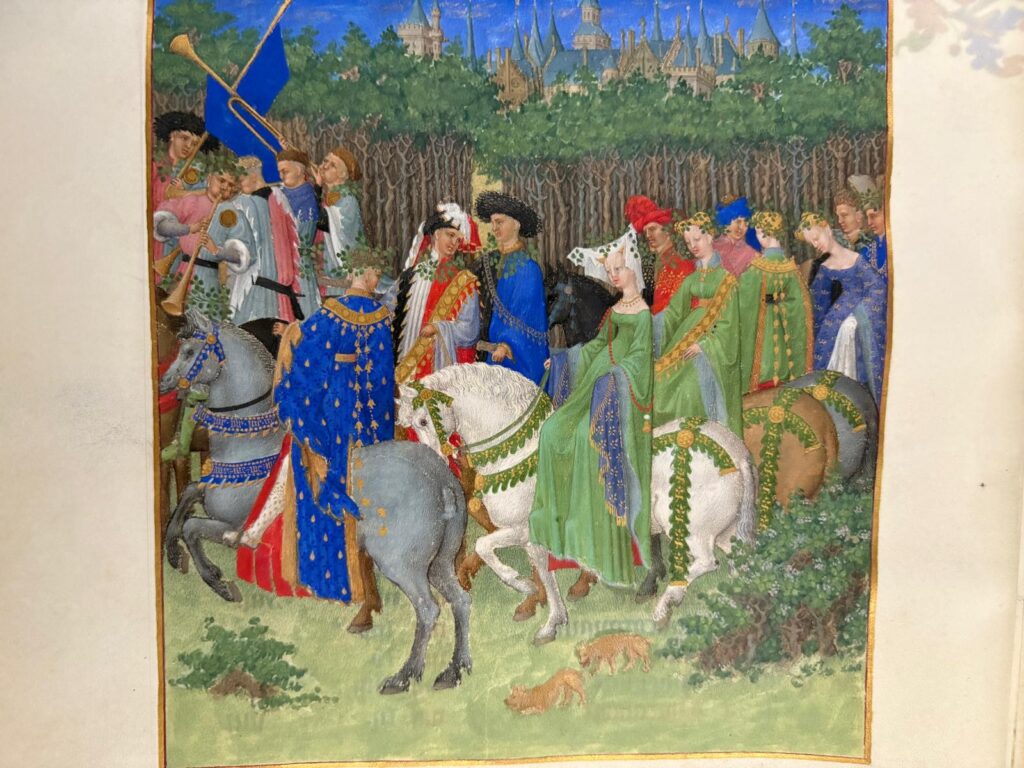

Also important is the style. The miniature paintings are in the International Gothic style, but are incredibly detailed. Some of this was down to an innovation seemingly by the Limbourg brothers: full-page illuminations. The scenes from the calendar pages are among the most famous. Each entry has details of the delights and labours of that month. Above the illustration is a zodiac chart, with a calendar of feast days on the page opposite. The month of January features a portrait of Jean de Berry. Several illustrate real castles, including the Château de Saumur and long-gone Palais de la Cité in Paris. The miniatures brim with wonderful details of people, fashions, buildings, and artistic innovations. They are truly exquisite.

A lot happened in 1416, though. Jean de Berry died, as did, seemingly, the three remaining Limbourg brothers. They may have died of the plague. The manuscript was at that point unfinished. It changed hands many times since then, and subsequent owners commissioned other artists to finish certain parts of it. Jean Colombe was one of them, and possibly Barthélemy van Eyck. Some of their contributions were finishing off pages already sketched in or started by the Limbourgs. Others were new creations, even entirely new leaves inserted into the book. And even during the Limbourgs’ time, other artists would have contributed borders and gilding. The work of many hands, but the Limbourgs as the real innovators.

How Did it End Up in Chantilly?

We now come to the story of a later duke, Henri d’Orléans, duc d’Aumale. A son of the last reigning king of France, Louis-Philippe, the duc d’Aumale lived in exile in England for many years. The last remaining vestige of his house in Twickenham is a cultural space in its own right: Orleans House Gallery.

