The Inquisitor’s Palace (Il-Palazz tal-Inkwiżitur), Birgu (Vittoriosa)

The only Inquisitor’s Palace in the world that’s open to the public? How could I not stop by for a visit?

A Final Stop in and around Valletta

We have been busy over the past few days! I wrote a post introducing Malta and exploring some of the options for culture lovers. We then did a deep dive into Valletta, Floriana and the Three Cities, before looking at some of the specific sites within each. My last post was a heritage walk around Floriana. And now today’s post is a final stop in this part of Malta. And a very interesting one at that.

I’d first noticed an Inquisitor’s Palace when looking at Google Maps. Hmm, I thought. I’ve never been to one of those before! And the reason for that became apparent as I learned more. Because it is, according to several sources, the only remaining Inquisitor’s Palace in the world that you can visit. So says this Inquisitor’s Palace’s Wikipedia page. But in the same breath (or on the same page at least), it links to one in Mexico that is a Museum of Mexican Medicine. So there’s probably some kind of technicality I’m missing.

But anyway, it’s a rarity. So I had it on my list as somewhere I might want to visit in the Three Cities. We spent a nice afternoon there, travelling over by dgħajsa (a traditional boat), wandering up to Fort St Angelo, then back to Birgu’s* Old Town. After a stroll around there looking for auberges**, guess where we found ourselves? Yes, in front of the Inquisitor’s Palace. How handy. And so we stopped in for a look.

*If you’ve been reading my previous posts, you’ll know that the Three Cities (and many other places and things in Malta) have more than one name. Birgu is also called Vittoriosa.

**Again, if you’ve been reading my posts, you’ll remember these are the headquarters of different national groups of the Knights Hospitaller.

Different Inquisitions

“Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.” But did you know that there were multiple inquisitions? I did not, although the clue is in the name – if there was only one Inquisition, it wouldn’t need to be designated as Spanish!

Inquisitions got their start in medieval France. With Cathars and Waldensians spreading their unorthodox beliefs, a judicial procedure to investigate heresy, apostasy, blasphemy, witchcraft, and other suspect customs seemed like a good plan. Early on it was mostly local clergy presiding, but later the power to determine who was orthodox in their beliefs and who was not shifted to the Dominican order. Inquisitions later spread to other countries, including Spain, of course, and Portugal, as well as their empires: Goa, Mexico, Peru and so on. They did not technically have authority over non-Christians, but did over Christian converts suspected to not really be as converted as they claimed. They based their methods on Roman law, and used quite a bit of torture, unfortunately.

The Inquisition to which this Inquisitor’s Palace belonged was the Roman Inquisition. This one started in the second half of the 16th century, and oversaw the judicial process across the Papal States. I suppose this applied to Malta because the Knights Hospitaller are a religious order, tied at one time to the Holy Roman Empire. The Roman Inquisition is also the only one to still exist, albeit in another guise. It’s part of the Roman Curia (which in our last post we learned means an administrative function for a part of the Catholic church) and is now called the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith.

