Kerry James Marshall: The Histories – Royal Academy, London

Kerry James Marshall’s The Histories examines Black experience, identity, and art history through striking, richly pigmented paintings.

Kerry James Marshall

2025 has been a year of discovering new (to me) contemporary artists in favourite galleries. I really enjoyed Noah Davis at the Barbican earlier in the year. There was Jenny Saville at the National Portrait Gallery. Hew Locke at the British Museum. Some of these artists I knew something about but hadn’t had the opportunity to understand their work in detail. Others were complete discoveries.

Kerry James Marshall was probably more in the former category. I knew of him as an artist, but didn’t know much about his work. So the current exhibition at the Royal Academy was a great opportunity to learn more. And, as frequently happens on the Salterton Arts Review, I think a quick overview of Marshall’s biography is a good place to start in sharing that with you.

Marshall was born in 1955 in Birmingham, Alabama. He spent time in childhood in Los Angeles, and has lived more recently in Chicago. His political sensibilities started to develop early. The family home in LA was near the headquarters of the Black Panthers. And he moved to the Nickerson Gardens public housing project in Watts in LA just a few years before riots broke out there.

Marshall began exploring art at school, starting with figure drawing. In 1978, he earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Otis College of Art and Design in LA. As well as pursuing his own artistic practice, Marshall was a professor for many years at the School of Art and Design of the University of Chicago, and was named by Barack Obama on the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities in 2013. He still lives and works in Chicago, Illinois.

The Histories

The Histories is a great title for this exhibition, and also a statement of intent. Not one history, the histories: multiple. What are these histories? And what does it tell us about Marshall, and also about the Royal Academy?

Let’s start with the idea of history as a plural concept. It feels as though we’re finally beginning to accept that there is no single, definitive narrative. That history is shaped by who tells it, whose experiences are recorded, and whose are erased. In the context of the Royal Academy, this feels particularly significant. As an institution with its roots in the eighteenth century, the RA has not always been quick to confront colonial legacies or questions of representation. But in recent years, through exhibitions such as Entangled Pasts and Souls Grown Deep Like the River, there’s been a conscious effort to open up the canon, to make space for artists and stories that had previously been left out.

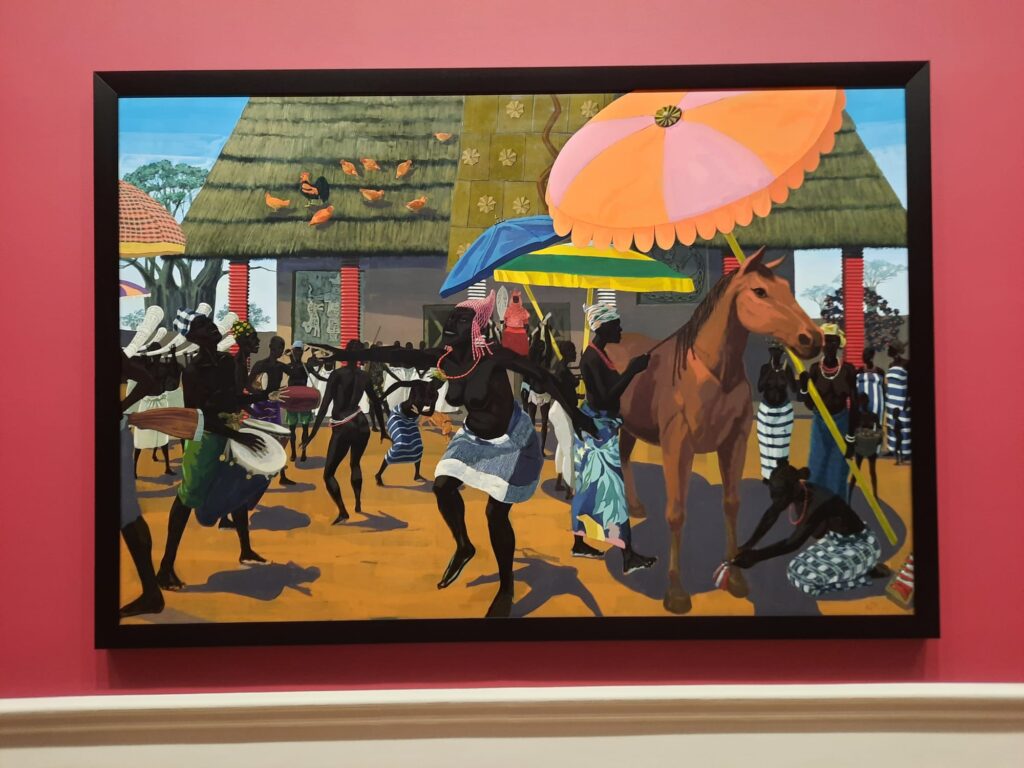

Marshall’s The Histories fits squarely within that project. It’s both a continuation of his own lifelong exploration of what it means to be Black in America, and a dialogue with the artistic establishment that once excluded Black artists and objectified Black subjects. Across this exhibition, two forms of history seem to come through most strongly. One is social: a sustained, thoughtful engagement with Black experience, the politics of exclusion, and the construction of identity. The other is art historical: Marshall placing himself, deliberately and skillfully, within the lineage of Western art. It’s that interplay of the personal and political that gives the exhibition such depth.

