The Grenada National Museum

The Grenada National Museum is part of a trip to St George’s for many visitors to this island nation. As a museum it confounded my expectations, but on reflection this may point to an interesting decolonising of the museum and its exhibits.

The Grenada National Museum

With a day to spend in St George’s, there was no way I was going to miss the Grenada National Museum. Firstly, have you ever known me to pass up a museum? And secondly, I like to learn about the places I visit. Thirdly, perhaps, a museum is always a nice, peaceful place to rest and recover a bit when you’ve been walking in the sun, especially up and down the hilly streets of St George’s.

And so it was I arrived at the Grenada National Museum. From the outset I could see that this was a different kind of institution than the Museum of Antigua and Barbuda, which would otherwise have been my most direct comparison. The latter played into my expectations of a national museum of a small former British colony: charming, packed with objects and information, and suffering a little from underinvestment. The former, today’s museum, didn’t. And this seems to be a recent development: my Grenada guidebook for instance, published in 2023, talks about a range of objects on view including the purported childhood bathtub of Joséphine Bonaparte (couldn’t tell you why that’s in Grenada – I did Google it).

Today, the Grenada National Museum focuses on telling stories through research, and has done away with almost all of its traditional object displays. One little area survives, and we’ll look at that in a bit. But first let’s look at the research-focused displays.

Say My Name

The first exhibition you encounter on entering the Grenada National Museum is Say My Name. A February 2025 Facebook post by the museum states:

“At the Grenada National Museum, we are dedicated to conserving not only artefacts but also the rich tapestry of stories, traditions, and knowledge that define our national identity. Each exhibit serves as a testament to our shared history and cultural legacy.”

