Museo Carmen Thyssen, Málaga

The Museo Carmen Thyssen presents a private collection of mostly Andalusian, 19th century art. A great way to learn more about this region and its representation in art, just get ready for a lot of genre paintings!

A Foray into Málaga’s Museums

Today we continue our exploration of Málaga, which we started in my last post with a trip to Monte Gibralfaro. That was more a history lesson, taking in three historic sites. But while I was in the city for the second time I also wanted to check out its museum offerings.

But what to pick? Being Picasso’s home town, Málaga has both a Picasso Museum and a Picasso’s Birthplace Museum. I visited one of these last time I was here: I think the former. But as I said when I was last in Barcelona, there’s only so much appetite I have for Picasso museums. So not those, then. How about the Málaga Museum, in a former customs building? Interesting, and perhaps one to see in future. There’s a Centre Pompidou outpost over by the harbour. I am interested in museum outposts (we will see another in Málaga very shortly). But what I went for in the end is not quite an outpost, but an offshoot perhaps, of a famous collection.

The Museo Carmen Thyssen was my pick, in the end. This was partly practicality: the museum is in the Old Town and was thus walking distance from my hotel. And I knew the focus was on Spanish art and was interested to see that. But, having visited the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional some years ago in Madrid, I also wanted to understand more about how this museum fits into that larger picture. Which we will start to understand now, with an overview of a family and their art collection.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection and Carmen Thyssen

The Thyssen-Bornemisza story doesn’t actually start in Spain. Briefly going back a couple of generations, Heinrich, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon et Impérfalva, was a Hungarian-German entrepreneur and art collector born in 1875. He was actually born a Thyssen, heir to an industrial family, and married into the noble part of his name. He started an art collection based around Old Masters, buying up a lot of paintings at good prices during the Depression.

Heinrich’s son Hans Heinrich August Gábor Tasso Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon, Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza was born in the Netherlands in 1921. He continued the family art collection, and built a museum for it in Lugano in Switzerland, where he lived. However, in 1988 Hans Heinrich applied to extend the museum, and was refused permission. He took umbrage at this, and decided his collection needed a new home that better appreciated it.

Enter the Baron’s fifth wife, María del Carmen Rosario Soledad Cervera y Fernández de la Guerra, Dowager Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza de Kászon et Impérfalva (this family don’t do short names). Born in Sitges in Spain, Carmen’s influence was decisive in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection moving to Madrid. Situated next to the Prado, the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museo Nacional fills gaps in the Spanish national collection. Starting as a private museum, the Spanish government purchased 775 works for $350 million in 1993. In 2021, the government also reached an agreement with Carmen Cervera, as she’s known, for a long-term loan of parts of her collection.

Because, you see, Carmen Cervera became an important art collector in her own right. And so we arrive at the Museo Carmen Thyssen, which, as the name implies, displays her own art collection. Its focus is 19th century Spanish painting, primarily Andalusian. The purpose-built museum, incorporating the Baroque 16th century Palacio de Villalón, opened in 2011.

A Wealth of Andalusian Painting

As ever, that brief amount of context-setting is fairly light on the detail. So it’s time now to look in more depth at what a collection of 19th century Spanish painting, primarily Andalusian, encompasses.

