Feel the Sound – Barbican, London

I like the idea behind the Barbican’s Feel the Sound, perhaps a little more than the actual experience of visiting.

Feel the Sound

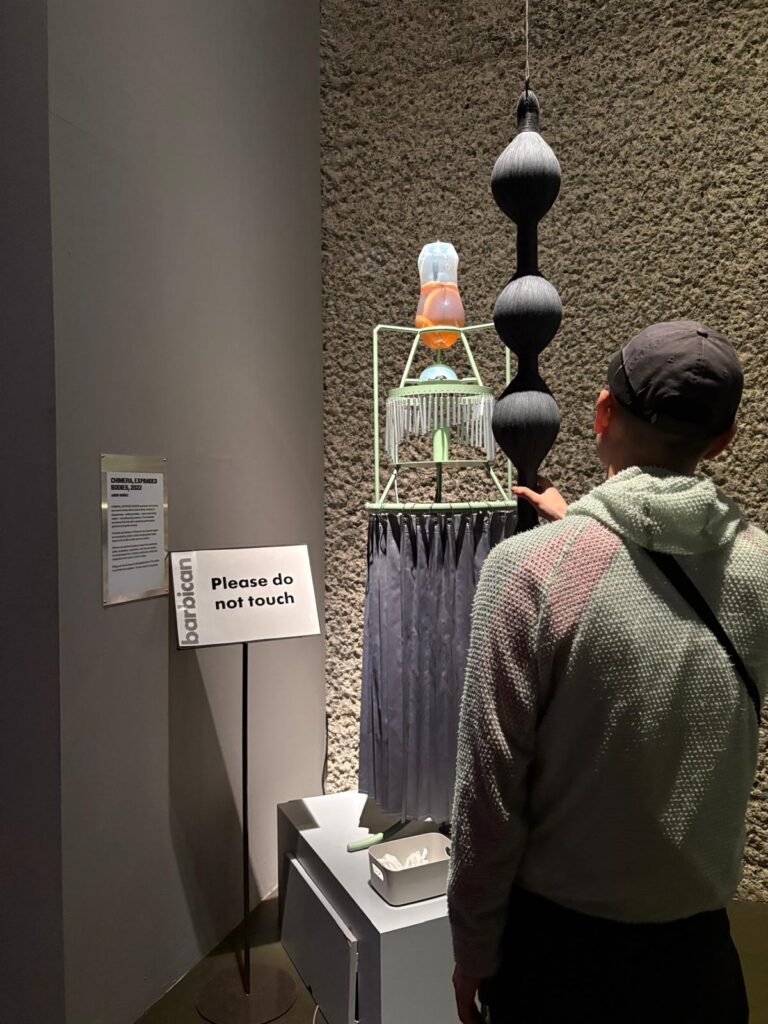

The Barbican bill their current exhibition Feel the Sound as an “exhibition experience on a different frequency.” This is a clever play on words, but also mostly true. Feel the Sound takes visitors on a journey through eleven different stations which transform sound from an auditory to a multisensory experience. I’ve always had a soft spot for exhibitions where you can do, that prioritise interaction and discovery over passive observation. And in that respect, this one is immediately compelling. From the start, it invites tactile, spatial, and physical modes of engagement: sound is translated into vibration, gesture into harmony, data into choreography. Technologies that might otherwise seem alienating (neural feedback systems, real-time AI composition, motion tracking) are deployed in ways that feel exploratory and open-ended. Less about spectacle than about making the invisible perceptible.