Facebook

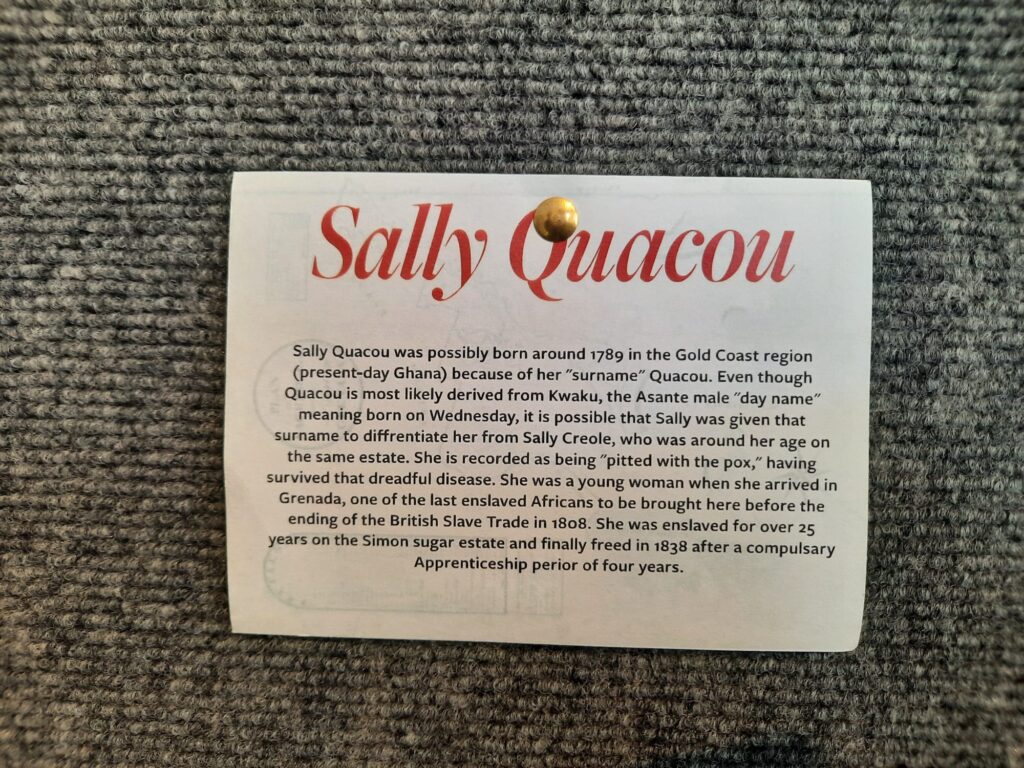

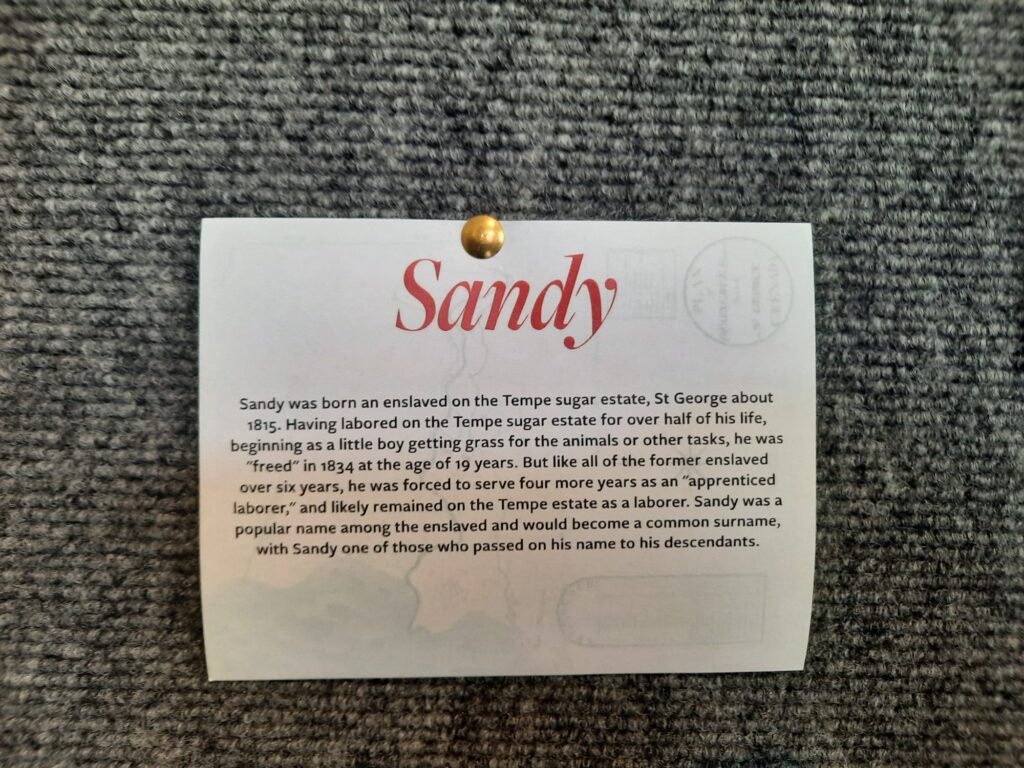

Say My Name seems to fit this bill very well. It is an exhibition reclaiming, as far as possible, the names and stories of the enslaved Africans and their descendants who worked on the estates of particular families in Grenada. Families who received reparations from the British Government upon Emancipation, while the families of the enslaved have never received any form of reparatory justice. Unless this recent development is a sign the tide may turn?

