Ithell Colquhoun – Tate Britain, London

Ithell Colquhoun offers a compelling introduction to a quietly radical Surrealist who merged nature and the occult into a singular artistic vision.

Getting Value from that Two-for-One Ticket

Recently on the blog, I wrote about Tate Britain’s exhibition Edward Burra. It was, I said, very refreshing to have the enormous Tate Britain temporary exhibition space split into two, each half with a separate exhibition. There’s no attempt to link the two, directly or indirectly.* They are physically proximate but each stands on its own merits.

There are two immediate benefits to this. The first is that each exhibition is still a decent size, without being completely overwhelming. Previously, I would often round a corner in this exhibition space and despair that the end was not yet in sight. Not a good frame of mind to take in artworks and artists. The second is that the exhibitions are being sold as a two-for-one. You get one ticket to both, and choose which order to see them in. And if you fancy a spot of lunch in between, or a trip around the permanent collection, well that is your prerogative.

I’ve posted these reviews in the order in which I saw the exhibitions. Edward Burra first, followed by Ithell Colquhoun. The latter has already had a stint at Tate St Ives, and it sounds from what I’ve read like there are some minor differences between the two. But let’s crack on and see what it’s all about, shall we?

*In researching ahead of posting these reviews, I learned of an interesting link: the Tate holds the archives of both artists. That would actually be an interesting thing to have surfaced. Do they hold many artists’ archives? How did the archives end up with them? Or am I just being a nerdy historian now?

Ithell Colquoun: An Artist in Search of the Invisible

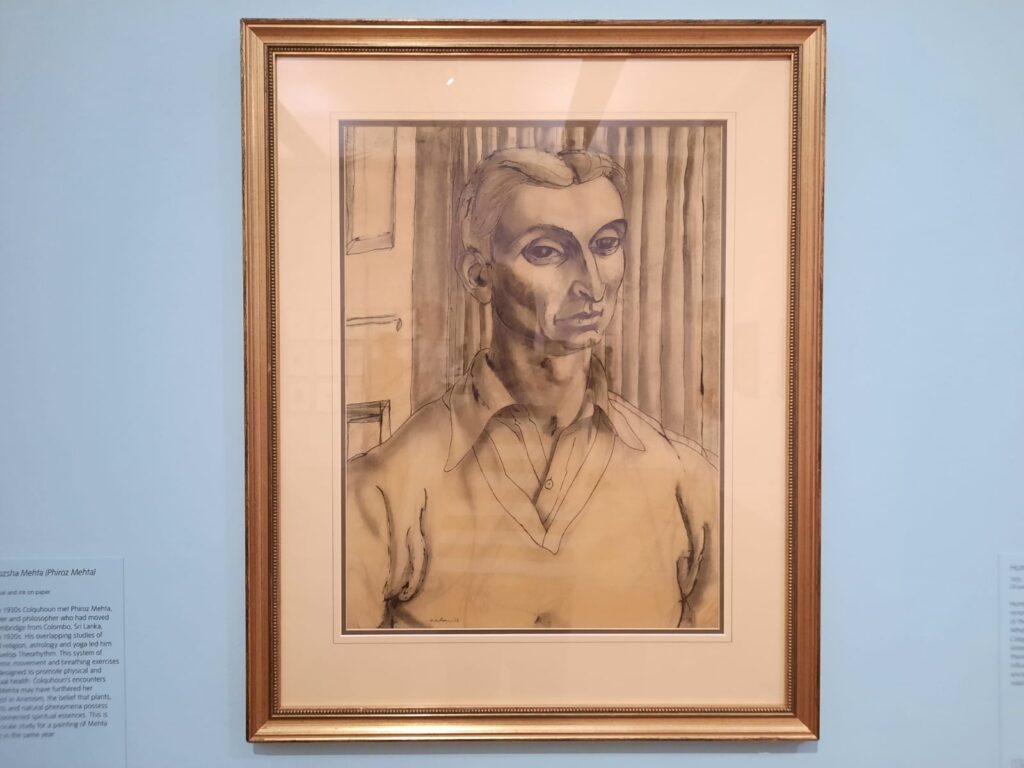

Ithell Colquhoun remains an intriguing figure on the fringes of 20th-century British art, as an artist who was both connected and followed her own path. Born in 1906 in colonial India, she studied at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and the Slade School of Art, and began to develop her interest in the mystical alongside her artistic training. In the late 1930s, she briefly joined the British Surrealists, but was expelled in 1940 when she refused to abandon her interest in occultism (a condition of membership). Between this and the story of Claude Cahun in this recent play, Surrealists are really starting to sound a bit tiring in their treatment of female members… Anyway, rather than acquiescing she doubled down, weaving spiritual symbolism into her practice.