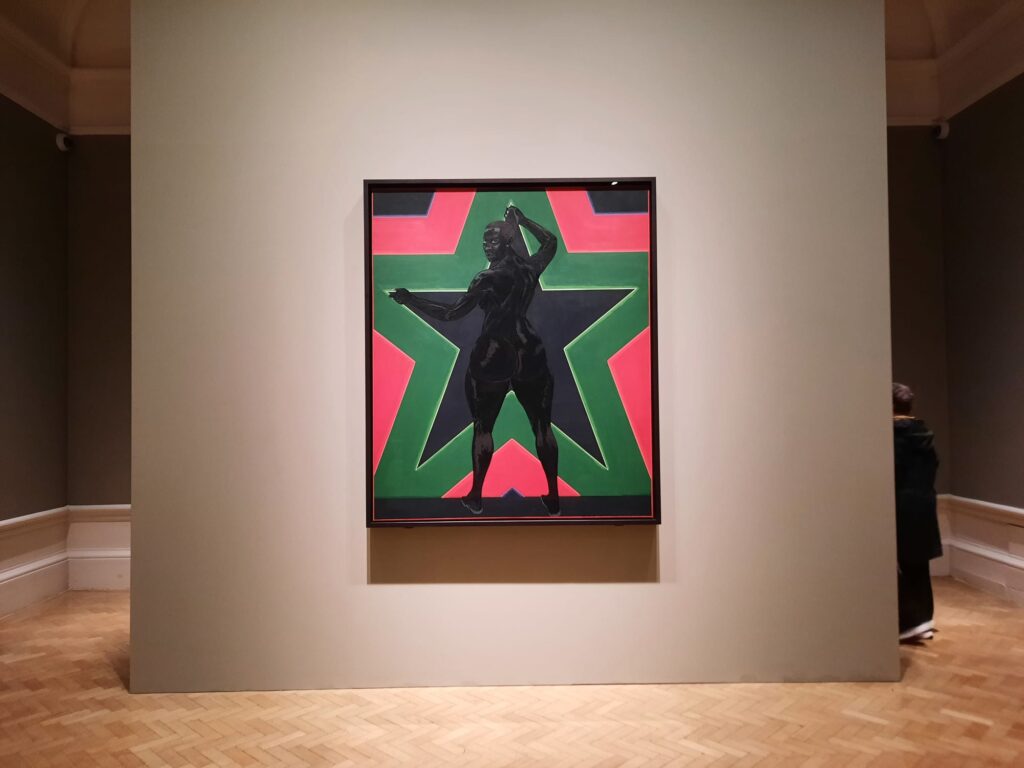

Seeing and Being Seen

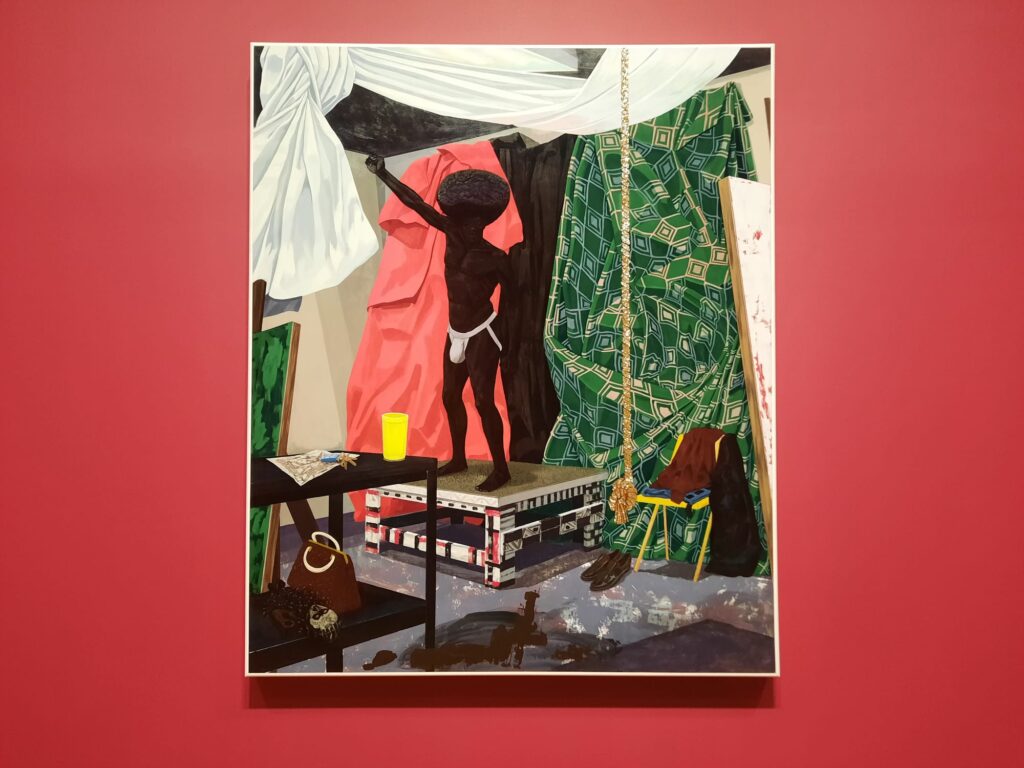

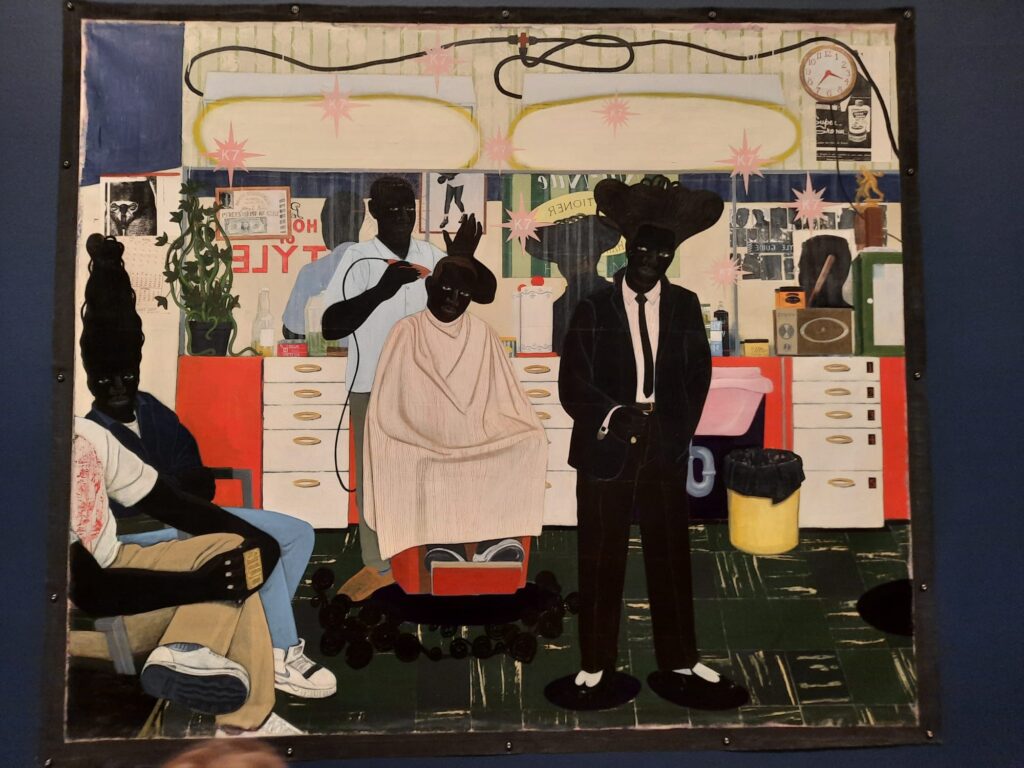

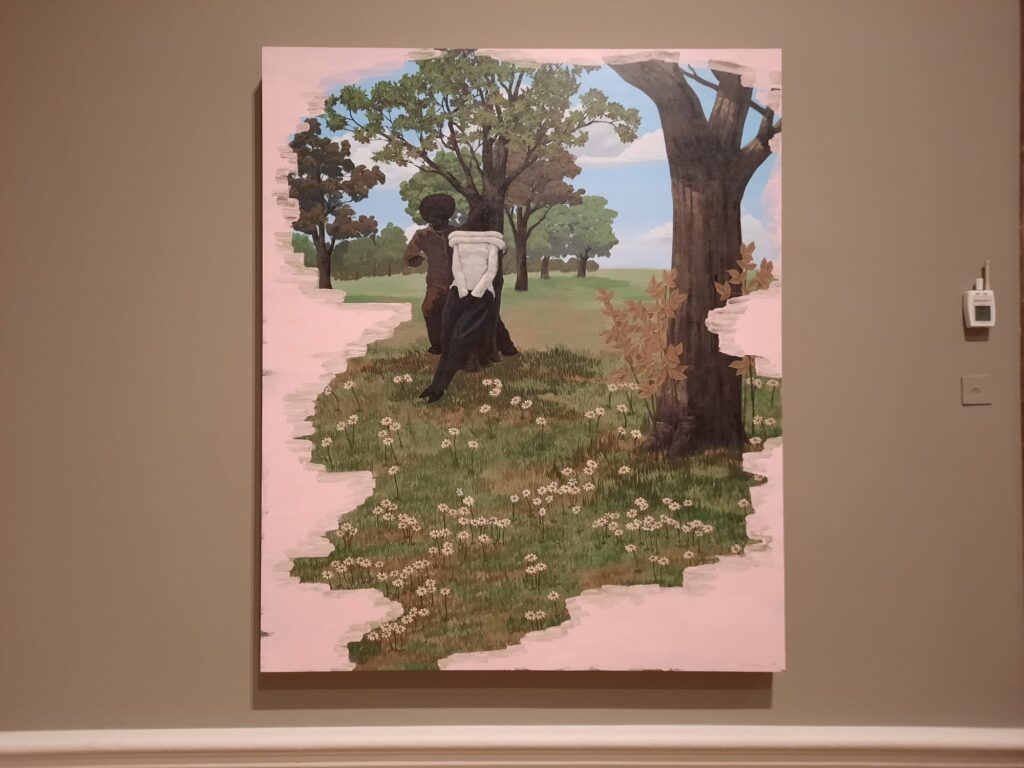

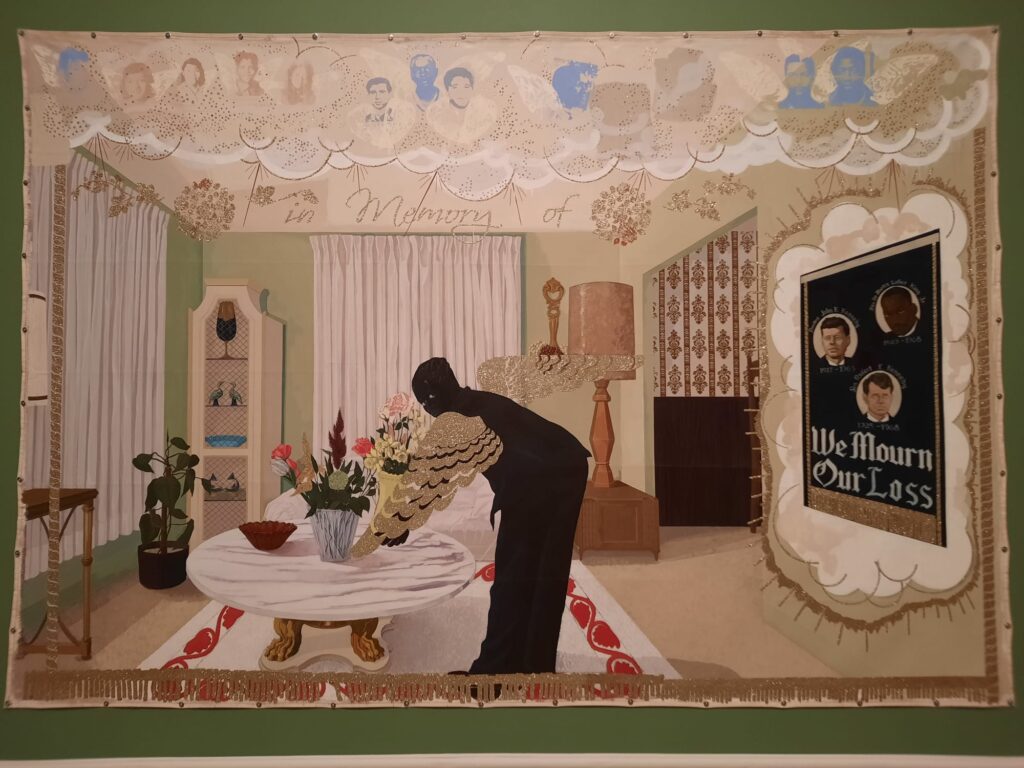

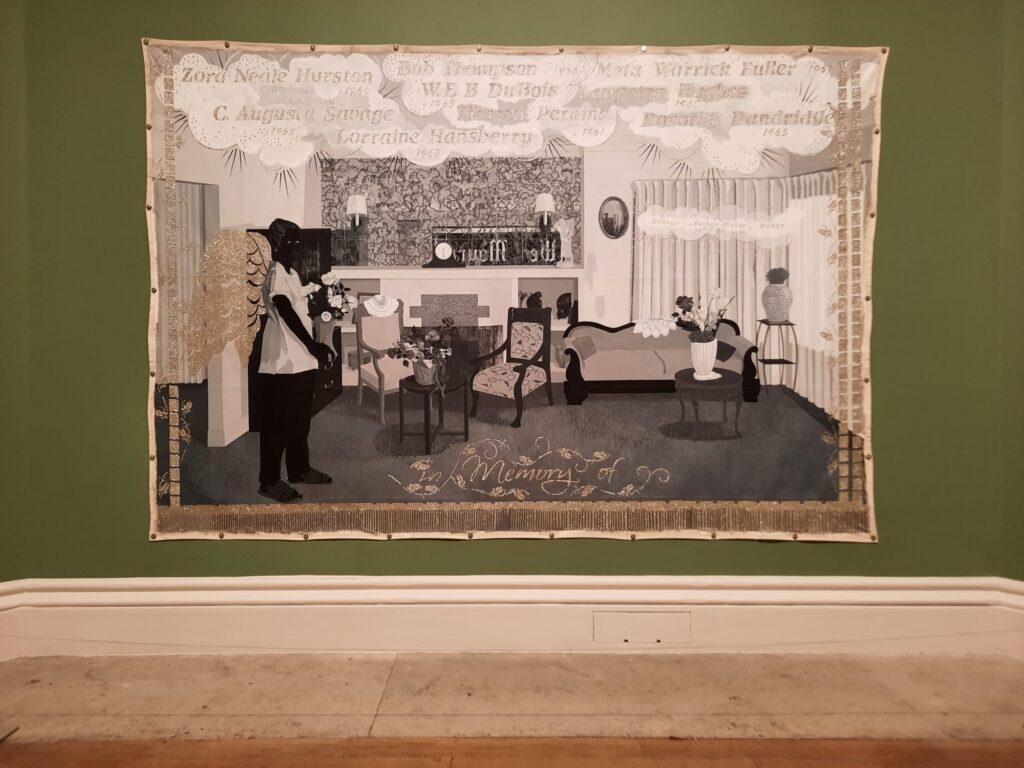