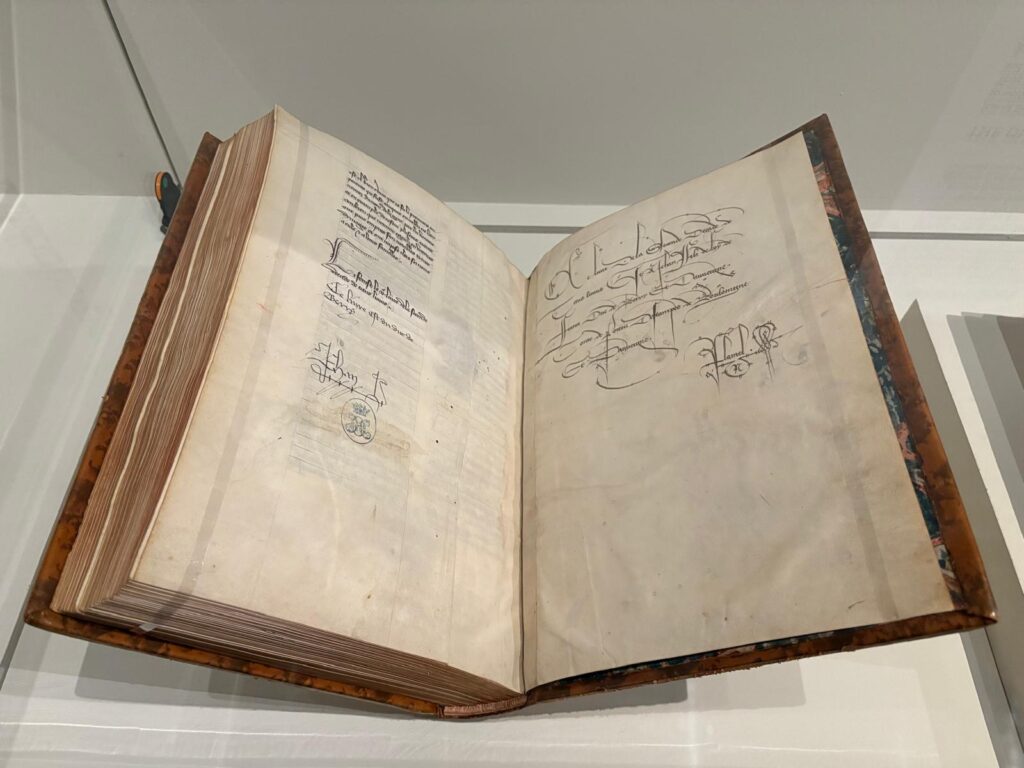

If you read my last post, or my earlier post on the Château de Chantilly, you will recall that it was the duc d’Aumale who rebuilt the Château de Chantilly. He then donated it on his death, along with his art and book collections, to l’Institut de France. He had a fine head start on that book collection, having inherited a collection of manuscripts from the Condé family, also once owners of Chantilly. Then, in 1855, a friend of the duke’s, Antonio Panizzi, mentioned a manuscript he knew was for sale. The duc d’Aumale was intrigued enough to travel to Genoa to see it. He immediately recognised it as a work produced for Jean de Berry, and purchased it for 18,000 francs.

Then begins an interesting story of how an artwork becomes a celebrity artwork. The duc d’Aumale showed the manuscript to select friends, some of whom wrote about the experience. He exhibited it in 1862 at the Fine Arts Club. He also began to engage eminent scholars to study it. And to bolster his collection to serve as a crown of which this was the jewel. It was only after the duke’s death that the manuscript was definitively linked to the posthumous inventory of Jean de Berry’s possessions, and became known under the title Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. The conditions of the latter duke’s bequest also meant the manuscript was now at Chantilly permanently, forbidden from being loaned or exhibited elsewhere.

And so, to come back to the Benjaminian quote I started with, the fame of Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry has developed almost entirely through reproductions. Starting with a major exhibition of French Gothic art in 1904, where it was represented by heliogravures. Colour reproductions further spread the manuscript’s fame from the 1940s, including in Life magazine in 1948. And, with Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry off public view since the 1980s and even access for scholars limited in recent years, it’s quite remarkable just how famous it is compared to the number of people who’ve actually seen it.

