Fort St Elmo & National War Museum (Forti Sant’Iermu & Mużew Nazzjonali tal-Gwerra), Valletta

Fort St Elmo spans centuries of history, even predating Valletta. Aim to spend at least half a day here to explore the fort and National War Museum thoroughly.

A Final Stop in Valletta

We bookended our recent trip to Malta with stays in Valletta. For the first couple of nights we stayed in the Old Town, on Merchant’s Street (Triq il-Merkanti). From our breakfast table, we had a glimpse of Fort St Elmo at the end of the street.

I made a first foray here not to visit the fort itself, but for a complicated ticketing manoeuvre. I found out, after booking the trip to Malta, that I had already missed out on the hottest archaeological ticket in town. Gasp! The Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum is just outside of Valletta, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s a really cool Neolithic burial chamber, complete with some original wall paintings. But it is underground, and fragile, and visitor numbers are strictly limited. For those, like me, who don’t sort themselves out in advance, Fort St Elmo is one of two places where you can purchase a small number of next-day tickets. The other is the Gozo Museum of Archaeology. Some people queue for hours, but I was lucky, chanced it 10 minutes before opening, and got my tickets!

Anyway, that is an aside, and a story of how I first came to be at Fort St Elmo. It seemed rude, after that, not to come back and see it properly! And so we did, the following day. Tickets cover both the fort and the National War Museum, not to be confused with the Malta at War Museum, which is over in Birgu (Vittoriosa).