The Roman Inquisition in Malta

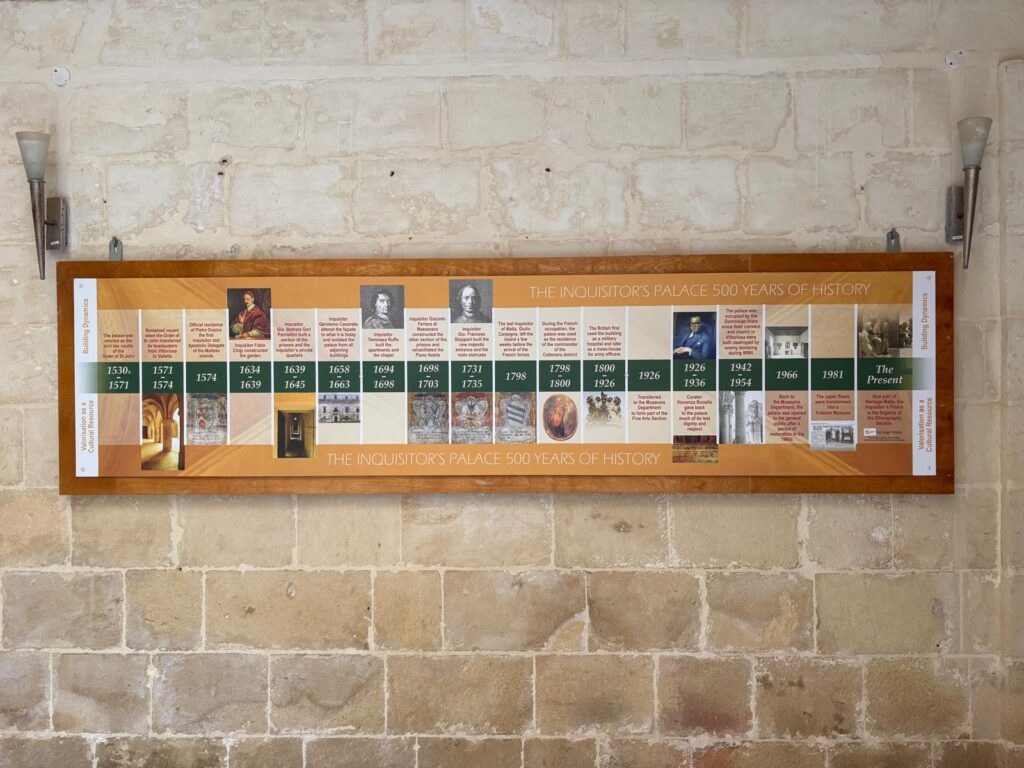

The Inquisitor’s Palace got its start as a courthouse in the early 16th century. The Magna Curia Castellania Melitensis was known as the Castellania for short. It was here in Birgu until 1572, when it moved, along with the Order of St John generally, to Valletta.

The Roman Inquisition arrived in Malta in 1574, 30 years after its founding. The first Inquisitor was Pietro Dusina. Grand Master Jean de la Cassière offered Dusina the Castellania as his official residence. Dusina accepted, and turned it into an early live/work space, with space for tribunals and a prison as well as acting as his palace.

Various Inquisitors over the years made substantial changes to the building, so much so that there’s barely a trace of the earlier courthouse (just a small courtyard and cloister). The palace absorbed neighbouring properties over the years. Earthquakes were another reason for changes and rebuilding. Eventually, it took on the appearance of a Roman palazzo, with Baroque influences.

