M. V. Frunze House Museum (М. В. Фрунзенин Үй-музейи), Bishkek

A childhood home encased in concrete, a museum preserved in amber: the M. V. Frunze House Museum is a great final stop in Bishkek.

One Final Museum in Bishkek

We’ve had a pretty good look around Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan’s capital, at this point. I wrote a ’48 Hours’ guide first, which covered Osh Bazaar, day trips, parks, food, and more.

Then we started looking at individual museums, beginning with the Museum of the National Academy of Arts T. Sadykova. This was a very unique visitor experience, but taught me a lot about the sculptures of Tinibek Sadykov, and also the potential for AI to break down language barriers in real time. Next was the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic. Here we started discussing a topic we’re going to talk about again today: the fetishisation of the Soviet period and whether a museum is better staying as a time capsule or evolving. My most recent post was about the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva, a collection of mostly Socialist Realist art (with some other periods mixed in as well as applied art) in a fantastic Soviet Brutalist building.

And now we’re at the final museum. Don’t worry, we’re not leaving Kyrgyzstan just yet. My next post will cover trekking in the Tien Shan Mountains from a cultural and historical perspective. Then we have a little piece on the town of Tamga. But as far as Bishkek goes, this is it. The last post. And it’s a good one. At least as far as those who enjoy the nostalgia of Soviet relics go.

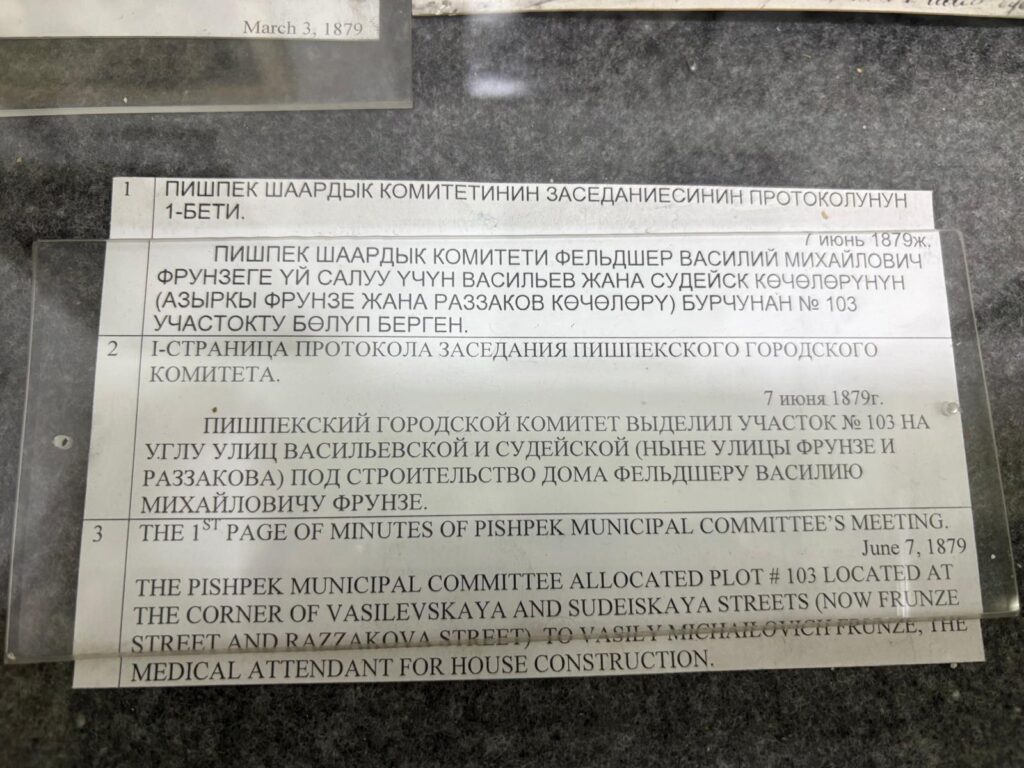

Frankly, that’s what I was hoping for when I visited. I knew from the description that the museum was dedicated to Mikhail Frunze, for whom Bishkek was named for several decades (from Pishpek during the Russian Empire period, the town/city became Frunze, and then Bishkek post-independence). And I also knew that it contained Frunze’s childhood home within the museum. Although nobody seems to really believe that it’s the real deal. All in all, it sounded like such a unique experience I wouldn’t want to miss it.

A Little Background: M. V. Frunze

I almost can’t wait to tell you about the visitor experience, but we must start at the beginning. Which in this case, means understanding who this museum is all about.