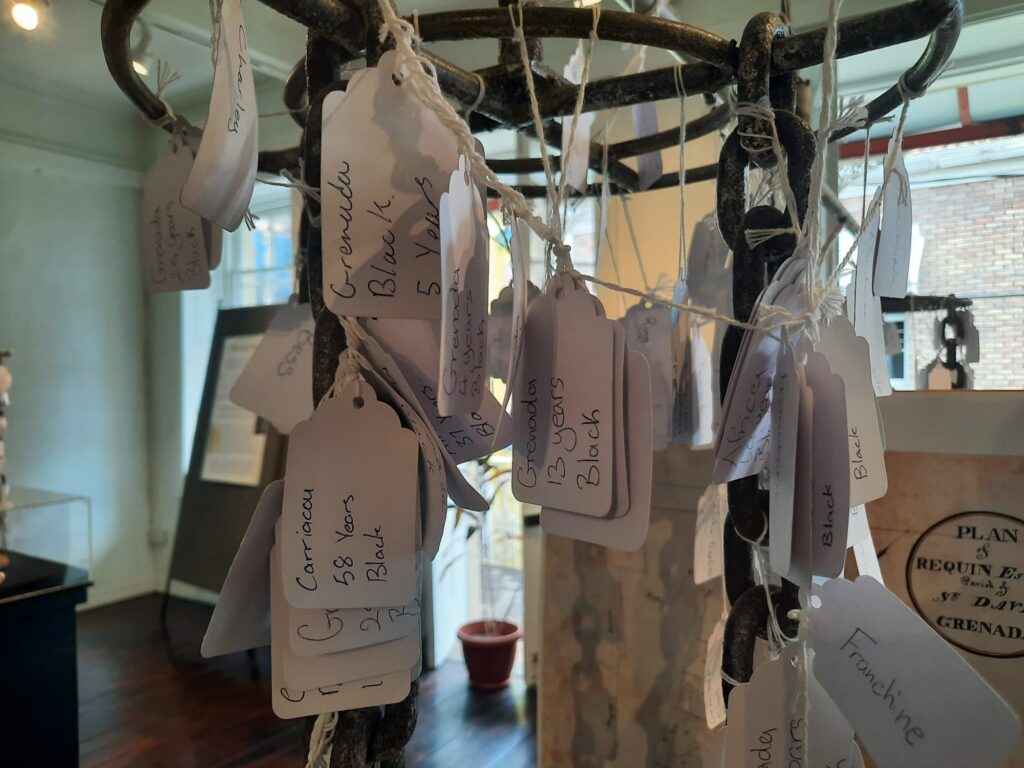

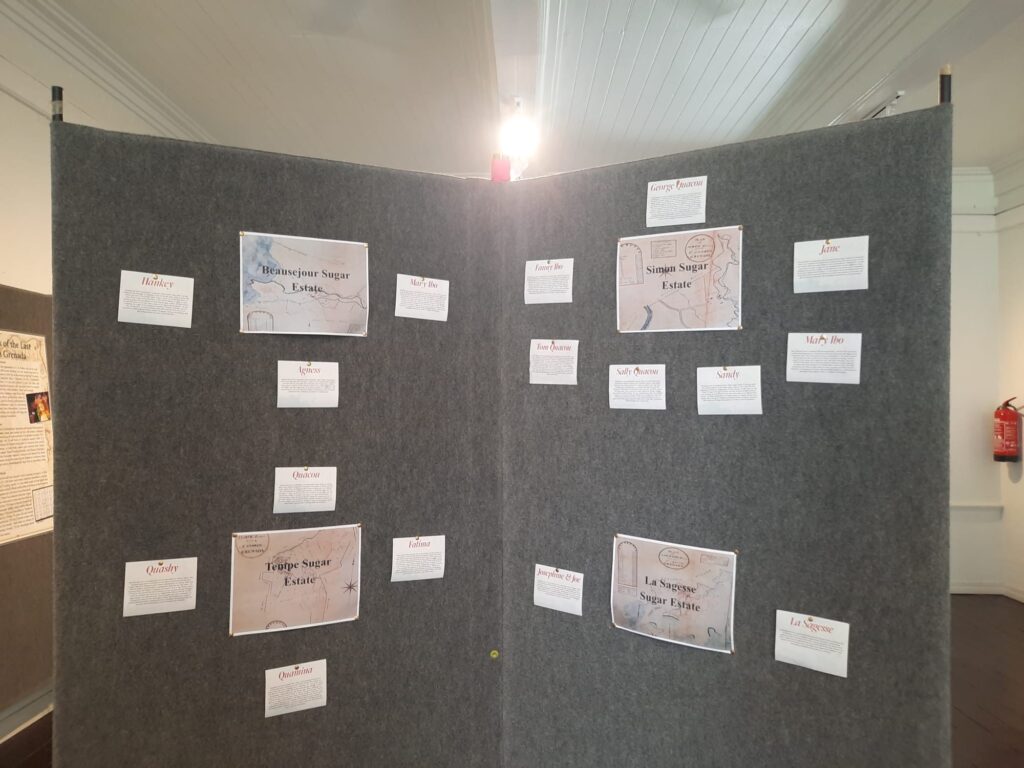

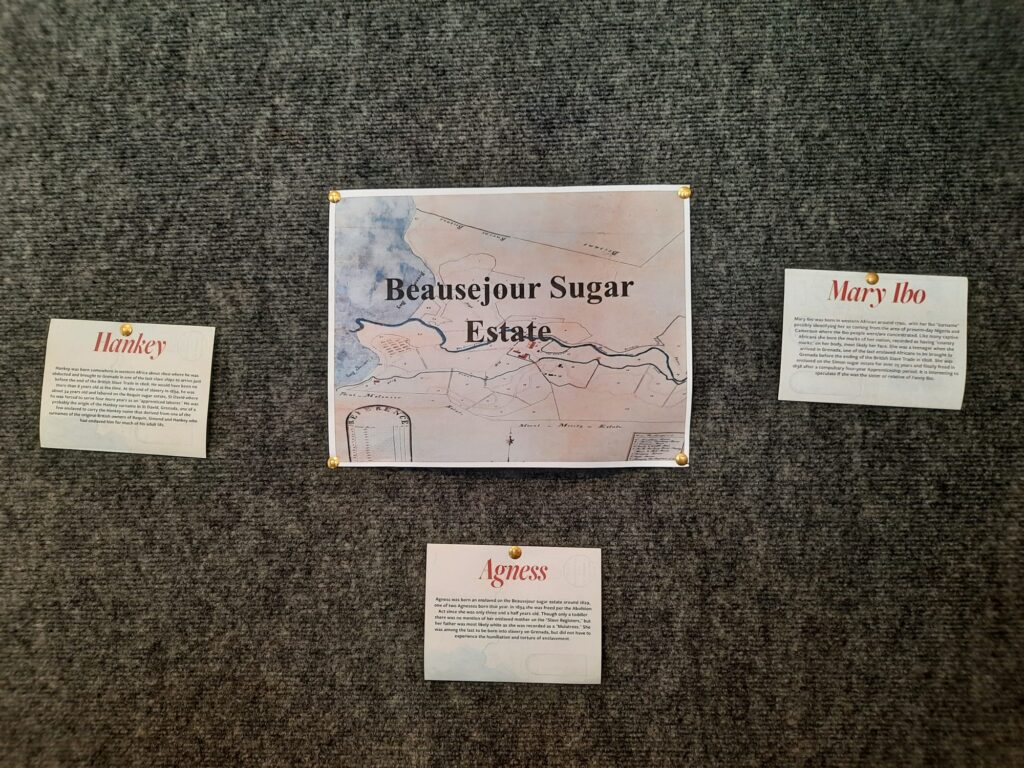

The format of the exhibition itself is very simple, and documentary. Large pin boards bear the names of several estates, with the names of people who worked there pinned around them. The names recorded by plantation owners were, of course, often names given to enslaved individuals to distance them from their previous homes and identities. That is teased out, while there is also an acknowledgement that these given names also formed part of new identities. The scale of Grenada’s population of enslaved people is represented by many little white tags: names inscribed where known, or blank where not.