Fort St Elmo – The Early Days

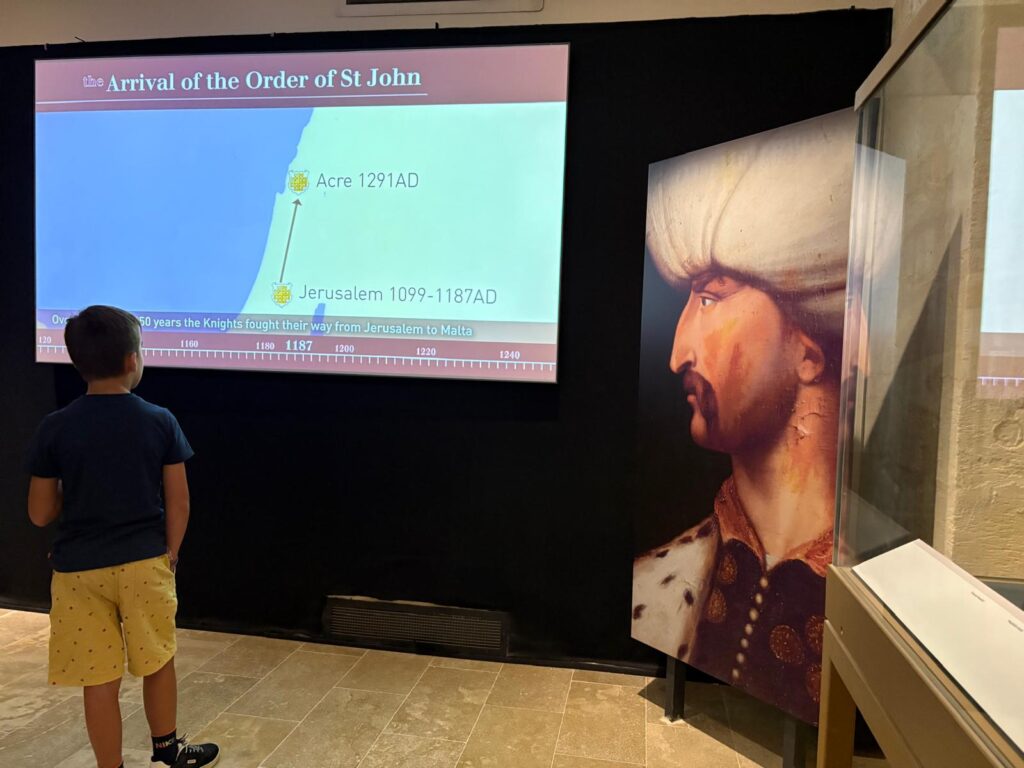

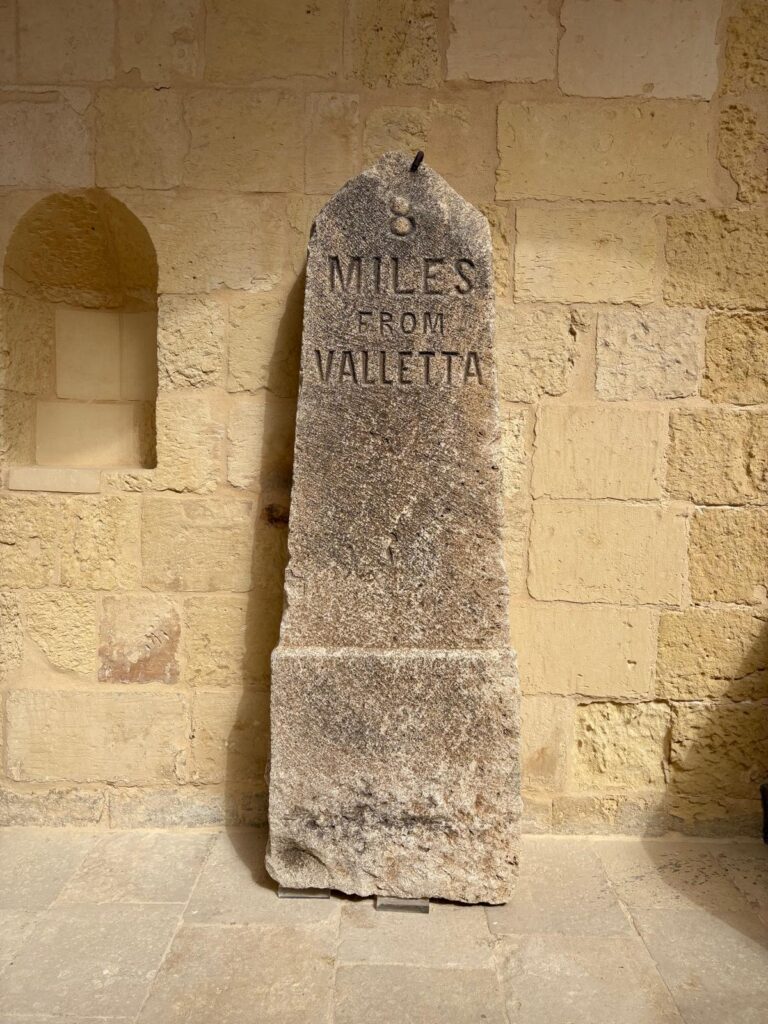

A fortification at the tip of the Sciberras Peninsula (which is more or less Valletta today) pre-dates the arrival of the Order of St John in Malta. There was already a permanent watch post here by 1417. The Aragonese, one of the many different groups to rule over Malta over the years, built a watch tower on Saint Elmo Point in 1488.

The Order of St John arrived in Malta in 1530. Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (who had a real Habsburg jaw, as an aside) granted it to them as a place to live after they left Rhodes following a six month siege by Suleiman the Magnificent of the Ottoman Empire. The Knights Hospitaller, as the members of the Order of St John are also known, immediately understood the strategic importance of the Grand Harbour, and made their capital at Birgu (Vittoriosa). Already in 1533 they had started reinforcing the tower.

In 1551, there was an Ottoman raid on Marsamxett Harbour, which is basically the harbour on the other side of the Sciberras Peninsula from Birgu. For reference, Sliema is one settlement on that side. The Ottoman forces were able to sail into the harbour unopposed, but the raid was ultimately unsuccessful. The Knights Hospitaller nonetheless decided on a major expansion of the fortifications at Saint Elmo Point. They first demolished the tower and began work on a star fort, the best type of defense at the time. By 1565 it had a curtain wall and other clever defensive features.

The Great Siege

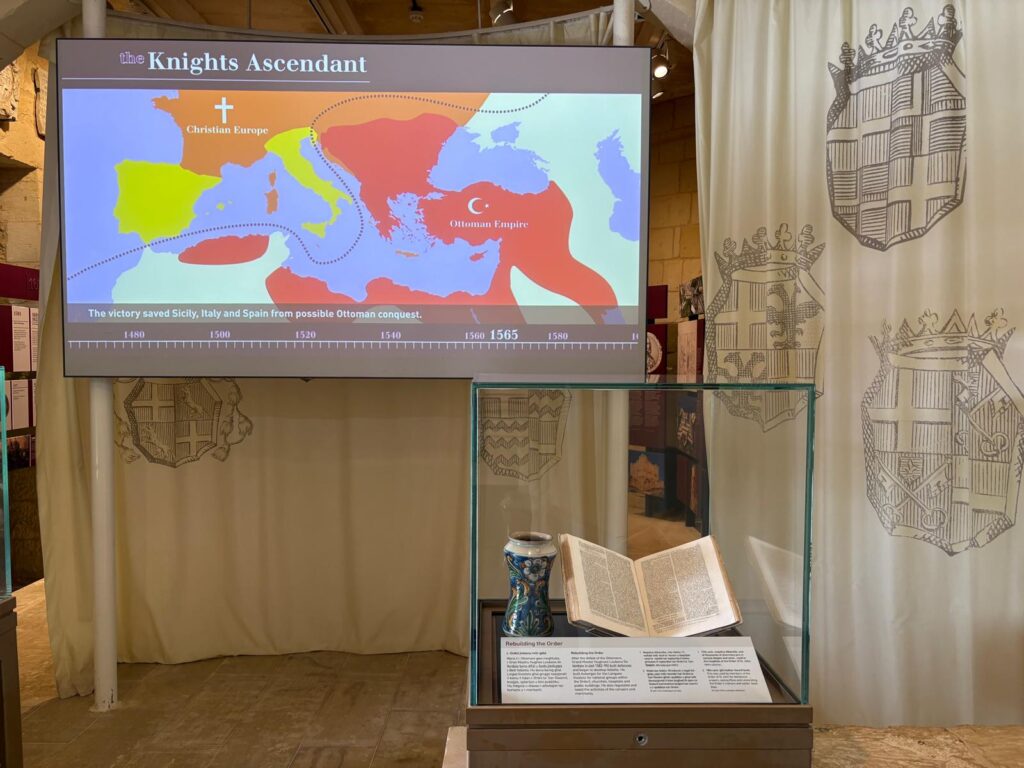

Why did I mention 1565 specifically? Because that is an infamous year in Maltese history, the year of the Great Siege of Malta. The Ottoman forces were back, under Suleiman the Magnificent. Aroung 500 Knights and 6,000 footsoldiers prepared to try to repel them. Their defense was so celebrated at the time that Voltaire once said “Nothing is better known than the siege of Malta.”

Fort Saint Elmo was one of three forts in the area, the others being Fort Saint Angelo and Fort Saint Michael. There had been a sort of running battle between Ottoman forces and the Order of St John since the attempted seizure of Malta in 1551, and the Knights knew that their new base was part of the Ottomans’ long-term strategy to take more territory in Europe. By early 1565, Grand Master Jean de la Valette’s spies informed him an attack was imminent.

