Design and Disability – V&A, London

The V&A’s Design and Disability is an ambitious and necessary exhibition that places disabled creativity and design at the centre of museum culture, exploring how accessibility, innovation and identity intersect

Design and Disability

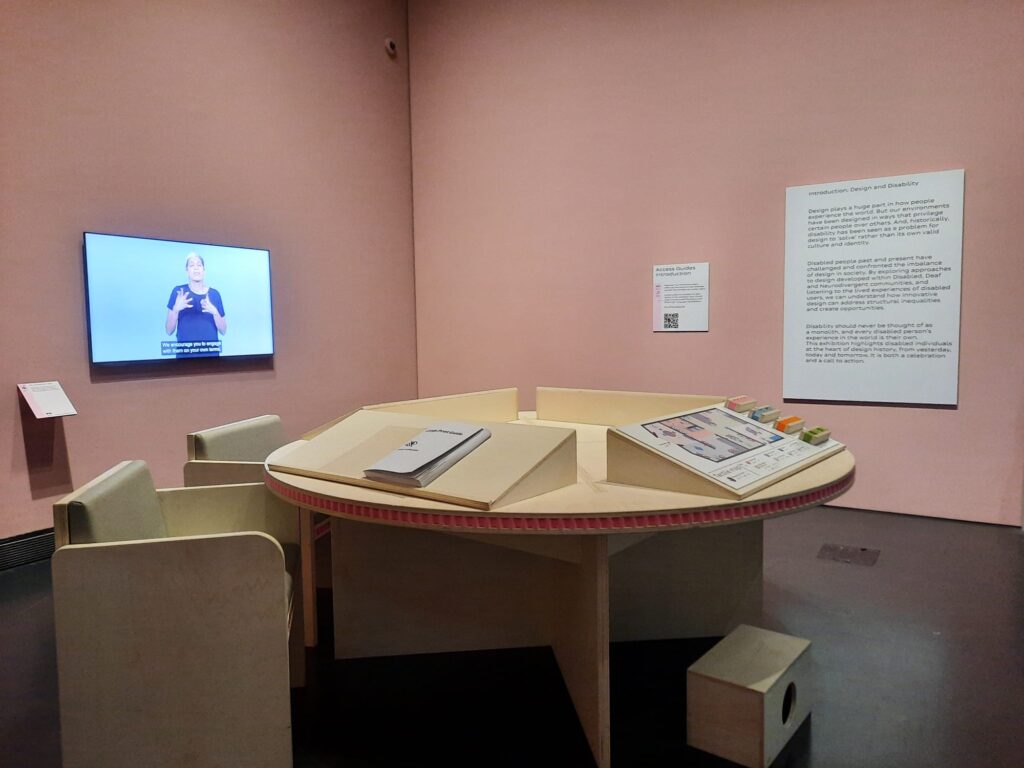

I recently had the opportunity to visit the V&A’s Design and Disability exhibition. It is an interesting one, marking a shift in how major museums engage with disability. Curated by Natalie Kane, who identifies as disabled, the show states clearly that disabled, D/deaf and neurodivergent makers are central actors. It is structured around three sections: Visibility, Tools and Living. These sections trace design from identity through adaptation into environment and society. The significance of the exhibition lies in positioning disability not as a deficit but as culture, expertise and innovation. The press release makes this ambition explicit, calling it a “celebration of Disabled-led design and a call for action”.

