Exploring Monte Gibralfaro, Málaga

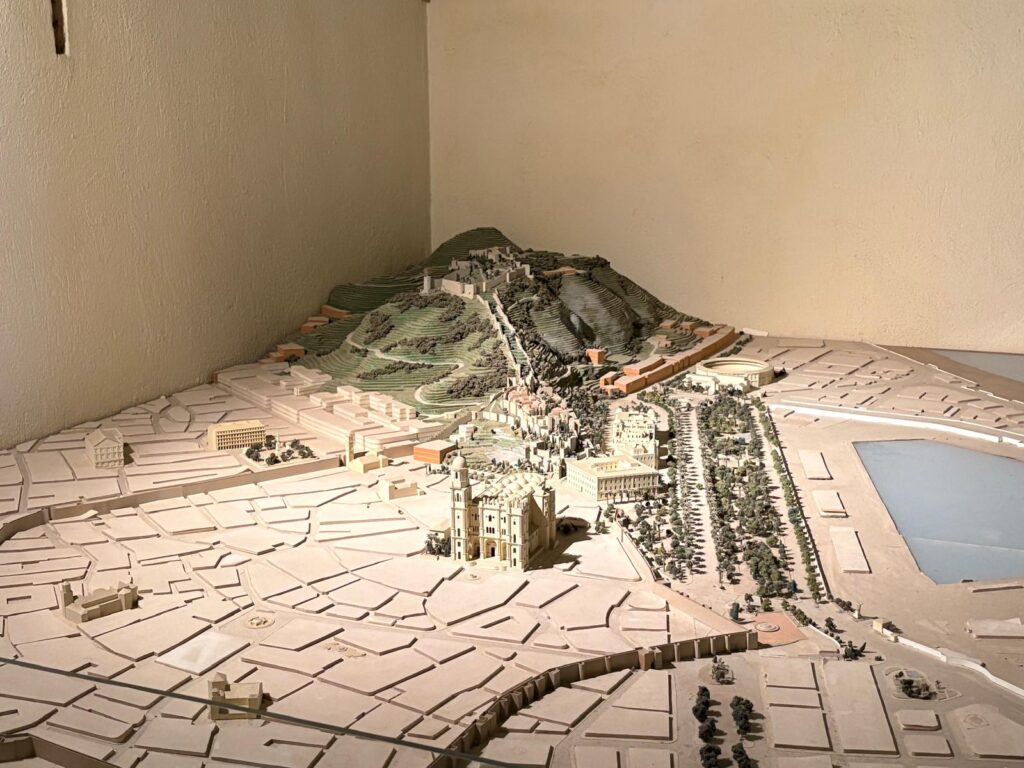

Monte Gibralfaro dominates Málaga’s skyline, and forms part of its coat of arms. What better place to get your historic bearings in this important Andalusian city?

Making the Most of a Weekend in Málaga

A recent trip to Málaga was my second. My first, a few years ago now, was part of a road trip around Andalucía. We admired the African coast from Tarifa, sweated in Seville, and took a detour to Grenada before ending with a few days in Málaga. We were impressed with it as a modern, functional city with an interesting historic core. But the Salterton Arts Review and I were in an ‘off’ period of our formerly on again/off again relationship, so I can’t share any posts with you from that trip.

By extending a business trip to stay for the weekend, I had the chance to remedy some of that. And to get to know more of the city. We’ll get into the history of Gibralfaro in a second. But it’s fair to say that Málaga is one of those cities that peels back like an onion. The most recent layer is of course Spanish, in its different political iterations. Before that Málaga was a Muslim city. Reaching back even further into history we pass layers that are Byzantine, Visigothic, Roman, Carthaginian, Greek, and finally, all the way back at the beginning, Phoenician. Or at least the beginning of historic records. Málaga goes back further than that (the first residents may have been the ancient Iberian Bastetani tribe). It is in fact one of the oldest cities in the world.