The Ottoman armada, one of its largest ever, set sail on 22 March. They were about 40,000 strong in all, against the Knights 6,500. Arriving in May 1565, they planned to take Fort St Elmo first so they would have harbour access for their fleet. They set up camp in two locations, one of which was the Sciberras Peninsula above Fort St Elmo. Once under siege, the situation inside the fort was desperate. The peninsula provided higher ground from which to bombard the few hundred soldiers and knights within, and the fort was quickly reduced to rubble. De la Valette evacuated the wounded and replenished numbers and supplies nightly.

The Ottoman forces seized the remains of the fort on 23 June. They killed around 1,500 defenders, sparing only a handful of knights (a few Maltese fighters escaped by swimming across the harbour). The Ottomans lost around 6,000 men. The overall attempt to wrest control of Malta from the Knights Hospitaller failed, however, thanks to a relief force who arrived in early September. About a third of the Knights, and of Malta’s population, had died defending their territory.

Subsequent Developments at Fort St Elmo

One lesson learned from the Great Siege of Malta was the importance of never allowing another enemy to bombard Fort St Elmo at will from the Sciberras Peninsula. The city of Valletta, named for Grand Master Jean de la Valette, was the result. Construction started in 1566, including rebuilding the ruined Fort St Elmo and incorporating it into the city walls.

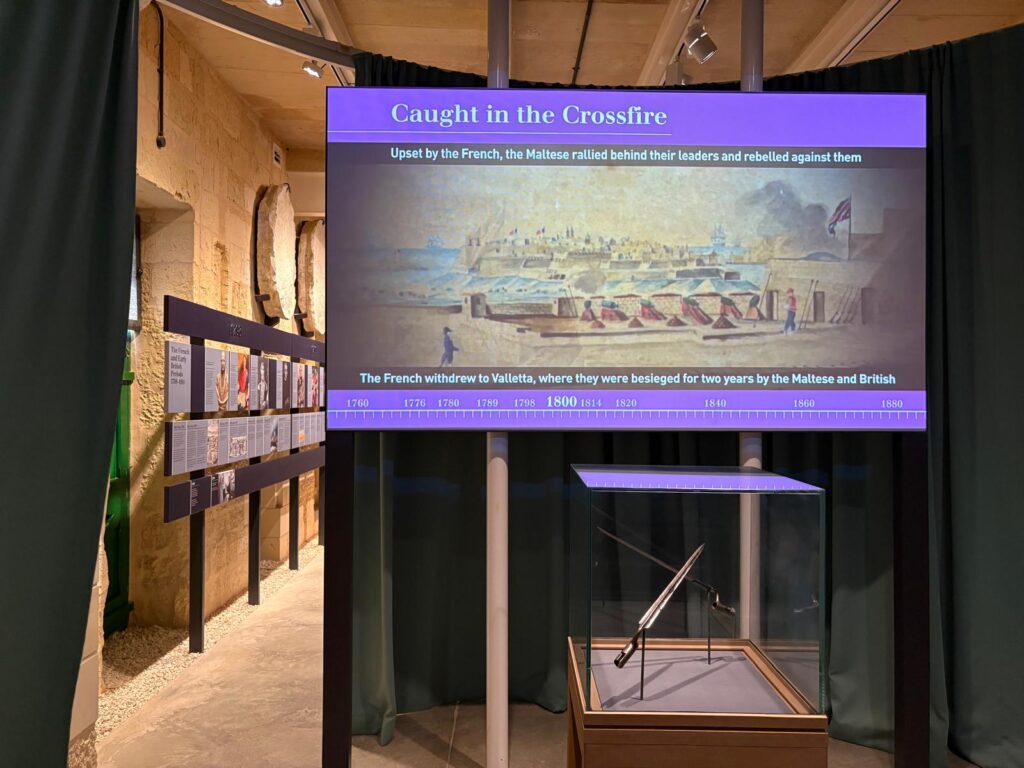

Various changes in the 17th and 18th centuries extended the fort and reinforced its defenses. Notwithstanding, it took only 13 rebel priests to seize it in 1775 in the Revolt of the Priests. The Order of St John quickly recaptured it. Further adaptations were made during the period of British rule, including adding a musketry parapet.