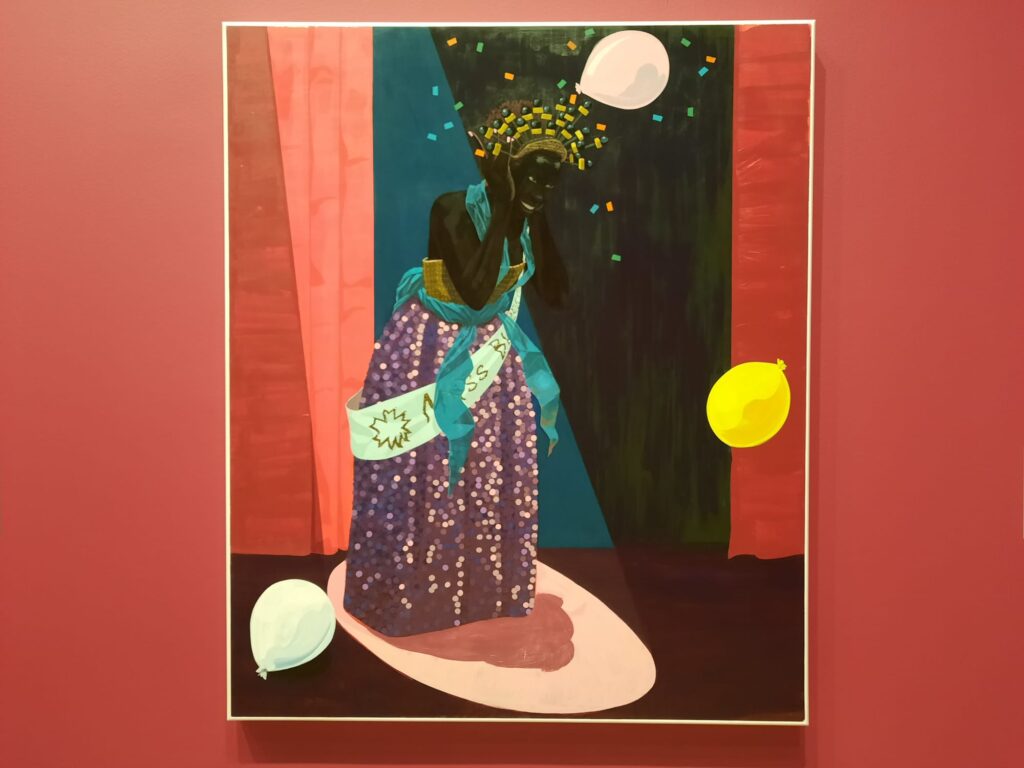

If one half of The Histories is a dialogue with art itself, the other is with history. Who appears within it, and who is made invisible. Marshall’s figures have a real presence. They are rendered in rich, black pigments, not in the browns or warmer tones that might be more “realistic.” It’s a deliberate choice, and one he’s made throughout his career. The effect is striking and political: the figures refuse to blend or soften into their surroundings. It reminds me of the concept of political Blackness that’s come up a few times on the blog: the idea of reflecting society’s own categories back at it. It’s as if Marshall is saying to the artistic establishment (or to society): If this is how you define me, then here is how I define myself within that frame.

