Museu Picasso Barcelona

On my final morning in Barcelona, I made a spontaneous visit to the Museu Picasso Barcelona, and left unexpectedly impressed.

A Final Morning and a Familiar Name

It was my last day in Barcelona. I had a few hours before I needed to head to the airport, and time to fit in one or two more stops. Originally, I had thought I might visit the Park Güell plus a museum. But early morning hours are reserved for Barcelona residents: something I completely support, but which ruled out that option for me.

I knew I wanted to visit one more place that had been on my list since my first trip. That’ll be my next post. But what to pair with it? I was in that slightly frantic pre-departure mood, checking opening times and distances, trying to make the most of every moment. Maybe the Museum of Prohibited Art? Sounds interesting. But can I make it to both in time? And then I thought: why fight it? If I was going to El Born Centre de Cultura i Memòria, why not pick something nearby? Barcelona isn’t short of museums.

So I decided on the Museu Picasso Barcelona. It wasn’t high on my list, despite a firm recommendation from a friend. Mainly because Picasso never feels like a rarity. He’s in every major collection. I’ve seen temporary exhibitions, and I’ve been to museums dedicated to him in both Málaga and Paris. Would Barcelona have something different to offer? As it turns out, yes.

Picasso and Barcelona – A Complicated Affection

Picasso was born in Málaga, but Barcelona was the city where he came of age. His family moved there in 1895. Picasso was only a teenager, but already serious about his work. He trained at the Barcelona School of Fine Arts from 14 years of age, spent formative years in the Gothic Quarter, and found early inspiration in the café culture of Els Quatre Gats. This was where he first exhibited, where he read, drank, sketched, argued. Though he left young (moving on to Madrid, then Paris) Barcelona remained emotionally important. It was, he once said, the city where “everything began.”

In later years, though, his relationship with Spain was complicated. He refused to return under Franco’s regime and publicly opposed the dictatorship. The most famous result was Guernica, painted in response to the Fascist bombing of civilians during the Spanish Civil War.

