El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria (El Born Cultural and Memorial Centre), Barcelona

A fitting final stop in Barcelona, El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria offers a powerful glimpse beneath the city’s streets, revealing layers of history through archaeology, architecture, and memory.

One Last Wander

After my visit to the Museu Picasso, I still had a little time to spare before heading back to the hotel and on to the airport. On my first trip to Barcelona, I’d run out of time for both the Park Güell and the subject of today’s post: two sights that sat on my unfinished business list. Originally I’d thought to combine them, but with Park Güell’s early-morning sessions reserved for residents, I had to pair El Born with something else. Just a short walk away, it made perfect sense to combine with the Museu Picasso. But after the narrow, confined spaces of Barcelona’s old town, I wasn’t prepared for the scale of what I found.

Winding my way through the narrow alleys behind Carrer de Montcada, I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. Then the street opened up, and suddenly, there it was. El Born. Vast and imposing. The iron-and-glass frame of the old market hall seemed to rise out of nowhere, stretching wide across the square with quiet grandeur. It wasn’t quite on my must-see list first time around and yet here it was, stealing the spotlight.

I took a moment to sit on a bench outside, drink in hand, snack unwrapped, the whole building stretched out before me. It was one of those unexpected travel moments, when something you’ve planned to see is somehow different than you expected. Then, curiosity took over. Archaeology had lured me here (as ever). Now I wanted to see what lay beneath the surface.

A City Torn Open

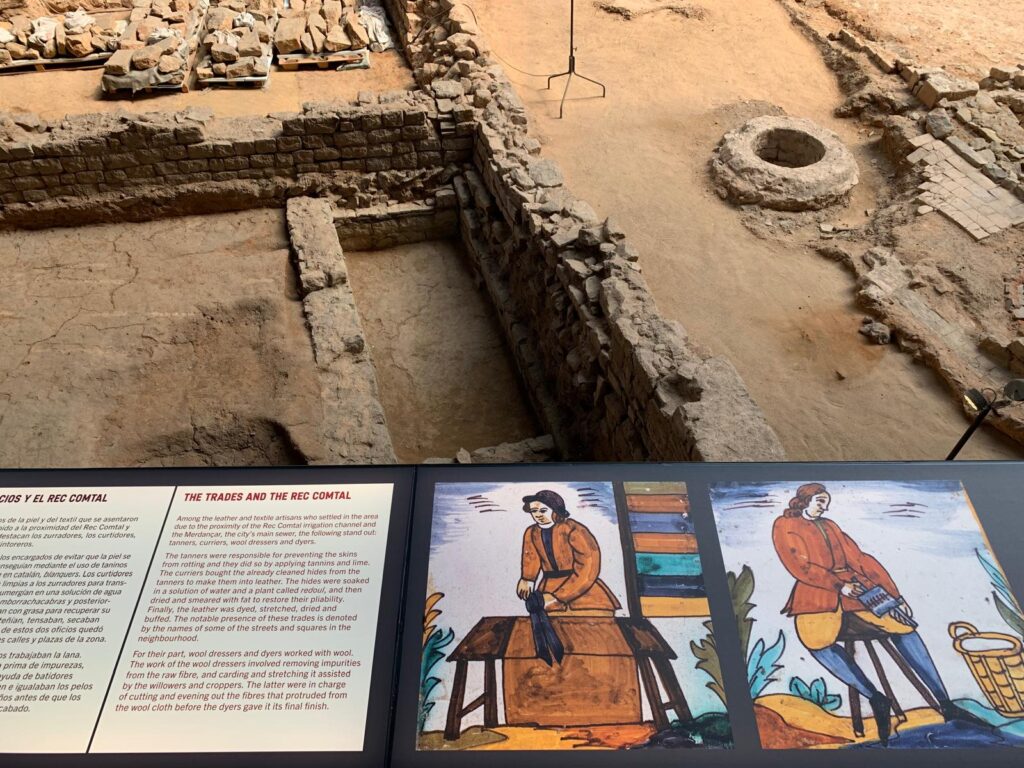

When you first step inside El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria, it’s hard to know where to look. The building itself is airy and impressive, a late 19th-century cast-iron market hall designed by Josep Fontserè. But your eye is drawn downward, to the archaeological remains beneath your feet. Here lies the neighbourhood of La Ribera, excavated and exposed: a labyrinth of streets, houses, shops and workshops, left much as they were when their residents were forced out over three hundred years ago.

This part of the city was destroyed in the aftermath of the War of the Spanish Succession, when Barcelona, after siding with the losing Habsburg cause, fell to the forces of Philip V in 1714. As punishment and to secure control, the new Bourbon king ordered a vast military citadel to be built (the largest in Europe at the time) and flattened whole swathes of La Ribera to make space. Around 1,000 buildings were demolished. Families were displaced, homes levelled, and a community erased. The citadel, designed to subdue rather than defend, stood as an ongoing symbol of repression and royal dominance over Catalonia.

Seeing the traces of everyday life (hearths, drainage channels, floor tiles still in situ) drives home the human cost of that decision. The architecture remains, steeped in political violence and cultural memory. The interpretation throughout the site is excellent, giving context to the war, the siege, and its enduring place in Catalan historical consciousness.

From Market to Memory Centre

The building that houses all this history has its own layered story. Constructed in 1876 to designs by Josep Fontserè, the Mercat del Born was one of Barcelona’s earliest examples of iron-and-glass architecture, part of a new wave of hygienic, rational market design following similar trends in Paris and London. It quickly became one of the city’s most important wholesale food markets, bustling with vendors and trade until it closed in the 1970s. For a time it stood unused, a grand but neglected space in the heart of the city.

