Wimbledon Windmill Museum, London

A decade after living nearby and never visiting, I finally made it to the Wimbledon Windmill Museum, thanks to a well-timed running event and its medal design.

Sometimes You Just Need a Reason to Visit

About a decade ago, I lived a short walk from Wimbledon Common. In retrospect, I didn’t make the most of that particular geographical blessing. I walked there occasionally. Once going as far as Richmond and one of those pubs the Thames overwhelms on a regular basis. But I never quite ventured in the direction of the Windmill. I knew it was there, in a general sense. I might have even caught a glimpse of its sails across the heath once or twice. But like so many small local museums, it remained one of those things I always meant to visit… eventually.

The trouble is, once you move away, a place like the Wimbledon Windmill doesn’t exactly get easier to reach. It’s not inaccessible from South East London (a train or two and a bus will get you there) but it’s not a quick hop either. It would have lingered on my ‘must visit’ list if it weren’t for a 10K race on the Common. Not only did the route loop right past the Windmill. It turned out to be the central design on the finishers’ medal. That seemed like a sign. Having just run around it, it would have felt rude not to go take a closer look.

So we plotted a post-race wander through the woods, and found our way to the Wimbledon Windmill Museum. What we discovered was a charming, slightly time-warped little gem. It turns out that as well as being a race landmark, the windmill is a local curiosity, and a slice of engineering history.

Wind, Flour, and a Battle for the Common

The Wimbledon Windmill dates back to 1817, built by local craftsman Charles March. March’s mill answered a local demand: residents preferred milled flour ground nearby rather than factory-processed grain. Notably, its construction followed an earlier failed 1799 application by John Watney, who lacked formal plans.

Unusually for Britain, March’s mill was a “hollow-post” design, with the sail’s iron drive shaft funneled through a central post to operate the millstones below. It’s possible March copied a windmill near the Globe Theatre, and didn’t realise it was an unusual type. It served Wimbledon Common’s community until 1864, when the local lord of the manor, the 5th Earl Spencer, moved to enclose the Common and build on the Windmill’s site.

Local residents resisted fiercely. A six-year legal conflict culminated in the Wimbledon and Putney Commons Act of 1871, which preserved the Common for public use and granted management to elected conservators, preventing Spencer’s planned enclosure. As part of the conflict, the Earl bought out the miller’s lease, and the miller removed the machinery so that nobody else could compete with his family’s other mills.

Following its closure, the Windmill was converted into cottages housing six families, one of which is recreated in the museum. A major restoration in 1893 saw a number of changes including a new cap. From 1976 onwards, the building became a museum, with funding from the Heritage Lottery restoring its sails to working order.