And throughout a lot of that history, Monte Gibralfaro has been a place of strategic importance. Today it wears its past proudly. Monte Gibralfaro can be seen from much of Málaga, and is on the city’s coat of arms. And so with a full day to explore, it’s here that my travel buddy and I started. I’m going to retrace the same route we took, from the top of the mountain to the bottom. On the way we will explore three sites that reference millennia of history between them. Just a practical note before we head off, though. Málaga enjoys hot and sunny weather for much of the year. We visited in mid-October and it was hot by UK standards. So smart visitors will do as we did and get the uphill walk out of the way early in the morning. Aim to be at Gibralfaro Castle for opening time.

Gibralfaro Castle (El Castillo de Gibralfaro)

Having taken my sensible advice, started your day early, and walked to the top of the hill, you will find yourself at Gibralfaro Castle. Its position, atop steep slopes and overlooking the city and sea, has made it a strategic spot since the time of the Phoenicians. Rumour (rather than archaeological evidence) has it they had a lighthouse here to aid navigation. The name Gibralfaro actually breaks down as the Arabic Jabal, or mountain, and the Greek Pharos, or lighthouse.

The current version of Gibralfaro Castle dates to the Muslim period, with some later restorations. Yusuf I of Grenada ordered it built between 1344 and 1354. As well as housing his army, it protected the Alcazaba below (we’re coming to that in a minute). It was eventually the most impregnable fortification of its age, and withstood a siege by Isabella and Ferdinand in 1487 for three months. Once under Christian control again, the monarchs placed a tithe on lime, tiles and bricks to help rebuild it. It remained an important military structure until the 19th century, later becoming a prison. It took much of the 20th century to prepare it as a visitor attraction.

Today it is perhaps not the most exciting historic site, but the views are certainly worth the climb. There isn’t much to visit in the interior of the castle (a former gunpowder arsenal houses a small museum), but you can follow the perimeter walls. This affords views over the harbour area, the city, and the countryside beyond. Gibralfaro Castle was once linked to the Alcazaba by the coracha, a protected corridor that was part of the site’s impregnability. Today the same path you climbed up leads back down to the Alcazaba. You can also reach the castle by bus or car.

The Alcazaba

What is an alcazaba, you ask? It’s essentially a citadel. Citadels are normally on high ground and this one does fit the bill, although the castle of course takes prime position further up. If the castle was about military defence, the Alcazaba was about political leadership. We’re actually moving back in time as we go down the hill: the Alcazaba, first mentioned in the 8th century, dates to the Umayyad Emirate. It had military, residential and administrative sections. After the fall of Muslim Málaga, the Alcazaba became the governor’s residence, and was also a royal lodging for King Philip IV in 1625. A century on, military techniques had evolved, and Charles III ordered the demilitarisation of the Alcazaba. It served instead as barracks, and briefly as a prison for gypsy women and children. In the 19th century it became a slum.

Given this eventful history, by the early 20th century, still a slum, the Alcazaba was not in great shape. There was a lot of talk of demolishing it. But, thankfully for us, there was also interest in preserving it, and in the 1930s it became a historic monument. Historian Juan Temboury Álvarez began to restore it, and to realise just what a valuable site it was. An archaeological museum opened on site in 1947, with restoration work continuing until the mid 1960s.

Today, the Alcazaba is one of the best-preserved medieval fortresses in Spain. It’s a great example of Islamic military architecture, but as a mixed-use space it also has the peaceful courtyards and gardens of Andalusian Muslim architecture. I’m not comparing it to the Alhambra, which is on another scale, but it’s definitely evocative. Take your time wandering around, and again enjoy the views from the walls. You can visit the Alcazaba on a joint ticket with Gibralfaro Castle, or separately. And out of the three sites which form this post, it’s my pick of the bunch.