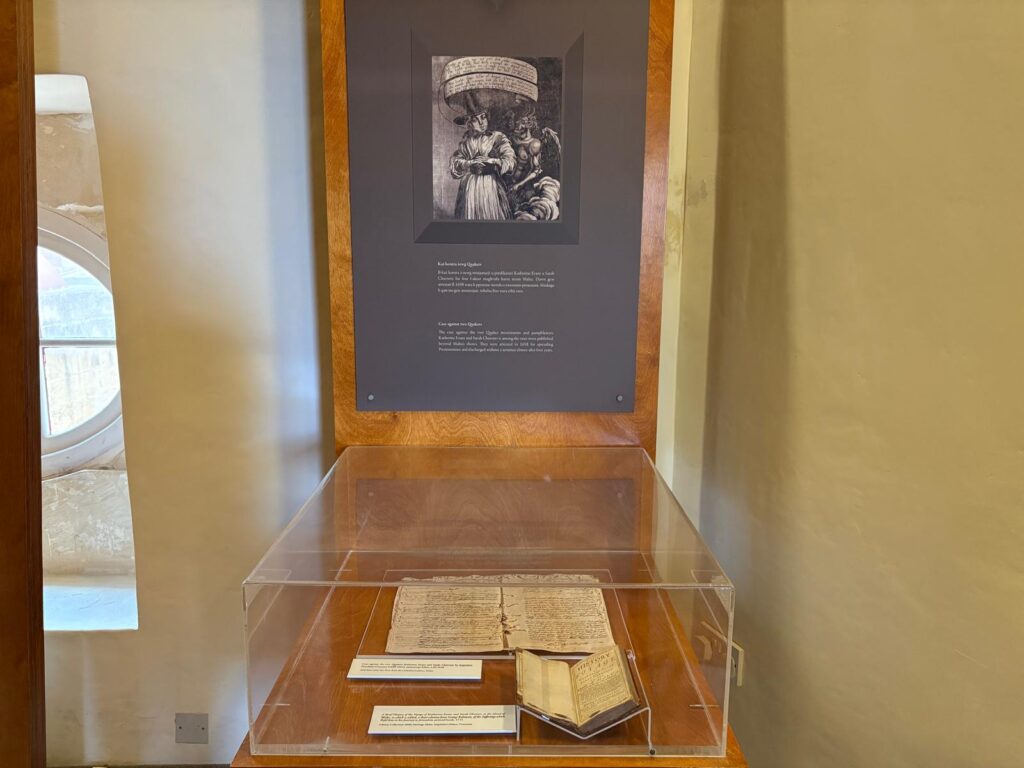

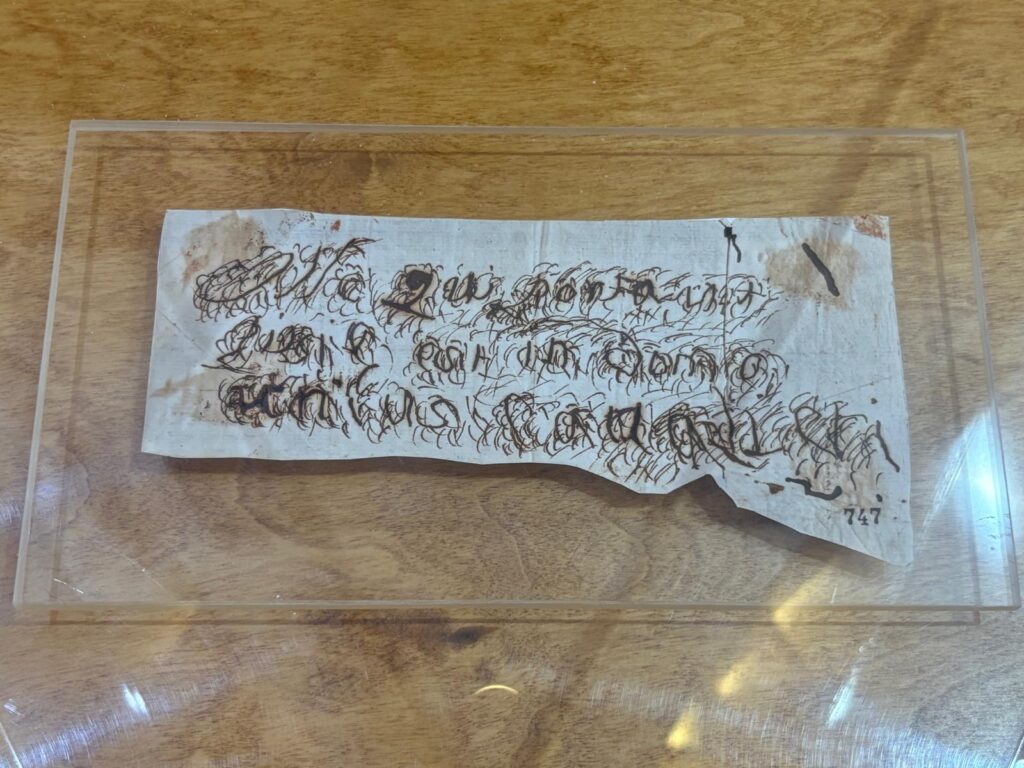

The Roman Inquisition was kept fairly busy in Malta. A lot of their work seems to have been small-scale accusations of witchcraft (commonly love spells) and use of the evil eye. In the mid-17th century two English Quaker women were imprisoned for three years for proselytising before being released due to political pressure. Caravaggio, who was briefly a Knight of the Order of St John to avoid separate legal problems, testified in front of the Inquisition in 1607 in the trial of a Greek artist accused of bigamy.

The Inquisition came to an abrupt end in Malta in 1798, with the arrival of Revolutionary French forces, who were of course atheists and didn’t go in for that sort of thing. The building was first used as the local district headquarters, and later for various purposes including a military hospital and then mess house for British officers.

Part Accusations and Torture, Part Ethnographic Museum

By the 20th century, the palace was in rough condition. It was now the property of the civil authorities, who made plans to demolish it. Luckily, this didn’t happen. It transferred to the Museums Department in 1926, and extensive renovations began. These had only just finished before the outbreak of WWII, and in 1942 the building took on a religious function once more, temporarily, as a convent for Dominican friars made homeless by aerial bombardments. It transferred back to the Museums Department in 1954.

The Inquisitor’s Palace finally opened as a museum in 1966. In 1981, the top floor became a Folklore Museum. It went through another cycle of decline and restoration in the 1980s, reopening as the National Museum of Ethnography in 1992.

It still fulfils this dual function today. There are exhibits relating to the Inquisition, but the palace is also home to Heritage Malta’s ethnography section. It’s a sort of historic house and museum combined. The ethnographic sections attempt to tell the story of how the Inquisition impacted everyday life in Malta, but I think this is a bit of a stretch. I saw the two elements more as existing alongside each other. Sometimes quite literally – some rooms have a combination of period furniture or furnishings, and ethnographic exhibits on festivals or other topics.

A Few Highlights

The dual function of the Inquisitor’s Palace as a museum makes it an interesting place to visit. There are quite a number of different areas making up the visitor experience, with a more or less coherent path between them. It starts with an introductory video, before you head to the historic kitchens. Then it’s upstairs to the piano nobile, or main rooms, over a couple of floors. This is where the ethnographic collection and the story of the building as a palace combine.

