The Wignacourt Museum, Rabat

Our final stop in Malta, the Wignacourt Museum includes art, objects, extensive tunnels, a church, and a site of Christian pilgrimage.

A Final Stop in Malta

The time has come for us to bid farewell to Malta. My trip there was a memorable one, and absolutely packed with cultural highlights. We learned about the history of the Knights Hospitaller in Valletta, Birgu and Floriana, and took a trip to Gozo. We’ve seen forts, archaeological museums, and palaces belonging to Grand Masters and Inquisitors. On a daytrip to Mdina and Rabat we’ve so far stopped in at St Paul’s Cathedral and Mdina Cathedral Museum and, my personal favourite, the Palazzo Falson. All that remains for me after today’s post is to share with you an overview of Malta’s Neolithic sites and their history.

But let’s not rush off to that final post before we’re ready. Because today’s subject, the Wignacourt Museum, needs due care and attention. This was another place I’d spotted in advance, and had a fair idea I wanted to see despite not having a fixed itinerary for the day. My guidebook described a “charming old palazzo” that combined a varied collection with underground catacombs and bomb shelters. An interesting blend indeed.

And so, once we’d finished in Mdina, we more or less made a beeline through Rabat towards the Wignacourt Museum. Rabat itself was a real contrast to the narrow streets of Mdina. It feels a lot more open, more lived in. Almost as historic, though, as we’re about to discover.

St Paul and his Grotto

Let’s start at the beginning. This museum ultimately exists because St Paul’s Grotto exists. But what was St Paul doing in Malta, and what is this about a grotto?

If you read the Salterton Arts Review assiduously, you’ll know the broad strokes already. It all started with a shipwreck. Or, actually, taking a step further back, it started with St Paul being arrested in Jerusalem, and transported to Rome to face trial. On the way, there was a shipwreck. Tradition has it that St Paul came ashore in Malta, and made his way to Melite (now Mdina and parts of Rabat). He stayed there for three months, living in a grotto. During this time he met the local leader, Publius, and performed miracles which convinced Publius to convert to Christianity. Publius was later a bishop, and eventually St Publius, Malta’s first Catholic saint. St Paul’s influence helped to spread Christianity throughout Malta’s population.

I’m not entirely sure why St Paul would have stayed in a grotto during his Maltese sojourn, but I guess you don’t normally come away from a shipwreck with a lot of funds. Plus early Christians often had quite an ascetic bent. But the sum total of all this is that there is a grotto, in Rabat, which is reputedly that in which St Paul resided. I don’t think anything much was happening there for a long time. Presumably some visitors and pilgrims, but nothing formal. That was to change in the 16th century.

A Grotto Becomes a Site of Pilgrimage Becomes a Museum

The change in the 16th century was that someone took a real interest in the grotto. That someone was Don Juan Benegas de Cordoba, which to me sounds like rather a grand name for a hermit. But a hermit he was, who visited and took up residence in the grotto, thus starting to popularise a cult of St Paul in Malta. Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt could see the possibilities, and in 1617 assumed guardianship of the grotto. St Paul was after all one of the patrons of the Order, along with St John.

Wignacourt set up a college with chaplains to care for the grotto, and made Benegas its rector. This raised the status of the church above the grotto to that of a collegiate church. I’m a little confused about the churches, actually. But I think the situation is that there is a Church of St Paul and a Church of St Publius. The former has been around since at least medieval times, although the current building is the work of Maltese architect Lorenzo Gafà and built between 1653 and 1683. Our friend Benegas apparently ordered the construction of the Church of St Publius annexed to the Church of St Paul, and through which one enters the grotto. The current version of that church dates to 1726. You can see why I’m a bit confused.

Anyway, the churches and their college continued on through the 17th and most of the 18th centuries. In 1798, under French rule, the church continued to use the college, but now under governmental administration. It was in the 20th century that its use changed: to a school, an infirmary, and a social centre. It then returned to the church in 1961, before opening as a museum in 1981. The museum displayed objects and artworks from the college, the two churches (and some others), and donations from private individuals. The core of the art collection, for instance, is a donation by notary Francesco Catania.

A Museum Complex / A Complex Museum

And so after piecing together that bit of history, we can see where today’s rather unusual museum comes from. And there’s even more history where that came from. As visitor experiences go, it makes things a little peculiar. You arrive through the 1749 college building. It’s Baroque, as are so many of Malta’s notable buildings (if it ain’t Neolithic, it’s Baroque!), and on three floors. A small ticket desk stands in front of you.

Ticket in hand, you now have a choice. Left to the grotto, catacombs and WWII shelters, or right to the museum-y part of the Wignacourt Museum? We went left, partly because I really wanted to see St Paul’s Grotto. So we wended our way there first. I saw the grotto and a few other underground spaces, then headed up the staircase to see what was above us. A church! The Church of St Publius (I believe). Now you can see the function of the church as a protector standing over the grotto and leading down into this sacred space. The current visitor experience is a little backwards. And a church that you can only enter from its basement seems a little odd somehow.