The Exhibition: Building Momentum

Right, let’s get to the exhibition, shall we? It takes place in the Jeu de Paume. This is a common building in French châteaux, a sort of indoor court for a forerunner of tennis. And actually quite a good size and sensible rectangular layout for exhibitions. But I digress again.

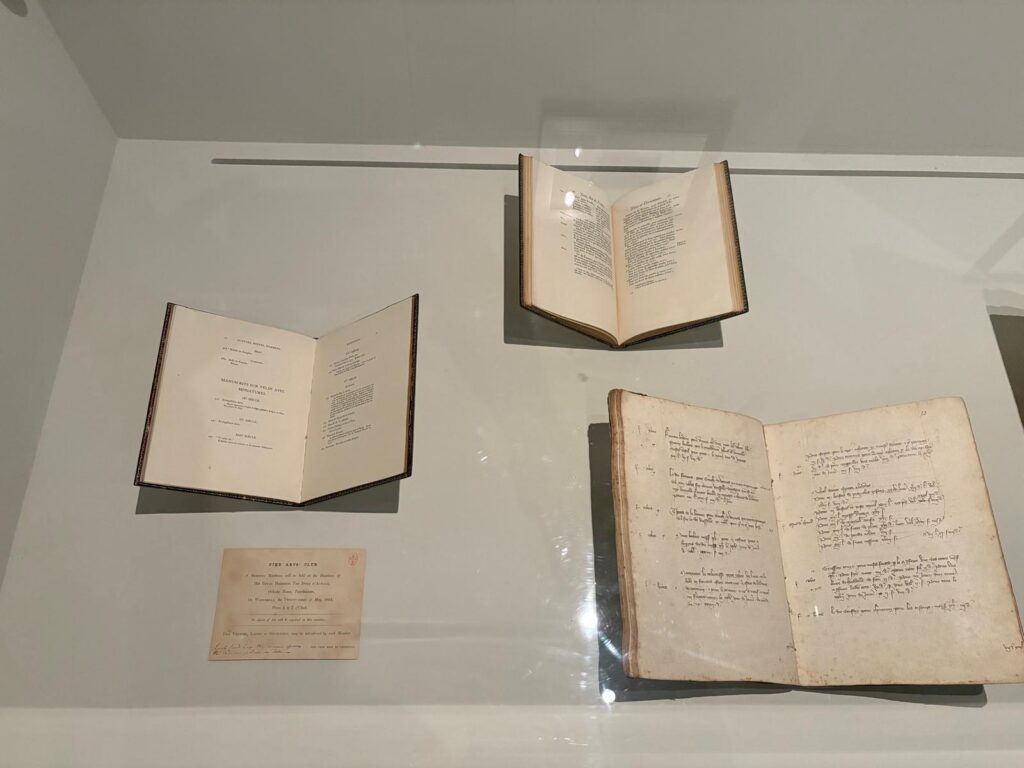

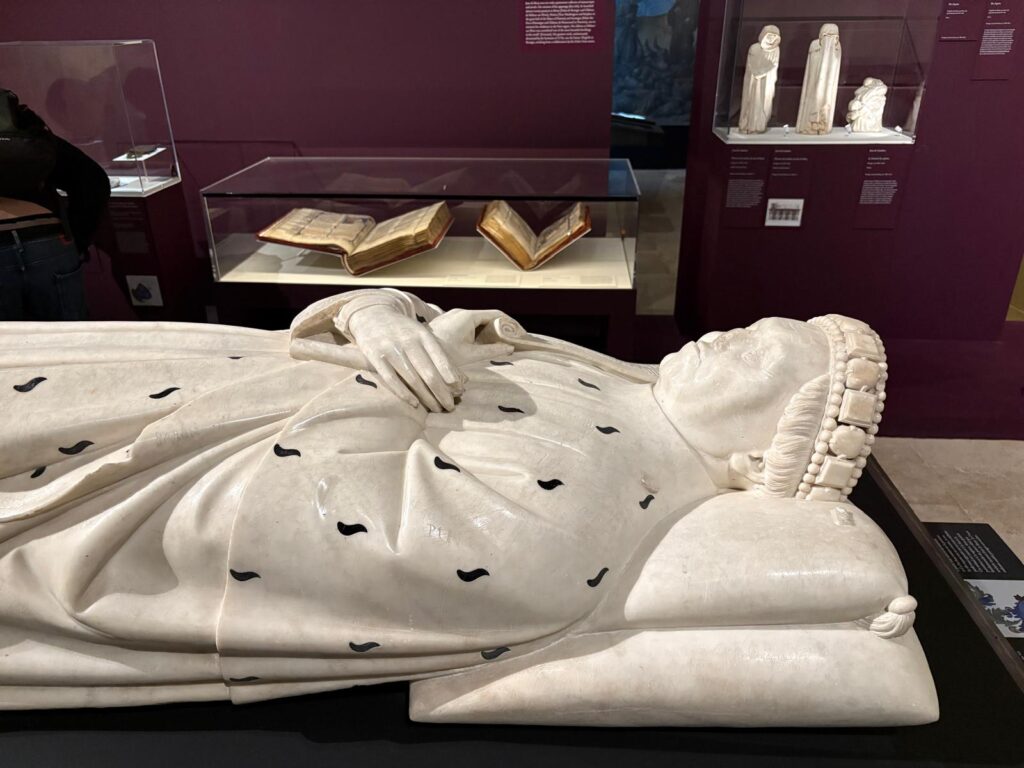

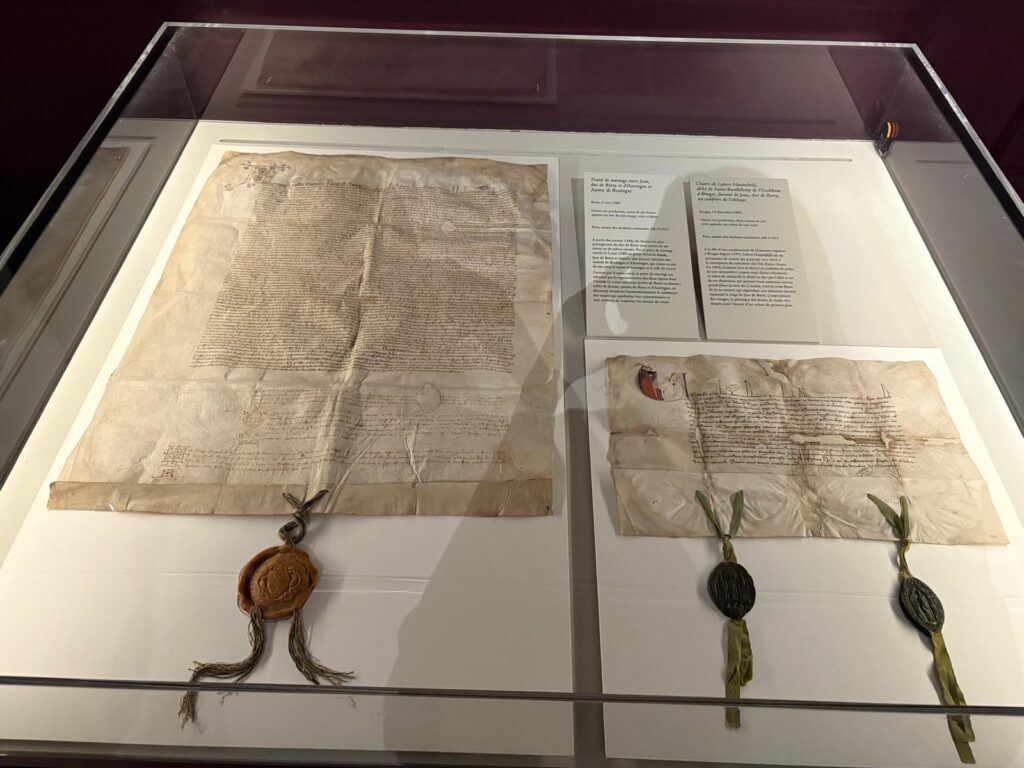

The exhibition builds momentum extremely well. The very first object, with the introductory text, is the manuscript’s custom wooden case. A reminder how precious this object is, and also that it is a devotional object rather than ‘just’ art. We then move into the exhibition proper. It starts by setting the scene. Introducing Jean de Berry and the duc d’Aumale, just