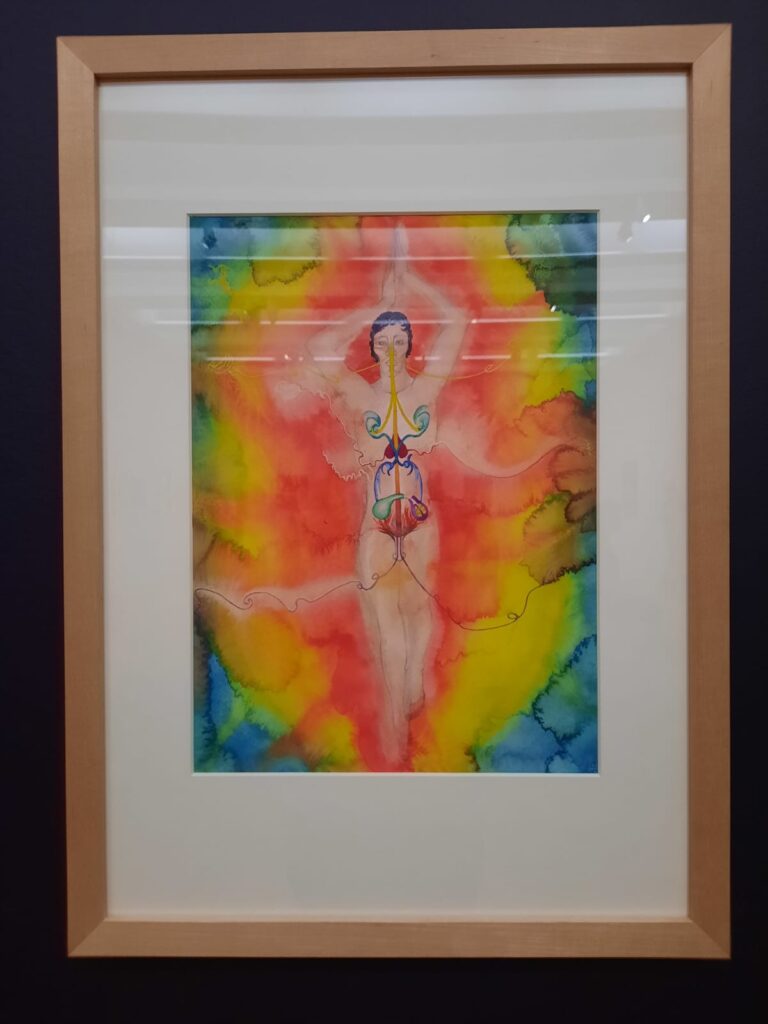

Colquhoun’s lifelong fascination with the esoteric encompassed everything from alchemy and Druidic myth to automatic writing and tarot. That breadth is visible here, in a body of work that crosses media and tones. There are echoes of Hilma af Klint in her insistence on art as a means of gaining metaphysical insight, and in her relative indifference to artistic celebrity. Colquhoun preferred private, intuitive exploration over public recognition. This might explain why she remained somewhat peripheral for much of her lifetime.

And yet the quality and ambition of her work largely speak for themselves. Colquhoun moved easily between careful figuration and experimental abstraction, unafraid to take risks. Like af Klint, slowly but surely, Colquhoun is emerging not just as a fascinating outlier, but as a serious artist in her own right. This exhibition of course forms part of that late recognition.