The Visitor Experience: A Walk Through Lives, Tools, and Scouting History

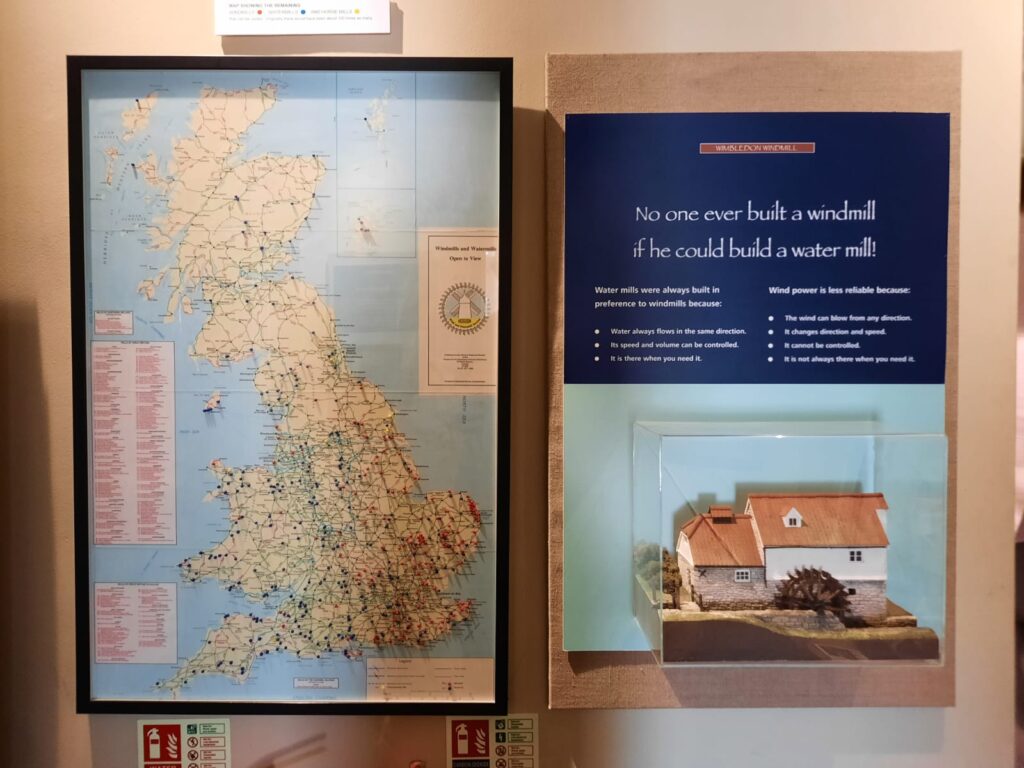

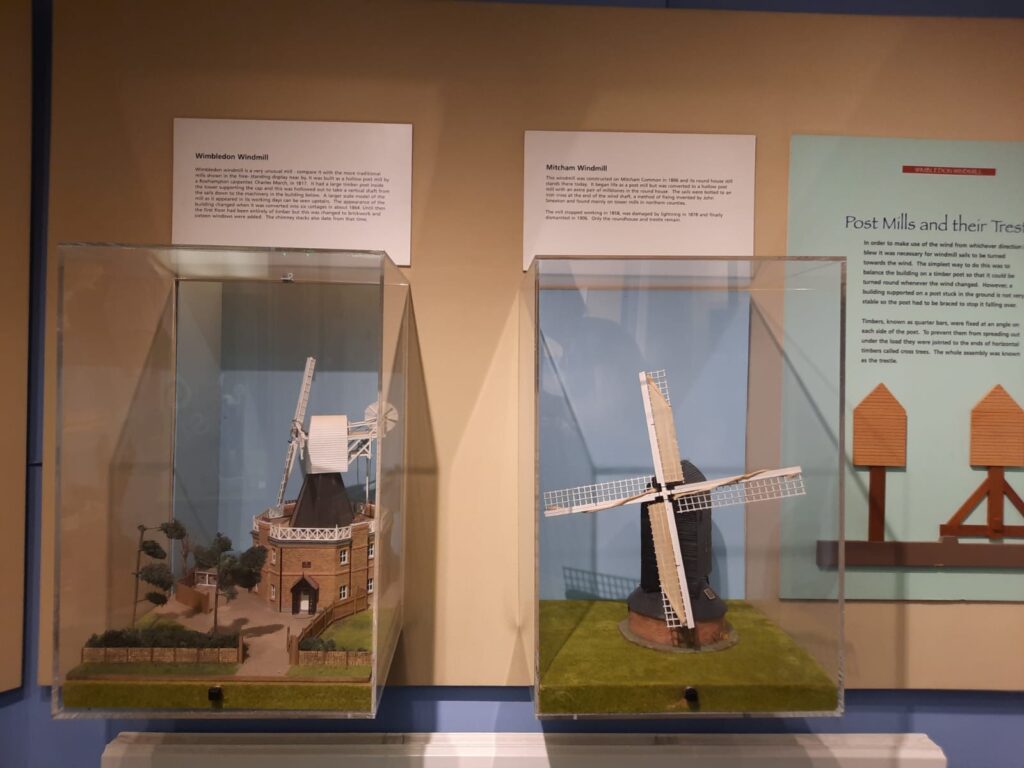

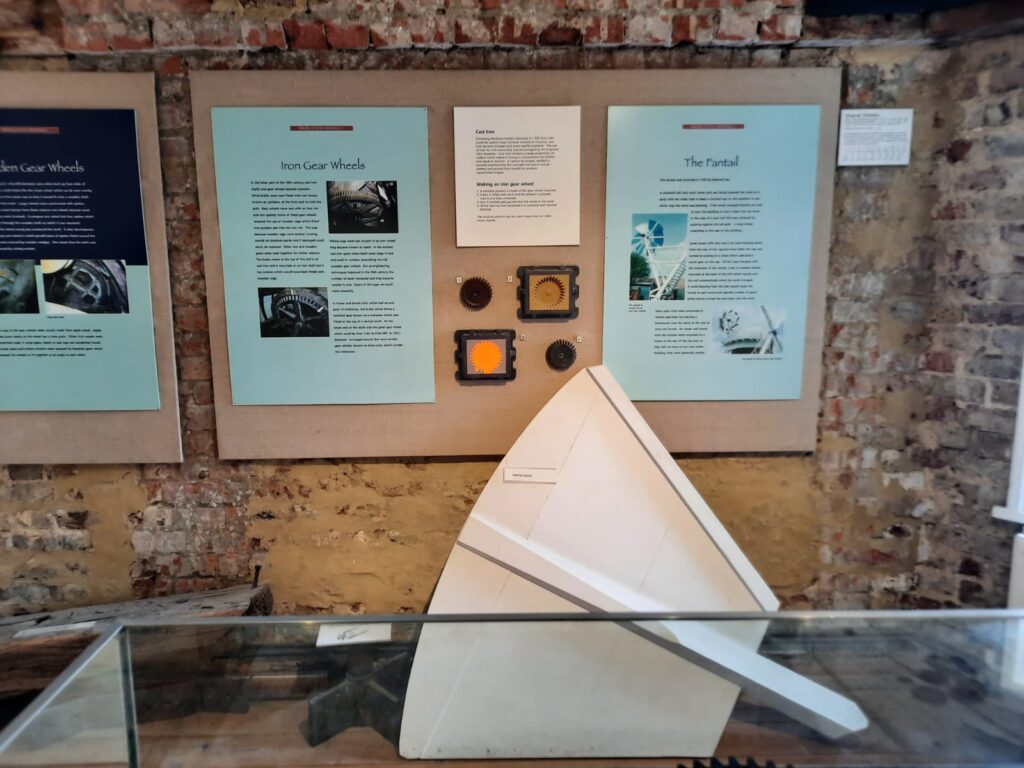

Stepping through the door, a friendly volunteer greeted us. The ground floor serves as an accessible introduction. A diorama shows the mill under construction, while a video focuses less on milling history and more on how the museum itself came to be: a quirky self-reflection. Nearby, an assembled collection of hand tools (not original to the site) gives a feel for the trades of the time. Also on view are scale models of various windmill types: common smock mills, hollow-post designs, and eccentric one-offs. A helpful primer in the evolution of wind-powered design.