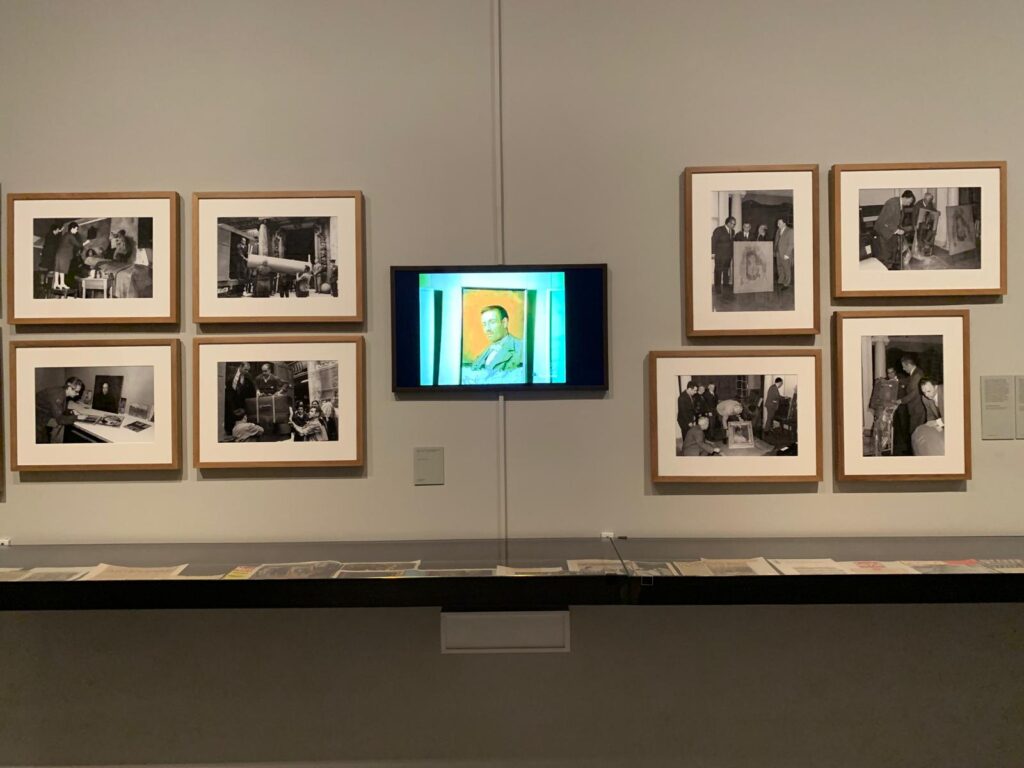

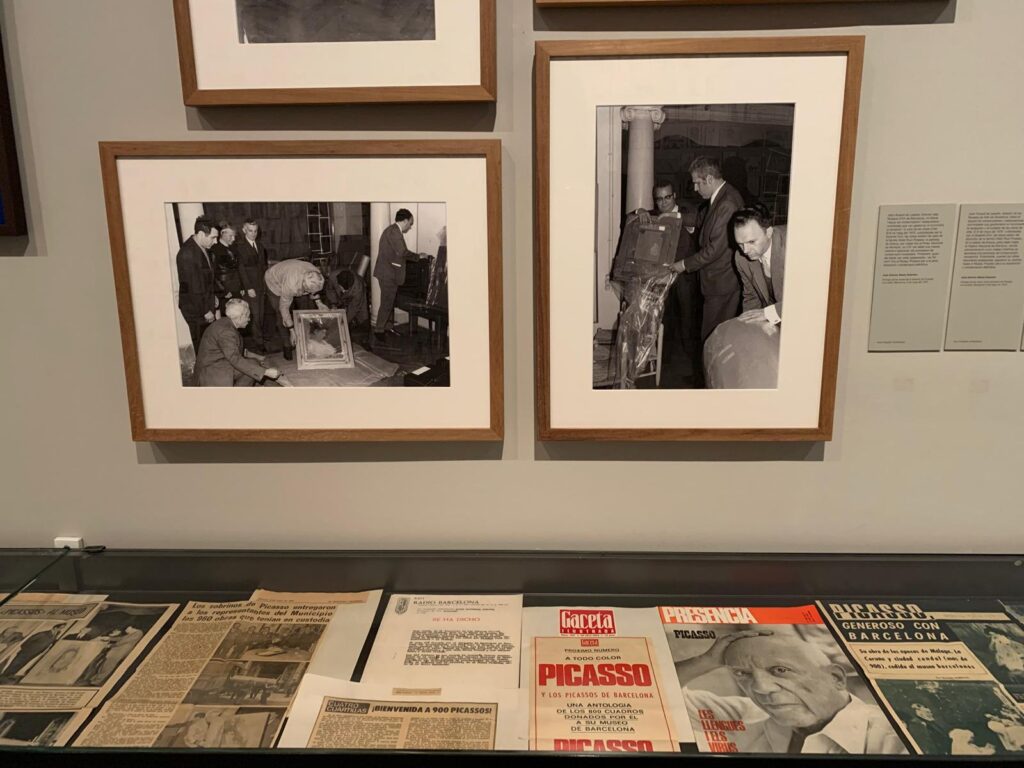

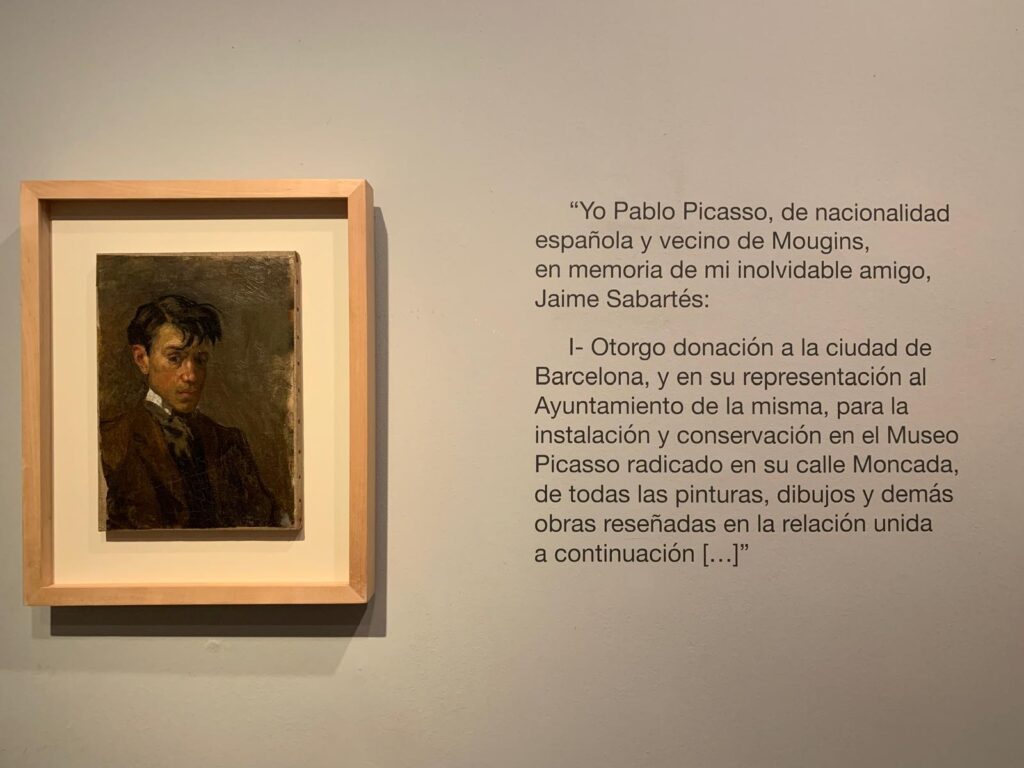

Picasso had long supported the idea of a museum in Barcelona. But for a time, it wasn’t politically possible. The idea re-emerged in the early 1960s. The museum was discreetly founded under the name Col·lecció Sabartés – named not for Picasso, but for his close friend and secretary Jaume Sabartés. This gave the project enough cover to proceed, even under Franco. Sabartés had been collecting Picasso’s work for years, and donated the core of the first collection. Picasso himself added hundreds more pieces. The result wasn’t just a grand retrospective, but something far more personal.

A Museum in Five Palaces

The Museu Picasso is housed not in one building, but five linked medieval palaces. You’ll find them nestled together on Carrer de Montcada in the Gothic Quarter. They’re easy to overlook from the street, but inside, the scale opens up. There are vaulted ceilings, stone staircases, delicate balconies, and internal courtyards. The oldest of the buildings dates back to the 13th century. This setting gives the museum a different feel from other Picasso collections. It’s not sleek or imposing. And definitely not a white cube. It’s intimate, and oddly quiet.