Colquhoun’s Visual Language

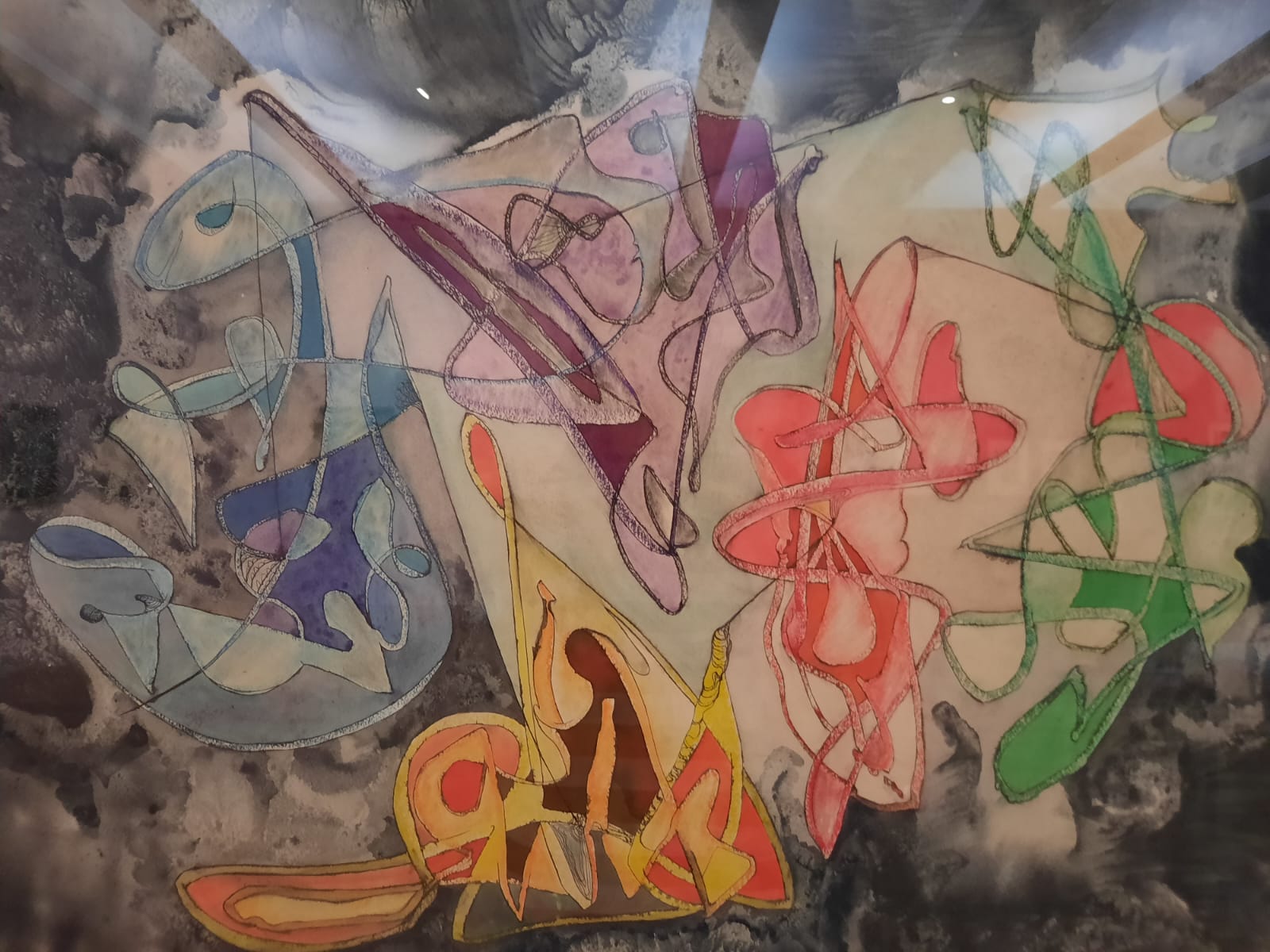

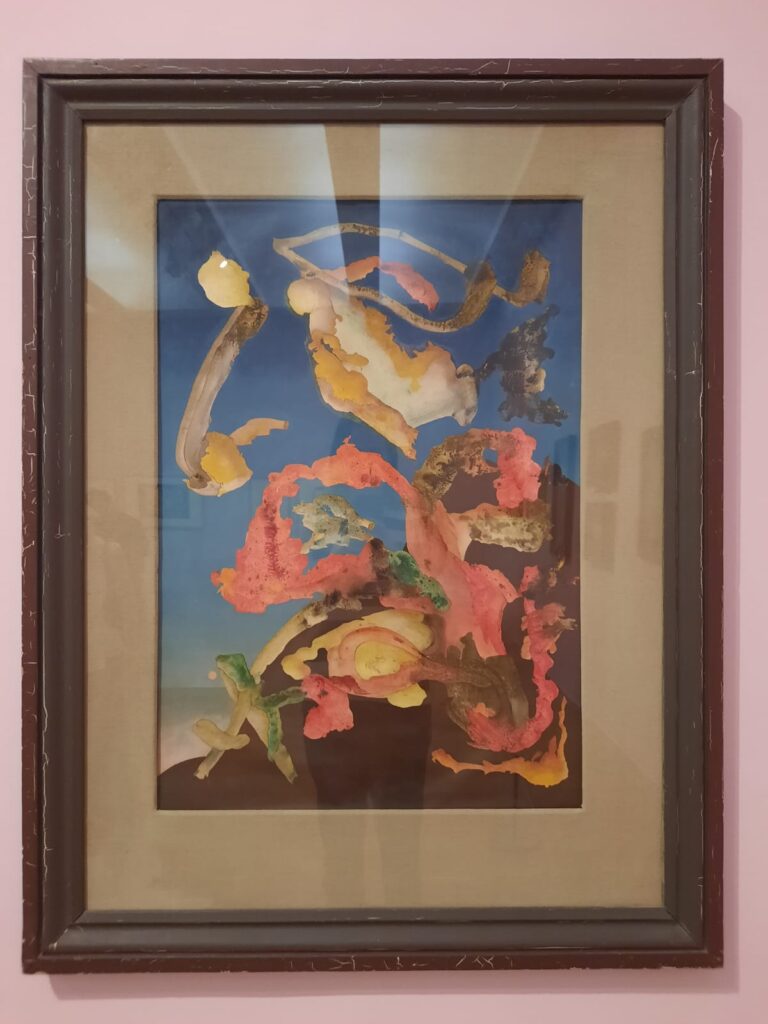

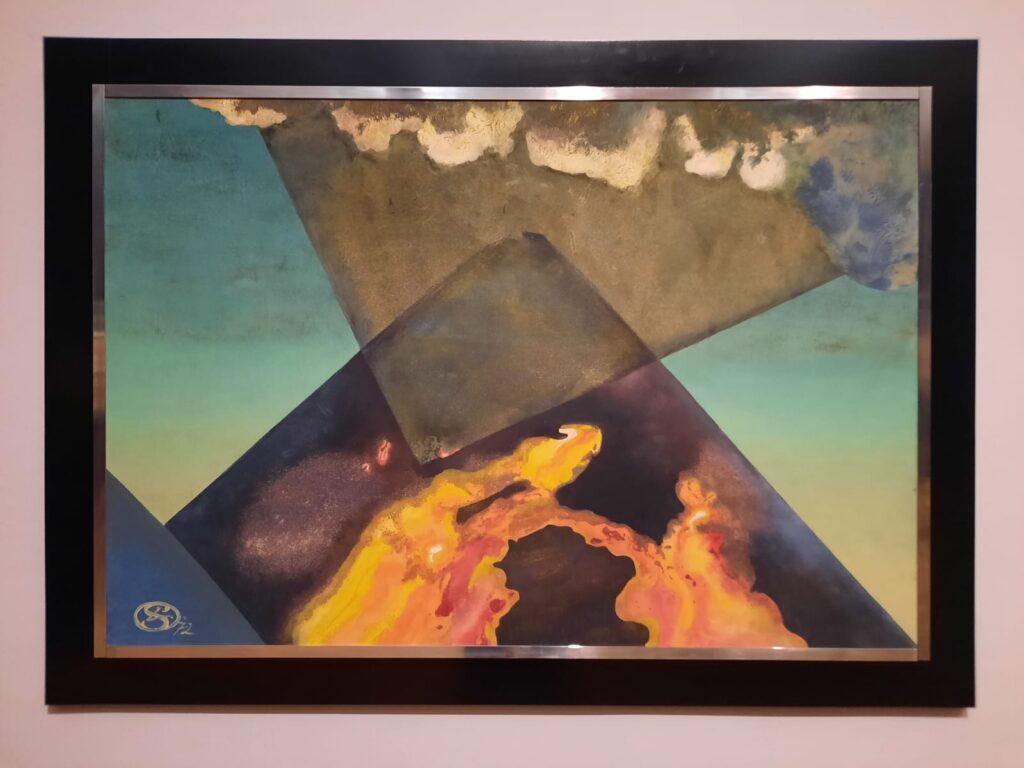

Ithell Colquhoun’s visual language is at its most potent when it crosses boundaries between myth, mind, and landscape. Early rooms display figurative works: frequently unsettling compositions that merge biblical or mythic figures with uncanny plant forms. These are followed by her experimental mid-century techniques in automatism, including fumage (creating accidental patterns with smoke), decalcomania (a fancy version of a child’s butterfly painting), and parsemage (invented by Colquhoun: uses powdered chalk, charcoal and water to create accidental images). The organic randomness of these techniques allows the artist freedom while ultimately retaining compositional control.