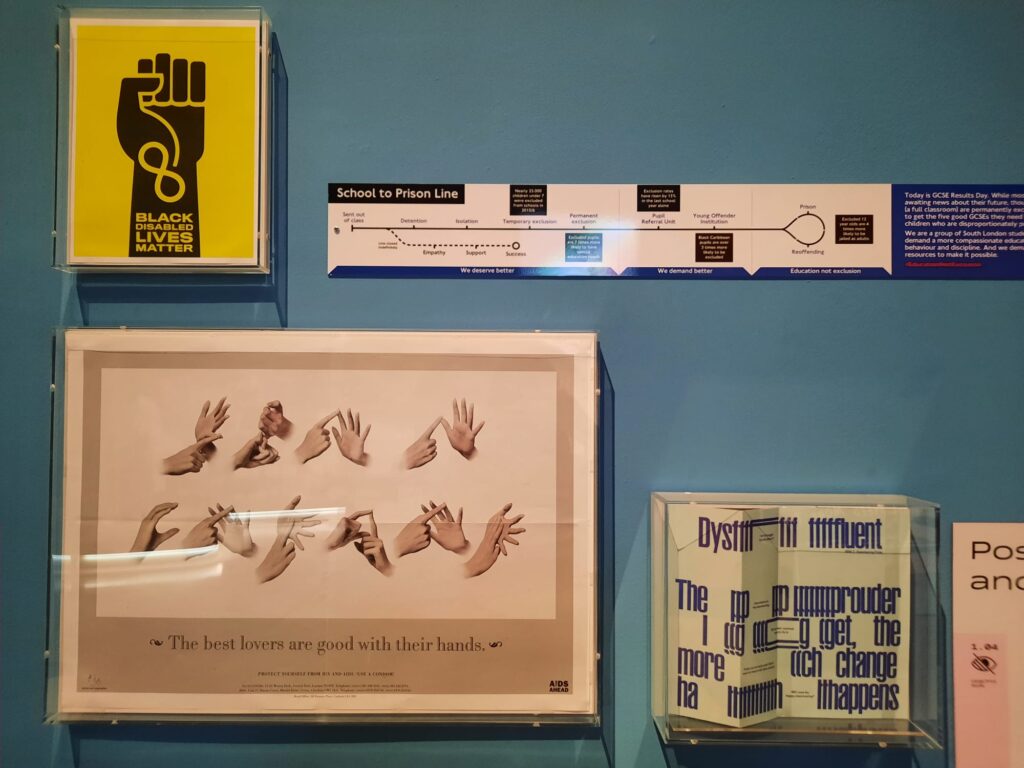

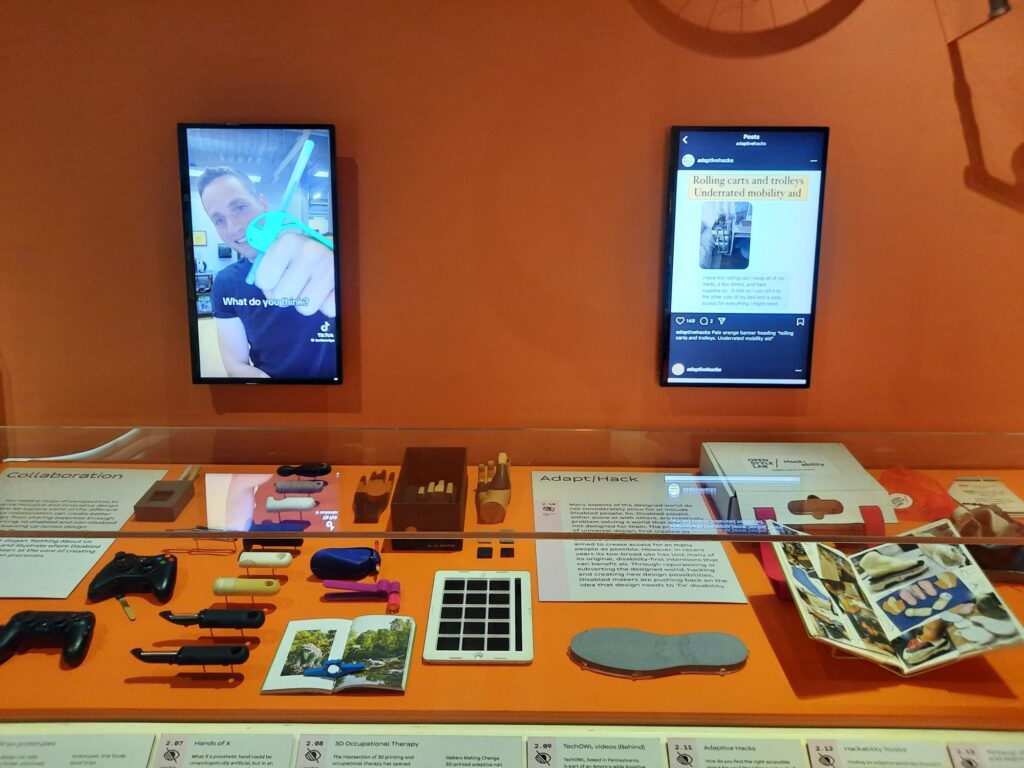

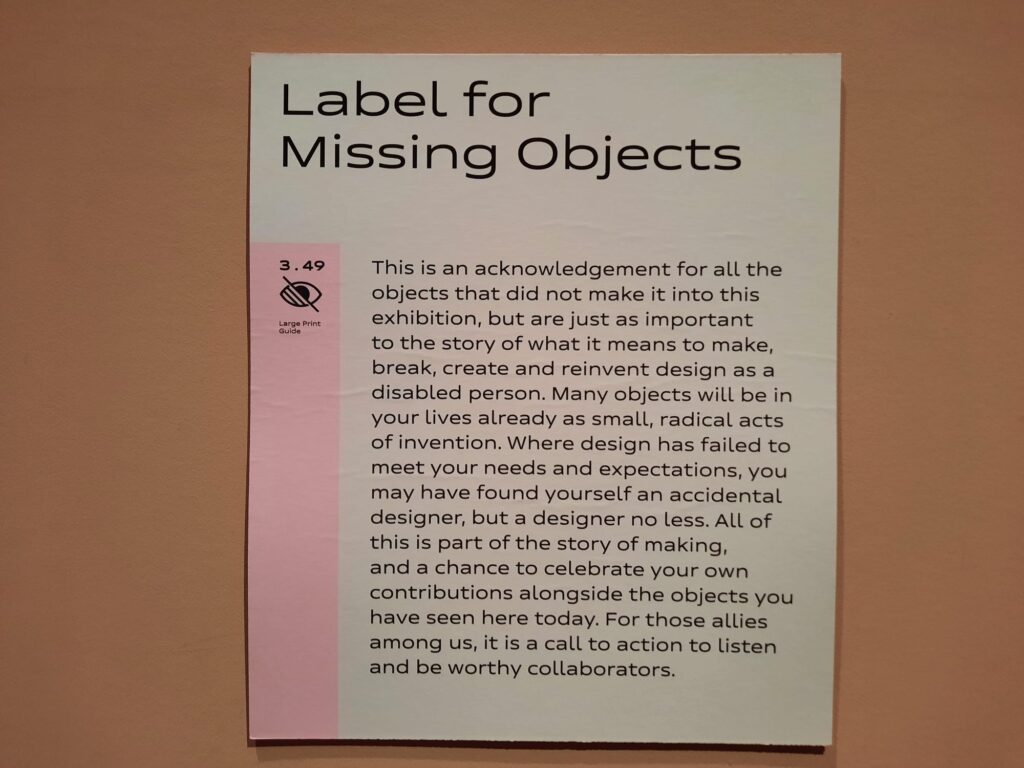

From a political or academic perspective, the exhibition is at the intersection of design history and disability studies, inviting us to question who designs, for whom, and why. It brings to mind the slogan adopted by the disability-rights movement: “Nothing about us without us”. The V&A thus offers itself up as more than a repository of objects. It becomes a site of contested meaning, interrogating access, identity and cultural production. In showing both typical museum objects (fashion, architecture, assistive devices) and grassroots DIY artefacts, the V&A acknowledges both top-down and bottom-up design processes.

That the exhibition is taking place in a major London museum would seem to signal a growing mainstream recognition of disability design. Yet it also poses questions: how fully can such institutions rethink embedded ableism? How much can they shift their own structures rather than adding a “disability” show? The exhibition’s intentions are certainly valid. Let’s now see how they play out in practice.

Where is the Exhibition Successful?