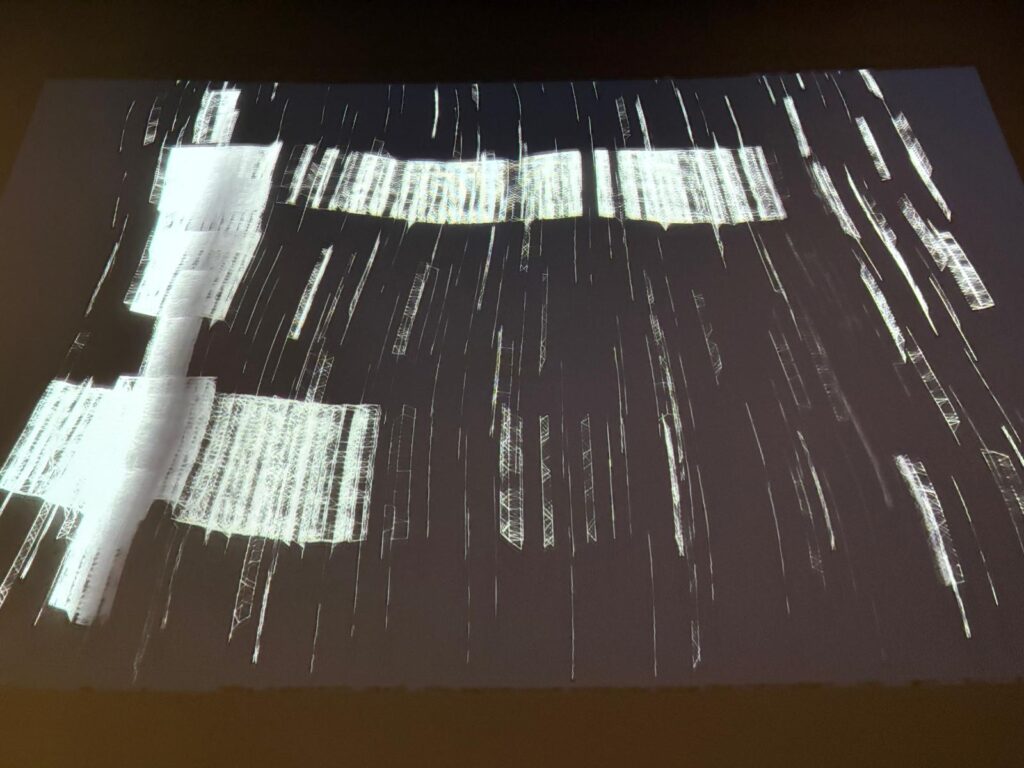

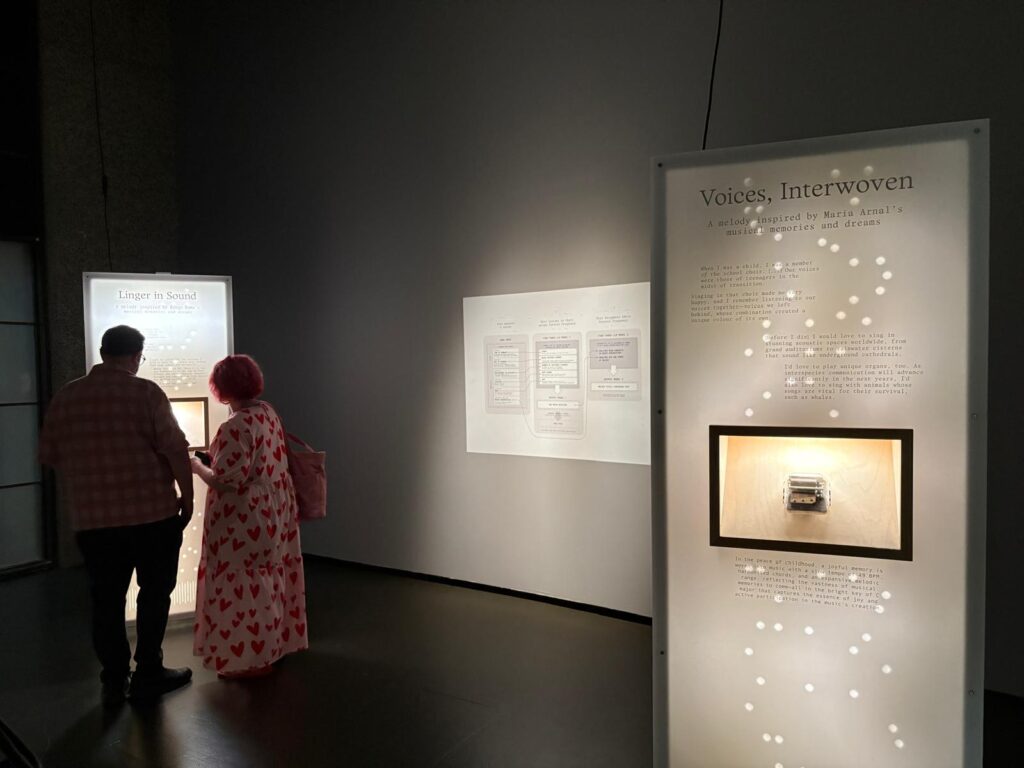

The exhibition’s strength lies in this premise: that sound is not just one thing, but is capable of crossing sensory thresholds. In places, it achieves this with real clarity. Miyu Hosoi’s Observatory Station, built around multi-channel recordings layered with environmental noise, turns the visitor into both source and receiver. Other works, like Forever Frequencies by Domestic Data Streamers, use AI in a more speculative register, generating sonic responses to prompts submitted by visitors. This helps to lend the show a self-reflexive tone, as if the works are listening back. There’s a lineage here that’s recognisable from 180 Studios: a shared emphasis on imagined digital futures, embodiment, feedback, and the role of the viewer. What distinguishes Feel the Sound is that this interactivity isn’t a side effect but the conceptual core. The works aren’t complete without us.