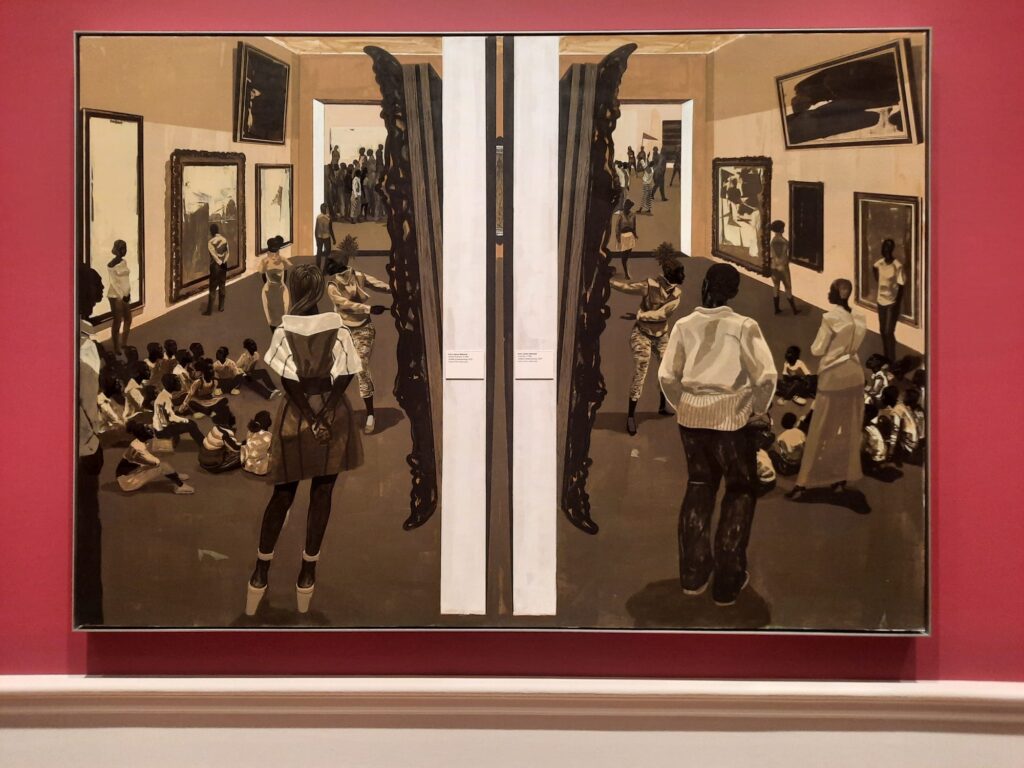

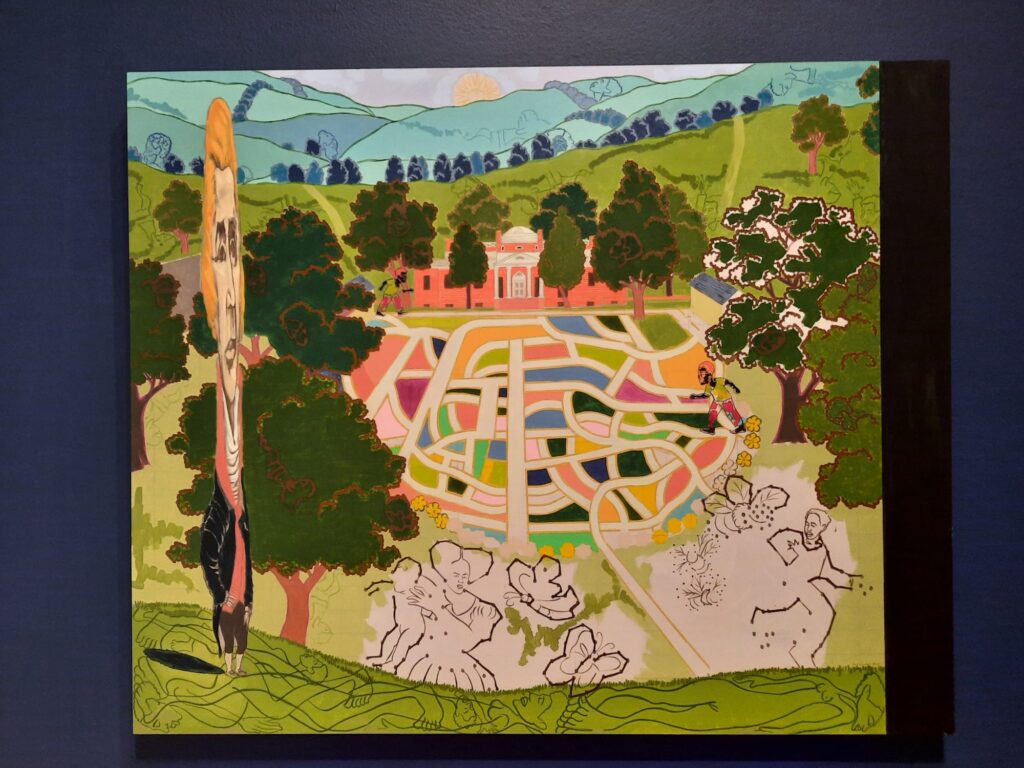

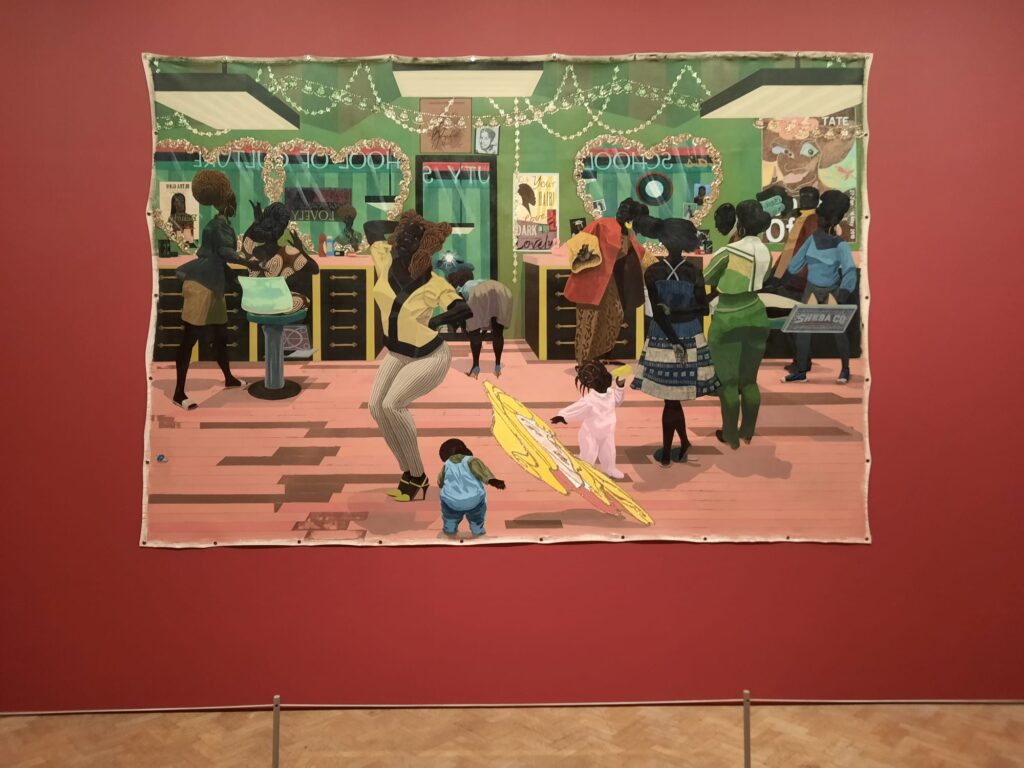

That conversation extends to history itself. Across the exhibition, Marshall revisits familiar symbols and scenes. There are representations of presidential estates built on enslaved labour, portraits of figures such as Scipio Moorhead and Phillis Wheatley, and nods to twentieth-century icons like JFK and Martin Luther King. There are also barbershops, housing estates, libraries, and living rooms. In each case he’s reworking the visual record, showing who was written into history, and who was written out, distorting