National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic (Кыргыз Республикасынын Улуттук тарых музейи), Bishkek

The National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic offers a modern, well-presented overview of Kyrgyz culture and history, balancing nomadic traditions, Soviet-era politics, and contemporary identity, even if some silences remain in its narrative.

Let’s Start by Talking About the Fetishisation of the Soviet Period

When it comes to crafting each post on the Salterton Arts Review, I have to pick a starting point. Perhaps an observation, or an anecdote. Perhaps a comparison to link it to something else I’ve seen recently. Regular readers will be aware that this is part of a series exploring my recent visit to Kyrgyzstan. But I want to start today by talking about the fetishisation of the Soviet period, and how it applied to my visit to the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic.

I want to be really clear before we go further that I don’t mean sexual fetishisation. I’m coming at this more from the context of my training in museology. What I actually mean is something similar to Orientalism per Edward Said: “a biased framework through which the West constructs the East as exotic, irrational, and inferior”.

Applied to the countries of the former Soviet Union or Eastern Bloc, I’m talking about a behaviour, in which I’m not alone, of seeking out things that are different and distinctive because they encapsulate (for me) this period. And viewing them with nostalgia through an undoubtedly biased lens. A statue of Lenin? I’ll for sure be going to see that! Hammer and sickle designs on the opera house? Yes, I’ll go out of my way to see those! Have I reduced a very complex period of history/experience for different ethnic and religious groups, into a simple nostalgic concept? Yes, I’m sure I have!

How does this apply to the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic? Well, it’s about what it is now and what it used to be. After an extensive renovation programme, the museum today is modern. It’s actually very much like any other sizeable history museum around. But… I can’t help seeing images like this one and feeling a twinge of regret that I’m seeing a museum like any other, and all the Soviet-era murals, statues and displays are gone. So far I haven’t gone beyond identifying this tendency: more thought required on what, if anything, to do about it.

And despite the problematic elements I’ve raised, there are definitely museums in Bishkek you can visit if you wish you were in Frunze instead. See my next couple of posts, for instance.

Right, Now Let’s Get To It

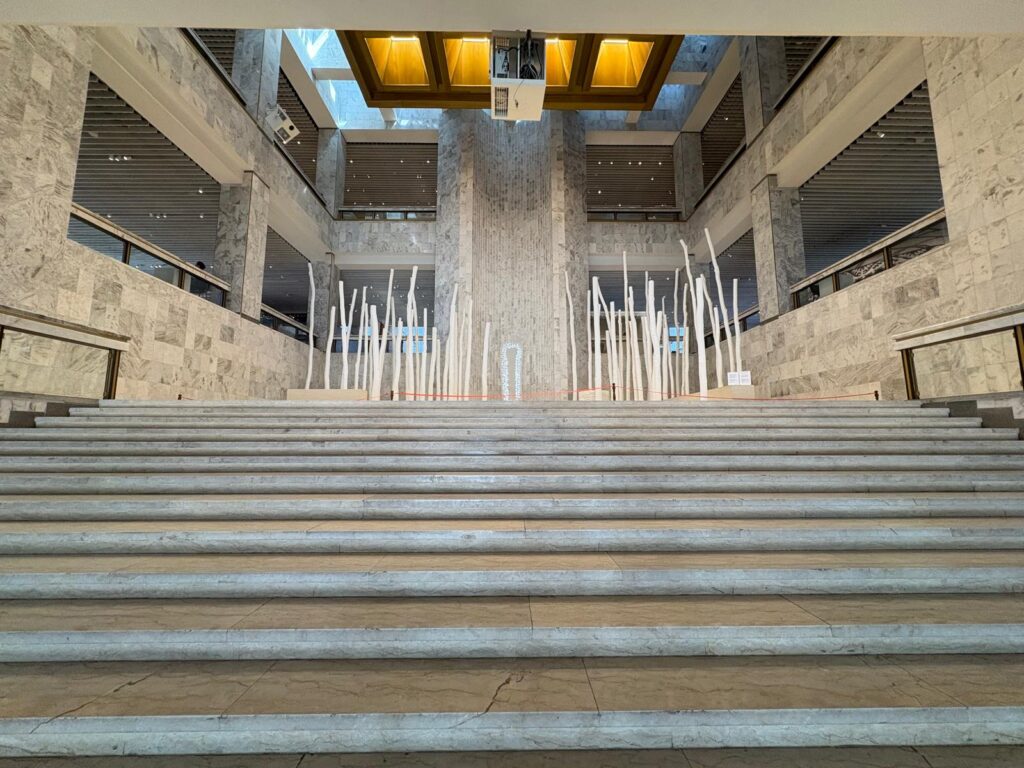

Enough scene setting. It’s time to talk about the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic. And, once I set aside my disappointment that the museum hadn’t kept itself a time capsule for my benefit, my first impressions were good. This is not the first building to house the National History Museum. The collection goes back to 1925, opening to the public in 1927. In the 1960s it moved to a 1928 building, and moved to this current one in 1984. It’s in a prime location in Ala-Too Square, and was designed to have a distinctive appearance.