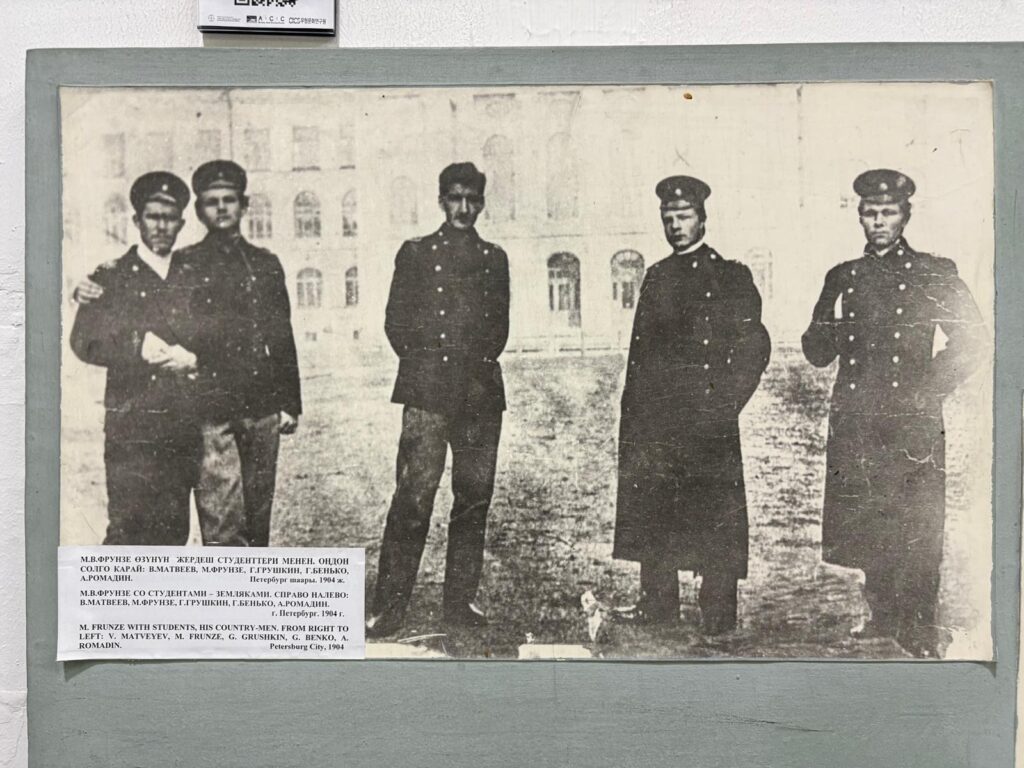

Mikhail Vasilyevich Frunze was born in 1885 in Pishpek which, as we’ve established, is now the city of Bishkek. At the time it was part of Russian Turkestan. Frunze, attending the Saint Petersburg Polytechnical University, joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. After that party split, he sided with the Bolshevik Party. During the failed 1905 Russian Revolution he led striking textile workers, resulting in a death sentence that was later commuted to hard labour in Siberia. After ten years of that Frunze escaped, just in time to be a key figure in the successful Russian Revolution. He variously led the Minsk civilian militia, was president of the Byelorussian Soviet, led an armed force of workers in the struggle for Moscow, led troops who defeated the White Army, took the Crimea, was an ambassador, a member of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party. Basically, what didn’t he do?

Live a long time, is the answer to that. Frunze suffered from a serious stomach ulcer, and was dubious about undergoing surgery for it. In 1925, when he did finally undergo surgery, it killed him. Well, whether it was the surgery, or Stalin using the surgery as cover to get Frunze out of the way, seems to be up for debate. He was certainly talked about as a potential successor to Lenin.

Anyway, as Lenin also found, dying during the 1920s was a good way to secure a positive legacy. An extreme but irrevocable way to avoid getting bogged down in the realities of the administration of the USSR. As early as 1926, Pishpek was renamed Frunze in his honour (and the airport code only changed from FRU to BSZ in August 2025 while I was there). As well as this museum and a street named for Frunze (many more likewise across the former Soviet Union), there’s an equestrian statue of the man himself near Bishkek’s train station.

The M. V. Frunze House Museum

I very much enjoyed my visit to the M. V. Frunze House Museum from the start. While a museum centred on Frunze’s childhood home goes back to December 1925 (quick work), this building dates to 1967. Like the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts, it’s a nice example of Soviet Brutalism. Lots of concrete in a monolithic form, utilitarian yet dramatic. The museum has concrete murals wrapped around all four sides, the work of Alexander Voronin and Alexei Kamensky.