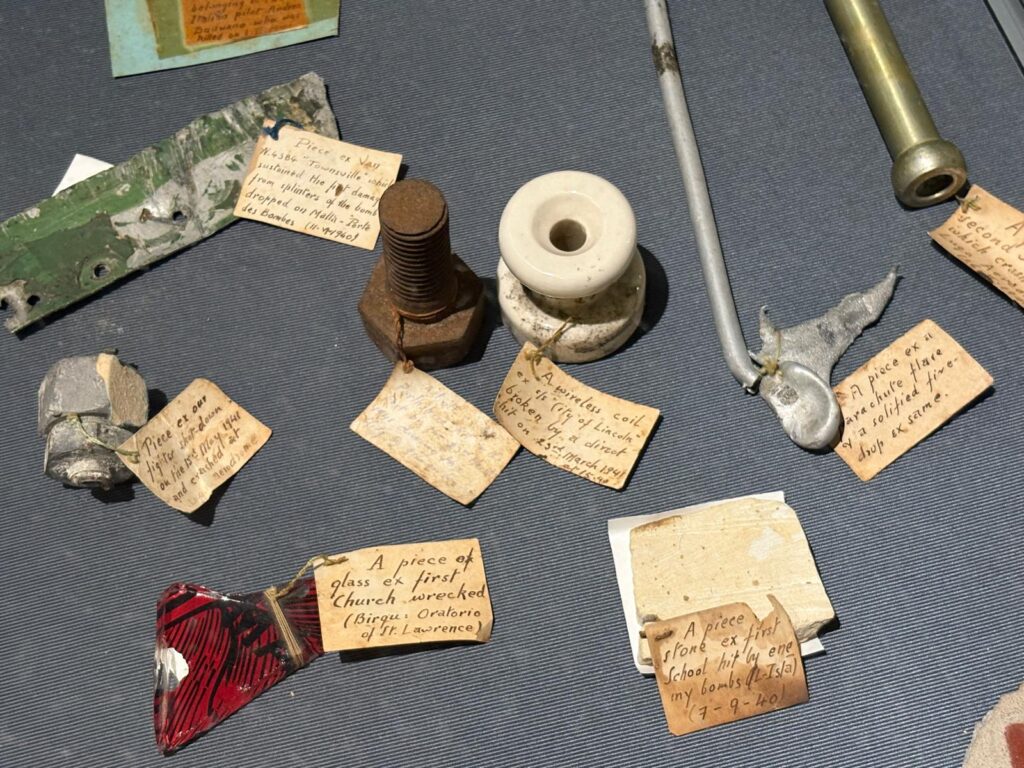

Fort St Elmo again played a role in Malta’s military history during WWII. It was the site of the first aerial bombardment of Malta in 1940. Among those injured was Ċensu Tabone, a future Maltese President. Six were killed. In 1941 the forces at Fort St Elmo thwarted an Italian seaborne attack on the Grand Harbour. Overall, Malta was incredibly hard-hit by bombing during WWII. Fort St Elmo is one of many places which still bear some scars.

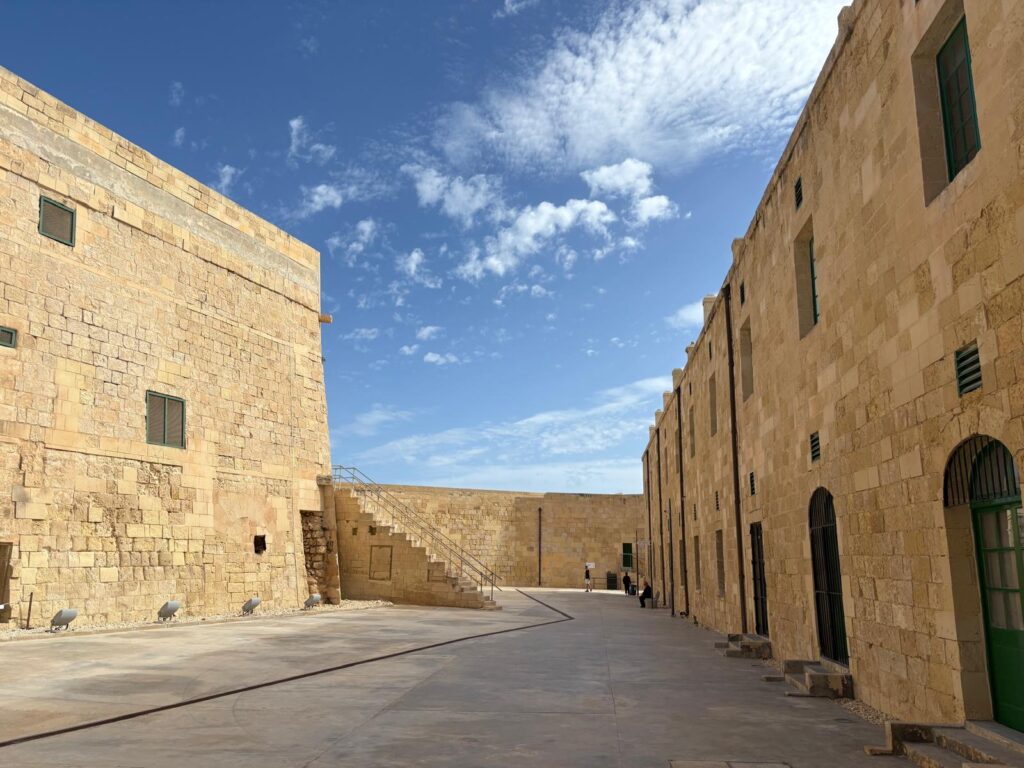

The Royal Malta Artillery continued at Fort St Elmo until 1972, when it ceased to be an active military site. It has been home to the National War Museum since 1975, but other parts of the fort started to fall into disrepair. In 2008 the World Monuments Fund placed it on their watch list of the 100 Most Endangered Sites: a combination of neglect, lack of security, and exposure to the elements. Major restoration work began in 2009 and was completed in 2014. Visitors today, however, will notice that the lower fort, which was formerly a prison (and the shooting location for the 1978 film Midnight Express) has since returned to a dilapidated state. This section is not open to visitors.

Visiting Fort St Elmo

Despite the changes over the centuries to Fort St Elmo, it retains today a star fort shape. Star forts were the preeminent defense during the Early Modern period, in which gunpowder came to the fore in warfare. Star forts were very flat, with triangular or lozenge-shaped bastions at the extremities. Their walls were thick, to withstand cannon bombardments, with the bastions providing firing lines from multiple angles.

From the very beginning of a visit here, the space is uniquely Maltese. Il-Fosos are historic grain stores, insurance against food scarcity on these water-poor islands. They are subterranean, capped with heavy stones that were once sealed with pozzolana, a reddish-brown, cement-like material. I first saw them in the plaza in front of Fort St Elmo, and then again in Floriana in front of St Publius Parish Church. If you didn’t know better, you would think they are columns lopped off at the base. It makes for an interesting entrance point!