Embedding Inclusivity and Accessibility

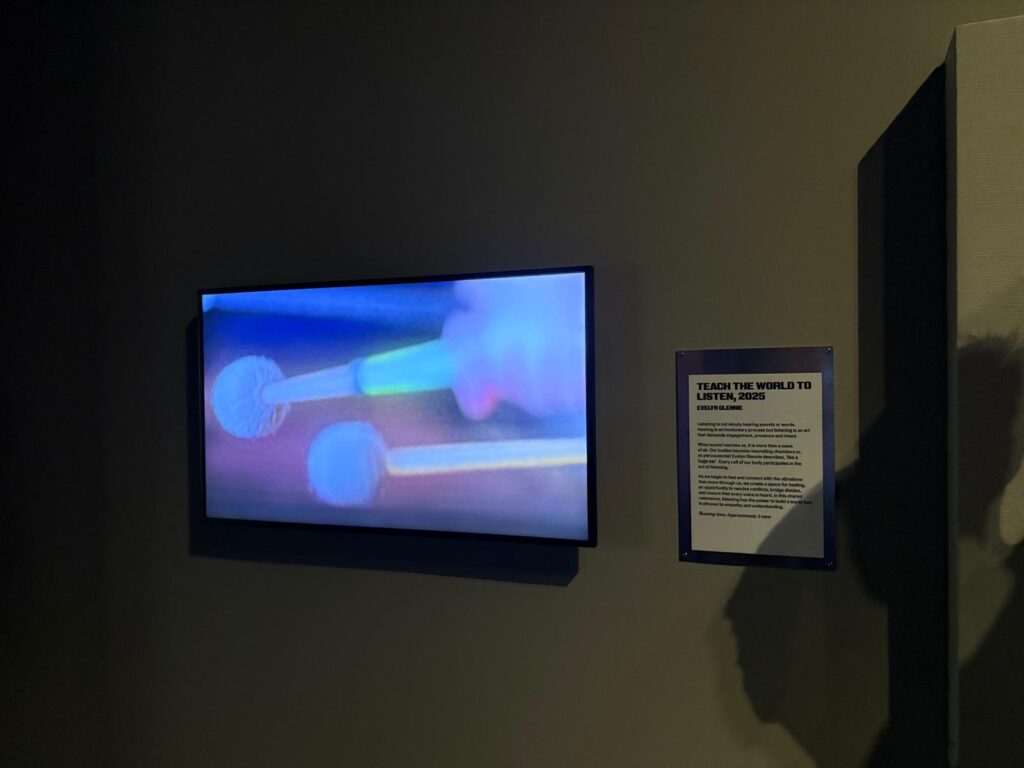

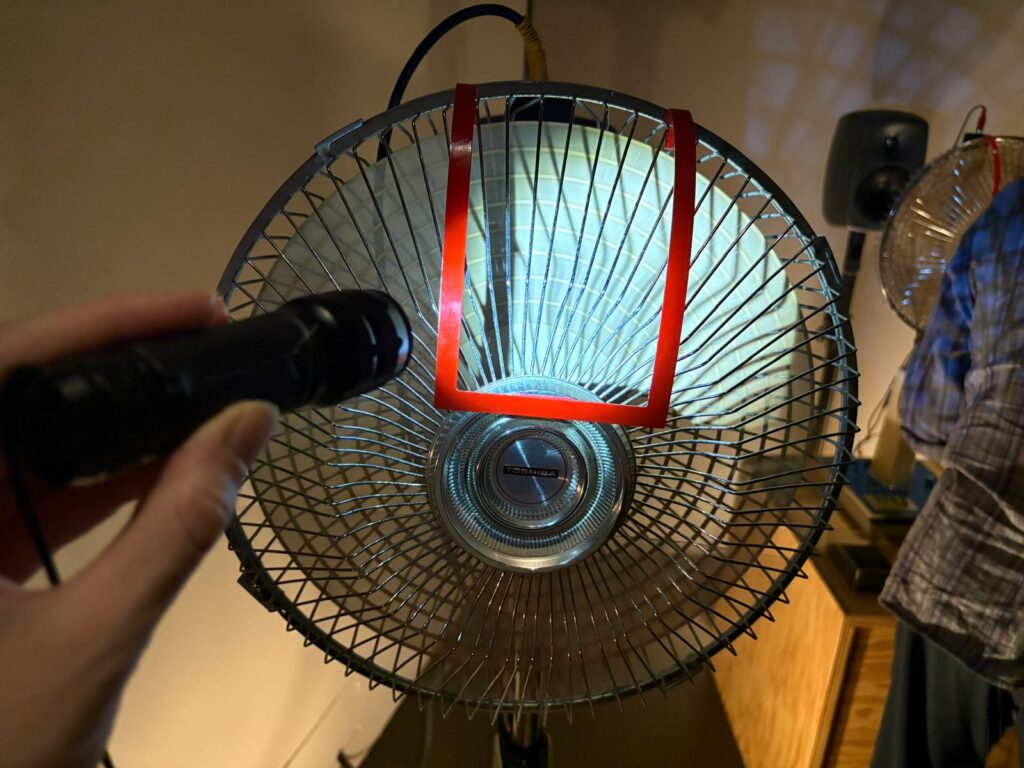

What also stands out is the exhibition’s consistent emphasis on accessibility as a creative principle as much as a practical consideration. Feel the Sound foregrounds tactile and visual modes of engagement, and in doing so opens itself up to audiences who are often sidelined by sound-based or screen-based work. Much of what’s on display here can be experienced without relying on hearing or sight. Vibrations embedded in benches, low-frequency bass platforms, responsive lighting, data visualisation that’s both visual and auditory: all help to reframe who the exhibition is for. It’s a rare thing to encounter a show that feels genuinely multisensory, rather than simply offering a few accommodations appended at the end. Raymond Antrobus’s Heightened Lyric, installed outdoors on the Lakeside Terrace, is emblematic in this regard. The work combines BSL poetry, silent kites, and rhythm communicated through movement alone, shifting the centre of gravity away from language altogether.