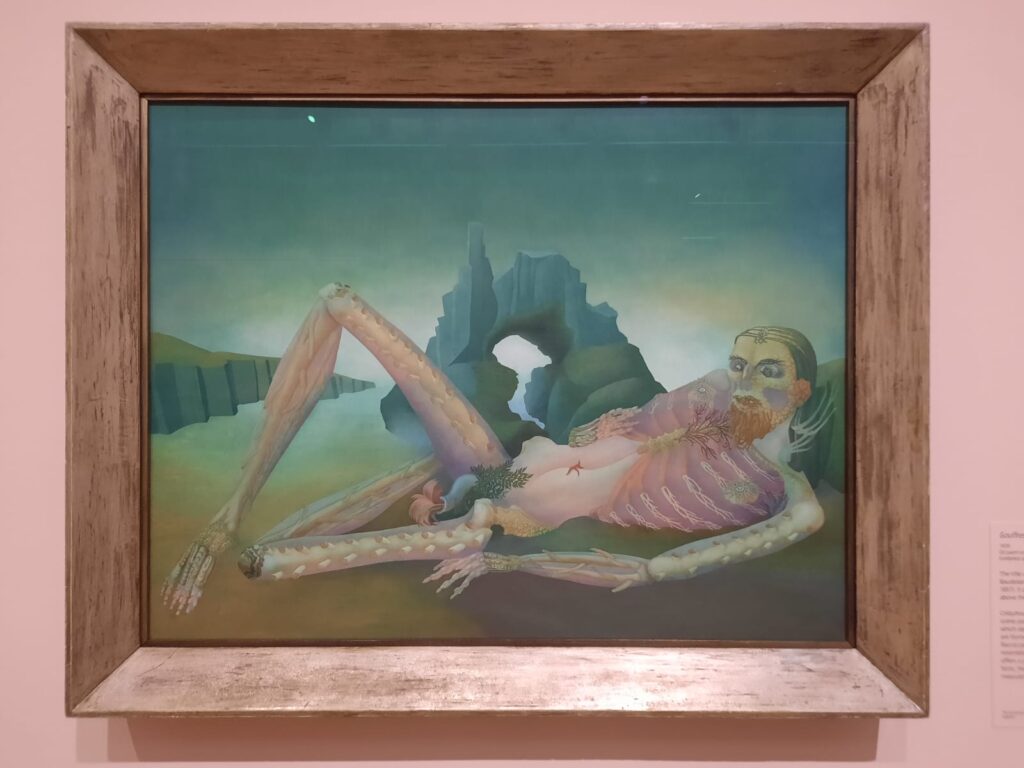

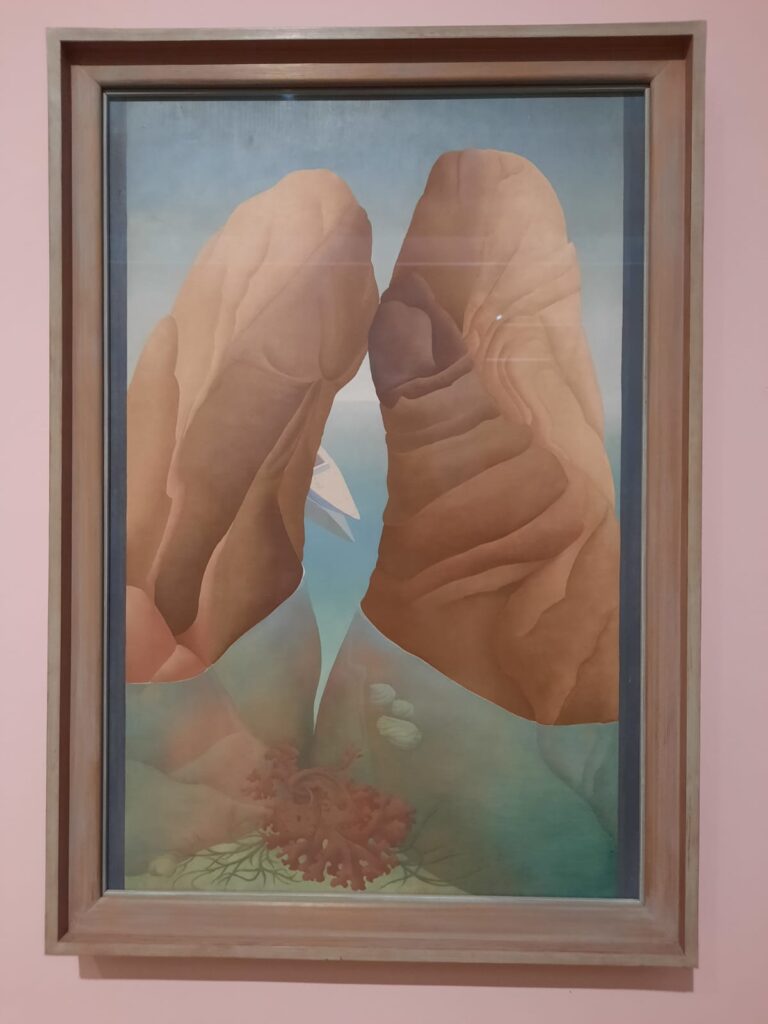

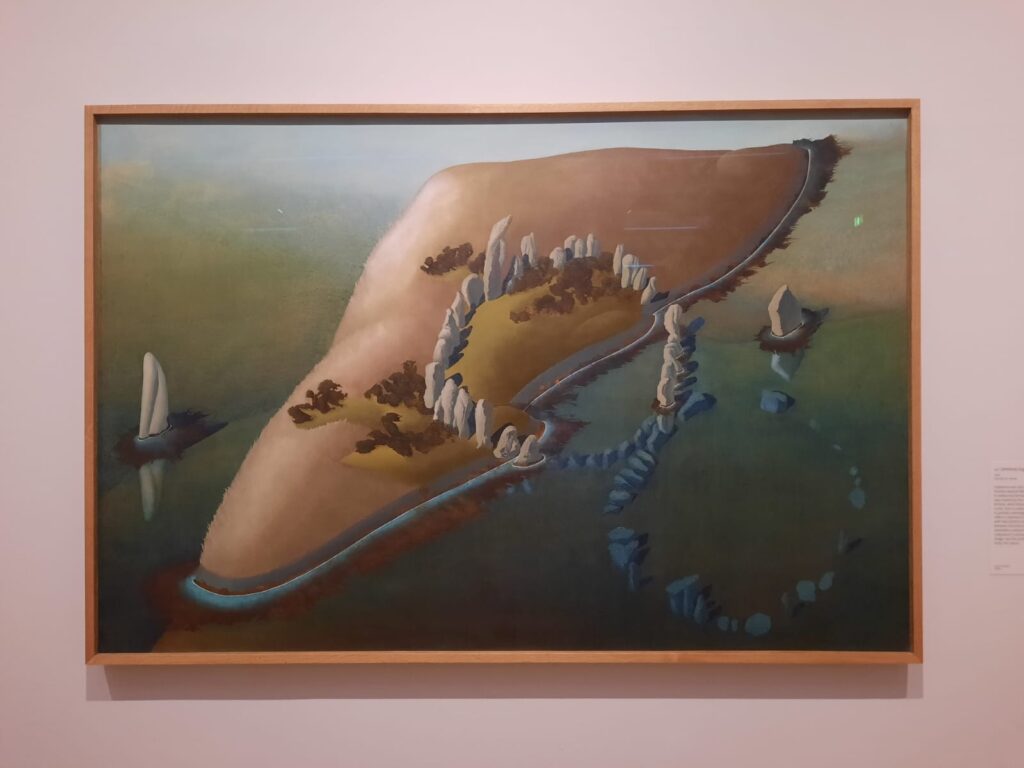

Certain works invite prolonged study. Scylla, for instance, appears at first glance to be looming rocks against deep water. Step back, and you are unmistakably looking at the shape of a woman’s submerged thighs. Danger and seduction intertwined. It’s a clever visual pun, disguised as naturalism. In