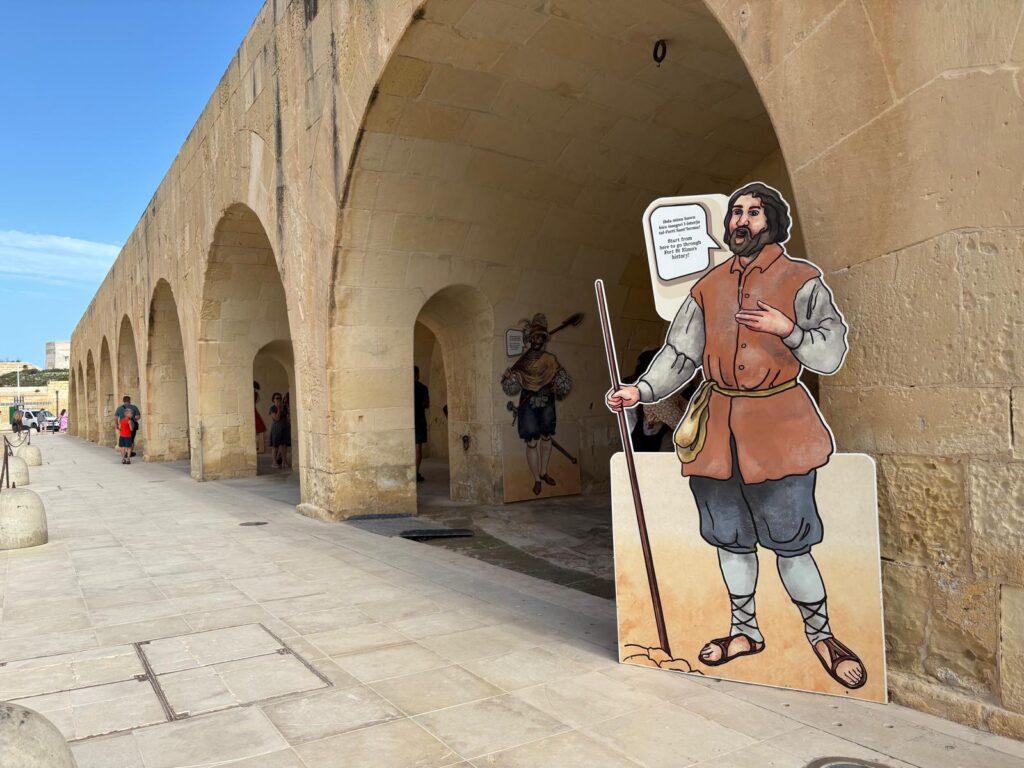

Once inside the fort (via the ticket office I was already familiar with from the day before), there is a lot to see. As well as bastions and other defensive parts of the building, there are lookouts, a chapel, and a sort of timeline of different phases of the fort’s history told through a series of characters. Then there is the National War Museum. Split over seven sections, it tells the story of warfare from the earliest archaeological evidence to the post-WWII period. There’s also an audiovisual show, normally, but this was closed when we visited.

To see it all thoroughly would be the best part of a day. We went at a fair pace, and it was still around half a day to visit almost everything (the AV show I mentioned already, and one other section was closed due to high winds). For military enthusiasts, I imagine it’s a dawn ’til dusk sort of activity!