as I’ve done above. There’s a good selection of archival documents, from Jean de Berry’s marriage contract, to letters pertaining to the manuscript’s 19th century acquisition. Jean himself is also there, taking up the centre of the first space, in the form of his funerary monument. He’s a big personality throughout the exhibition.

We then move into his collection. Works are divided by subject: philosophy, science, history, etc. The illuminations are striking, but we know better is coming. Nonetheless, I start a habit that probably annoyed the attendants, of getting so close to the glass cases I had to hold my breath so as not to fog them up. The other option, which several older attendees had thought of, was to bring your own magnifying glass.

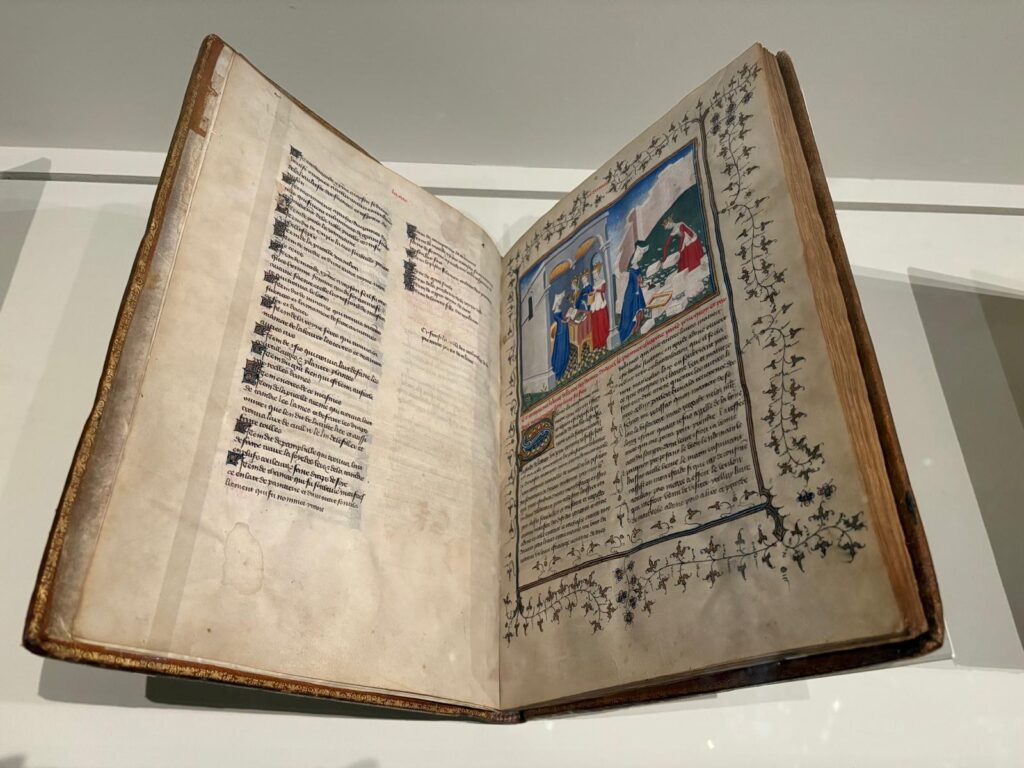

Next is a special moment. Remember how Jean de Berry commissioned six religious manuscripts himself? The curators have assembled them all. Maybe it’s because I’m a historian/museologist and an art lover, but I found it astounding to see them side by side, each increasing in scale and luxurious detail.

We’re getting close to the main event, now. But before we get there, we have a brief look at the different artists who contributed to Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. And a bit on the afterlife of the manuscript after the deaths of its patron and primary artists. There are a couple of paintings (and a remarkably well-preserved embroidery) here to relieve the otherwise manuscript-heavy exhibition. But honestly, the quality of what’s on view prevents it from ever becoming boring.