The museum had various names over that period, too. From the Central Museum of Kyrgyzstan, it became the Museum of Local Customs in 1933. From 1943 it was the Museum of National Culture. Then from 1954 the State Historical Museum. There’s probably another interesting angle on the museum there. The tension between a outsider’s ethnographic view on Kyrgyz culture, and acknowledging Kyrgyz culture as the predominant one within the Kyrgyz SSR and later republic.

The renovation project began in 2016, funded partly by the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency. Another way, along with funding Bishkek’s new Central Mosque, of maintaining a role in this Turkic part of the world. The renovations stripped away a lot of the past. The murals, statues and Soviet displays are gone. In their place are clean lines and smooth stone, metal and glass. It wasn’t without difficulties as a project, though. Initially planned to take less than a year, the museum only reopened in the end in 2021. And during that time, several government officials, including a former Prime Minister, were charged with misappropriating funds.

A lot of space inside is given over to museum logistics. A big ticket desk, a small shop and a tiny cafe as you enter. Downstairs are toilets and a mandatory bag check. Mandatory camera check too, in my case, although photos with a phone seem to be fine. Done with all that, I headed back upstairs and started my visit of the museum proper.

From Early History to the 1920s

The first floor of the National History Museum promises, at first glance, a sweeping overview of Kyrgyz history from prehistory up to the 1920s. This is the classic “national story told chronologically” model. But interestingly it doesn’t start with archaeology. Even though I know from visiting Burana Tower that Kyrgyzstan has plenty of petroglyphs if nothing else. Instead it begins with information about Kyrgyz clans and their migrations, with a few accompanying objects. It then moves into objects illustrating nomadic culture, starting with a yurt and then dividing by material (textiles, woodwork, metalwork).

The presentation is clean and modern, very much in line with other recently renovated museums I’ve seen. But what kept catching my attention was the dating of the objects themselves. Many of the pieces on display are not ancient survivals but 20th-century examples of longer traditions. In one sense that’s inevitable: a museum founded in the 1920s could only really collect what was available then. But as a museologist it left me slightly uneasy, because the objects are displayed as if they represent an unbroken chain of “authentic” Kyrgyz culture stretching back centuries.

The reality, of course, must have been more complicated. By the time of the museum’s (and collection’s) founding, Kyrgyzstan had already experienced profound shifts. Namely contact with neighbouring cultures, integration into the Russian Empire, and, by the mid/late 1920s, the policies of the Soviet Union. Access to new materials, the encouragement (or imposition) of more settled lifestyles, and the influence of Russian tastes must have shaped what Kyrgyz objects looked like and how they were made. Yet in the museum these factors are in the background.

One feature I did appreciate was the inclusion of Russian material culture from the 19th century. Particularly the ethnographic presentation, in exactly the same way as Kyrgyz artefacts. Domestic items from Russian settlers have their own display case, as though they too were simply one group contributing to the patchwork of life in the region. This, of course, underplays the Russian Empire’s role in what is now the Kyrgyz Republic. But it also has the unexpected effect of equalising the narrative: Russians were not only the agents of empire here, but also one of the many communities that made up Kyrgyzstan. And are not (any more) the ones casting an ethnological gaze onto others. In a museum that has reckoned with changes in political structure, population and perspectives on history, I found that choice intriguing.

