Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985-2025 – ICA, London

Lubaina Himid and fellow Black and Asian women artists continue a project decades in the making in Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985-2025.

A Return Trip to the ICA

With London’s cultural scene as vast and vibrant as it is, there are most definitely a few venues I don’t visit often enough. Not through lack of willing. But the months come and go, exhibitions open and close, and there isn’t enough time to see them all. Sometimes this results in last minute dashes to see something before it closes, sometimes it means missing them entirely. And which venues I patronise or miss can come down to something as simple as which mailing lists I’m on or who I follow on Instagram.

One of the venues I know I don’t visit often enough is the ICA, or Institute of Contemporary Arts. I haven’t been since 2021, and that visit was my very first. I loved it, and yet somehow it’s been four years and I haven’t been back! How time flies. It’s especially shameful when you learn that it’s only a short walk from my offices, and is one of the few London venues with late opening times so is perfect for an after-work cultural outing.

But no matter, the point is that I did make it back. And will hopefully make it back with more frequency from here on out. As well as art exhibitions there’s a great programme of events at the ICA including a lot of film screenings. Check out the programme here. And what was the exhibition that tempted me back to the ICA? Well it’s an interesting one, giving insight into the ICA’s own history as well as the careers of several Black and Asian British women artists. Some names I was familiar with, others were new to me. Let’s get stuck in now and find out what it’s all about.