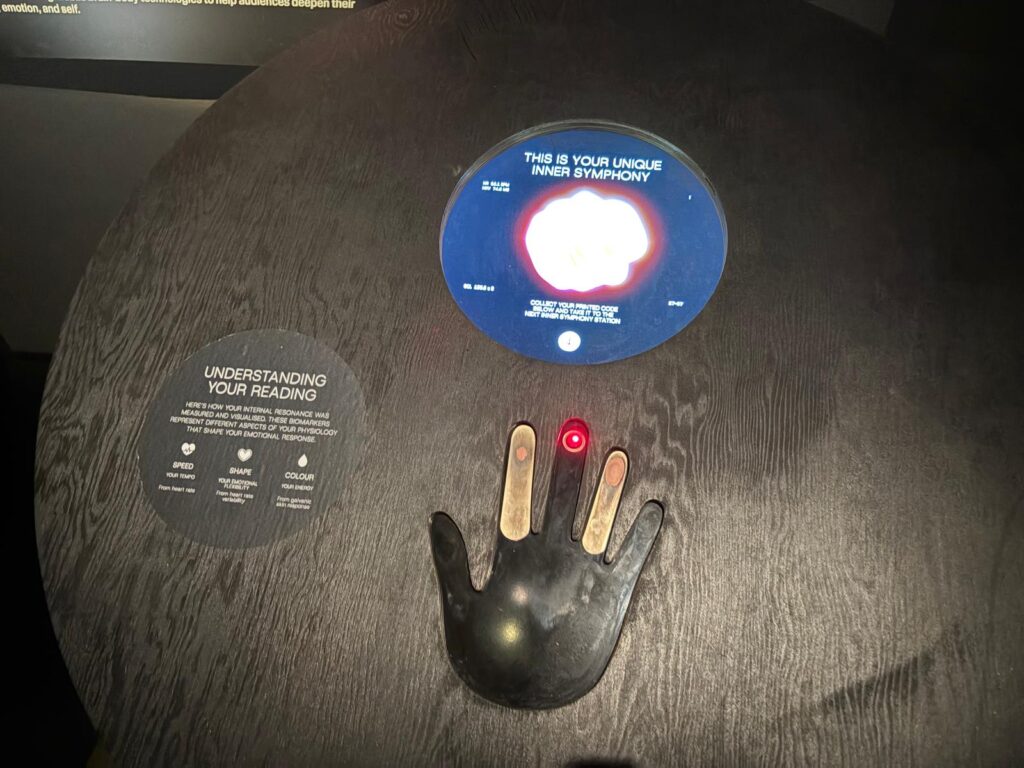

This attention to inclusivity is thus ingrained in the exhibition. It alters the terms of engagement across the Barbican Curve and supplementary spaces, producing a kind of levelling effect. Instead of privileging any single sensory mode, the works ask us to move between them. In that sense, the exhibition avoids the pitfalls that sometimes haunt immersive shows (especially those working with new technology) where interaction is mediated entirely through slick screens or expensive interfaces. By contrast, Feel the Sound is physically grounded. Even the more overtly technological works, like Your Inner Symphony (Kinda Studios and Nexus Studios), which visualises biometric data as a personalised musical score, retain a human scale in their presentation.

There’s also a strong undercurrent of play here. You’re invited to press, move, balance, speak, listen, lie down. If anything, the problem is not that the show lacks points of access, but that there are almost too many, and you may not get to try them all.