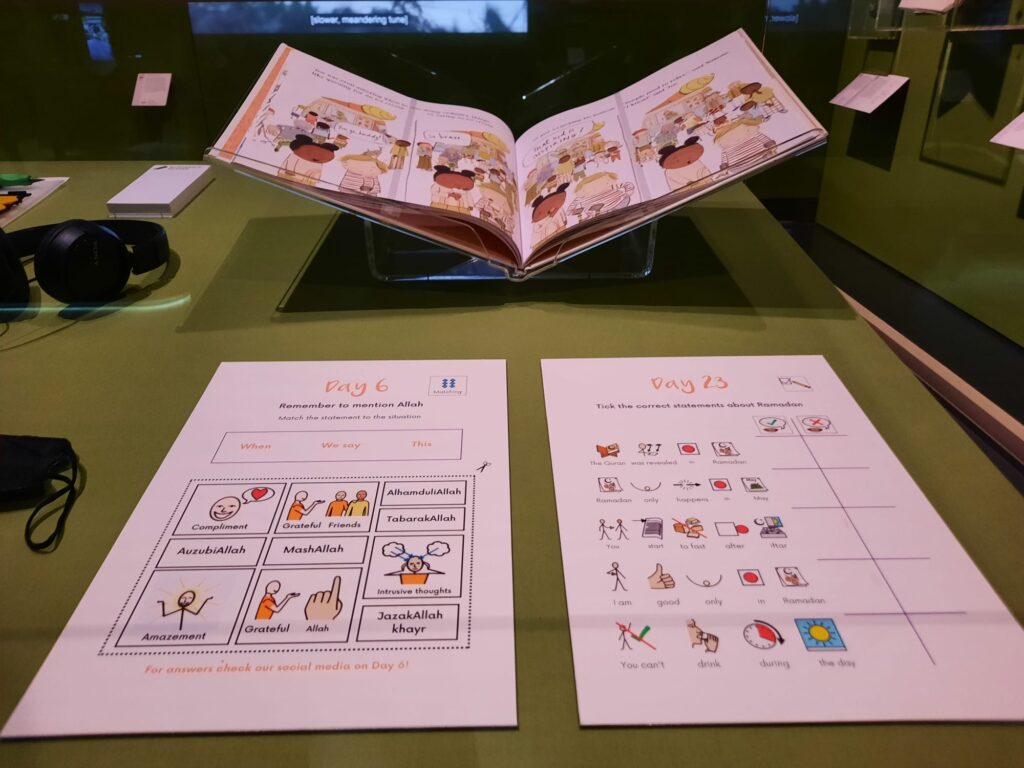

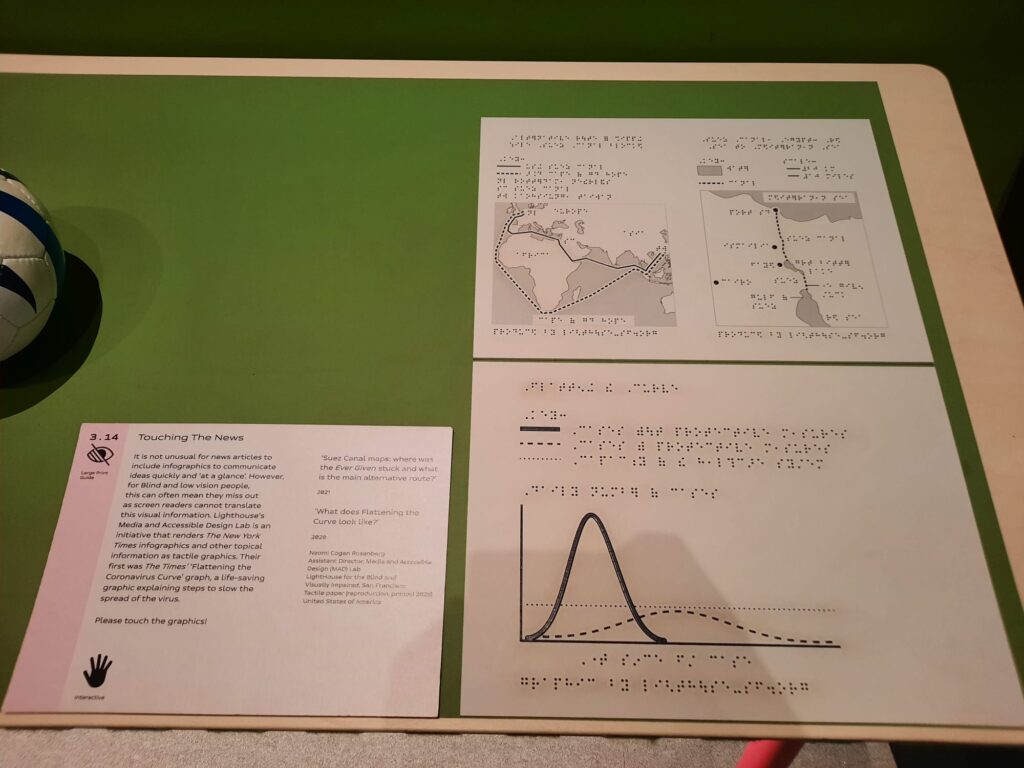

One of the most impressive features of the Design and Disability is its built-in accessibility. From tactile maps, BSL guides, and sensory surfaces, to resting zones, the design team has considered inclusive participation throughout. These features are fully integrated into the visitor flow rather than appearing as afterthoughts. Many reviewers, disabled and non-disabled, saw this as a step in the right direction (see for instance here). On the object side, the selection shows breadth and ambition: from activist zines to an Notting Hill Carnival costume by Maya Scarlette, informed by her experience of ectrodactyly.