The Thin Black Line

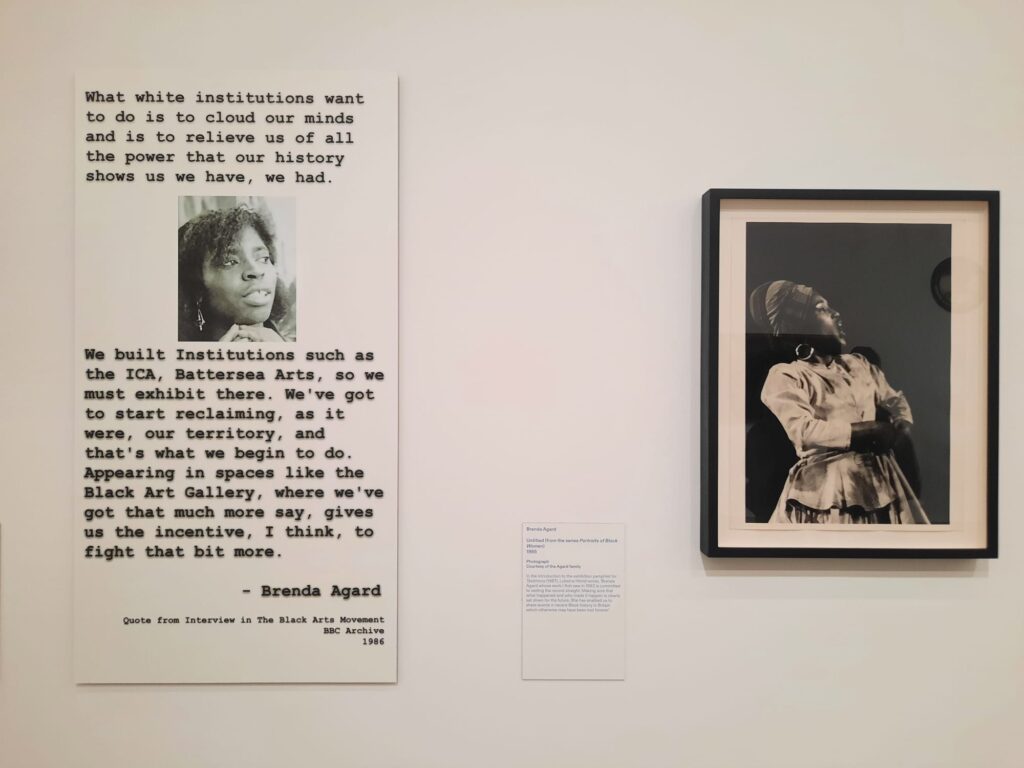

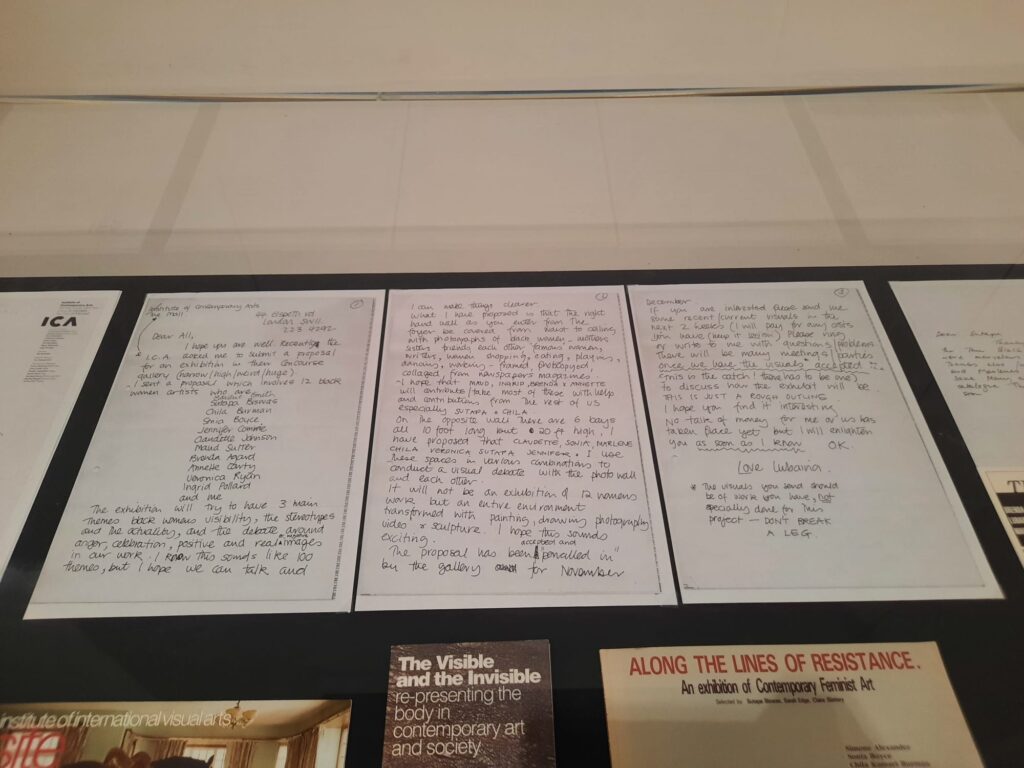

Forty years ago, following the First National Black Art Convention at Wolverhampton Polytechnic in 1982 and two other group exhibitions at the Africa Centre and Battersea Arts Centre, a group of young women organised an exhibition of their work to be shown at the ICA. The Thin Black Line came with a whole programme including film, performance and music, curated by Lubaina Himid. Himid also curated the other two exhibitions mentioned above, and seems to have been a powerful driving force promoting visibility and recognition for Black and Asian women artists. Letters included in this exhibition show her rallying the troops with a singular vision. The list of artists she proposed to the ICA was almost exactly the final list.

An important point to note about The Thin Black Line is its grounding in the concept of political blackness. This is a concept I’ve referenced once before but it’s also central to, for instance, the founding of the Association of Black Photographers, now Autograph. Political blackness used Black as an umbrella term for all groups likely to face discrimination based on their skin colour, hence the inclusion of Asian artists here and in similar projects. The term gained favour in the 1970s in the UK but fell out of fashion from the 1990s.

