St Paul’s Cathedral (Katidral ta’ San Pawl) & Its Museum, Mdina

The site of St Paul’s Cathedral has been the heart of Mdina since before it was Mdina! What better place to start getting to grips with Malta’s historic capital?

A Daytrip to Mdina: Where to Start?

In my last post, I described a daytrip to Mdina and Rabat, covering a bit of history as well as ideas of what to see and do. The Urban Geographer and I took just such a daytrip during our recent trip to Malta. Only I had not read any such helpful guides, and so we arrived without much of a plan. Getting off the bus in what must technically be Rabat, we followed the crowd and found ourselves outside Mdina’s city walls. Mdina first, then! And after a bit of wandering within those walls, we found ourselves outside the city’s cathedral.

I’d learned through a combination of skim-reading my guidebook and visiting St John’s Co-Cathedral in Valletta that Mdina had remained the centre of religious authority in Malta even after the capital moved first to Birgu and then to Valletta. Or the centre of Maltese religious authority, I should say. Because the local population and the Knights Hospitaller had separate religious authorities. The reason the Co-Cathedral is now a Co-Cathedral is that it is home to both, as of the 19th century. Before then it was the cathedral of the Order of St John only, and the cathedral here in Mdina was the centre of Catholicism in Malta. Today the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Malta is shared between the two. A rather convoluted history but it meant visiting the cathedral seemed like a good idea!

Mdina Metropolitan Cathedral, also known as the Cathedral of St Paul is, like many of Malta’s important churches, a ticketed affair. And tickets include entrance to both the cathedral and the Mdina Cathedral Museum. With that in mind we purchased our tickets, saw the cathedral, and then doubled back to see the museum. Let me tell you a little more about both now.

St Paul’s Cathedral, Mdina: A Brief History

In the opening to this post I said that this place has been important to Mdina since before it was Mdina. But just what did I mean by that? Well, one clue is in the cathedral’s dedication. If you’ve been reading some of my prior posts, or you know something about Malta, you might know that St Paul was shipwrecked in Malta in about 60 CE. Or probably was – it seems fairly likely the shipwreck happened, and Malta is about the most likely location for it. The legend is very important locally, however. Mdina at that time was the Roman city of Melite. It was bigger than today’s city – parts of today’s Rabat were then within Melite’s limits. And it’s in Rabat that you can visit the grotto St Paul is supposed to have stayed in.

Although an accident brought him here, St Paul did not waste any time in Malta. He met the local leader, Publius, performed some healing miracles, and converted Publius (and many others) to Christianity. Publius later became Malta’s first Catholic saint. And guess where Publius’s home was? At least in legend? Yes, that’s right, just where the cathedral stands today. There are remains of a Roman domus in the crypt, so who can say?

The first cathedral here was dedicated to the Virgin Mary. This cathedral fell into disrepair when the city was largely abandoned, and was used as a mosque during the Arab period. When Christianity was reestablished in the islands the cathedral was too, in Gothic and Romanesque styles. In 1679 Bishop Miguel Jerónimo de Molina appointed architect Lorenzo Gafà to replace the medieval choir with a fashionable Baroque one. A few years later Gafà was able to do much more, after an earthquake severely damaged the cathedral in 1693. The surviving choir and sacristy became part of a new cathedral, Gafà’s masterpiece. Another earthquake in 1856 did some damage to frescoes in the cathedral’s dome.