Inside the staff were very welcoming, despite a language barrier. Given I could tell it was a bit of a time capsule, it surprised me that the museum was cashless. Don’t judge a book by the hammer and sickle on its cover, I guess. The same friendly staff then directed me upstairs to begin my visit.

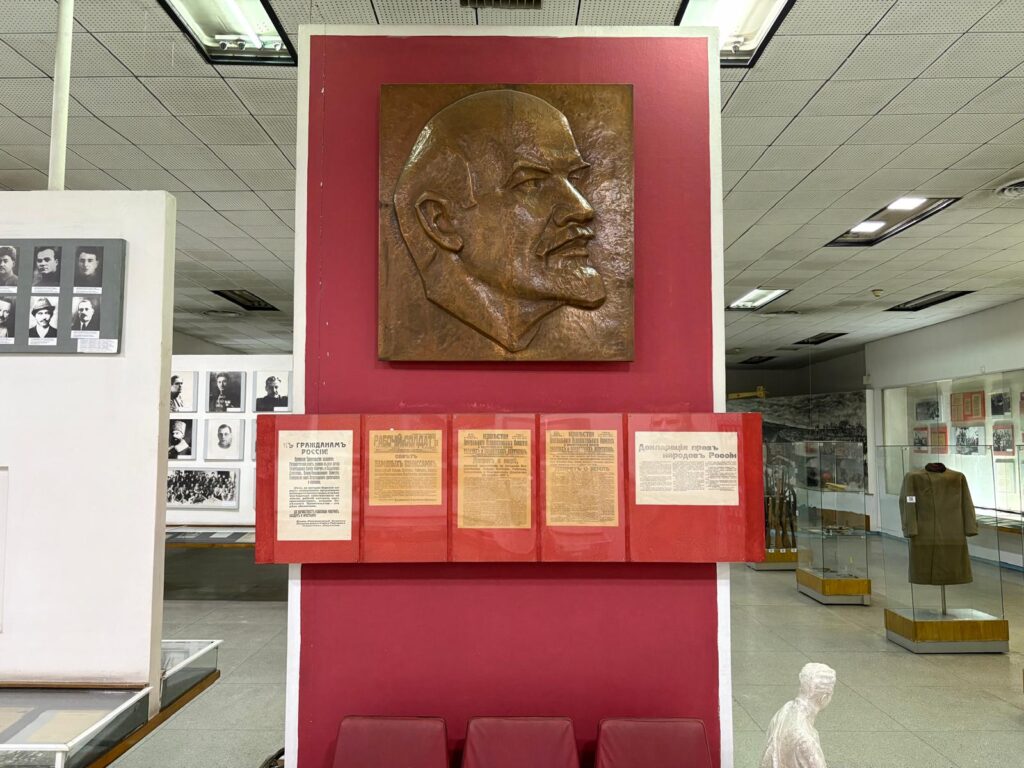

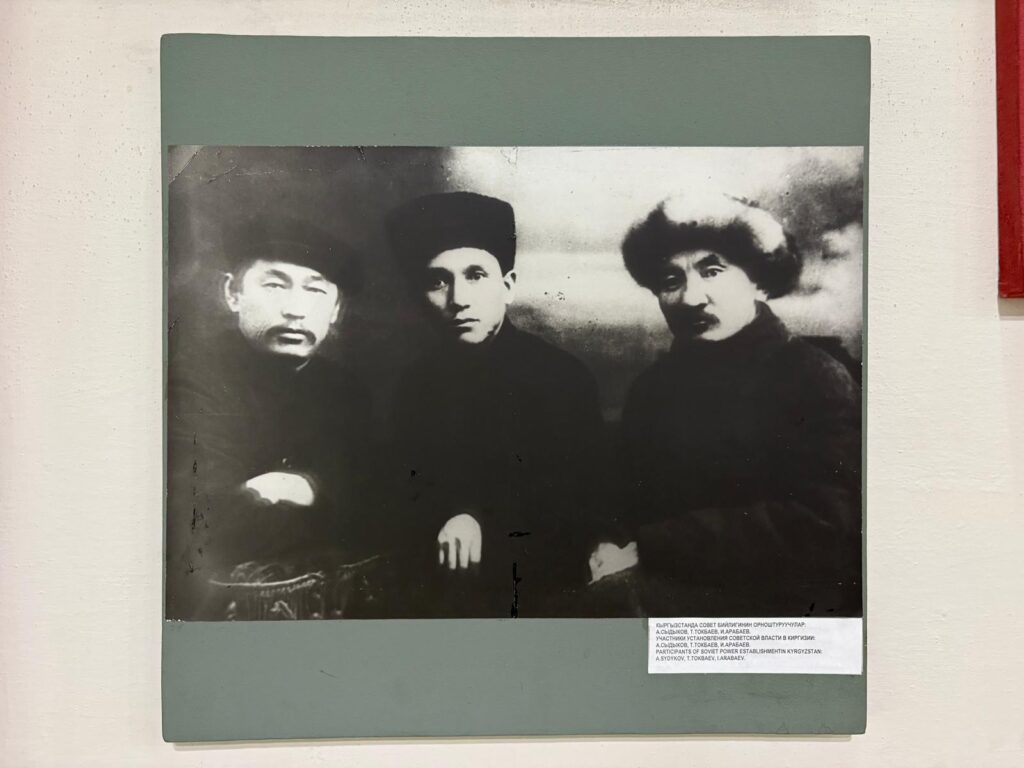

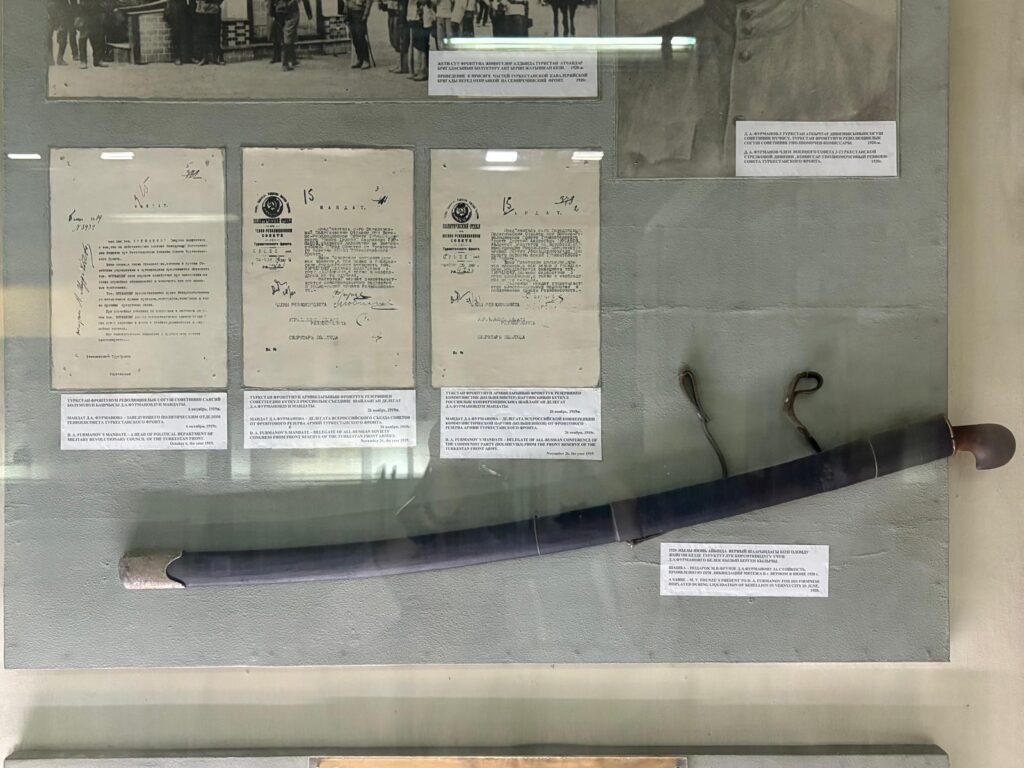

Walking through into the first museum space, a relief portrait of Lenin greeted me. An excellent start. I then proceeded to walk around the displays, which consist of a lot of documentary materials (often copies of the originals), a few objects, and the odd imaginative display, recounting Frunze’s life and deeds in great detail. While a lot of the materials are in Russian, most labels are in Kyrgyz, Russian and English. So you at least get an idea of what’s going on. Eventually, I got to the end of the top floor, and made my way downstairs. The next floor down was closed: it seems like maybe it’s a temporary exhibition space as I know the museum holds these from time to time.