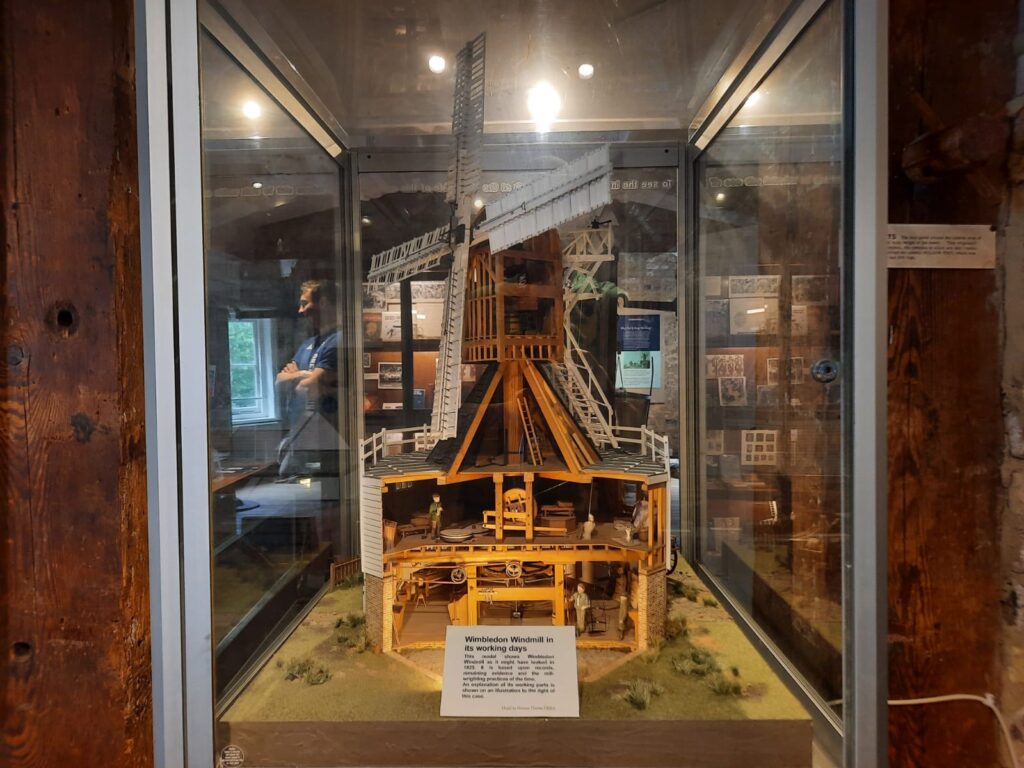

Upstairs, the focus narrows to this windmill’s unique story. A sizeable millstone dominates one side of the room, alongside a hand quern and saddle stone offering hands-on insight into older grain-grinding methods. A cutaway model shows how the sails, shaft, and stones interconnect, and a window looks out over more millstones in the garden, impressive in scale and craftsmanship. The small cottage stage of the windmill’s post-milling life is recreated on the other side. A mannequin stands in for a former resident, amid two compact rooms filled with her belongings. It’s not luxurious but seems serviceable, and the visitor senses the cadence of mid-Victorian daily life.