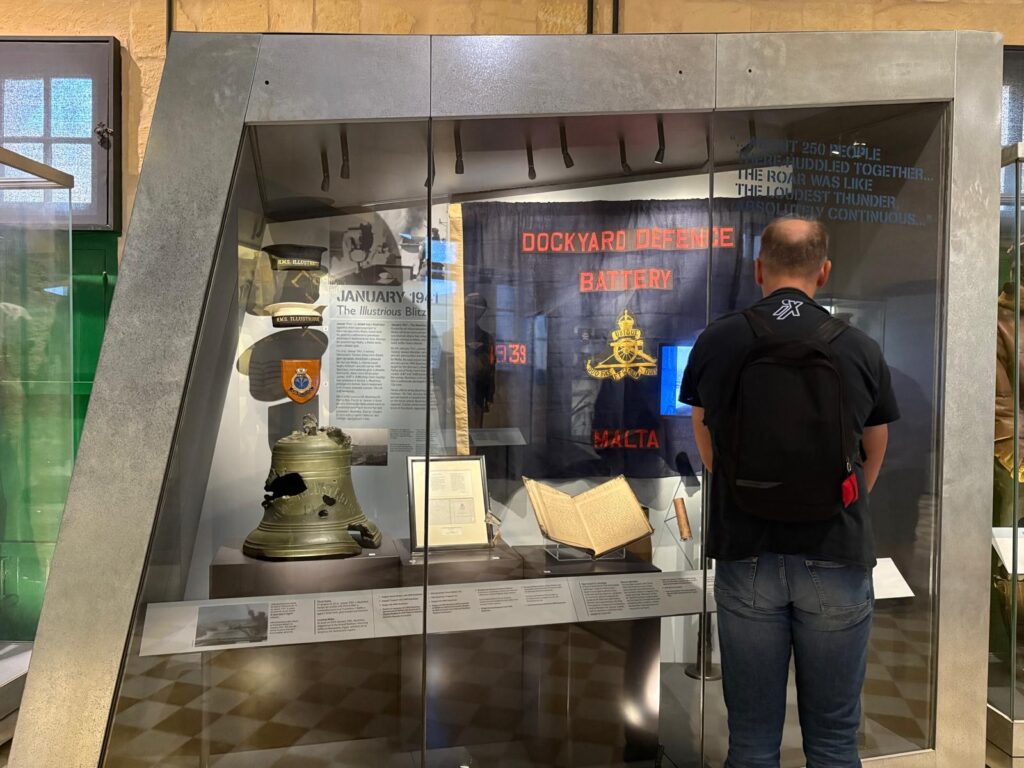

The National War Museum

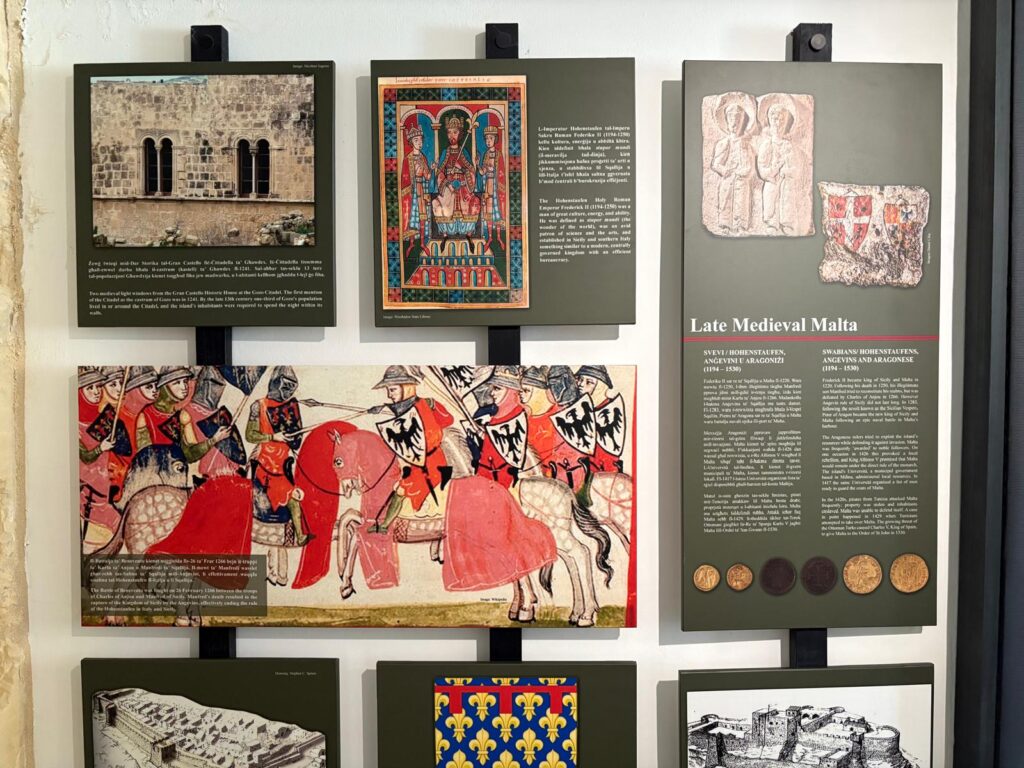

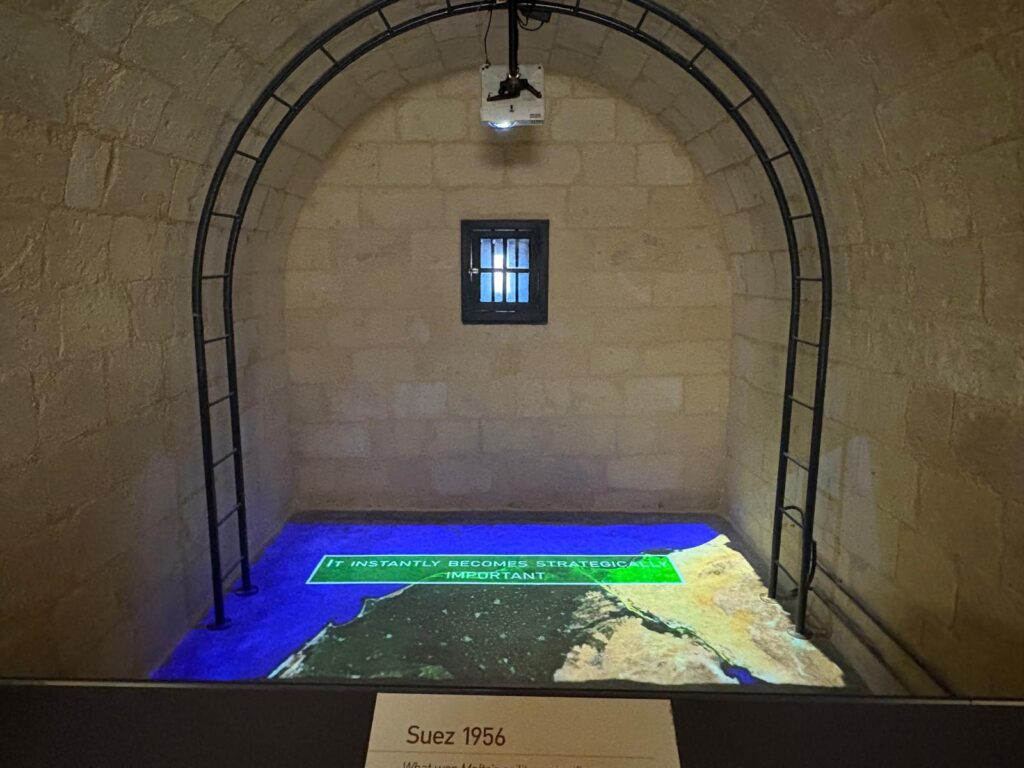

The National War Museum is what visitors will spend most of their time on inside Fort St Elmo. Divided into seven sections, it covers millennia of history in terms of Malta and warfare. Not entirely equitably. The first section covers everything from prehistory to the late Middle Ages, while the Great Siege and WWII each get their own section.

Prehistory is an interesting inclusion in the museum’s story. It seems a bit of a pretext to include some archaeological artefacts, if I’m honest. Especially when the evidence points to there being little in the way of warfare or military capabilities during the time of Malta’s Neolithic inhabitants.