Interactivity as a Strength and a Weakness

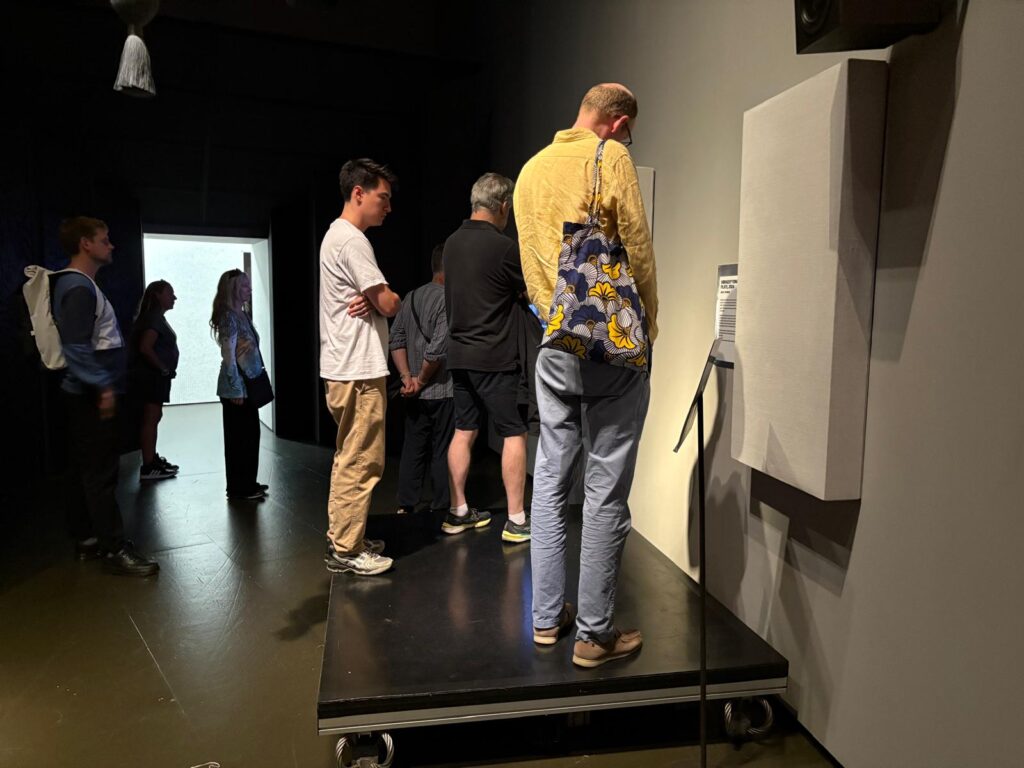

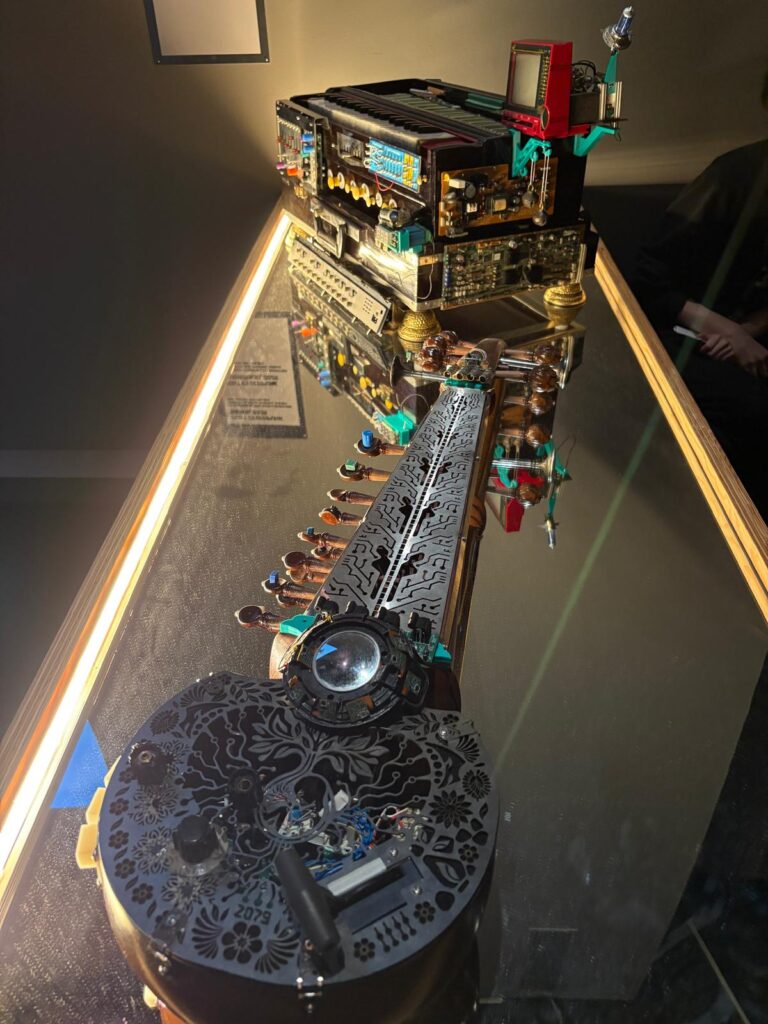

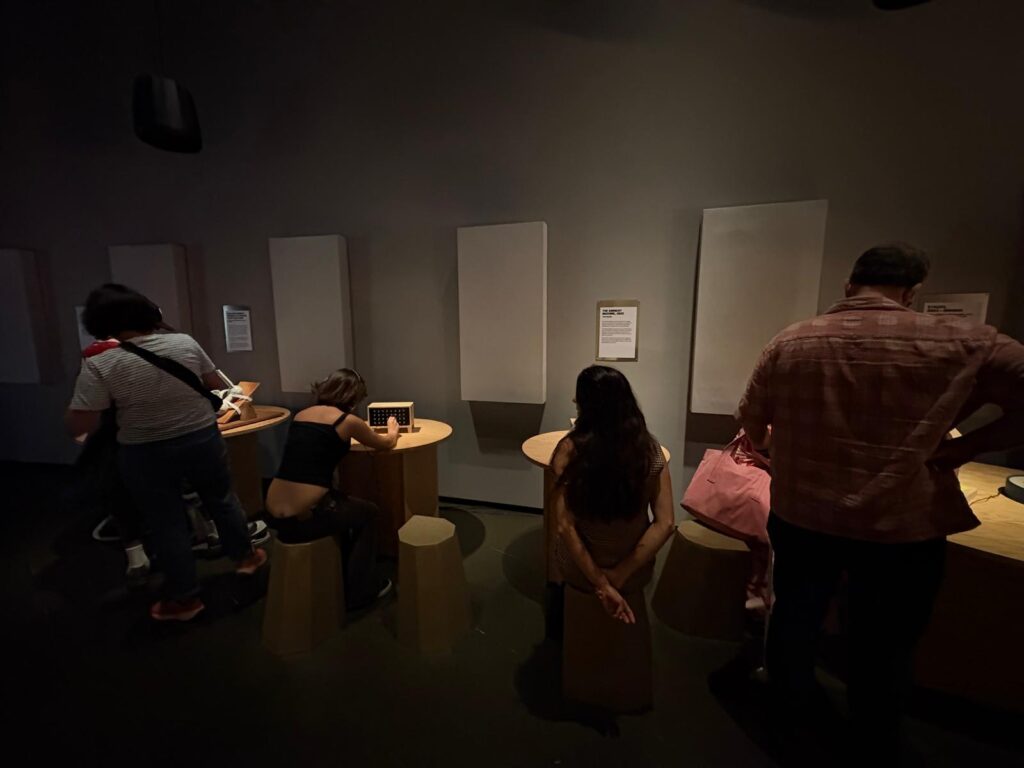

The exhibition’s interactivity – its greatest strength – also creates its most visible problem. Several works require individual participation, often one person at a time. These include Your Inner Symphony, Resonance Continuum (Elsewhere in India), and the spaces entitled Embodied Listening Playground and Sonic Machines Playground. As a result, visitors spend more time queuing than engaging, especially during busy periods like school holidays. In some cases, you end up watching others interact instead of doing it yourself. That undermines the work. These pieces were designed to be experienced directly, not observed from the sidelines.

There’s a mismatch here between intention and scale. The Barbican is a major London venue with a large and unpredictable audience. But these works demand intimacy, focus, and time: conditions the space can’t always provide. Feel the Sound asks for slowness, attention, and physical presence, but delivers a fragmented rhythm of stops and starts. The exhibition doesn’t collapse under this tension, but it does stall. I found myself drifting between active engagement and passive detachment, which was clearly not the point.

This friction isn’t new (it echoes issues I’ve seen in other immersive shows, particularly those where you’re waiting for a VR headset) but it feels sharper here. The works are ambitious and carefully built. They invite deep, personal engagement. Yet their accessibility is undercut by the basic fact of too many people, not enough space, and limited time. The result is an exhibition that wants to be open, but ends up excluding through delay.