familiar modes of representation and introducing others. The result is a kind of counter-archive, one that questions how images construct authority and memory.

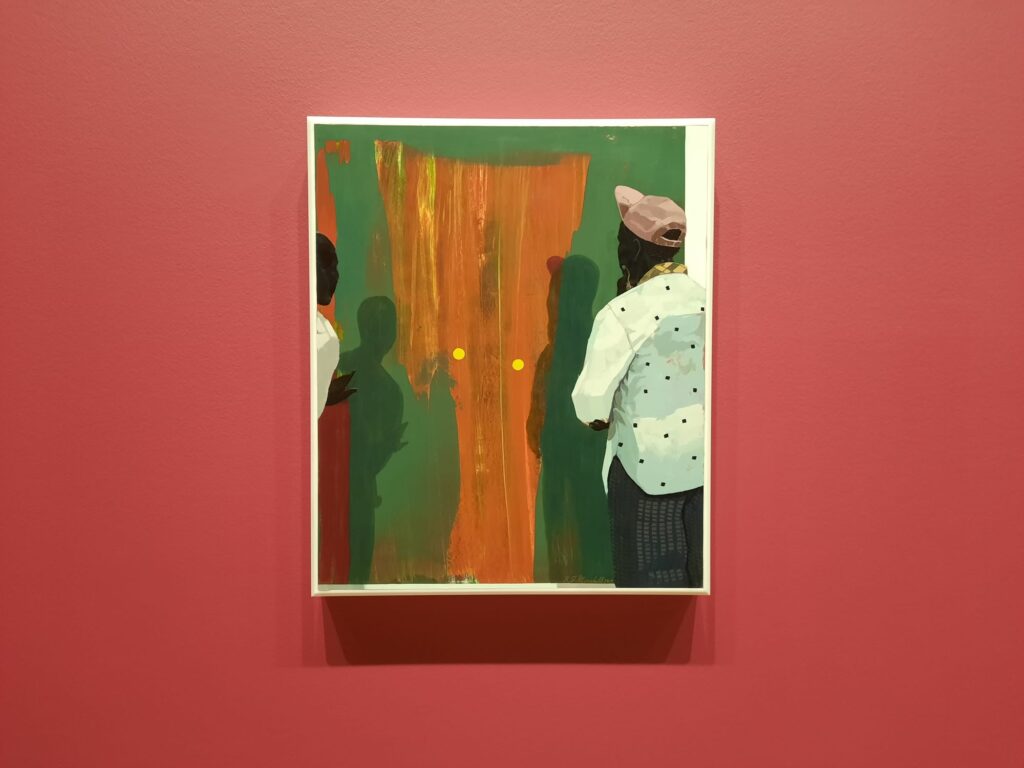

Many of the figures look directly out from the canvas. The gaze is steady, direct, and unembarrassed. There’s confidence in that, but also a kind of levelling: if we’re looking at them, they’re looking back at us. It’s a reminder that representation isn’t a one-way act. Marshall’s figures take up space, they return the gaze, they demand to be met as equals. They also make us conscious not just of history, but of our participation in it.