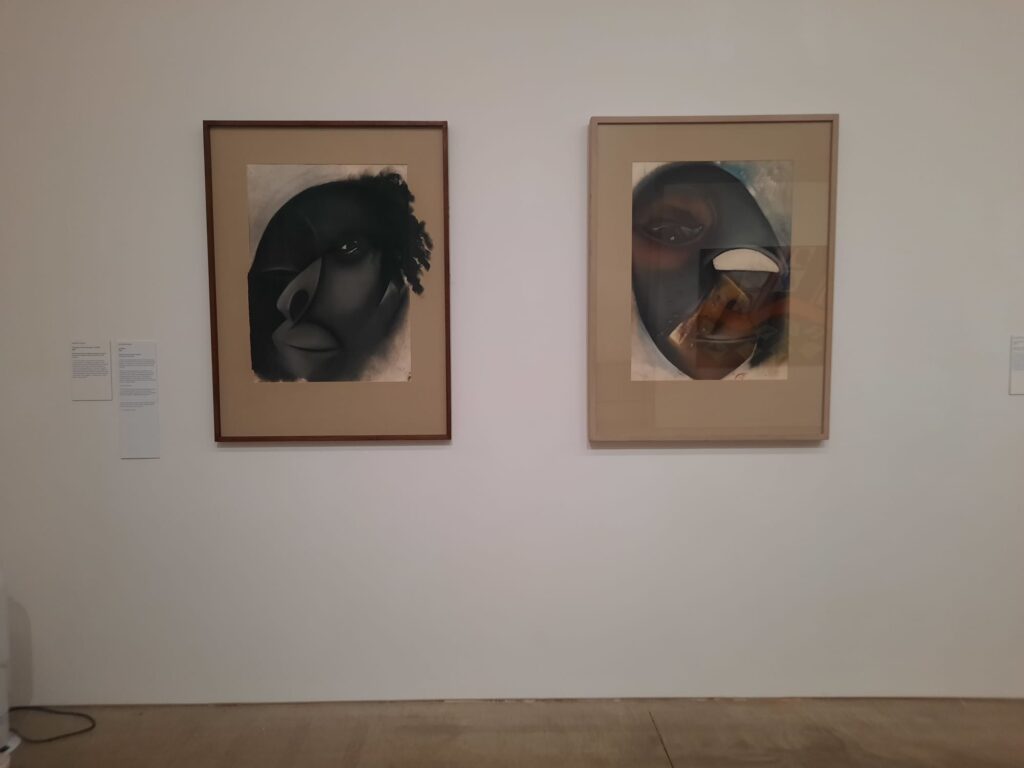

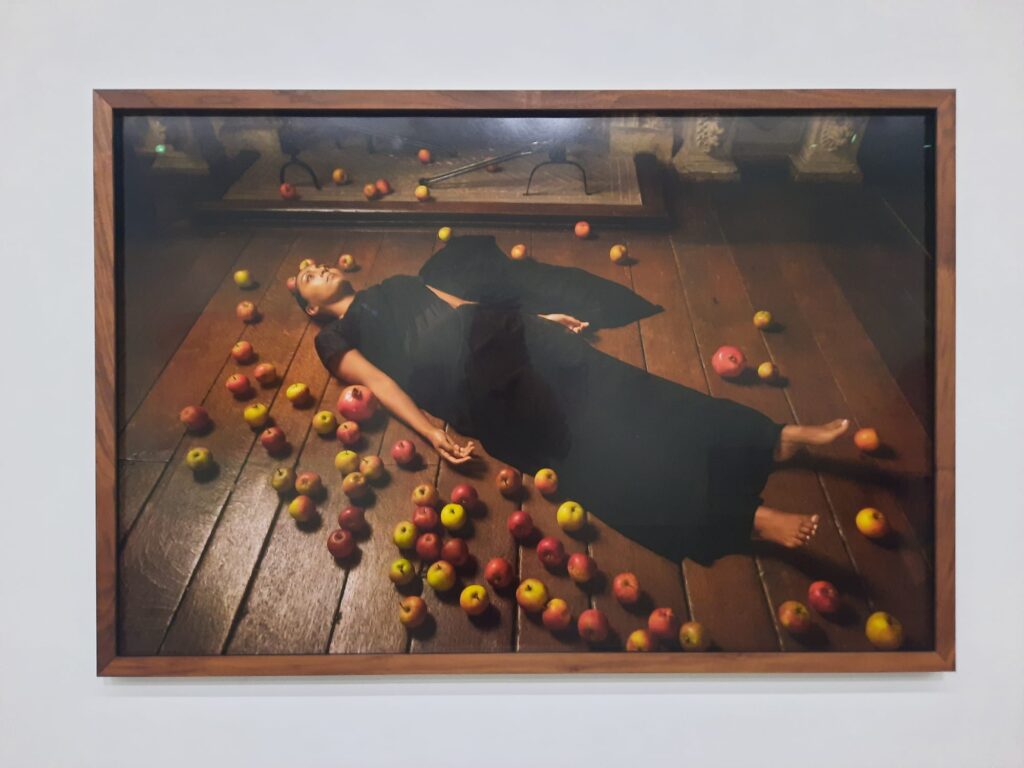

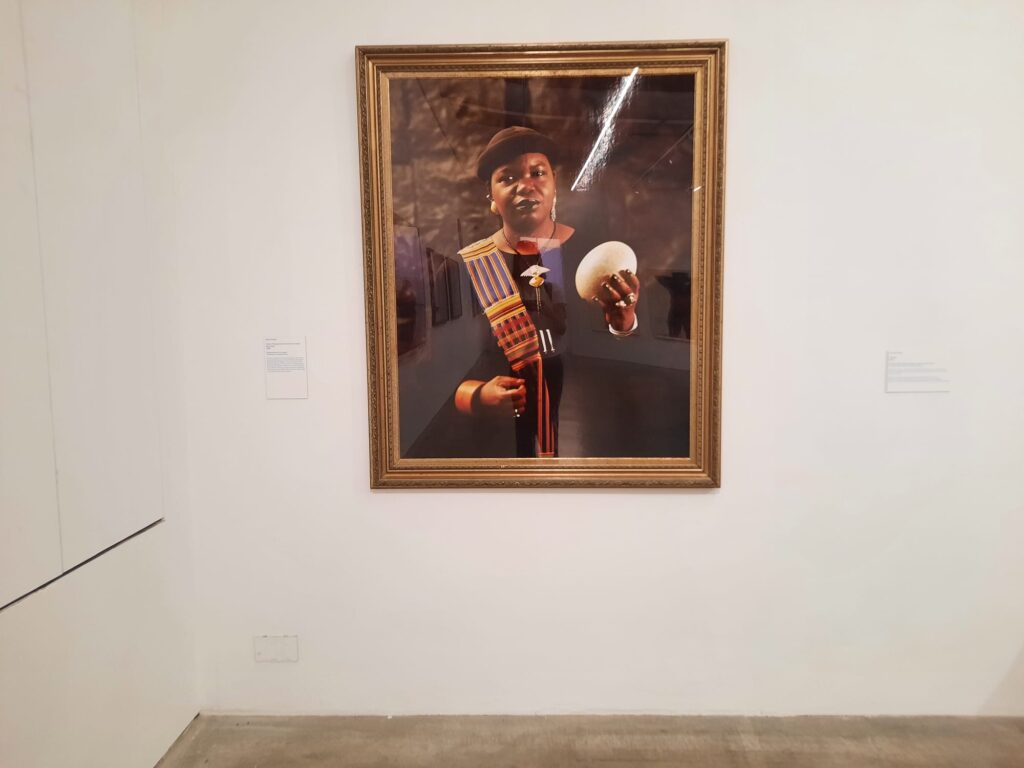

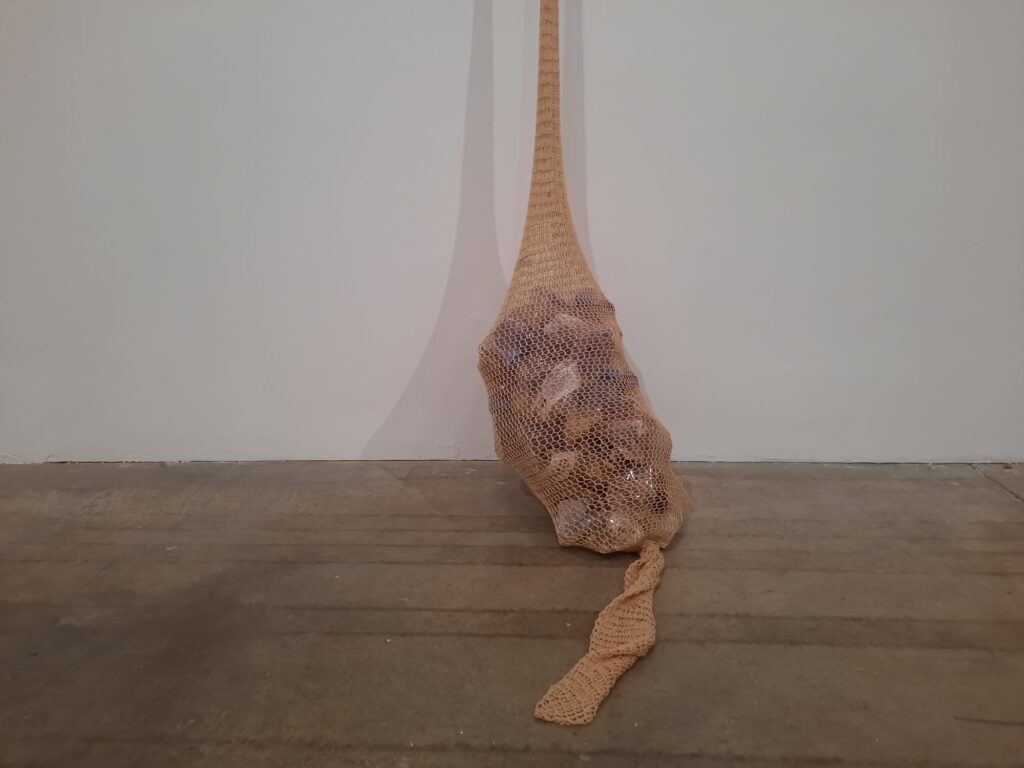

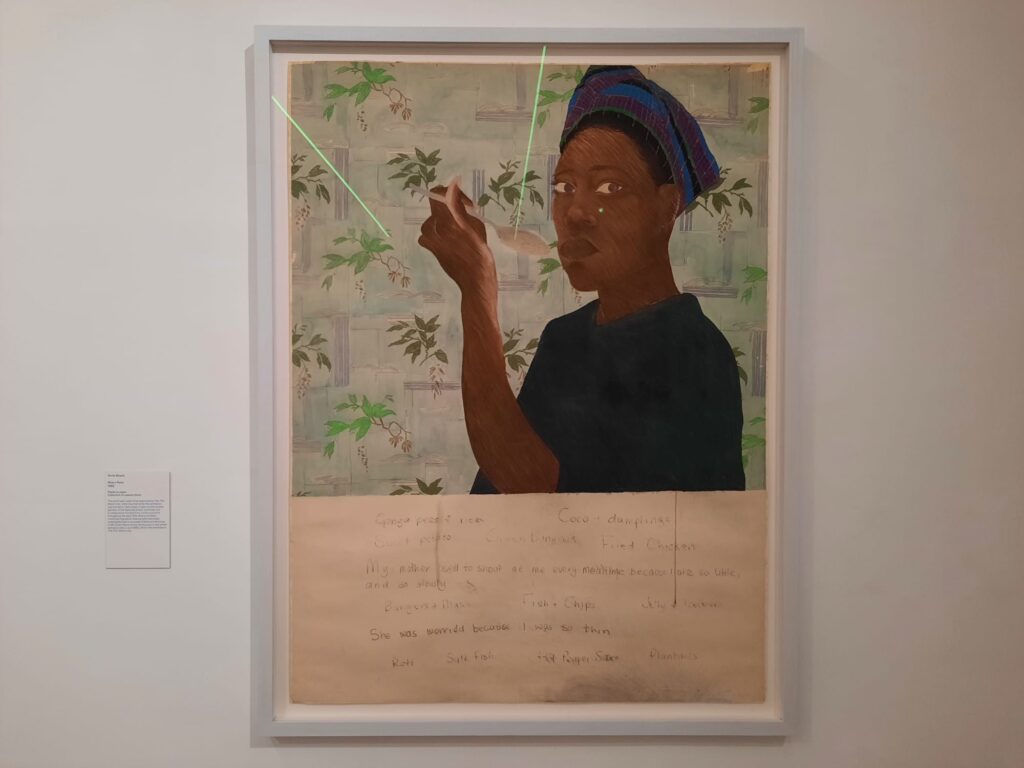

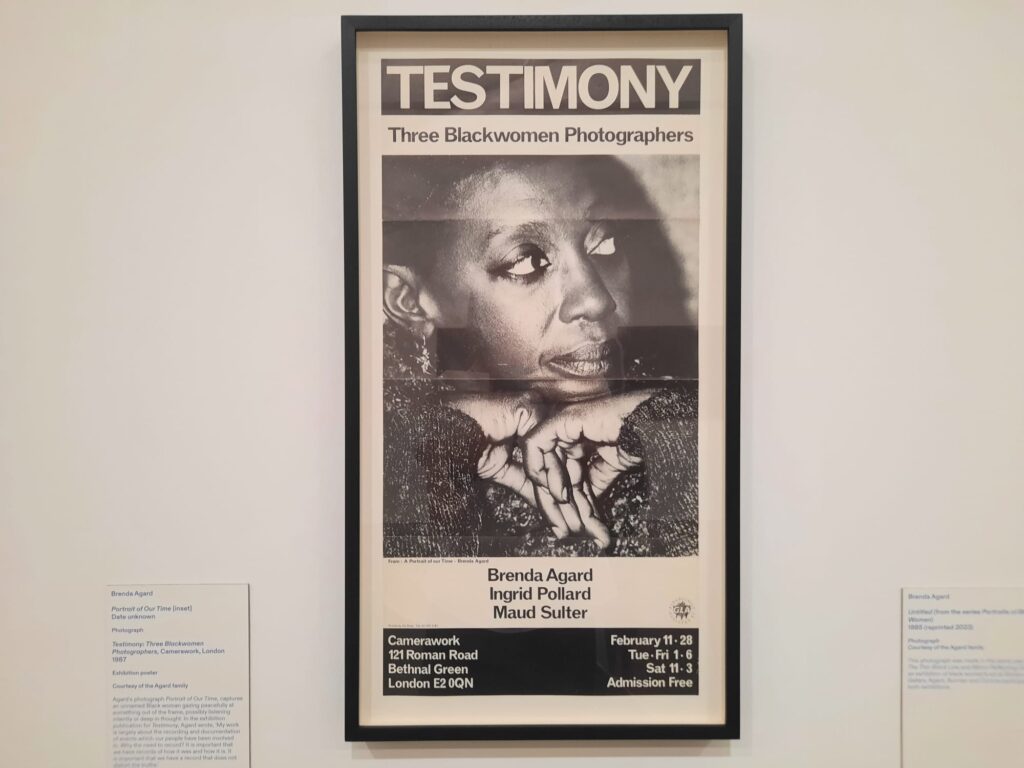

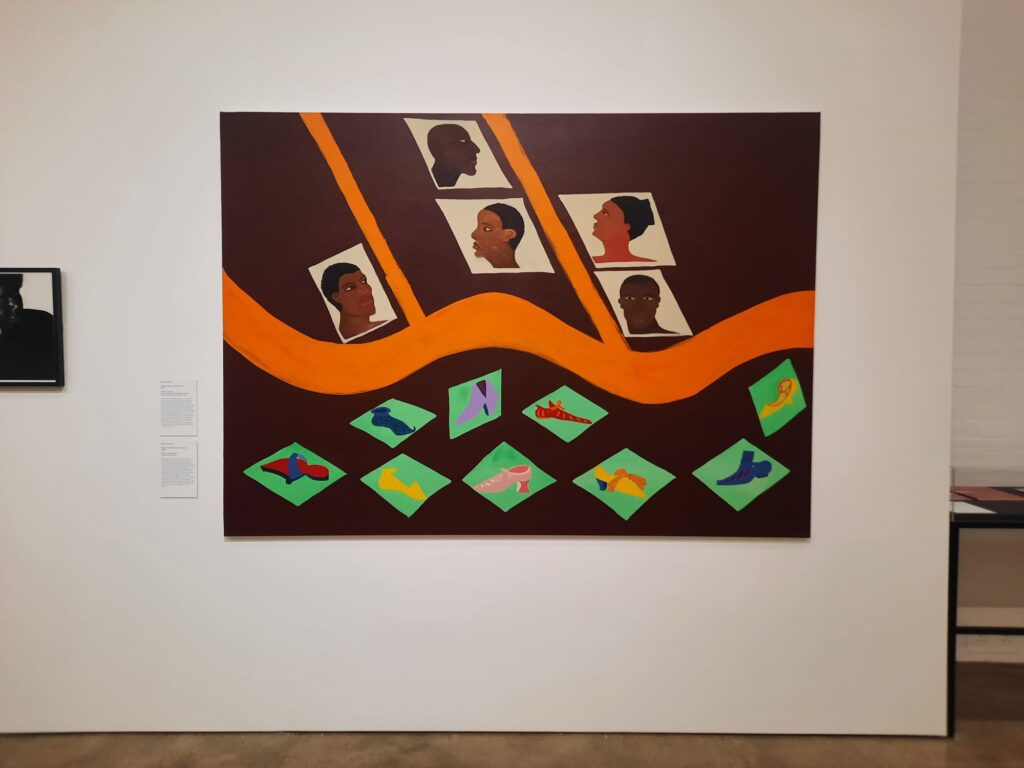

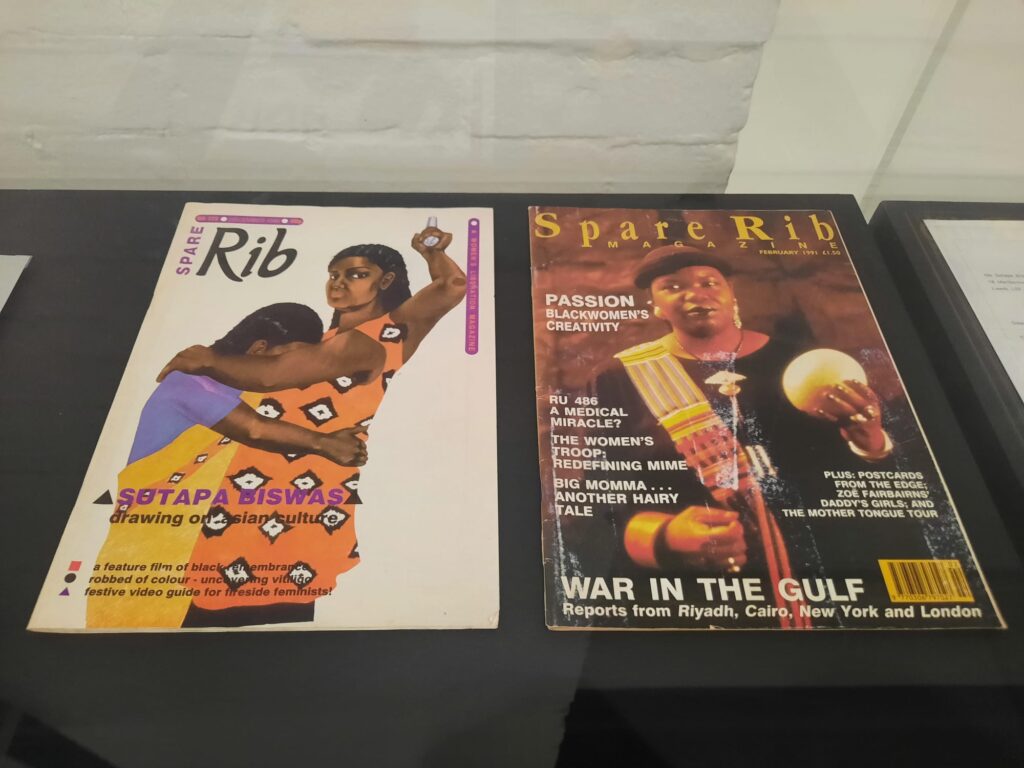

So The Thin Black Line brought together works from eleven Black and Asian British