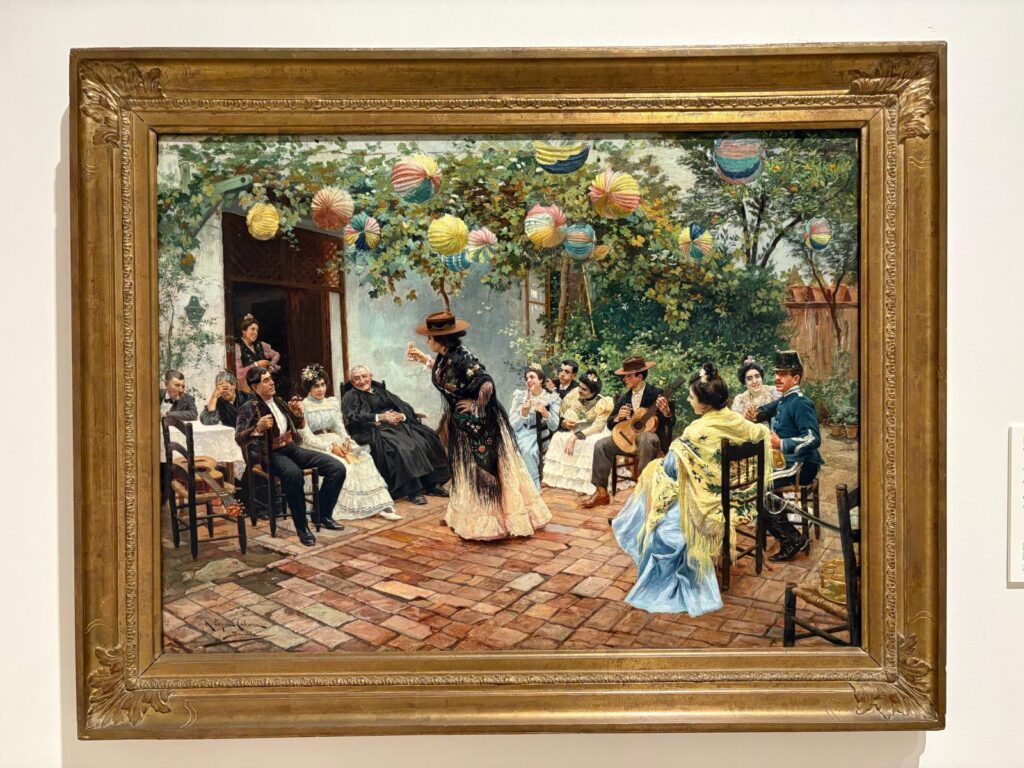

The first thing I will say is I saw an awful lot of what I would call genre paintings. The simplest definition of this term is “paintings which depict scenes of everyday life”. Genre paintings originated in what is now the Netherlands in the 17th century, featuring a lot of peasants and drinking in taverns. In the 19th century Andalusian context it still means a lot of peasants, but in sunnier climes wearing brighter clothing. The Museo Carmen Thyssen features numerous scenes of dark-haired beauties, traditional festivities and dances, and humorous or romantic meetings. The 19th century was a time when national or regional identity was developing in many parts of Europe, and the paintings give a sense of trying to capture a particular way of life at a moment of great change, particularly through industrialisation.