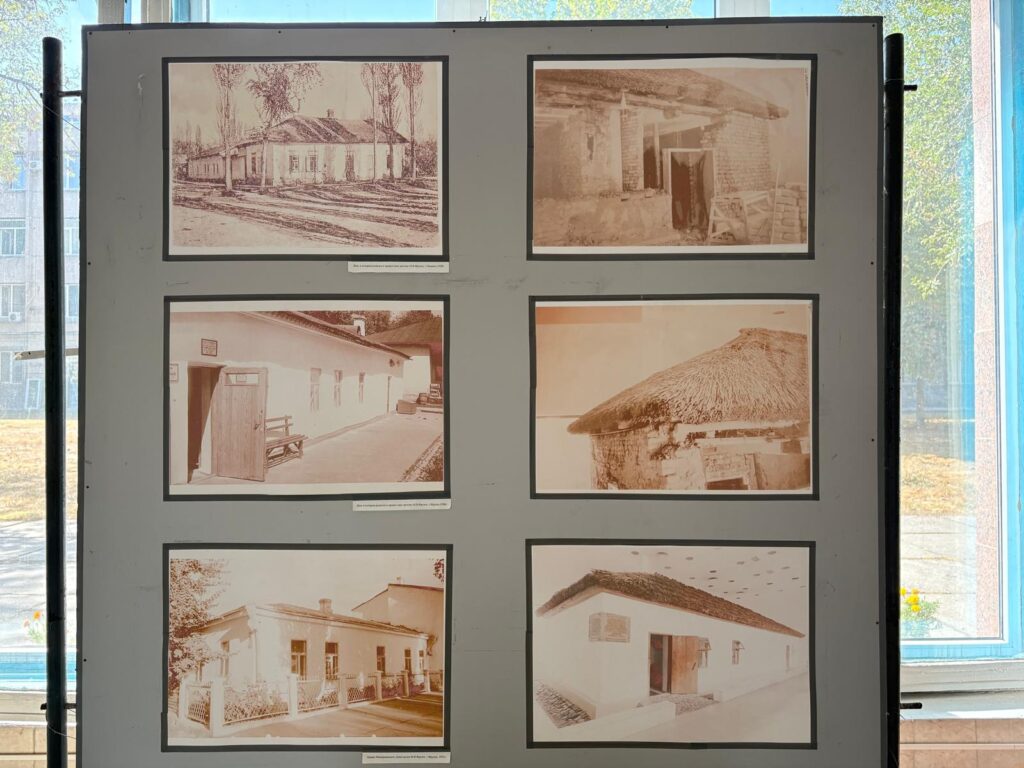

And then on the ground floor, I found the main event. Frunze’s childhood home. Or a home very much like his childhood home? It’s a little unclear and depends who you believe. I mean 1925 is not so far away from 1889 when Frunze’s father reportedly built said home – you’d think his family would know and say whether it was that one or not. On the other hand, the Soviets did like a nice bit of patriotic hero worship, and that’s a lot easier with a focal point. At this stage, who can say?

Either way, the house which is reportedly Frunze’s childhood home is neat and well-maintained, with furniture and objects illustrating its use (some of the collection was donated by Frunze’s family so perhaps these are authentic). Not speaking Kyrgyz or Russian, I didn’t benefit from the wisdom of the museum attendant who was showing a local couple around, but saw my fill and then left.

Final Thoughts on the M. V. Frunze House Museum

When I visited the National History Museum in Bishkek, I talked about how easy it is to fetishise the Soviet period; to want to be able to experience something of a different time and a different system without enduring any of its complications and hardships. A sort of nostalgic Socialist tourism. I acknowledged that this was a bit problematic: if the National History Museum has been renovated into ‘international museum’ style and tells a more contemporary story, this ultimately serves its audience and community better than staying preserved as a time capsule.

This museum is a little different though. It’s primary purpose no longer really exists: this is no longer the museum about the guy the city is named for, but the museum about the guy the city used to be named for. And independent Kyrgyzstan has understandably turned more towards ethic Kyrgyz heroes, rather than Kyrgyz-born Russians.

And so, the M. V. Frunze Museum was the perfect place to scratch my Soviet nostalgia itch. If we exclude the cashless payment part, I doubt the museum has changed very much at all since the Soviet period. Maybe a little in how it presents Frunze’s story, but I think any resident of Frunze would easily recognise it in its current form. Really, though, this desire to experience the past isn’t unique, or even unique to former Soviet museums: many visitors to the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands, are going for its time capsule feel.

That, for me, was the beauty of visiting this museum. A museum preserved in amber. A product of its time, and interesting for this fact rather than the content (which is pretty dry). If you have any interest in 20th century history or architecture, or museum curiosities, set aside some time during your trip to Bishkek to visit.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.