other pieces, human forms sprout into flora, or branches morph into veins: subtle reminders that the human, the natural world, and the symbolic are all intertwined. There’s an almost mediumistic edge at times, as if Colquhoun were channeling visions from another realm into paint.

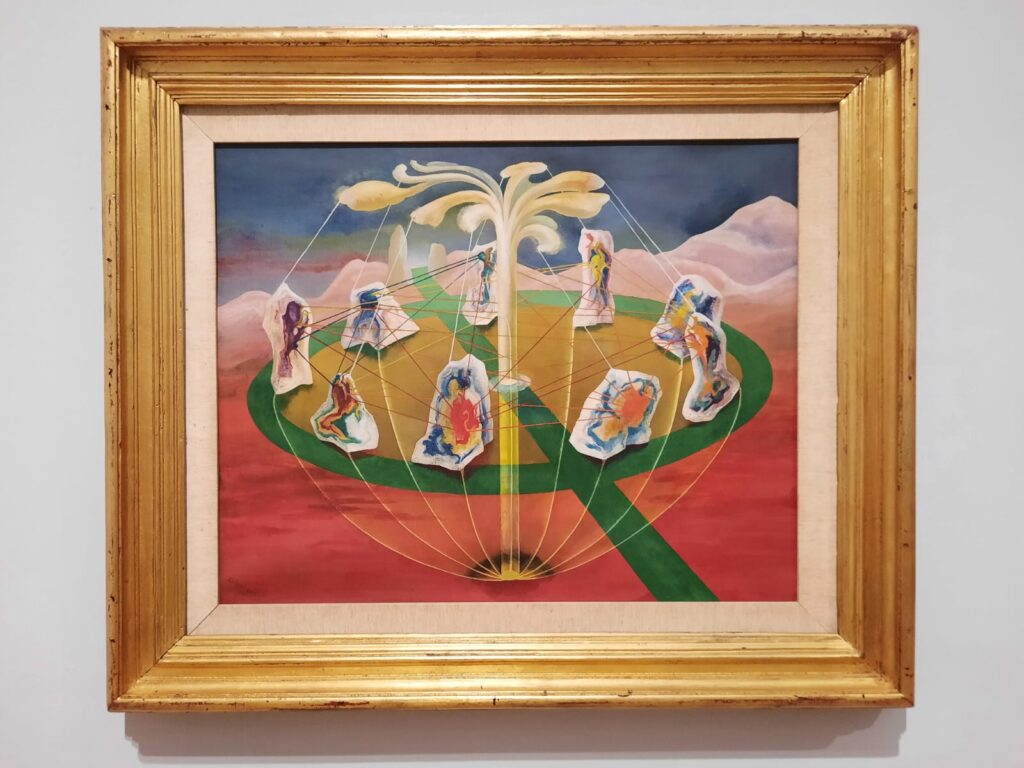

Her later tarot designs and cosmic abstractions start to get more speculative than observational. Mandalas and astral maps for the occult-minded. They reinforce the sense that Colquhoun’s art was never just surface decoration. It’s an attempt to make visible the invisible forces at work in the world. This makes for an interesting art exhibition. Because everywhere you look, the artist’s message is that this isn’t just art, it’s an invitation into a liminal world between the natural and supernatural.