The Soviet Period and After

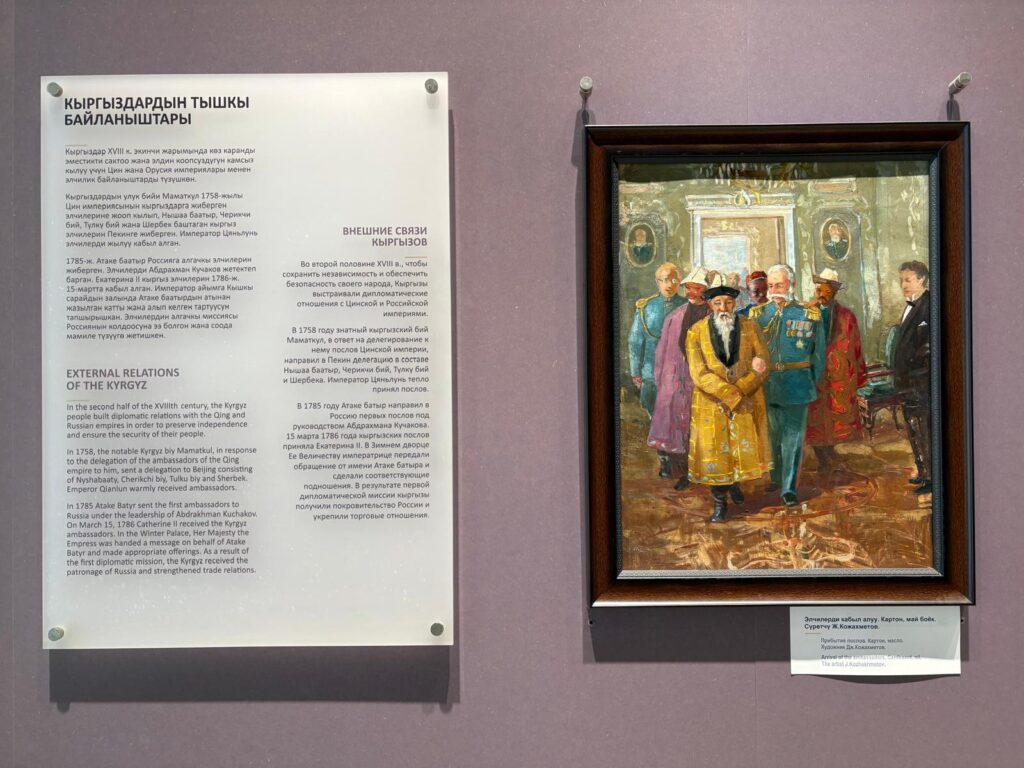

The second floor of the museum makes an immediate break from the ethnographic feel of the ground floor. Here the cases contain paper and images as well as objects. There are official decrees, propaganda posters, political portraits, and photographs of leaders. The narrative, too, shifts from culture to politics. Displays cover the Soviet period in some detail, and the sheer volume of material suggests that much of this was already in the collection. What has changed, presumably since independence and again since renovation, is the way it is framed. Rather than serving as evidence of Soviet progress, the objects now chart the experience of Kyrgyzstan within the Soviet system. Industrialisation, literacy campaigns, political repression. All are presented as significant events happening in this specific place, rather than subsumed into a wider Soviet narrative.

As the chronology progresses towards independence and the present day, politics begins to give way to cultural life once more. One display showcases theatre costumes; others literature, or cinema. The tone is celebratory, and the emphasis is on cultural achievement and national pride. It is interesting that as independence approaches, the museum’s own focus subtly pivots: from life on a political scale to affirming Kyrgyzstan’s cultural identity as something distinct, even when those traditions unfolded within a Soviet framework.

That shift suggests the museum’s role is not simply to preserve the past but also to help determine the nation’s present. If the ground floor felt like a record of “timeless” traditions, the second floor positions Kyrgyzstan as a modern nation-state with its own cultural voice. The balance between inherited Soviet material and newly framed national narrative is tricky, and at times uneven. But it is also revealing. This is a museum negotiating, in real time, how to tell the story of a country that has moved from empire, to Soviet republic, to independent state in little more than a century.

The Visitor Experience

Whatever questions linger about the handling of funds during the long renovation, it’s clear that some of that money went on updating the visitor experience. The display cases, particularly on the first floor, are modern and carefully lit. Objects are well-spaced, mounted cleanly, and lead the displays rather than overwhelming visitors with text. For anyone who did check out the photo of the museum’s Soviet-era interiors, the shift to this sleeker, international style is a striking contrast.

That said, by the time you reach the end of your journey, the energy seems to dip. Displays feel thinner, sometimes petering out in a way that leaves you wondering whether this was due to diminishing funds, the difficulty of contemporary collecting, or perhaps just curatorial fatigue. Collecting the present is notoriously tricky for any museum, but it is particularly noticeable when so much is riding on the ability to tell the story of post-Soviet independence.

As a foreign visitor, I also appreciated the effort to make the museum bilingual. Most labels and wall texts are available in English – enough to make the displays legible and accessible in a way that some Bishkek museums are not. This feels very much like an institution positioning itself for international visitors as well as national pride.

Still, there are gaps. There are occasional displays on women or minority groups, but they come across more as add-ons than organically integrated narratives. And when it comes to politics after independence, the museum treads lightly. Kyrgyzstan has seen multiple uprisings and regime changes in the last three decades. This continuing insistence on democracy is barely acknowledged within the museum. The religious tensions that periodically flare are absent too. It feels like certain histories remain a bit too sensitive, so the story pivots instead towards safer ground – culture, theatre, literature.

Reflections and Final Thoughts

Despite my earlier musings about what was “lost” in the renovation (the Soviet murals, the nostalgic thrill of stepping into a different museological era) the National History Museum is still the one I would recommend to most visitors to Bishkek. It offers a broad, accessible introduction to Kyrgyz culture and history which, for a traveller with limited time, is invaluable. The presentation of nomadic traditions is clear and visually engaging, especially the sections on textile work and design, which really show off the richness of Kyrgyz applied arts. And for those who want to understand the Soviet period, the museum’s collections give a well-rounded sense of how that history unfolded here, even if the narrative thins out afterwards.

For me, the visit was also a small corrective to my own biases. I went in half-hoping for a Soviet-era museum frozen in amber, a place that would confirm my fascination with the visual and ideological strangeness of the period. What I found instead was a museum that has tried, with mixed but fairly impressive results, to modernise and reframe Kyrgyz history for today. If other museums in Bishkek still carry that Soviet atmosphere, it’s likely less a matter of choice than of resources. And perhaps, in the end, those old museums don’t serve the purpose they really should: they don’t explain Kyrgyzstan today.

This one, in its international, glass-and-stone way, does make the attempt. It cannot be exhaustive, nor can it escape certain political and curatorial limits. But it shows how a national museum can work with what it has, and in doing so gives visitors a clearer sense of Kyrgyzstan’s complex past and its evolving identity.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.