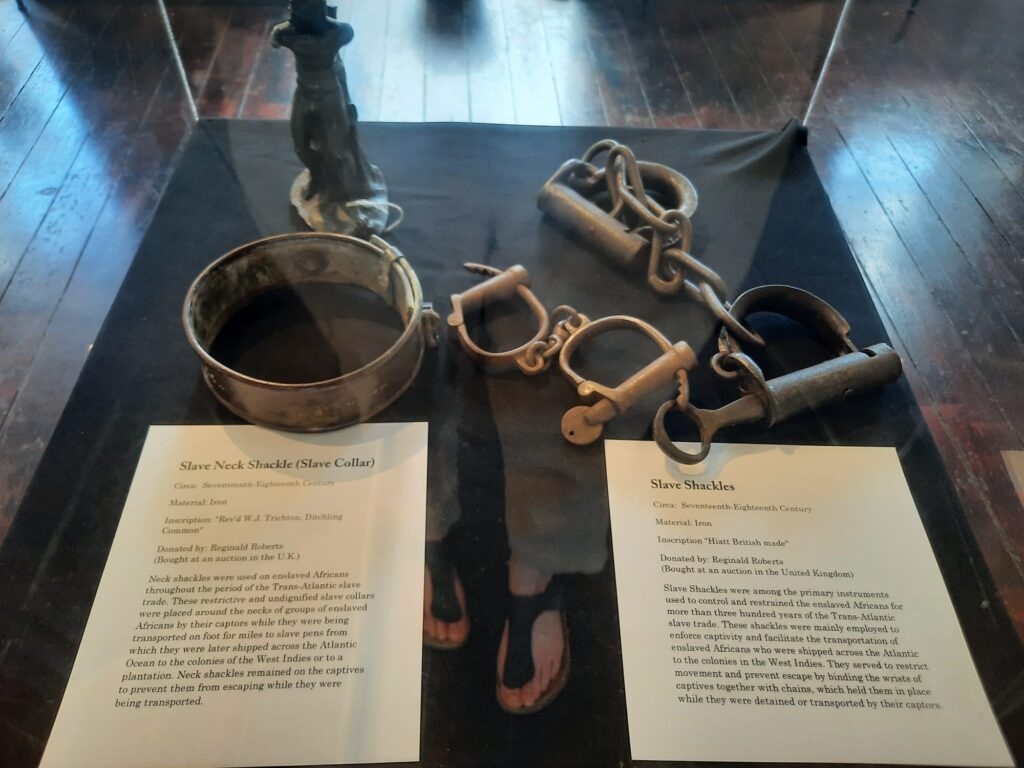

Additional texts explain ancillary events and issues, including Emancipation in 1834, and the subsequent betrayal of long ‘apprenticeships’ for the formerly enslaved. As an opening statement from the Grenada National Museum, it’s powerful. Here is a museum which is not tied to how things have always been, but is willing to give space over to new ways of understanding and honouring the past. The few objects which form part of the exhibition, while powerful, are almost unnecessary given the strong archival research-based approach. A tour by a museum staff member helped to orient us within the exhibition and ensure we had the basics of Grenadian history in order to grasp it.