The Art of Curation

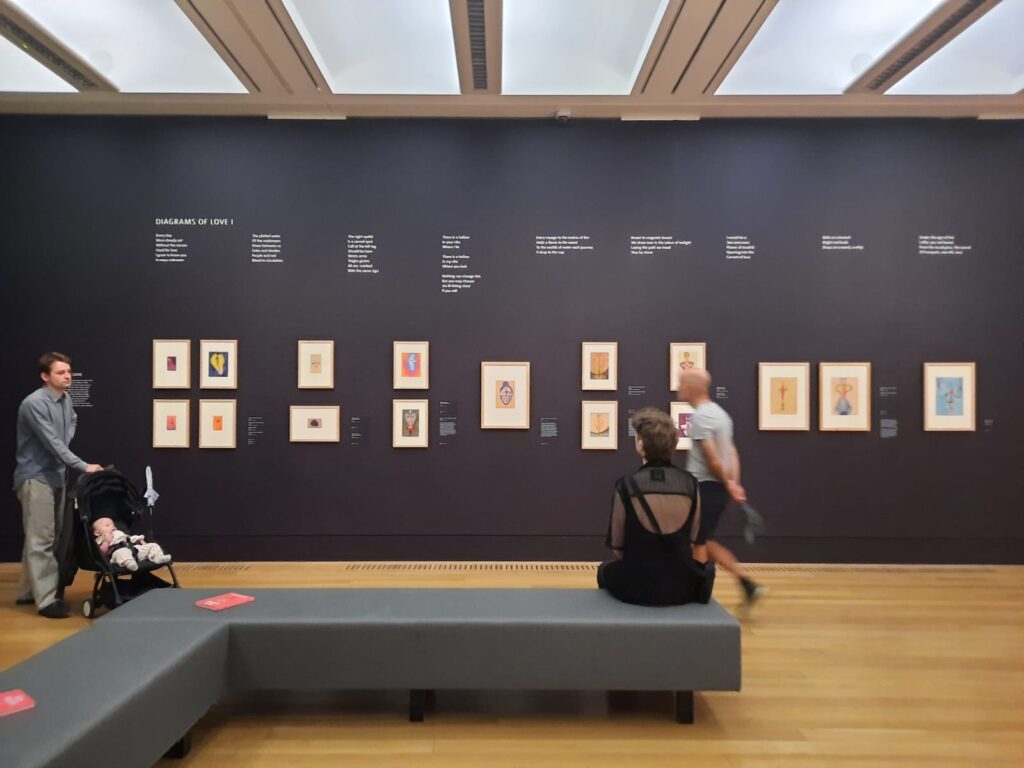

Unlike Edward Burra, the exhibition’s curators have chosen not to fit Colquhoun’s work into a tidy, linear narrative. The exhibition is loosely chronological (early figurative paintings, surreal experiments, wartime tarot work, later abstraction) but it’s also carefully thematic. Rooms are arranged to emphasise the overlap between femininity, nature, myth, and the occult. The result is atmospheric.

Yet the relative lack of context leaves some questions hanging. And, a similarity with the neighbouring exhibition, we know little of her personal life, politics, or why spiritual matters held such importance. From what I’ve read, Tate St Ives and Tate Britain have each given the exhibition a slightly different focus. The Tate St Ives version sounds like it dealt more with Colquhoun’s complexity. Here the scale is a little increased (I believe), so perhaps a little more diluted as a result. The end result is that we experience the emotions of Ithell Colquhoun’s work, but never seem to glimpse the woman behind it.

I intended not to make so many comparisons but here I go again: I liked the soundtrack in Edward Burra, and perhaps something similar here would have offset the occasional dryness of chronology. But despite these small gaps, the exhibition is a nice opportunity for reflection and introspection.

Final Thoughts

We may not fully decode Colquhoun’s metaphysical strangeness, but the exhibition is absorbing. Ultimately I think that’s its greatest strength. It’s art that encourages contemplation rather than commodification. As a relatively obscure mid-century Surrealist with deep spiritual inclinations, Ithell Colquhoun doesn’t need a sprawling retrospective. Instead, this tight, richly curated show provides an excellent introduction. It retains mystery and invites curiosity, while refusing to explain away her complexity.

It’s also a feat of curation, bringing works together from different sources (which long-time readers know I love). If future shows unpack her life or explore her occult leanings more explicitly, that could be exciting. But this version works well as it stands: an evocative, and richly textured window onto an artist who has long existed between worlds, public and private, material and mystical.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Ithell Colquhoun on until 19 October 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.