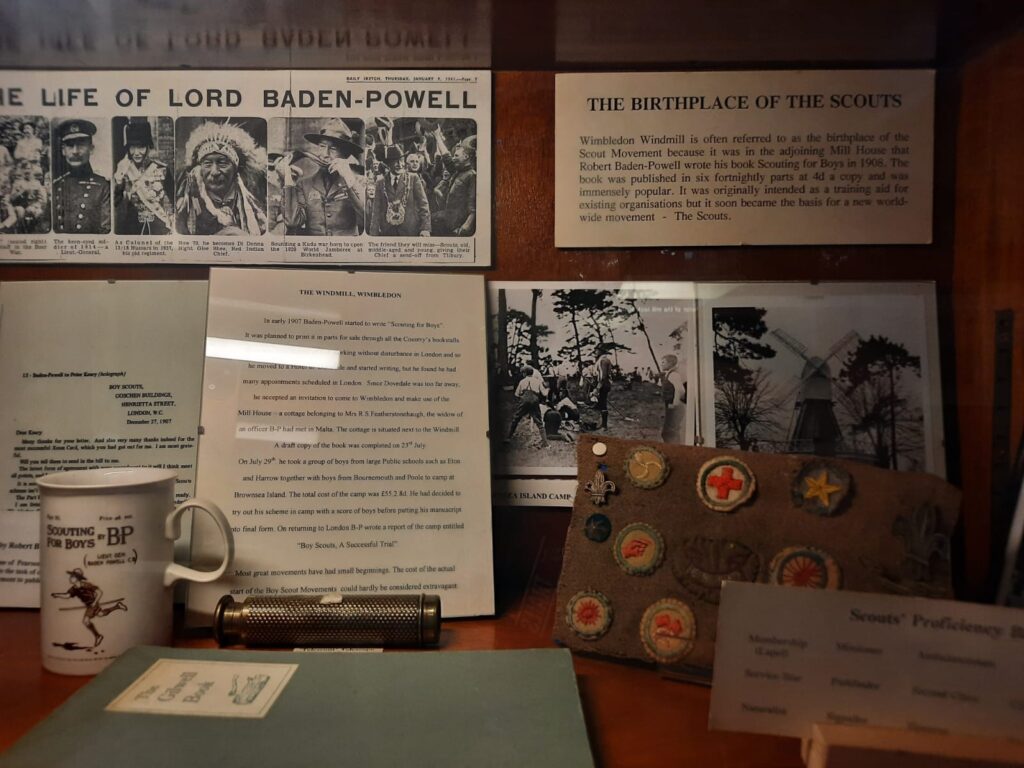

Finally, an unexpected postscript awaits in the form of scouting memorabilia. Robert Baden-Powell, the founder of the Scouting movement, spent time in the mill house in 1908 and is said to have written parts of Scouting for Boys here. A case holds vintage badges, early editions of his book, and newspaper articles, reminding visitors of another layer of social history rooted in the site.

Before descending, don’t miss the view up through the trapdoor: a glimpse of the windmill tower’s interior mechanics overhead. It leaves you with a final, inspiring sense of scale and the ingenuity the museum preserves.

Farewell to Wimbledon Common

The Wimbledon Windmill Museum might be one of London’s smaller museums, but it’s a lovely reminder that memory is embedded everywhere in this city, sometimes in unexpected corners of common land. It rewards the curious visitor with layers: agricultural, domestic, literary, even scouting history, all within a compact space.

If you can, it’s worth planning your visit to coincide with one of the regular demonstration days, when the sails are set in motion. That would certainly bring a new dimension to the experience: suddenly the mill is no longer a relic, but a living machine. The website has details, and I think it would be well worth the logistics to make the timing work.

There’s a café on site, which makes a useful stop before or after your visit, though be warned it can get very busy at peak times, especially when the weather’s good and the Common is full of walkers, cyclists, and families.

It’s not the easiest museum to reach if you’re coming from across London, but for those with an interest in local history, traditional engineering, or London’s quieter curiosities, it’s well worth the effort. You may not need to visit more than once, but you’ll be glad you did.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.