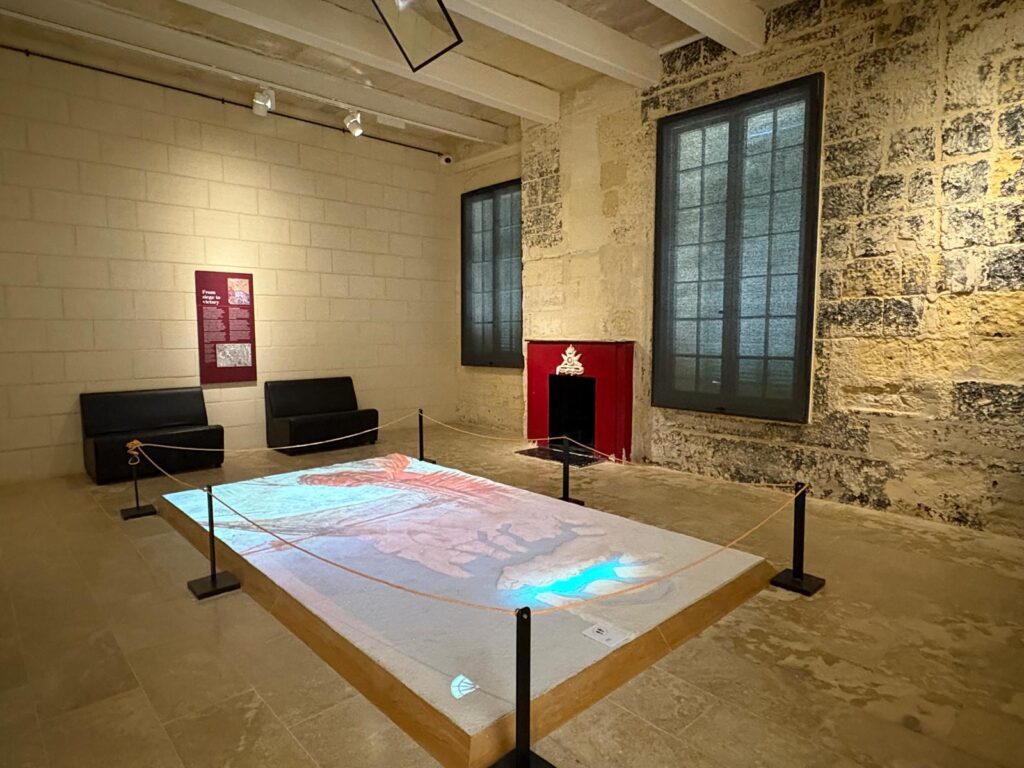

Moving through the galleries, there is a good mix of objects and interpretation to help build up a picture. There is relatively little to actually show from the period of the Great Siege, for instance (aside from some cannon balls), but there are some illustrations which have been used to create compelling AV displays. For later conflicts, from the arrival of French forces in Malta through the World Wars, the displays take a more object-centric approach. This is typically a blend of military and social perspectives: the people impacted by war as well as the strategies, skirmishes and battles. The museum paints a good picture of what the people of Malta went through in WWII, as they faced bombings and shortages of supplies. The George Cross awarded to the entire population for their bravery is one of the objects on display.

The fragmentation of the museum amongst different buildings does make it a little hard to create one narrative thread. It’s like visiting seven small museums on separate topics. But each of them is interesting in its own right, and whoever is the faster of your group will have the opportunity to sit and admire the fort from different angles while they wait for the others to emerge and start heading to the next section.

What Else is There to See?

We’ve now covered most of what there is to see at Fort St Elmo. But there are a couple of other things I’d like to mention before we wrap up.