Inside and Outside the Cathedral

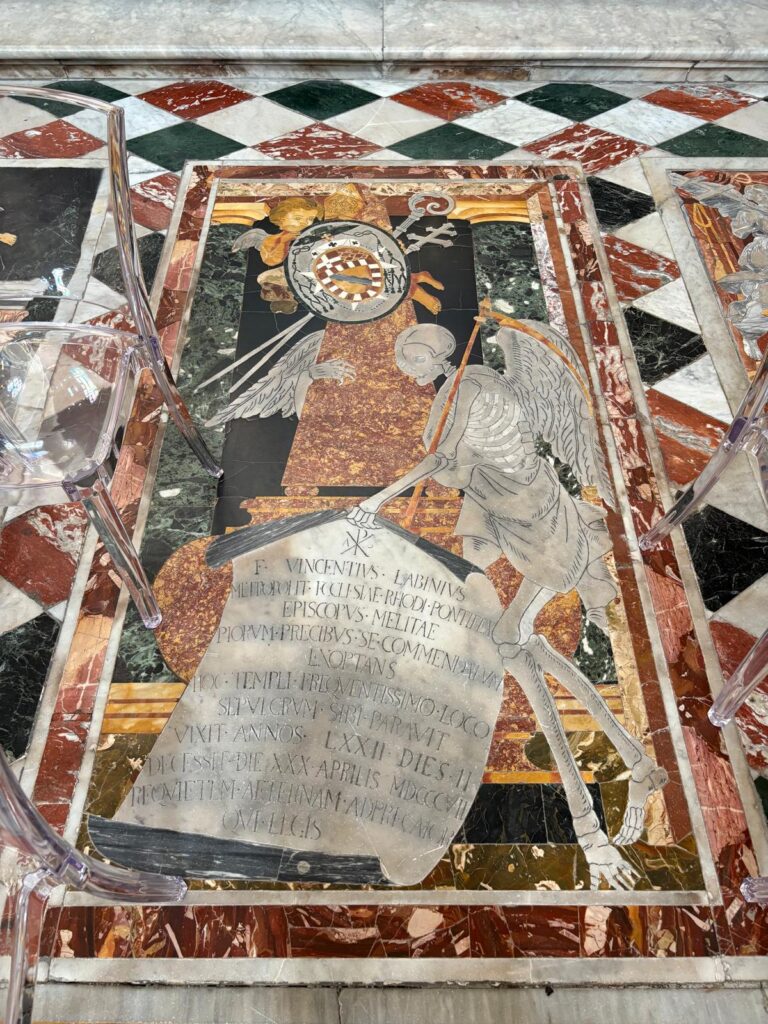

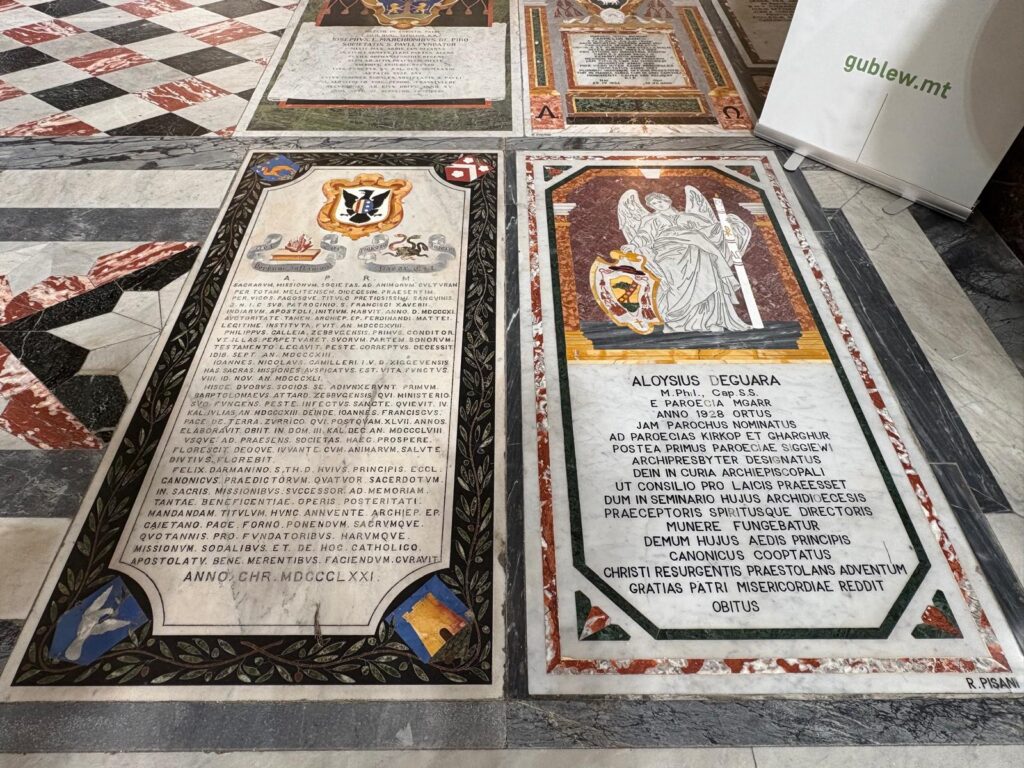

As I was saying above, St Paul’s Cathedral is in the Baroque style. It also has some influences from Maltese architecture. Its main façade is on St Paul’s Square, with two bell towers originally containing six bells. It has an octagonal dome. With the most important Maltese churches, however, it’s not the exterior but the interior that makes the biggest impression. Like St John’s Co-Cathedral (and apparently also the Cathedral of the Assumption in Gozo, which I didn’t visit), the floor of St Paul’s Cathedral consists of tombstones in inlaid marble. They are highly decorative, and very impressive. You can see a few examples in the images above, with common motifs including skulls or skeletons, angels, family crests, and hints at professions, such as bishops’ hats.

The cathedral’s ceiling has frescoes of the life of St Paul by the Sicilian Manno brothers, who also painted the dome that was damaged in the 1856 earthquake. Many of the objects within the church pre-date either the 1856 or the 1693 earthquakes, however. This includes a 15th century Gothic baptismal font, the cathedral’s 16th century main door, and some paintings. There are also later paintings by Mattia Preti, one of Malta’s most famous artists (although born in the Kingdom of Naples). The altarpiece, showing the conversion of St Paul, is his work.

If you only have the time or the appetite for one major church while you’re in Malta, I would probably advise St John’s Co-Cathedral. The style between St John’s and St Paul’s Cathedrals is very similar, with St John’s Co-Cathedral a little grander. Plus the Co-Cathedral has two Caravaggios, which are worth a look. But it’s also interesting to see how different examples of the style differ. Or don’t: given that Malta had competing religious authorities, visually the seats of these authorities are remarkably similar.