Signs of a Permanent Collection

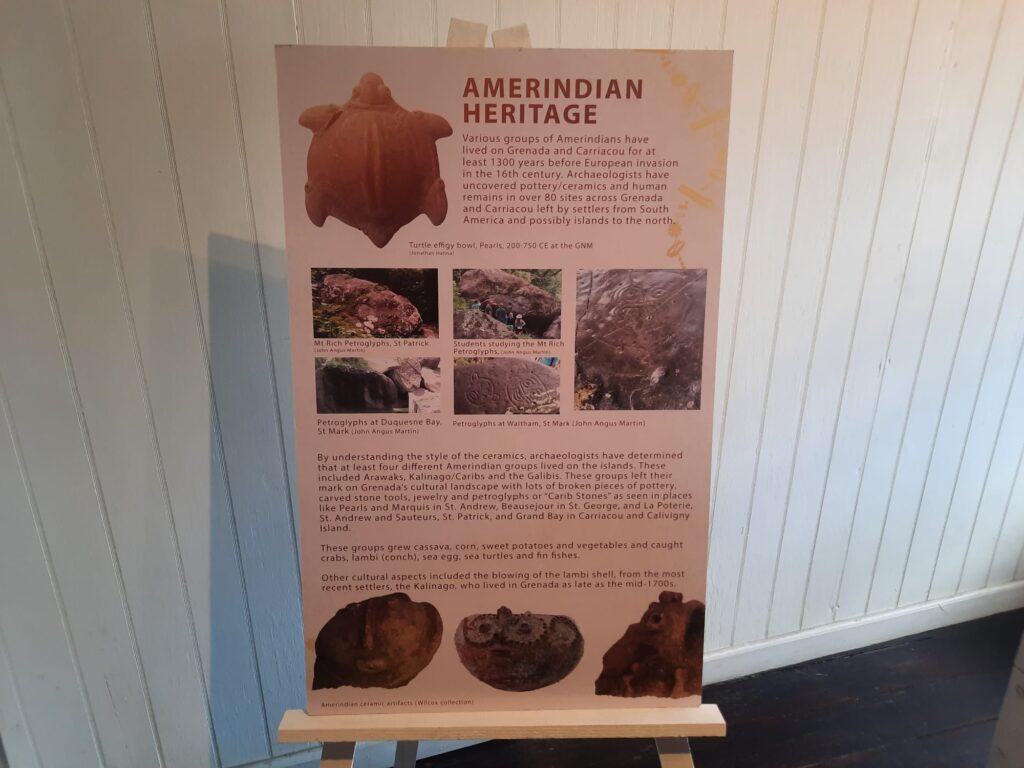

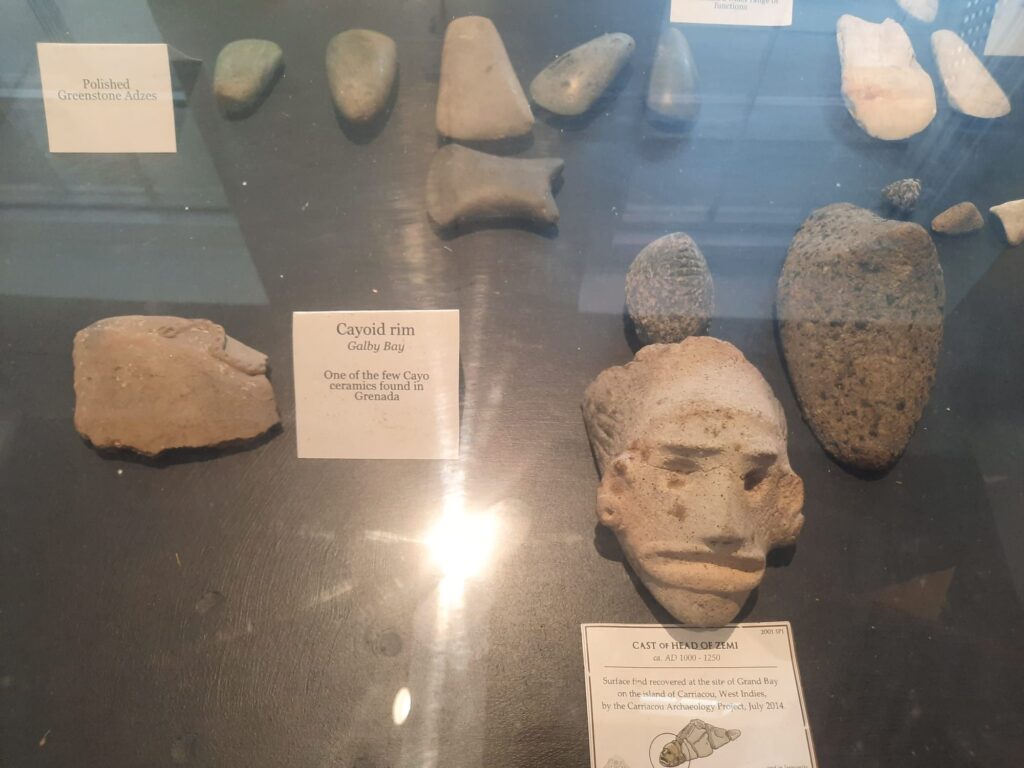

Onwards, then, to the next room. There were hints here that the museum may once have been more like my preconceived (and probably colonially-rooted) notions. A glass cabinet of artefacts greeted me in one corner. Inside were various pre-Columbian (or Amerindian in the local parlance) objects. Interesting to an archaeology lover such as myself, but admittedly a little monochromatic and with minimal labelling. Next to the cabinet a canoe stretched out its dark form. On the wall facing were replica tools, of the type I imagine form part of demonstrations to school groups.

On the one hand, my traditionalist museological brain was pleased to see the museum “anchored” by its permanent collection. However, on the other hand, it was much less immediate and engaging than Say My Name. I paused briefly to look at the artefacts, while the Urban Geographer headed straight to the next modern display.

Decolonising a museum can come in many forms. A museum as we know it is, after all, a Western construct. Socio-museology in the 1970s rethought what a museum could be, with particular focus on groups marginalised by traditional, elitist institutions. The Grenada National Museum – if decolonising is what they are after – have moved towards it by working within the museum framework, but sweeping away legacy approaches to display and collections. Fewer cases gathering dust, more new research that means something to today’s Grenada. The same epochs of history, but told from new perspectives. With no indigenous peoples remaining in Grenada today, perhaps the impetus to sweep away the old here was less urgent.