The Roman Theatre (El Teatro Romano)

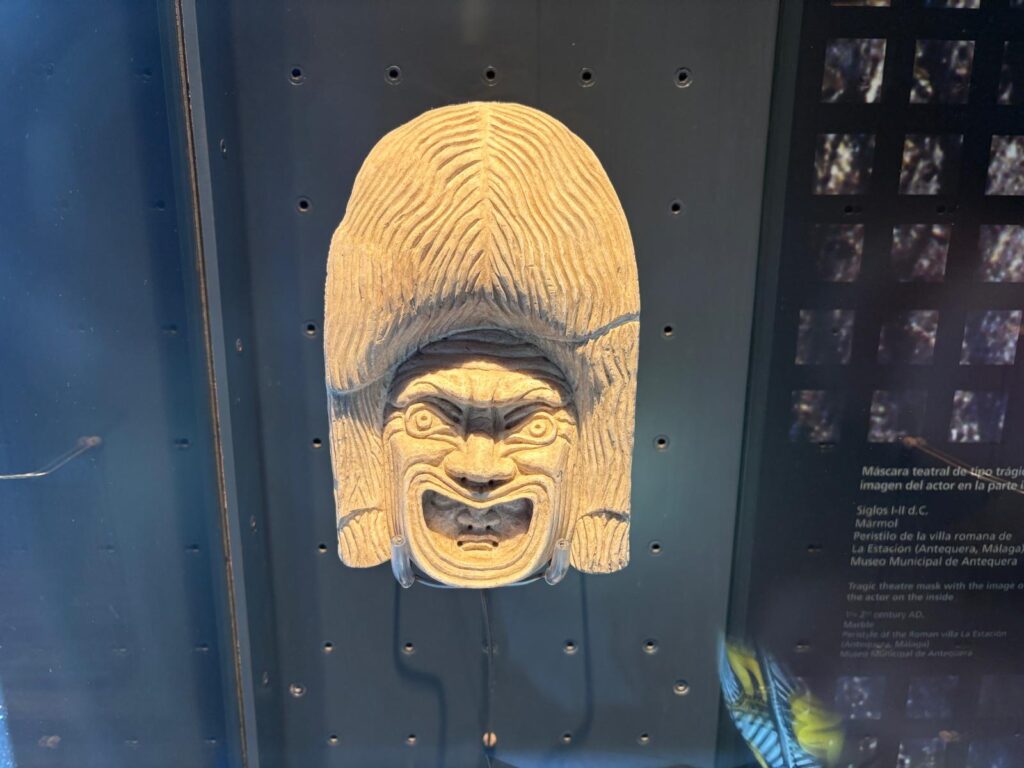

Well done, we’re back at the bottom of Monte Gibralfaro now, and this is our final stop. And the oldest. Málaga’s Roman Theatre dates to the reign of Emperor Augustus in the 1st century CE, and was in use until the 3rd century. After the Romans left, it fell out of use for several centuries until the Muslim period. It unfortunately didn’t resume performances however, but was instead used as a quarry: you can see fragments of its decorative stonework incorporated into the Alcazaba. It was then overgrown, covered, and eventually forgotten.

The Roman Theatre was rediscovered in 1951, during construction of the Casa de Cultura (House of Culture). Although the Casa de Cultura eventually covered a third of the site, a decision was made to scrap a planned garden and excavate and preserve the rest. And in 1995 the Casa de Cultura was demolished to reveal the rest of the site. Restoration was made more difficult as you can’t exactly take the missing bits out of the walls of the Alcazaba. But anyway, in 2017 it reopened, and now hosts performances every summer.

If you’re not in Málaga at the right time to attend a performance, you can have a wander around inside the Roman Theatre. There’s an interpretation centre to one side with a few excavated artefacts. And then you can head into the site itself for a closer look. It’s free to visit, although actually the views from the square in front are almost as good. And that’s actually where I suggest we end this visit: at one of the cafes with a view of the Roman Theatre and the Alcazaba behind it, with Gibralfaro Castle beyond. Already I’ve learned a bit more about Málaga’s unique blend of historic influences than I did on my last visit. And I definitely got my steps in climbing up that hill.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.