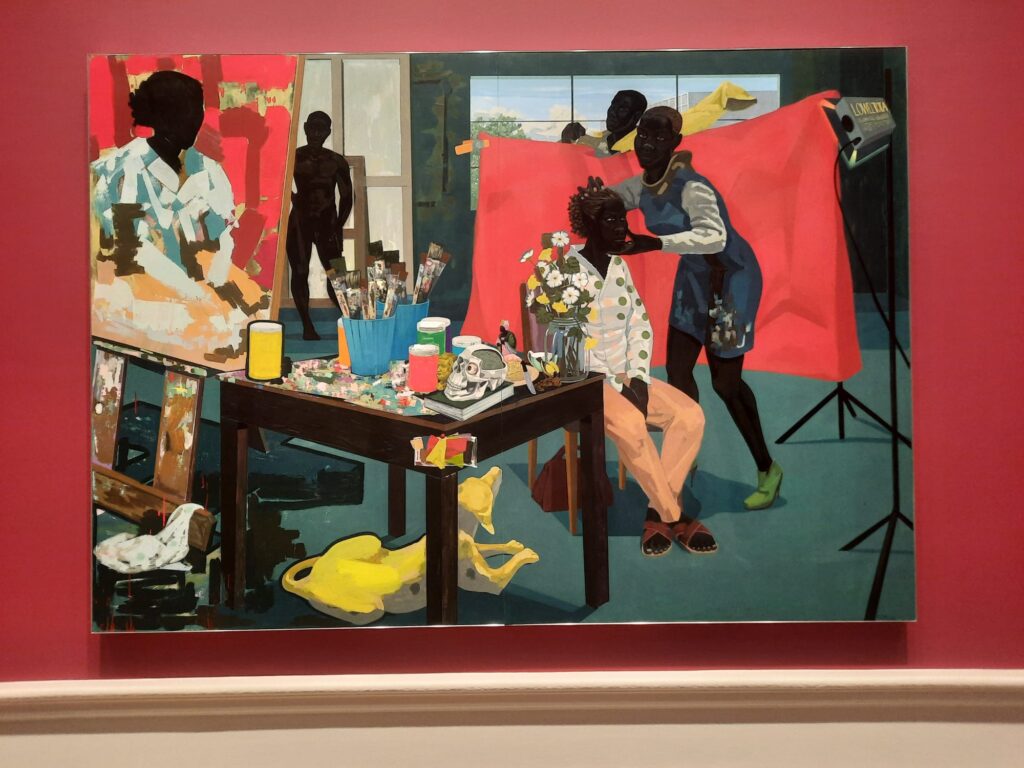

In Dialogue With Art History

Marshall’s work is full of references and echoes of the Western art canon, always with a purpose. He positions Black figures within visual lineages that have historically excluded them, claiming space while also reframing it. Some references are obvious: a reclining figure recalls Manet’s Olympia, for instance. Others take more art historical knowledge and a keen eye: a composition from Winslow Homer, perhaps, or a play on perspective à la Holbein. In other works, the effect of dense black paint interacting with light brings to mind Pierre Soulages, though here the pigment speaks to presence and authority rather than abstraction for its own sake. Each art historical reference is a moment both of continuity and disruption.

What makes the exhibition compelling is how these art-historical threads intersect with everyday life. Those everyday spaces appear alongside figures that echo canonical works. The collision of the familiar and the formal draws attention to exclusions from the canon, while reinforcing the legitimacy of Black presence in these artistic forms. Marshall shows that Black life is not separate from history or art. It can occupy the same frames, command the same attention, and carry the same weight.

Through these juxtapositions, the exhibition also makes a broader point about artistic space itself. By weaving his own vision through references to the canon, Marshall expands what viewers understand as part of the history of art. Rather than simply inserting Black figures into existing frameworks he transforms them, insisting that both the figures and their experiences are central to how we think about art’s past, and how we consider its future.

A Forward-Looking Moment

It was in the final room of the exhibition that I found my favourite work. The paintings here are a bit smaller than many of the earlier pieces, and I liked this more intimate scale. Keeping the Culture (2011 – first image above) shows an Afrofuturist scene of a family on their spaceship. It’s beautiful, hopeful, and full of possibility. After moving through all the layers of social and artistic history that Marshall interrogates, this felt like a gentle reminder of why those themes are important: they’re like a manifesto of survival, imagination, and new futures.

It also shows just how ambitious Marshall is. One canvas might examine the structures of oppression, the next celebrates creativity, agency, or domestic life. That balance of critique and affirmation, reflection and projection, is what gives the exhibition its emotional weight. The histories Marshall presents aren’t solely about the past; they’re about the ongoing negotiation of identity, visibility, and belonging, and about the present and the future as well.

The Royal Academy’s decision to stage this exhibition and others like Entangled Pasts (which included Marshall’s portrait of Scipio Moorhead) adds another layer. It situates his work within a wider effort to challenge the canon and make space for stories that have been overlooked or marginalised. For visitors, it’s a reminder both of what’s been erased and of what can be reclaimed, whether that’s in art, in history, or in everyday life.

The Histories leaves you aware that these conversations are ongoing. It asks you to look, to reflect, and to think about what you have yet to understand. And in doing so, it makes a strong case for why Kerry James Marshall remains one of the most important artists working today.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories on until 18 January 2026.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.