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

And now here we are, the main event. The reason Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is exceptionally on view, is that it has just undergone an extensive restoration. This was at least partly due to the presence of iron gall ink: in very common usage from the medieval period to the 19th century, but unstable and prone to corrosion. The restoration involved separating the leaves of the manuscript, meaning, very excitingly, that the calendar pages are unmounted and can all be seen. They ring the penultimate space in the exhibition, visible from both sides and with explanations of the seasonal activities depicted, the castles, etc.

I cannot emphasise enough how beautiful these illuminations are. My extensive photography may do it a little bit of justice (I was a little surprised photography is allowed, given people aren’t always good at turning off lights and flashes). But they are absolutely magnificent in real life. You know how I was bent over the glass cases, holding my breath, during the earlier parts of the exhibition? Here I had to get in line, waiting for some of the folks with magnifying glasses to look at each detail in turn, before having a go myself. And these are scenes which reward patient looking. The historian in me loved how much information about medieval life you can glean from this one book. The art lover admired the colours, the minute brushstrokes, the fashions and the observations of daily life.

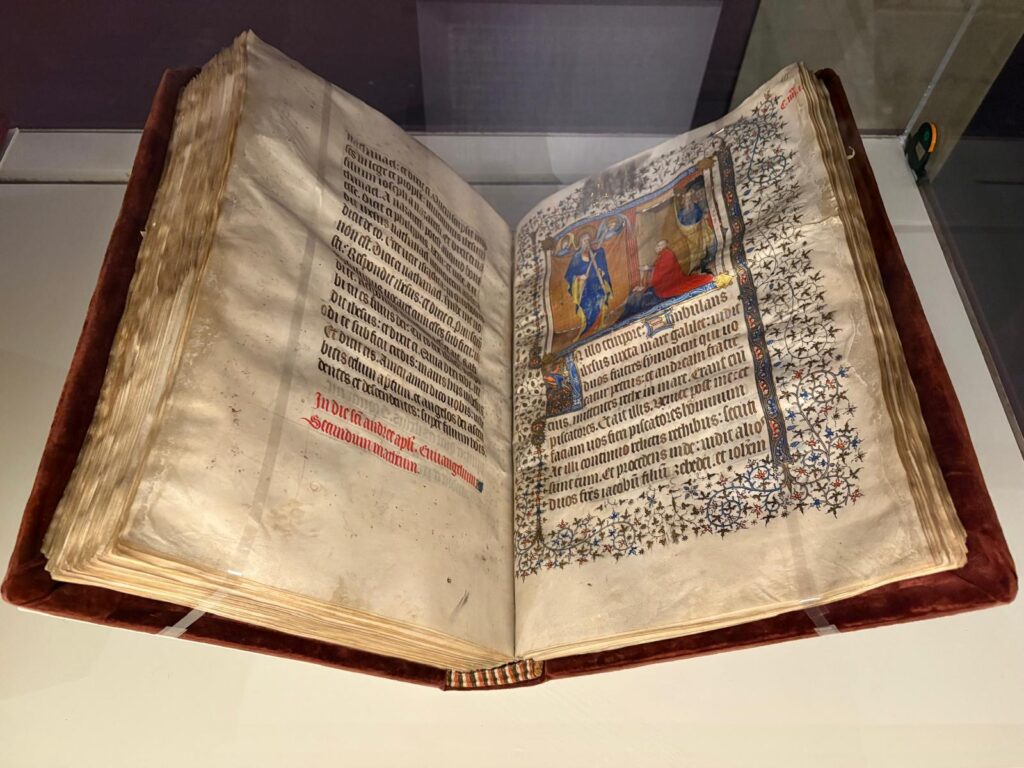

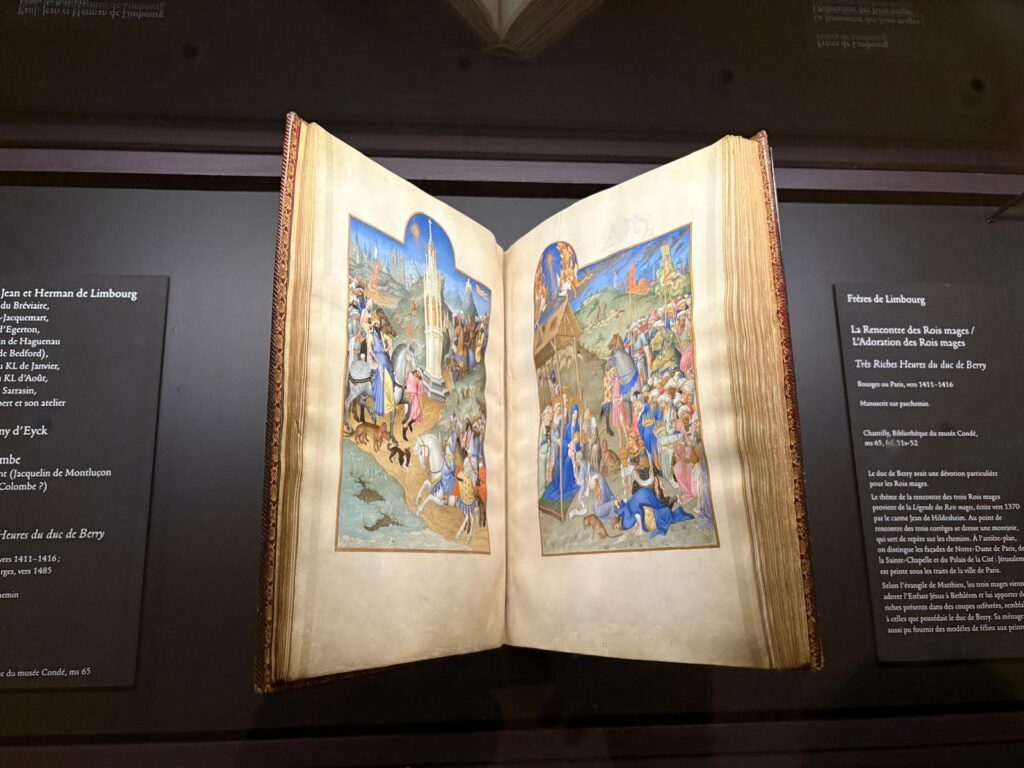

But Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry isn’t only the calendar, as famous as those images are. There’s the rest of the book besides. This is on view in the centre of the assembled calendar pages. Being a book, you can’t see all the different pages like you can with the disassembled leaves. And the page is turned every so often, so what you see will depend on your timing. We saw the meeting and adoration of the Magi. These are again illuminations by the Limbourg brothers, showing the same exceptional quality. Exotic animals draw the eye as much as the Virgin and Child.