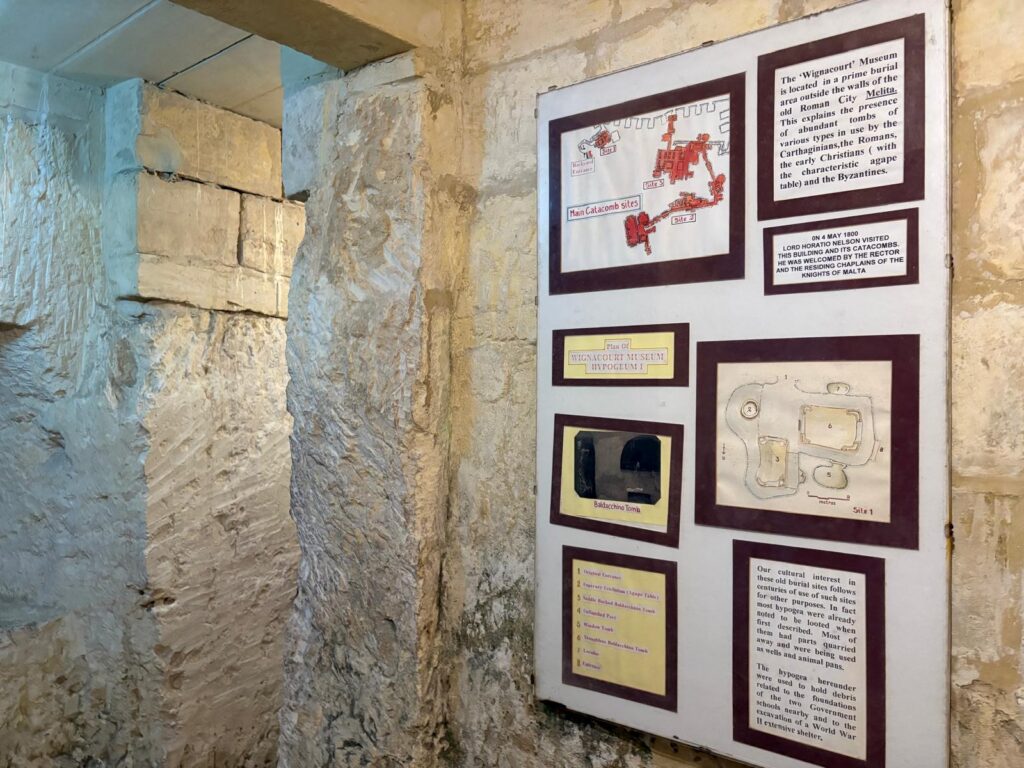

We then went back down the stairs, retraced our steps, and proceeded to the catacombs and tunnels. Malta has a lot of underground spaces to visit. In Rabat alone, as well as the Wignacourt Museum, there are St Paul’s Catacombs and St Agatha’s Catacombs. The space in the Wignacourt Museum tells a couple of very different stories. The older parts are Punic, Roman and early Christian burial spaces, or hypogea. Underground burial was common in Malta from Neolithic times, even though there was no continuity in population or belief system between those early inhabitants and the builders of the spaces we’re now visiting. There are a lot of tunnels and chambers to see, as well as one or two ritual spaces.

But some of the tunnels look decidedly newer. Those are WWII-era bomb shelters. Malta was very hard hit by bombing, and shelters were critical to protecting the population. These tunnels had about 50 rooms, sheltering around 350 people. We also went to Underground Valletta during our stay, another site of mixed WWII and older underground spaces. The residents here in Rabat were comparatively comfortable compared to those damp and miserable tunnels.

Upwards to the Museum!

We’ve seen the below-ground Wignacourt Museum now, let’s head back to the ticket desk and turn right for the museum itself. If, like me, you’ve already been to the Mdina Cathedral Museum over yonder, the Wignacourt Museum might feel a little similar. Both are the collections of religious institutions at their core, augmented over the years by donations and other acquisitions.

Let’s start with the notary I mentioned, Francesco Catania, whose bequest makes up about a third of the collection. And that’s despite the bulk of what he left to St Paul’s Collegiate Church being auctioned off after his death in 1962. Like Olof Gollcher, Catania was a collector of broad interests. The museum displays paintings, prints, maps, archaeological artefacts, coins, melitensia (meaning objects from or related to Malta), and artworks produced by Catania himself. There are some good examples of Baroque painters we’ve encountered before, like Antoine Favray and Mattia Preti.

Branching out from Catania’s collection, the Wignacourt Museum has more of the same, as well as a number of interesting curiosities. A 17th century death mask, for instance; a copper bathtub; and a portable altar such as were used on the galleys of the Order of St John. There are a number of reliquaries, and even a replica of the Shroud of Turin. It’s the type of museum where you never quite know what’s around the corner.

Final Thoughts on the Wignacourt Museum

Even more than the curiosities in the collection, I liked the presentation of the Wignacourt Museum. The upstairs, where visits begin, is a fairly standard museum, and is where most of the art is. The downstairs is much more idiosyncratic. A series of rooms comes off a corridor to one side of a courtyard. They are a mixed bag. Some are ordinary, one has a hidden shrine of some sort. As you move further down the corridor, it’s like the museum is losing steam and reverting back to being a religious building. One or two rooms contain pleasant jumbles of objects, like store rooms for infrequent festivals.

Just when you think you’re done, there’s a door to a further outdoor space. You test it: can I go through there? Yes, I can! The main attraction in this courtyard is a large anchor: a replica of a Roman one. The lead part of the anchor was discovered in 2005, inscribed with the names of Egyptian deities Isis and Serapis. The replica shows what it would have looked like with the wooden parts of the anchor intact. Let’s continue. What is this, in about the last room of the museum? A car? Yes: it’s the archbishop’s car. Or was. An Austin Six Limousine dating to 1937.

In the corner of that room is one of the blind exits that seemed mysterious back at the start of our journey, in the underground catacombs and tunnels. I wasn’t quite sure why I could climb a staircase and get a glimpse of a room, but not enter it. Now it feels like a full circle moment. I wouldn’t say the Wignacourt Museum makes a lot of sense to me, even now. But I liked it. It’s charming, has genuinely interesting displays, and is a generous museum, too. Three for the price of one, by the time you count the grotto, the tunnels, and the museum itself. The uniqueness of the site, and the different historic elements and periods all abutting each other, seem like Malta in a nutshell.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.