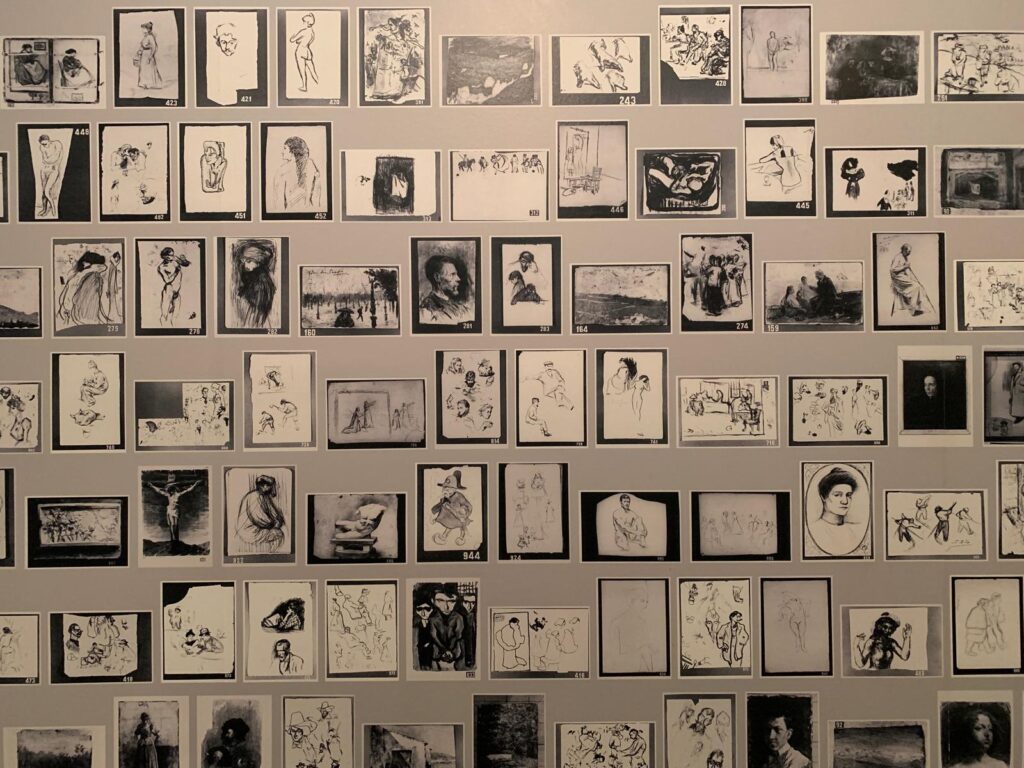

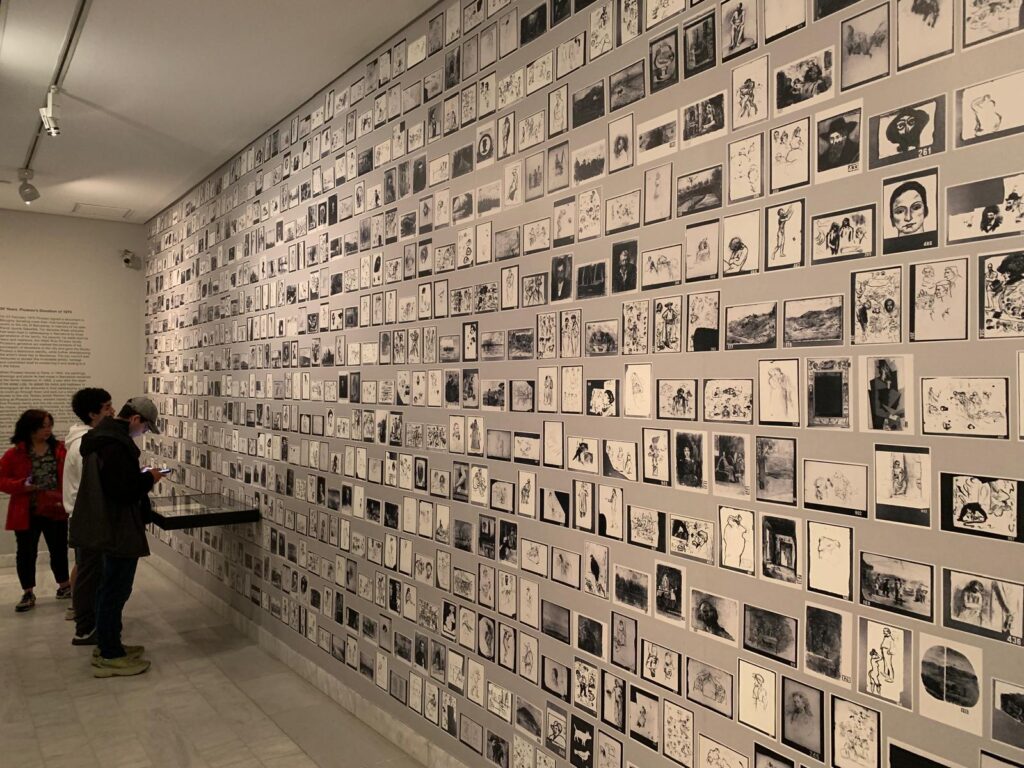

The original donation began with around 600 works, mostly from Picasso’s youth and early training. These early paintings are highly accomplished, but far from the Cubist style many associate with him. In 1970, for his 90th birthday, Picasso donated over 900 more works to the museum. He chose them himself, with characteristic control over how he wanted his legacy framed. The additions weren’t crowd-pleasers. There were hundreds of drawings, notebooks, ceramic pieces and unfinished sketches. They form a rare record of his process: scribbled notes, repeated studies, and stylistic experiments.

In the decades since, the museum has continued to grow. It now houses over 4,000 pieces, including key series like the Las Meninas variations. All this is woven through the labyrinthine corridors of these old buildings. The layout isn’t linear: you find yourself doubling back, turning corners, going up and down stairs. That sense of movement mirrors the work. Sometimes chaotic, but always pushing forward.

A Collection With a Point of View

The Museu Picasso doesn’t try to be the definitive Picasso museum. Instead, it offers something more personal and sharply curated. It begins by setting the scene. Picasso’s early years in Barcelona, and the story behind the museum’s creation. This gives it a more intimate feel than many large institutional collections. Visitors aren’t overwhelmed by quantity, but invited to focus.