National Museum, National History

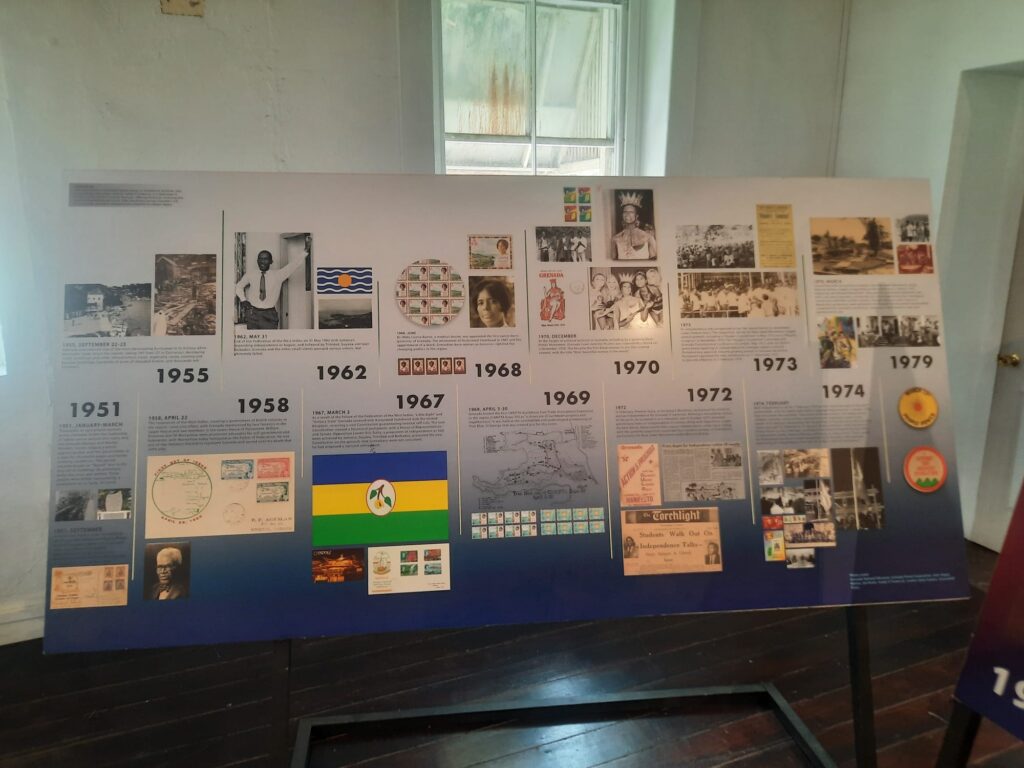

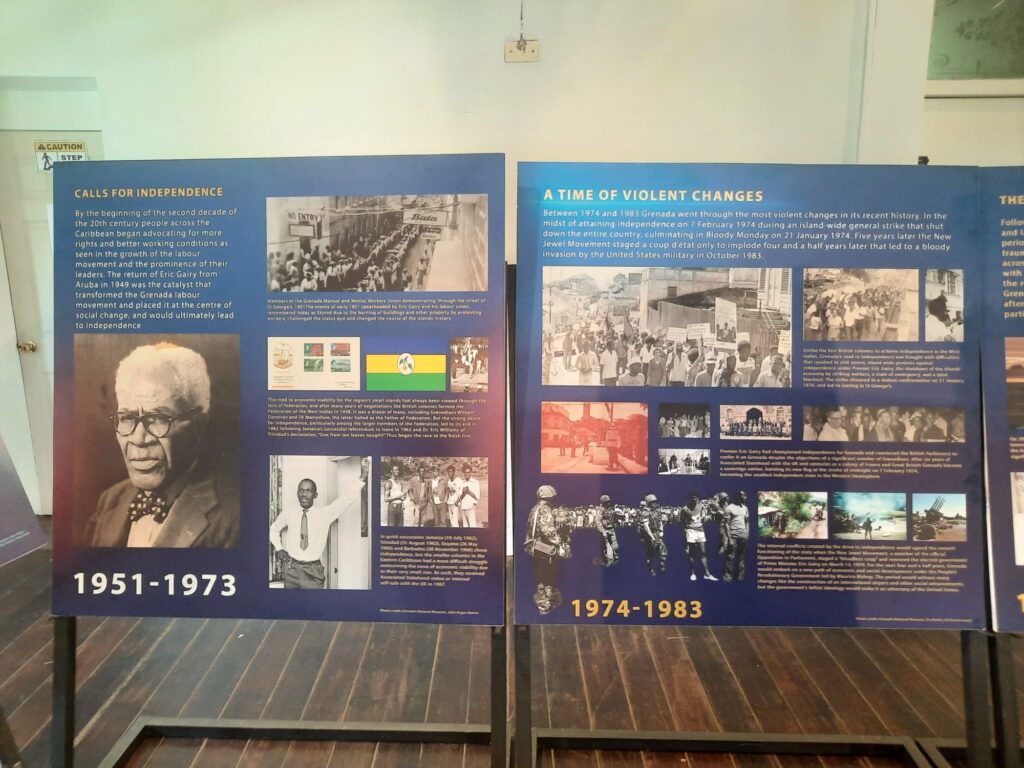

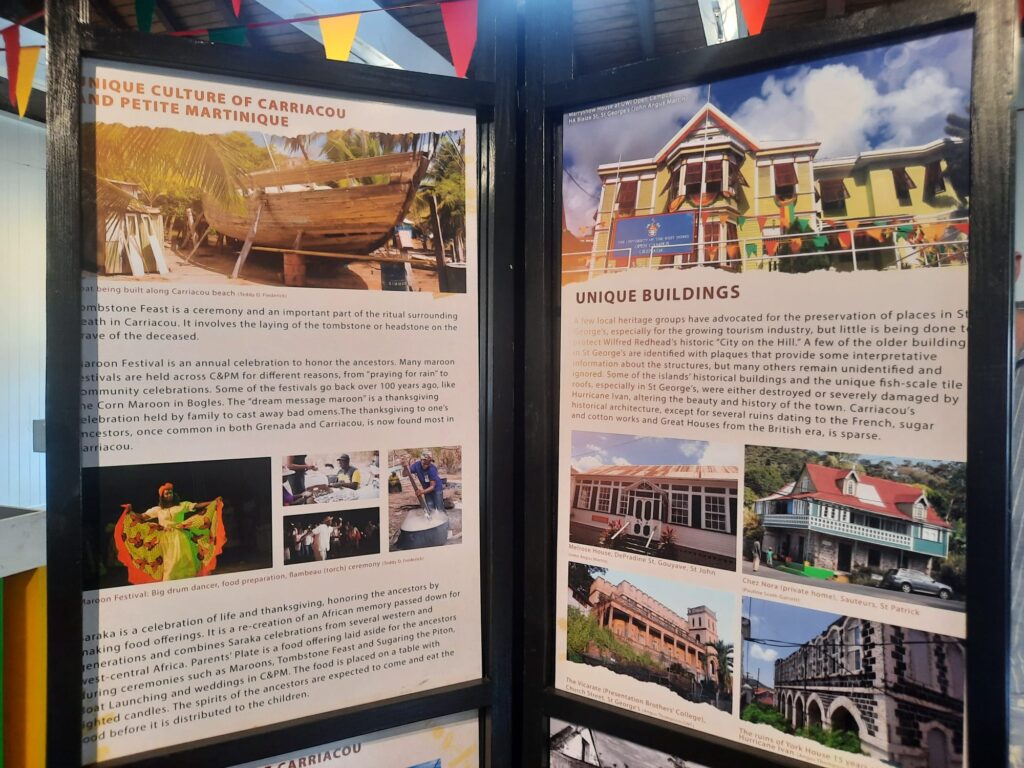

And so I’m going to summarise the rest of the museum experience in a few short paragraphs. I alluded to the next modern display, which the Urban Geographer made a beeline for. This was a historic timeline, celebrating 50 years of independence (in 2024). The main timeline is on panels around the outside wall. Supplementary topics (like Carriacou and Petite Martinique, or historic buildings) are on displays in the centre. The thing about removing objects from the museum and replacing them with text is that after a while it’s a lot of reading. I skipped over some bits, focused on those that interested me, and then went to sit down while the Urban Geographer finished.

Just one more room remaining. And I was surprised that it was a temporary exhibition space. When we visited, it had a display of a private collection of photographs of beauty queens. Why was I surprised? Well, firstly the building seems bigger than what is on display inside. Even now, I wonder if I missed something. But I don’t think I did. And there’s so much more to say about Grenada. Different cultures, contemporary society, reframing collections from the colonial era. Many possibilities. But perhaps this is where the Grenada National Museum serves the interests of local people by putting on changing displays.

It’s good to be challenged. And as much as I like an old-fashioned museum (I even wrote a whole post about it once), it’s good for me to reflect on the unconscious biases that feed my expectations of what a museum will be. The Grenada National Museum wasn’t what I thought it would be. But I liked it, and learned a lot. With the Carriacou Museum closed due to hurricane damage, this information-led approach is probably also more climate-safe and flexible. Whatever the drivers, I’m glad I could deepen my knowledge of Grenadian history and people during my visit.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.