It wasn’t until the early 2000s, when plans were underway to redevelop it as a new library, that the archaeological site came unexpectedly to light. What began as a construction project became a cultural moment. After intense public debate, plans for the library were shelved (pun intended). The city took the decision to preserve and showcase the ruins in situ, and to turn the site into what it is now: a centre for history, culture and memory. The building and the ruins thus exist in deliberate tension: iron and stone, past and present, loss and resilience. A bold decision to devote this much space to telling a mostly forgotten story.

The Visitor Experience at El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria

One of the real strengths of El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria is how accessible it is. Much of the site is free to visit. You can walk in off the street, follow the raised walkways above the excavated ruins of La Ribera, and spend as long as you like reading the generous interpretation panels that surround the space. There’s also a dedicated exhibition about the building’s time as a food market, giving insight into its 19th- and 20th-century past.

But if you want to deepen your knowledge and experience, there are a couple of ways to go further. Guided tours offer the chance to get down below the current street level and walk through the remains of the neighbourhood. A chance to stand where others lived, worked, and resisted. Or, you can do what I did, and buy a ticket for the permanent exhibition Barcelona 1700. From Stones to People.

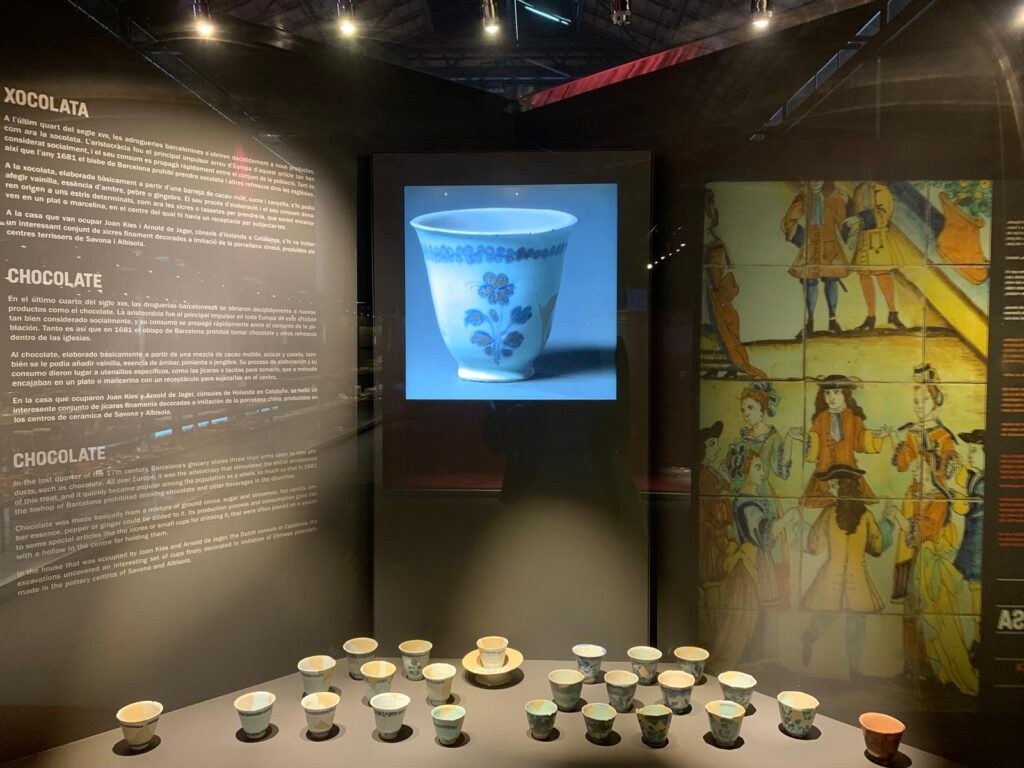

This exhibition takes up one of four internal spaces used for cultural activities (talks, temporary exhibitions and events) but it feels particularly well-matched to its setting. It brings some of the content quite literally back to the bare stones of the archaeological site. Hundreds of ceramic vessels, floor tiles, tools, ornaments and domestic items are laid out artfully, with thoughtful interpretation about their creation and use. A short introductory video helps to set the scene. A longer film near the end provides a more detailed historical background, alternating between languages.

It pairs nicely with the experience outside. A way of adding texture and human detail to the daily lives that were lived here. You come away not just with a sense of what the city lost, but of the people it was made up of.

Final Thoughts on El Born (and Barcelona) (and Archaeology)

I don’t regret any of the places I prioritised on my first visit to Barcelona. You’ve got to start somewhere, and the city has more than enough headline attractions to fill a first-time itinerary. But I’ve really appreciated some of the places I’ve seen this time around. They’ve deepened my understanding of the city: its art, its history, its quiet corners and layered identities.

On this trip I’ve revisited a favourite in the form of the Sagrada Família. I’ve looked out across the city from the heights of Gaudí’s Park Güell. I’ve challenged my own expectations at the Museu Picasso Barcelona, and delved into the city’s religious past at the tranquil Reial Monestir de Pedralbes. Each stop has added another facet.

And this, El Born, feels like a fitting place to finish. Long-time readers will know how much I love archaeology. I’ve sought out almost identical sites around the world. There’s the Museo de Sitio Bodega y Quadra in Lima, also a free, extensive and centrally located archaeological site. The Settlement Exhibition in Reykjavík. Even the underground section of the Museu d’Història de Barcelona. These places always draw me in.

I find them very grounding (pun intended?). For all that cities can start to feel the same, especially the well-touristed ones, getting under their skin, sometimes literally, helps reveal the long histories, deep ruptures, and curious continuities that have shaped them. I hope my explorations of city archaeology continue for a long time to come.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.