Final Reflections: Worth the Hype?

This is a very well-paced exhibition. The space displaying the manuscript itself is relatively small, but by building up to it, you feel like you get your money’s worth. You also feel like you understand the subject well by the time you get to Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Its production, historic journey, artists, how it arrived at Chantilly: it’s all here. A nice little section at the end zooms into details in a video presentation, before you learn all the ways the manuscript has permeated our cultural life.

I would actually go one further, and say this is better than the Mona Lisa. The experience of seeing the latter is, after all, famously underwhelming. Here you have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to glimpse something that does live up to the hype. For me, with all the disclaimers about being a big-time history and art nerd, it was well worth a dedicated trip to France to see it.

A few final pointers. We visited right at the start of the day, and I recommend you do the same. The exhibition was filling up by the time we left and, as basically every object needs close-up observation, risks traffic jams at busier times. If your eyesight is not so good, you could also consider bringing a magnifying glass of your own, that wasn’t a bad idea. And my last bit of advice is to take your time. This is likely the last time we’ll see Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, after all. And definitely an exhibition that rewards slow and careful looking.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry on until 5 October 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

Very helpful review. I saw les Riches Heures, at Chantilly, August 1954. Alone in the room. Awesome.

Wow, what an experience, how fortunate! I wasn’t quite so lucky, but was very pleased to see it ‘in the flesh’ as it were.