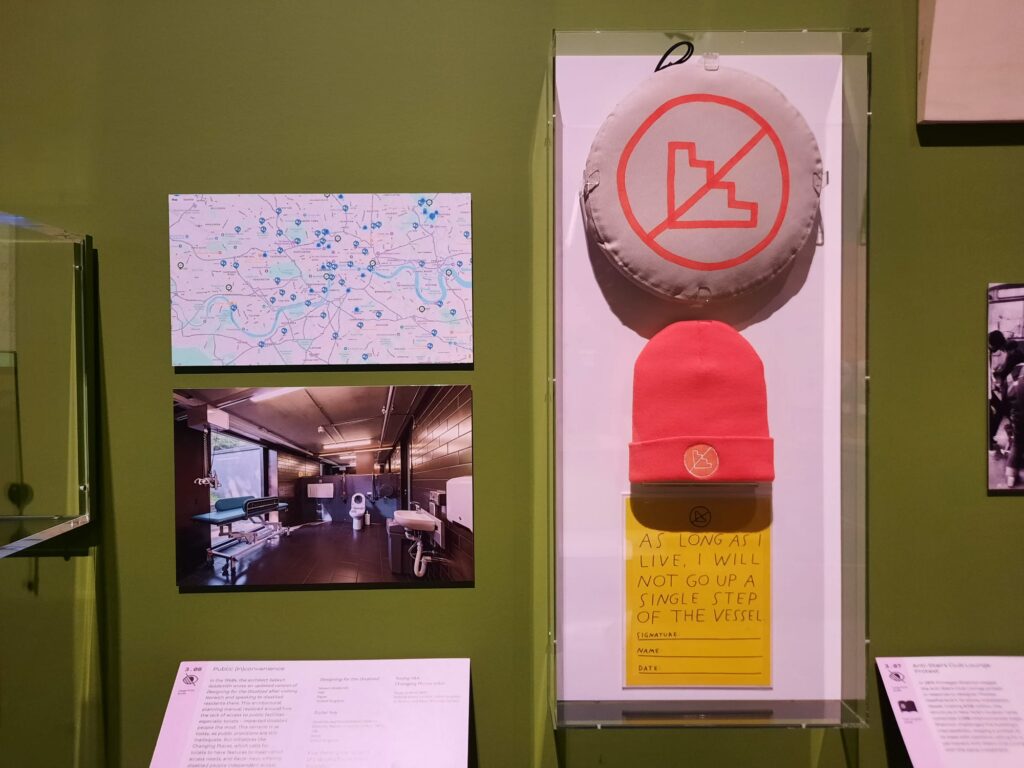

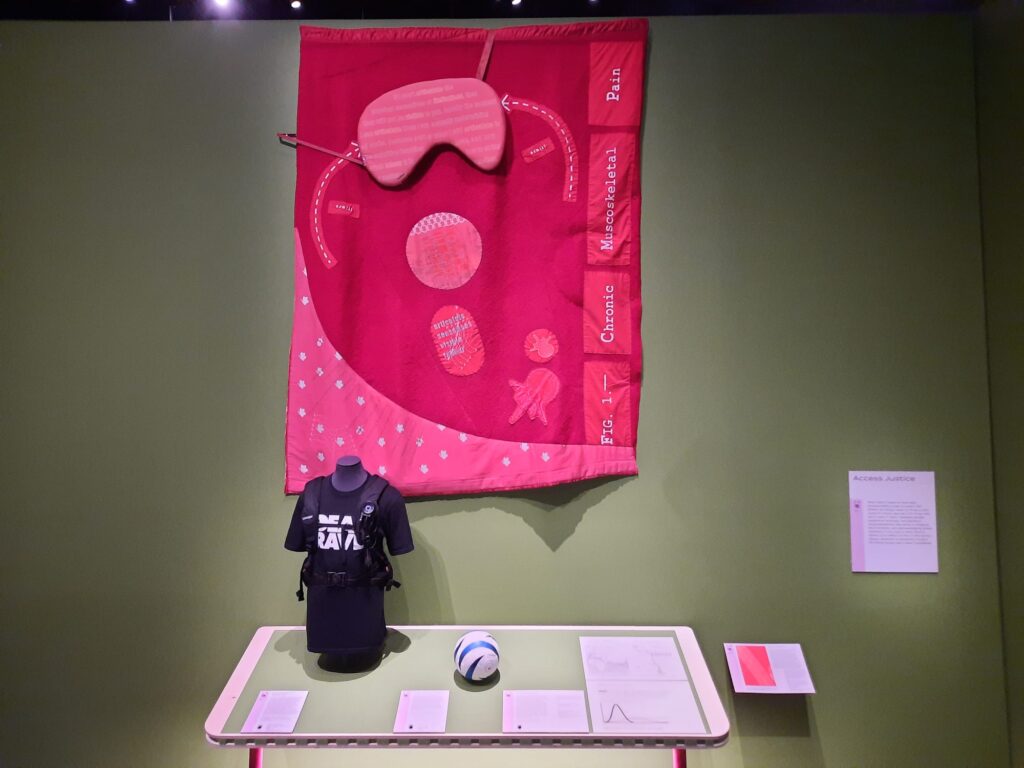

The objects create strong narrative arcs throughout the different sections. ‘Visibility’ is about identity and representation. ‘Tools’ explores adaptation, invention and labour. ‘Living’ folds in spatial, cultural and social activism. This sequencing creates an interesting story about design by disabled people. From different concepts of identity to pushing back against exclusion, the exhibition maps how disabled people have moved from passive users to active designers of their worlds. Its strength lies in making visible what mainstream design hides. Things like the labour of adaptation, the aesthetic of difference, or the politics behind usability. Let’s also recognise here that many of the works on show come from disabled makers themselves, which puts the emphasis on agency. In these respects Design and Disability succeeds: it opens up new conversations and invites reflection, and does these things at museum scale.

Where is the Exhibition Less Successful?

Despite its many successes, I encountered two main areas that merit reflection, especially from the perspective of disability and society. Firstly: there is a reasonably heavy reliance on text-panels, which in turn contain a lot of theoretical framing. The language is fairly dense and prescriptive in places, a finding shared by other visitors including some with a deep knowledge of disability studies. One review written by a disabled academic said the exhibition “lectures from inside a bunker … it tells you what to think”. That raises the question: is this an exhibition open and accessible to all, or does it demand prior (academic) knowledge? Were the curatorial team conceptualising the exhibition from within a particular echo chamber? Museums aiming for inclusive design must also consider interpretive inclusivity.

Secondly: the exhibition has not escaped certain institutional limitations. While the show claims radical intent, let’s remember we’re still talking about a major London museum. Museum norms are in full force: objects as data carriers, formal display cases, ticketed access. The same critic noted free entry for disabled visitors only applied to this exhibition, while broader institutional practices remain unchanged for others running at the same time. From a critical perspective we might ask: how far can one exhibition disrupt larger museum systems of collection, taxonomy and value creation? In comparative terms, the show sits alongside other institutional efforts (for example, activist-oriented exhibitions by smaller museums, like this) that adopt more experimental formats. We need both. Yet here the risk remains that disability becomes a “theme” or a one-off rather than the beginning of structural change.

Despite that, Design and Disability acts as a valuable case-study. It demonstrates what happens when a major institution centres disabled design. It invites further research: how will visitors respond? What lasting institutional changes will result? These questions position the V&A’s offering as a starting point, opening space for deeper institutional critique and future innovation.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Design and Disability on until 15 February 2026