women artists. I’d seen work by Sonia Boyce, Ingrid Pollard and Chila Kumari Burman before, as well as Himid. Other artists like Brenda Agard, Jennifer Comrie, and Maud Sulter were, to me, new discoveries. Between them they cover a range of media, from painting to photography to sculpture and film. The original exhibition aimed to make these women and their work visible against societal and art industry barriers, which Himid describes in the current exhibition materials as a “brutal experience”.

Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985-2025

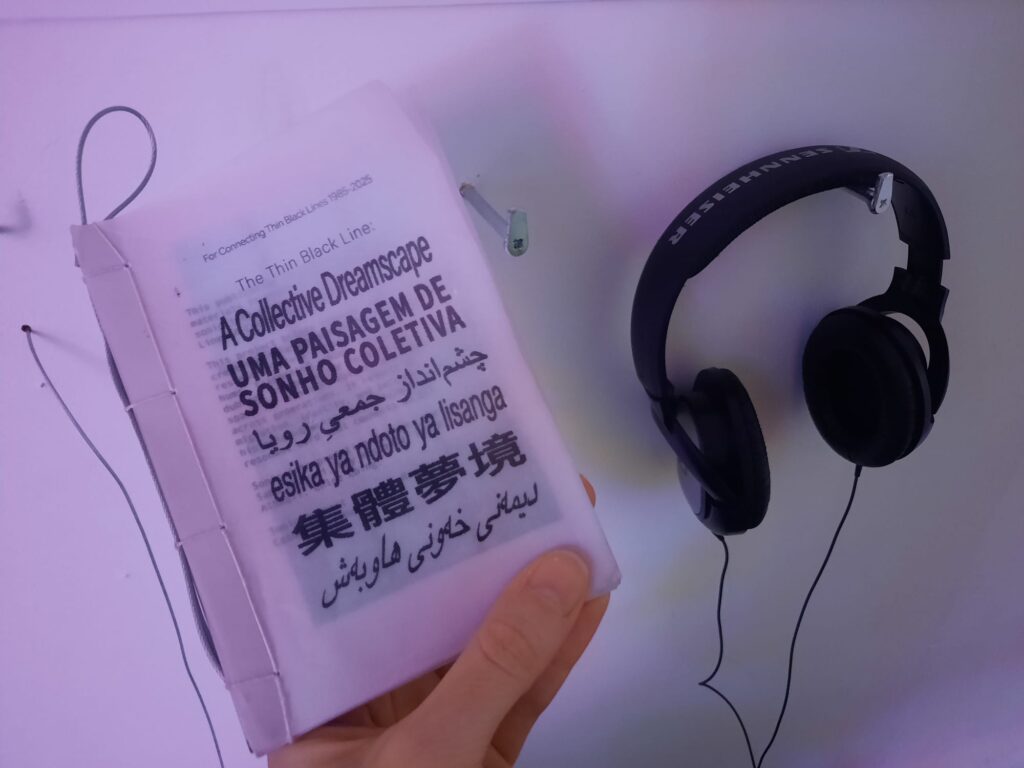

Reflecting on this exhibition forty years later, there’s enough distance to see what has changed and what has not. Himid again curates, bringing together works by the same group of artists, created over the past four decades (with only one or two exceptions, the works on display were made after the original exhibition). There are new commissions by Chila Kumari Burman and Marlene Smith. Many of the works come from Himid’s personal collection, showing what a key figure she continues to be in promoting art by Black and Asian women. Brenda Agard and Maud Sulter have unfortunately not lived to see this reappraisal of the earlier exhibition.