On to the Mdina Cathedral Museum

Alright, we’ve seen about all there is to see in St Paul’s Cathedral. Time now to turn our attention to the Mdina Cathedral Museum. The building itself dates to the early 18th century. Around the 1720s, some medieval housing around the cathedral was demolished to make room for St Paul’s Square, a Bishop’s Palace, and the Seminary. The latter is now the Cathedral Museum. This wasn’t its original home, though. A Cathedral Museum was first established in 1897 in a space nearby. It moved here in 1969.

The former seminary was built between 1733 and 1742, and is probably the work of architect Andrea Belli. I would normally picture a seminary as a fairly austere place, but neither of Malta’s religious authorities were in a very austere mindset back in the 18th century. The building is fairly grand from the outside, and follows the normal layout of a palace at the time, with an airy central courtyard. Some of its rooms are lavishly decorated, particularly the chapel. There are some reminders of the various purposes the building served between its lives as a seminary and a museum. These included being the British military headquarters, a boarding school, and an exhibition space. The British military, in particular, greatly extended the building by adding separate wings.

The museum’s collection is a fairly odd assortment of religious and secular items. Some objects come directly from the cathedral, while others entered its collection at different points over the centuries. Together, however, they paint a vivid picture of aspects of history and religious life in this small country.

A Few Highlights

Inside, the museum is split into different areas by object type. There are decorative objects including silverware and wax sculptures, and paintings. One room houses a collection of melitensia, meaning objects from or relating to Malta (you can see Melite, the Roman name for Malta and Mdina, within the word). The collection was bequeathed by Dr. and Mrs J. Ferrugia, Dr. Ferrugia being an expert in Maltese silverware as well as a GP and politician. The silver includes items linked to Grand Masters Manoel de Vilhena and Jean de la Vallette. There are also many historic views of Malta in watercolour and oil, and Maltese furniture.

I particularly liked seeing a couple of items directly connected to the cathedral we’d just visited. For starters, there is a section of the beautiful 15th century choir stall, restored around 2008. The decoration, in inlaid wood, is exquisite. Malta’s oldest bell is also here. Dating to 1370, it was the work of two Venetian brothers. It hung in the belfry of the old cathedral until 1645, when it was christened and consecrated Petronilla (after St Peter). It survived both major earthquakes, and continued to hang in the belfry of the new cathedral until 2008. At that point its historic importance and fragility outweighed its fulfilment of its original function, and it came inside the museum. That gave me the opportunity to examine its charming effigy of St Paul up close.

I also enjoyed the more decorative of the rooms. By this point in my journey around Malta I was rather getting into Baroque architecture and decoration. Not normally my favourite period, but definitely impressive when done well. And Malta does it well. Some rooms are fairly modest, having started life as dormitories or the like. Others are high Baroque, particularly the chapel. With an octagonal layout, the chapel features paintings by Antoine Favray. It also has a trompe-l’oeil fake dome ceiling. Having missed the one in Victoria, Gozo, I was pleased to have an opportunity to admire another fake dome here. Bishop Alpheran de Bussan, who commissioned the decoration of the chapel, loved it so much that he had his heart buried here.

Going Underground

Our visit to the Mdina Cathedral Museum is not quite complete! Having covered the exhibitions as far as we could tell, we spotted a sign for an underground space. We weren’t aware of this aspect of the museum beforehand, but I for one never give up a chance to poke around a museum’s lesser-known spaces. And so down we went. As an aside this actually ended up being the start of quite an underground day in Malta. There were these vaults, then those of the Wignacourt Museum in nearby Rabat, and we finished the day with a tour of Underground Valletta, a combination of Knights Hospitaller water reservoirs and miserable WWII-era bomb shelters. Always worth having sturdy shoes ready to go in Malta!

But coming back to these tunnels, they are actually the least interesting of the bunch. There are plenty of Roman or early Christian catacombs in Mdina and Rabat, but it seems these spaces were just for storage of wine, or oil, or things like that. There are the remains of a Roman wall, though, so a little bit of archaeological interest. After popping back out in that internal courtyard, we got our bearings and headed off to our next point of interest.

Overall, the Mdina Cathedral Museum is a fairly interesting place. I’m not sure if we would have come here if the ticket didn’t cover both the museum and the cathedral. The collection is at times an odd assortment. One thing I haven’t yet mentioned, which has pride of place, is a collection of Dürer prints. Did I come to this museum expecting to find one of the largest collections of the artist’s prints outside Germany? No. Do I particularly like Dürer’s work? Also a no. But I did appreciate them. It’s remarkable that the collector, Count Saverio Marchese, bequeathed them to the cathedral as long ago as the mid 16th century. And that they have remained in the cathedral’s collection all that time.

And that was the main thing I took from St Paul’s Cathedral and its museum: a feeling of continuity and tradition within Malta despite upheavals like earthquakes or changes of ruler. It contrasts well with Valletta’s history, wrapped up as it is with the Order of St John.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.