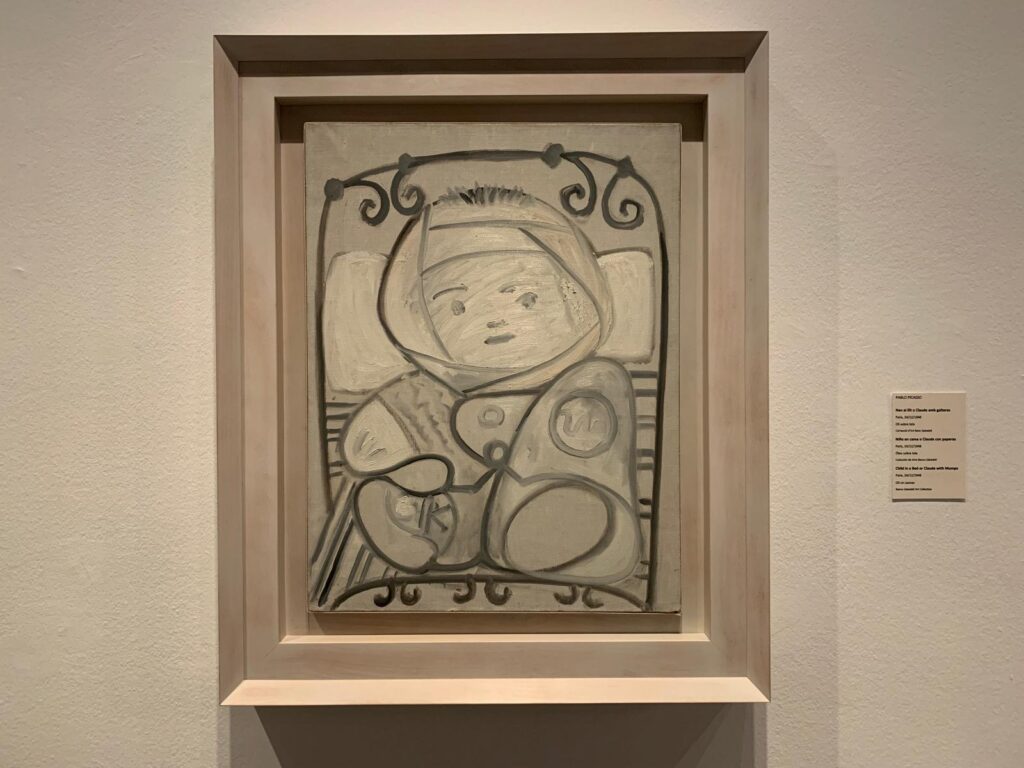

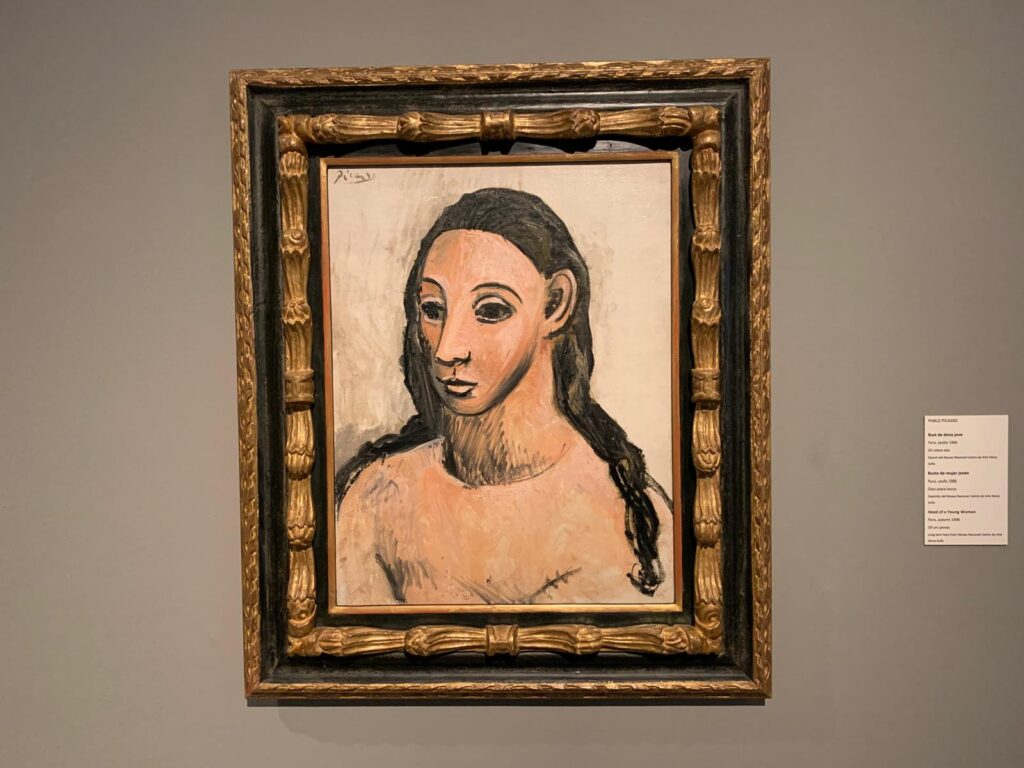

The collection is particularly strong on early work. These paintings show Picasso not as a rebel, but a gifted traditionalist. From a very young age, he was working in oil. The pieces are often small, dark, and impressive. There’s something moving about seeing the brushstrokes of a teenager already better than most adults. Many of these works come from family donations. That adds another layer of context: what they chose to keep and why.