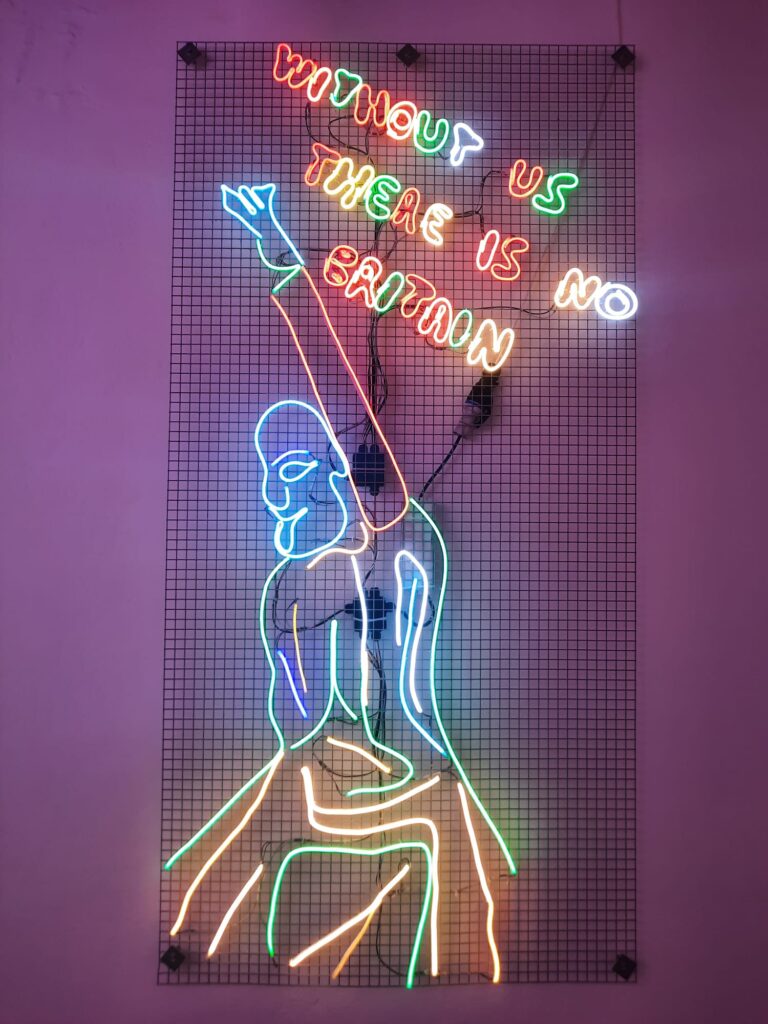

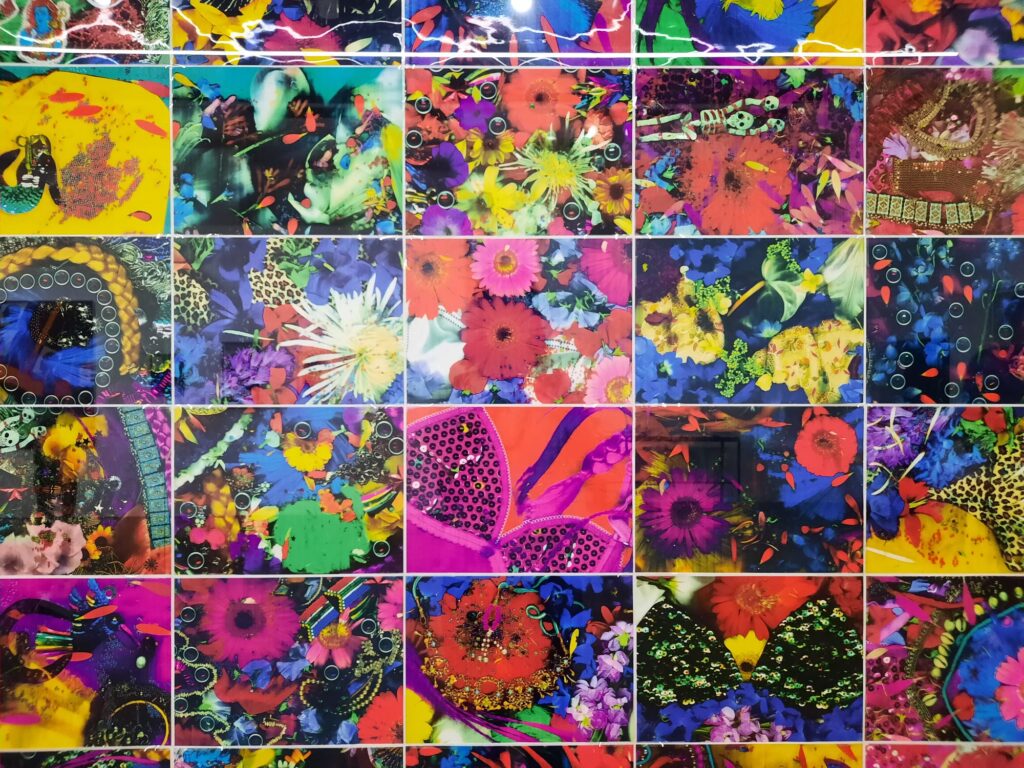

Often there are only one or two works by each artist. The earliest is from 1982 (Sonia Boyce) while the most recent, aside from the new commissions, is from 2024. As in the first exhibition, there is a particular focus on the realities of being Black and Asian women. For Claudette Johnson, this means women posed to take up space. For Marlene Smith, a reflection on family, biography and identity. Chila Kumari Burman tackles things head on, with one work entitled Protester – “without us there is no Britain”. Lubaina Himid comes back to a frequent theme of marginalised histories and geography with Venetian Maps: Shoemakers. It’s not part of this exhibition but I would also encourage you to check out Thin Black Line(s), 2011, which maps connections between the artists involved in her various curatorial projects. There’s an image of it here.

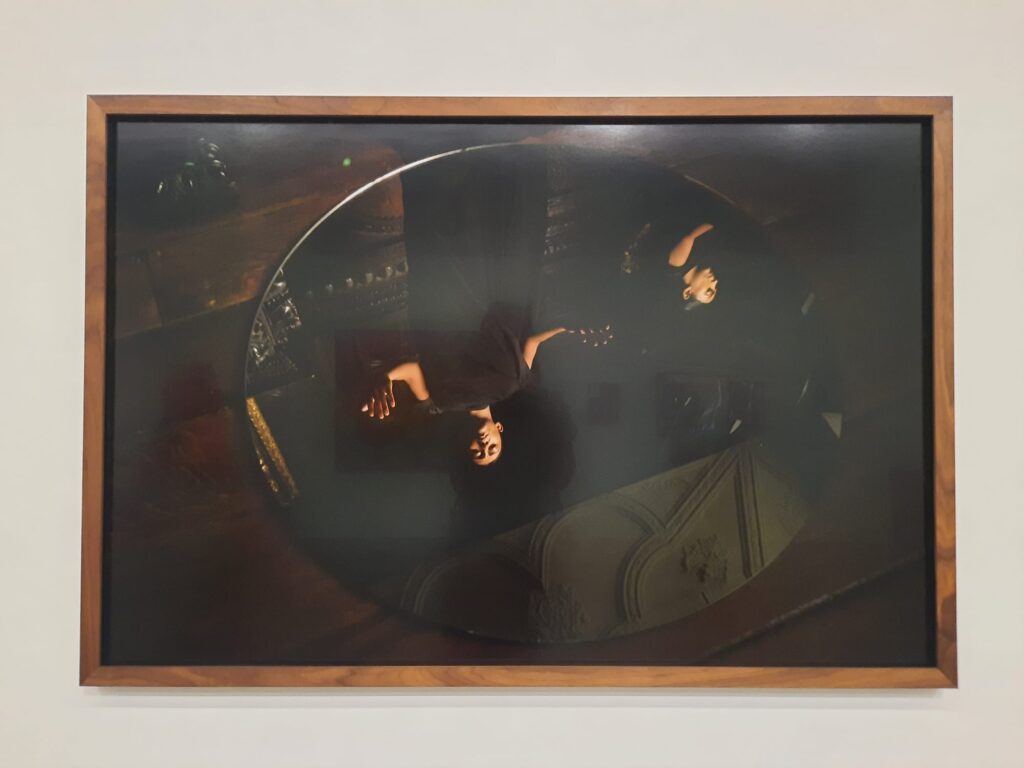

With a very discerning selection from each artist, the exhibition isn’t big. Burman’s bright neon works line a corridor. The main room holds the majority of the works. And there’s a small viewing room for Sutapa Biswas’s Birdsong, in which her young son encounters a horse in a dreamscape.

And the Future?

A lot has changed in the last forty years. A lot has not. Some of the women have won prizes. Some have worked different creative and non-creative jobs to support themselves as artists. A few curators, primarily outside London, took notice of The Thin Black Line and worked with Himid or other contributors on subsequent projects. And yet, as Himid notes in the materials for this exhibition “I’m uncertain if the original project to promote black women artists was completely successful because progress took so long and each of us, very different in practice and purpose, had to fly solo for many decades.”

Himid has again curated a wider programme to coincide with the exhibition. This gives some space to emerging artists to contribute and gain recognition for their work in turn. But this is primarily a backwards-looking exhibition. On the one hand it’s wonderful to see the work these women have made, their continuing presence in the art world despite the intersectionality of structural inequalities they have faced. On the other, the narrow selection is best for those with a good grounding in art who might know the artists already. For those who come at Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985-2025 with less prior knowledge, there is limited opportunity to understand how these artists might have evolved their approach in the intervening years.

Perhaps that’s not the point. Coming back to that letter Himid wrote to the other contributors right at the beginning, she made a point of using existing artworks. “The visuals you send should be of work you have, not specially done for this project – DON’T BREAK A LEG.” The point has always been a platform for artists who deserve one, not artists meeting our expectation of what their work, or this exhibition, should be. And on that count, Himid has once again succeeded.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Connecting Thin Black Lines 1985-2025 on until 7 September 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.