Extension Beyond the Exhibition Space

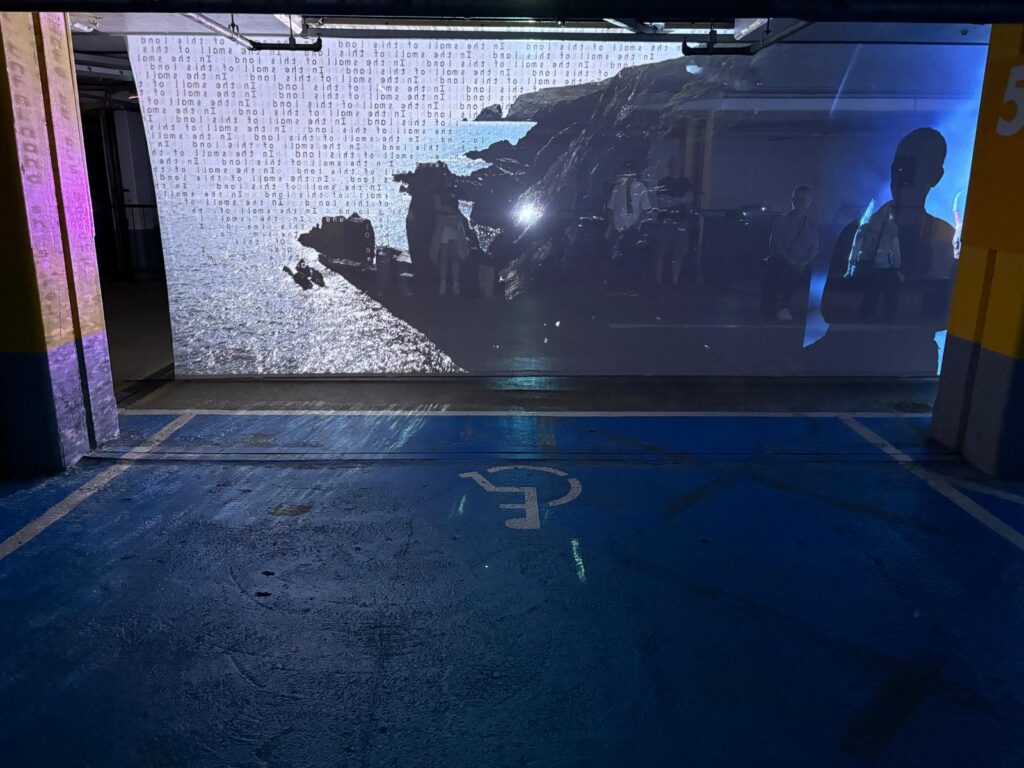

The exhibition extends beyond the Curve into the Barbican’s more liminal spaces: car parks, terraces, corridors. This is a smart move. It opens the concept to people who might not have come intentionally and reframes the building as part of the soundscape. Joyride by Temporary Pleasure, the second installation in the car, park stood out for me. Dense, raw, and industrial, it transformed a dead space into something electric. It reminded me immediately of Peaceophobia at Here East, both in its subculture subject matter and in its use of non-gallery architecture to build atmosphere.

These interventions are among the most effective. They activate spaces that usually feel peripheral. At its best, this tactic creates porous boundaries between public space and curated experience. It’s also an effective hook. You hear something before you see it. You follow the echo. You’re drawn in.

But this spatial sprawl also introduces problems. The pacing of the exhibition suffers as the transitions become more fragmented. Some moments feel ad hoc or underdeveloped. At times, I lost the sense of a curatorial arc. There’s also a question of fit. The Barbican’s concrete, institutional geometry doesn’t always sit comfortably with the show’s looser, more bodily aesthetic. In several moments, I found myself thinking this would have landed more fully at 180 Studios. Not because the work is weak, but because the space doesn’t quite yield.

Still, the ambition is clear. Feel the Sound wants to remake how we experience sound physically, socially, architecturally. Even when uneven, that feels like something worth exploring.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Feel the Sound on until 31 August 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.