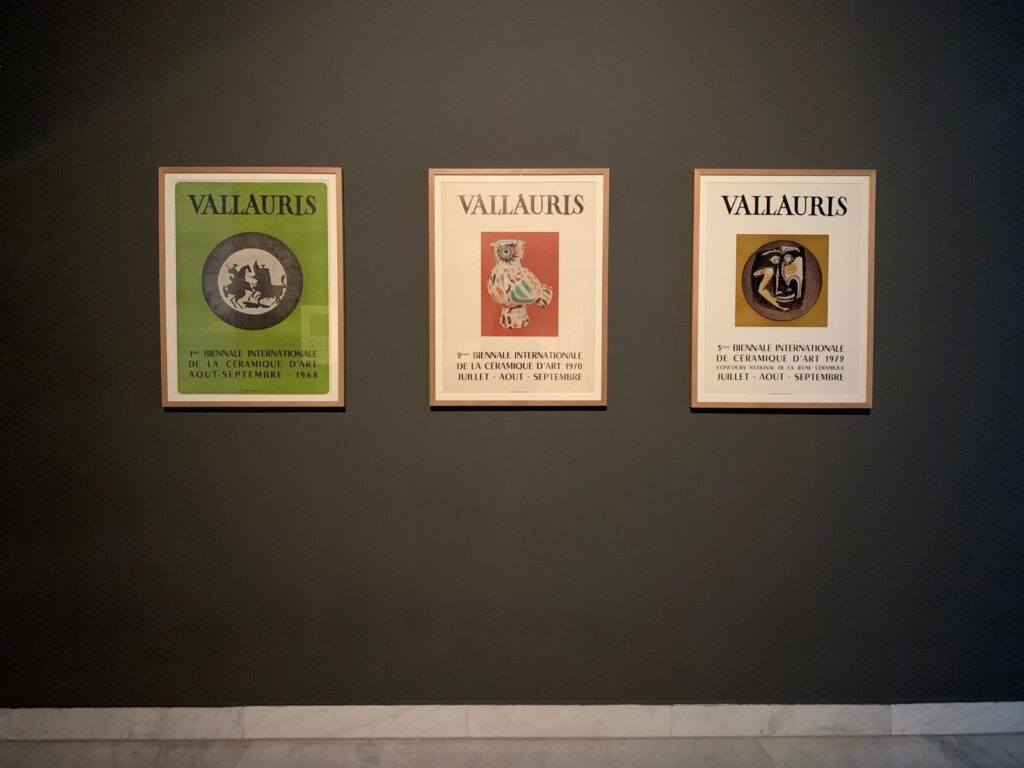

A standout section is the museum’s ceramics collection. It’s presented separately, and rightly so. These works are playful, bright, and full of humour. Plates become faces. Vases sprout animals. They show Picasso at his most relaxed and experimental, clearly enjoying the medium.

By the time you reach the later galleries, you’ve had a tour through several different artistic identities. The Blue and Rose Periods, of course, but also Picasso as student, son, collaborator, and craftsman.