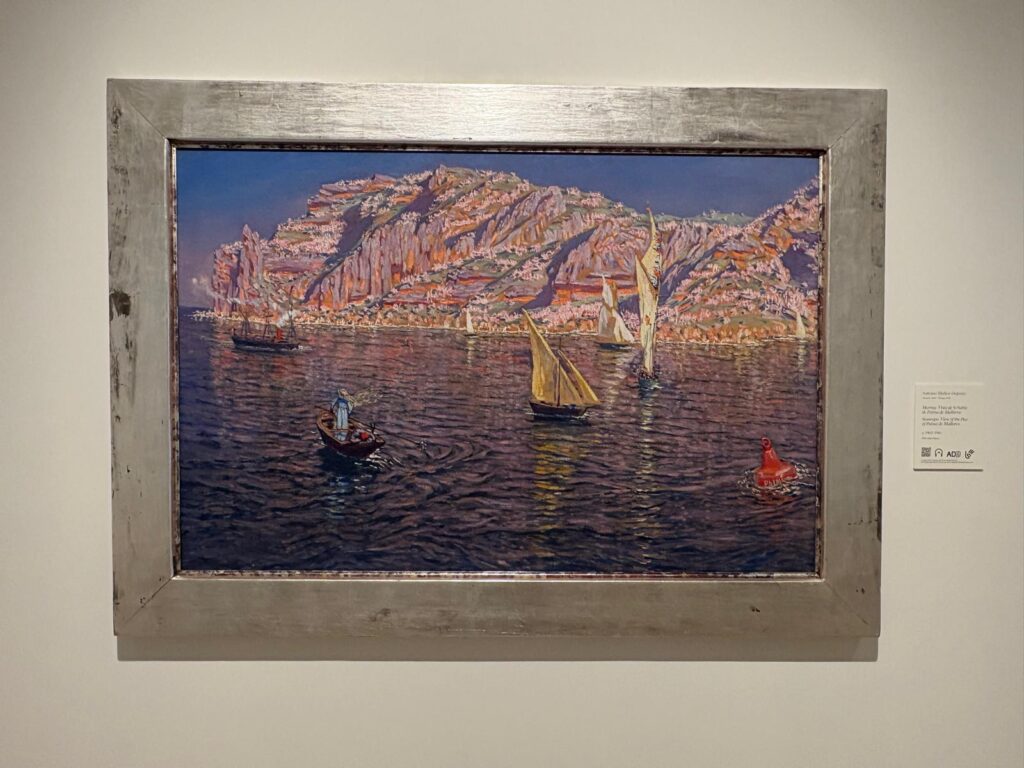

The collection display is largely chronological and thematic, so there are so many of these scenes it’s hard to take them in after a while. Luckily modern influences start to creep in. Some of the canvasses become light and airy à la Sorolla. Others focus on landscape, with experimental colours and presumably plein air inspiration in some cases. But we do keep coming back to that particularly Spanish preoccupation: dancers, beauties and other characters populate canvasses in new ways – bolder, new perspectives, brasher depictions of modern life. The collection ends before we get to truly modern works and movements like Cubism or Surrealism, as deep as their Spanish roots may be.

There’s one small aside within the collection: a single room with older artworks. Devotional works, including sculptures. A single work by Francisco de Zurbarán. A little incongruous, but since the building has a few nooks and crannies, it doesn’t seem too strange to have a little section devoted to what came before. Finally, the top floor is a space for temporary exhibitions: more on this in a moment.

Final Thoughts

Having selected the Museo Carmen Thyssen as one of my two museum choices during my limited time in Málaga, would I recommend you do the same? Perhaps. It’s a great place to understand more about Spanish art, and see the Andalucía of yesteryear. But as I said above, there are actually only so many genre paintings of Spanish villages you can see before they start to blend into one. Perhaps a little less of that, and a small foray into what Málaga’s most famous son Picasso did in terms of artistic boundary-pushing, might make for a slightly more engaging museum overall.

But otherwise it’s a nice museum to visit. The building is an interesting mix of old and new – don’t forget to check out the courtyard on each level, which sometimes has views of neighbouring buildings, or the odd painting or side room of the collection. It’s also very handy, being in the old town. You don’t need to set aside a whole day, or even a half day. A couple of hours will do to peruse and take in this small part of a much wider family art collecting effort.

Continue reading to learn about the temporary exhibition that was on during my visit.

Temporary Exhibition: Telluric and Primitive

When I visited in October 2025, the temporary exhibition at the Museo Carmen Thyssen was Telluric and Primitive, or Telúricos y primitivos in Spanish. What on earth does telluric mean, you ask? Good question, I didn’t know either. Let’s take a look at the Museo Carmen Thyssen website to understand more:

“The earth and a primordial language of signs and basic forms – or, as we have defined it in this exhibition, the telluric (terrestrial or geological) and the primitive (primordial) – offered two paths of renewal starting from the very first episode in modern Spanish art (the 1920s and 1930s). Persistent and recurrent, they constitute an idiosyncratic substratum of Spanish avant-garde art that is still recognisable today.”

https://www.carmenthyssenmalaga.org/en/exposicion-actual

I was talking above about how the permanent display ends before some of the big hitters of Spanish modern art, but it seems that temporary exhibitions are the way they incorporate that narrative. Tàpies, Chillida, and Miró are all here, as well as more recent artists like Barceló. In fact, the exhibition is an interesting blend of modern and contemporary art, as well as of media: paintings, sculptures, a little bit of textile work.

And what about the subject matter? It’s intriguing. Essentially, the exhibition looks at varying influences on modern Spanish art, per the quote above. At a time of great rupture in art and society, many artists turned to very literally grounded, earthly influences like prehistoric art and indigenous art (I’m less comfortable with the term ‘primitive’). And have continued to do so. How they achieve this varies. Some used earthy tones and pigments. Others, more literally earthy materials. Some evoked the rounded forms of neolithic sculpture, or the geometric shapes of non-Western art and objects. Some artists developed their own language of signs and symbols, appealing to a shared understanding transcending language or modern culture.

The exhibition is fairly small, but engaging. It stands apart from the wider museum collection in terms of period and subject matter. And also physically, with deep red walls marking the temporary exhibition space. It’s included with entry tickets, so is worth spending some time in if you visit the Museo Carmen Thyssen.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Telluric and Primitive on until 1 March 2026

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.