The area I found most interesting was that which told the story of the tribunals held here. This part has been brought up to museological standards more recently than the rest of the museum. There are few objects which directly tell the story, but some archival materials on view. Personal stories are used where possible to bring the work of the Inquisition to life. This includes those two Quaker women, Katherine Evans and Sarah Cheevers. There’s also a bit about Caravaggio’s testimony. This section does a good job of explaining to a modern audience what it was like to be subject to religious authorities in all aspects of life, in a way not common now in Christian countries.

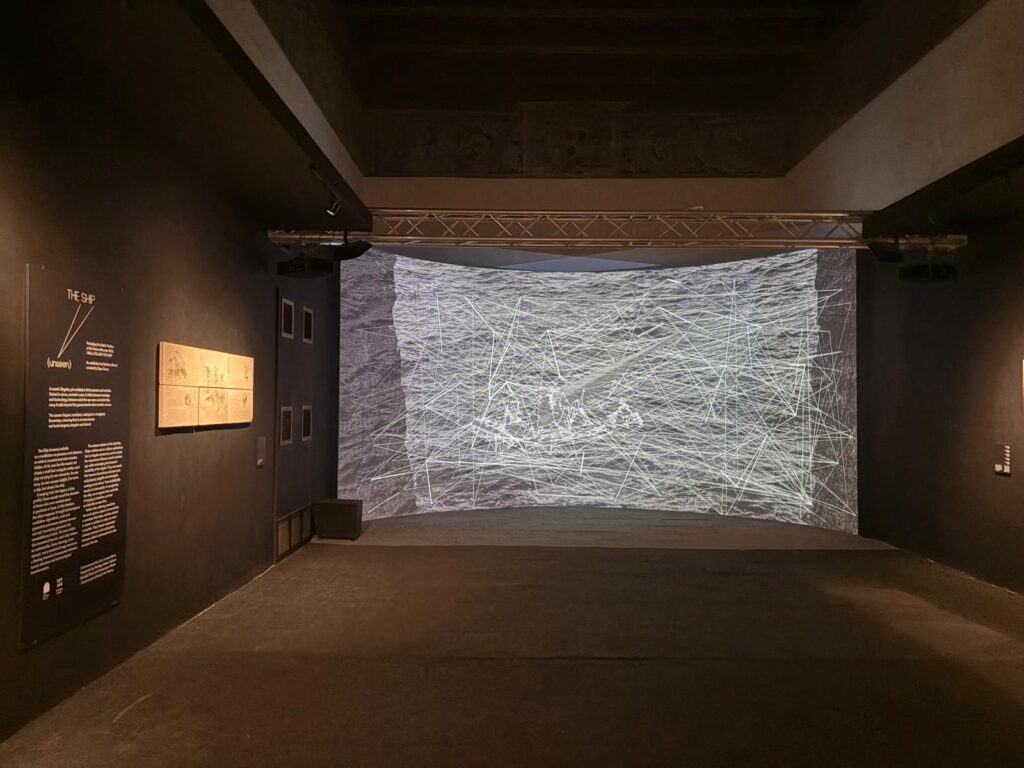

There are some other sections still to go. Within the section on tribunals there is a temporary exhibition space. When I visited, it hosted The Ship (Unseen) by Matthew Attard, a continuation of Malta’s 2024 pavilion at the Venice Biennale. I found it a little incongruous, but not as much as a display of hats in another temporary exhibition space elsewhere. To finish with, visitors pass through the palace’s prison cells. By this time you’ve seen a video on torture methods, so can imagine the misery of the inmates. And with that, we headed back to the exit and out into the sunshine, glad not to have run into the Inquisition itself.

Final Thoughts

In the end, the Inquisitor’s Palace wasn’t quite what I had expected. I didn’t know before visiting that it doubled as the National Ethnographic Museum. And so wandering around learning about Inquisitors and Maltese Christmas traditions at the same time was a test for my brain’s elasticity.

If I’m honest, though, I retained very little information on the ethnographic collections. I think I would have absorbed it better if it were in its own space. Plus, these days, calling it an ethnographic museum doesn’t (for me) quite fit the bill. Malta is no longer anyone’s colony or territory, it’s an independent nation. So the idea of othering inherent in an ethnographic museum seems outdated. I think there’s a gap in terms of good names in English for this kind of institution. Something like a Musée d’Art et Traditions Populaires, as we saw in Olargues, works a bit better.

But this is in some ways ignoring the practicalities. The road for the Inquisitor’s Palace to become, and stay, a museum has clearly been a tricky one. It’s a big space to maintain, and presumably needs as many visitors as possible to keep going. And, coming back to one of the first points in this post, it’s a very unique space and worth preserving for the public. The Inquisitions in all their forms were once formidable institutions, with the power of life or death over great swathes of the population in Europe and beyond. That story deserve to be told.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.