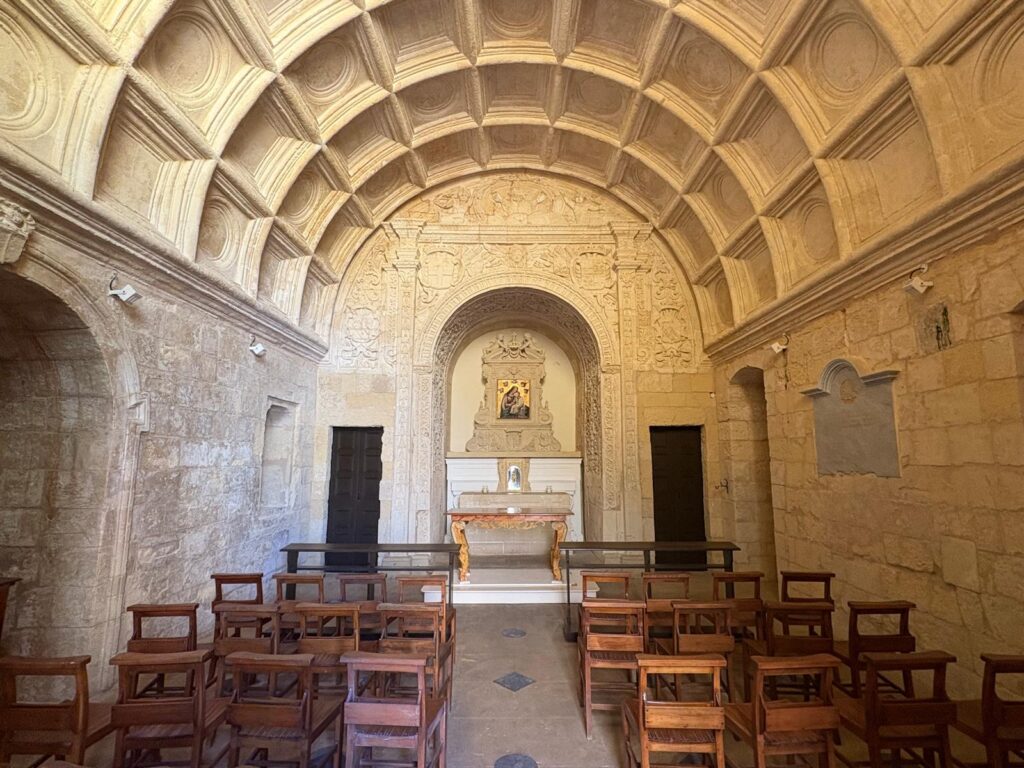

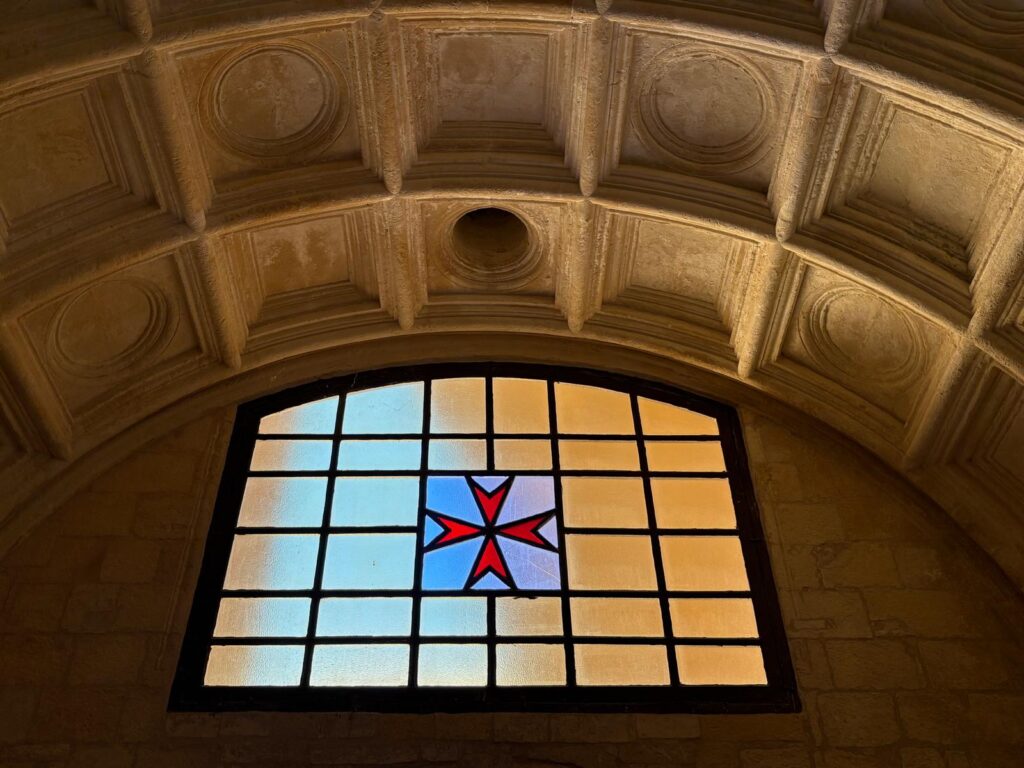

Firstly, I did briefly mention a chapel before, but would like to expand on that a little now. The Chapel of St Anne actually pre-dates the fort, with documentation dating to the 15th century. That makes it the oldest building on the Sciberras Peninsula. Its current appearance is more 17th century, though, and its original dedication may have been to St Elmo, AKA St Erasmus of Formia (that would make sense). During the Great Siege in 1565, the chapel was the site of the defenders’ last stand, having withstood the Ottoman assault for a month. The chapel’s architectural style is Renaissance/Baroque, yet it is simple in design. A barrel-vaulted, coffered ceiling is the main feature, along with a 15th century Madonna and Child icon.

The chapel is definitely worth a look. I was less convinced by our next stop, which is the series of arches opposite the Porta del Soccorso. These I also mentioned a little earlier. Inside each arch is a representation of a character from a different period. Together, they retell the story told within the fort. But why? I suppose it’s targeting younger visitors? That’s probably the case, even though the interpretation here is mostly text-based. The other explanation is just that it was something sensible to put in an otherwise unused space within the fort.

And lastly, I’ll mention one attraction at Fort St Elmo I didn’t get to see for myself. The AV display in the cavalier seems to be a highlight, but was unfortunately closed when I visited. The company who collaborated with Heritage Malta on the AV aspects of the fort, Sarner, describe an immersive display featuring holographic figures, as well as projected seas, explosions and gunfire. If you have the chance to see it, I suggest you do!

Final Thoughts

We’ve come now to the end of our half day at Fort St Elmo. Before we even entered the fort, we were learning about Malta’s history of scarcity and resourcefulness through the grain stores in the plaza. On entering the fort, we came across the oldest building on the Sciberras Peninsula.

But the stories told here go back further still: the National War Museum traces military history over millennia. Across seven different spaces throughout the fort, we learned about Malta’s wartime record from its earliest days to the post-WWII period. Fort St Elmo is often at the forefront, whether that’s the brave defense the Knights and soldiers put up during the Great Siege of Malta, or being the unlucky site of the country’s first aerial bombardment during WWII. Seeing a George Cross awarded to an entire population is a moving tribute to the civilian experience of war.

Elsewhere at the fort, you get a sense of life here in the 20th century. The lookout post must have been a tense but tiring place to be, staring out to sea in the hopes of spotting the enemy’s approach. The wind whips across up here: I could see why at least one other section was closed due to high winds when we visited. The views from the bastions are impressive, though. Make sure you walk right around the fort and take a good look.

Military history is not my greatest love. So when we went over to Birgu (Vittoriosa), I skipped Fort St Angelo. One fort felt like enough during a week in Malta. But Fort St Elmo gave me a good grounding in Maltese history, and I’m glad I chose to visit it. Its central location makes it a good pick for visitors to Valletta, even those like myself who are not military history buffs (but love a historic site in general).

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.