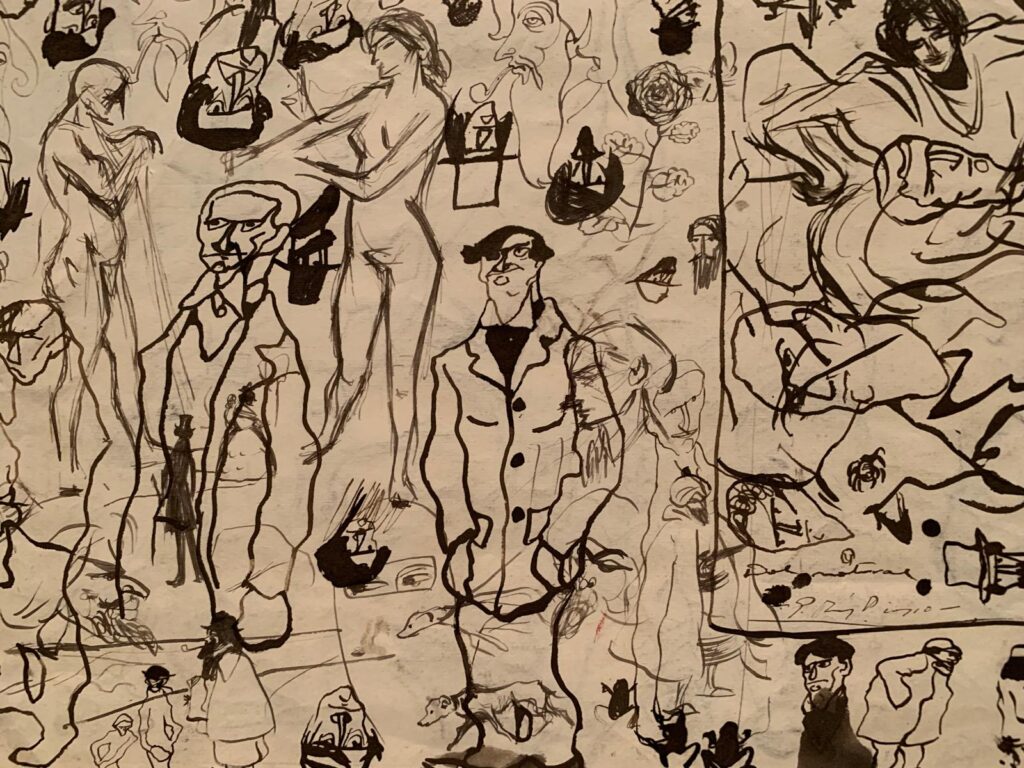

The Restless Mind of an Artist

As the galleries progress, we see Picasso moving into more fragmented, repetitive, and self-referential modes. His work becomes about process as much as product. Ideas evolve over dozens of variations. Take the Las Meninas series. Inspired by Velázquez, Picasso reworks it again and again, changing angles, colour, composition. It’s like watching him think out loud, using his brush as a means of problem-solving. These repetitions are some of the museum’s most compelling rooms. They show Picasso not as a genius dashing off paintings, but as a disciplined worker. Each painting builds on the last. It’s a rhythm, almost a ritual. One image gives birth to another, and another.

Another series focuses on the view from a window in the South of France. In each painting, he’s testing new ways to see. This is what I admire most in Picasso: the sheer momentum of his creativity. He never sits still. Even when the works are less striking individually, they matter as part of the larger engine.

But for all its strengths, the museum sidesteps the harder questions. Picasso’s treatment of women, for example, or his ego, or how much space he occupied in the art world. None of that is absent from his work, but it’s not addressed directly here. We see brilliance and productivity. We don’t see pain, control, or consequences. The Museu Picasso doesn’t ignore the man, but it mostly shows him from his best angles. A fitting tribute, perhaps. But a partial one nonetheless. And if we’ve learned anything from Cubism, it’s that you have to see all the angles at once to really understand the whole.

The Museu Picasso Barcelona, A Museum That Might Just Convert You

A friend once told me that the Museu Picasso Barcelona could turn even Picasso-sceptics into fans. I think she might be right. This is a well-paced, thoughtfully curated museum that starts quietly and builds in momentum. From the early sketches and sombre tones of a classically trained teenager, through ceramics, portraits, and series of paintings, you get a real sense of Picasso as a constantly evolving artist. The museum focuses on his process as much as the finished pieces. You see him work and rework ideas, pushing a subject until he’s explored every angle.

The building itself adds to the experience. Spread across several adjoining Gothic palaces, the museum feels expansive without being overwhelming. There are elegant architectural details throughout, nodding to the layered history of the space. The transitions between exhibition rooms and buildings are fluid, giving a sense of movement through both time and art. You could easily spend half a day here, taking in the museum, shop, and restaurant.

When I left, I stepped straight back into the winding alleys of the Gothic Quarter and on to my next destination. I had the feeling I probably don’t need to see another entire museum dedicated to Picasso. Surely that’s enough now! I understand Picasso and his art! But then again, I’ve said that before. And look where it got me.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.