Le Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Montpellier’s main art museum, the Musée Fabre combines collections and acquisitions to form a classic art historical overview in a historic setting.

Just Enough Time for One Museum

If you’ve been following the blog, you’ll have been expecting this post. My last entry was a whistle stop tour of Montpellier, in the South of France. The Urban Geographer and I spent an afternoon here between spending time in the countryside in the Hérault region, and flying back to London.

It was the first time visiting Montpellier for both of us, so we wanted to get out and see the city. But we still had time, just about, for a visit to a museum. We did this first, so we had the rest of the afternoon to play with. But which museum to choose?

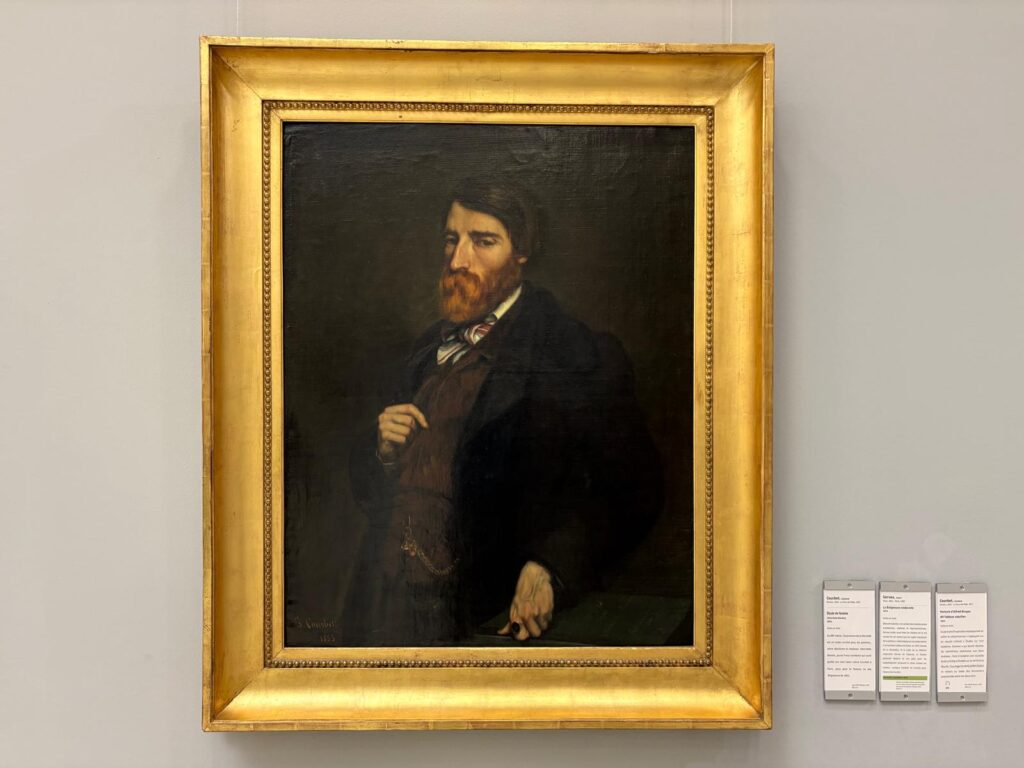

Well, thankfully, Montpellier made it easy. On the one hand, the Musée Fabre’s reputation precedes it. It is one of 60 or so Musées de France, institutions whose collections or other unique factors elevate them to a status of national importance. Plus I really fancied seeing La Rencontre by Gustave Courbet: a favourite of art history textbooks. Also a factor, a number of Montpellier’s museums were closed when we visited. And several of these were the type I would normally make a beeline for: historic university museums. But never mind, hopefully there will be a return visit at some stage. And, as I say, it made the choice easy.

So after walking up from the train station and leaving our bags at the hotel, we headed for the Musée Fabre.

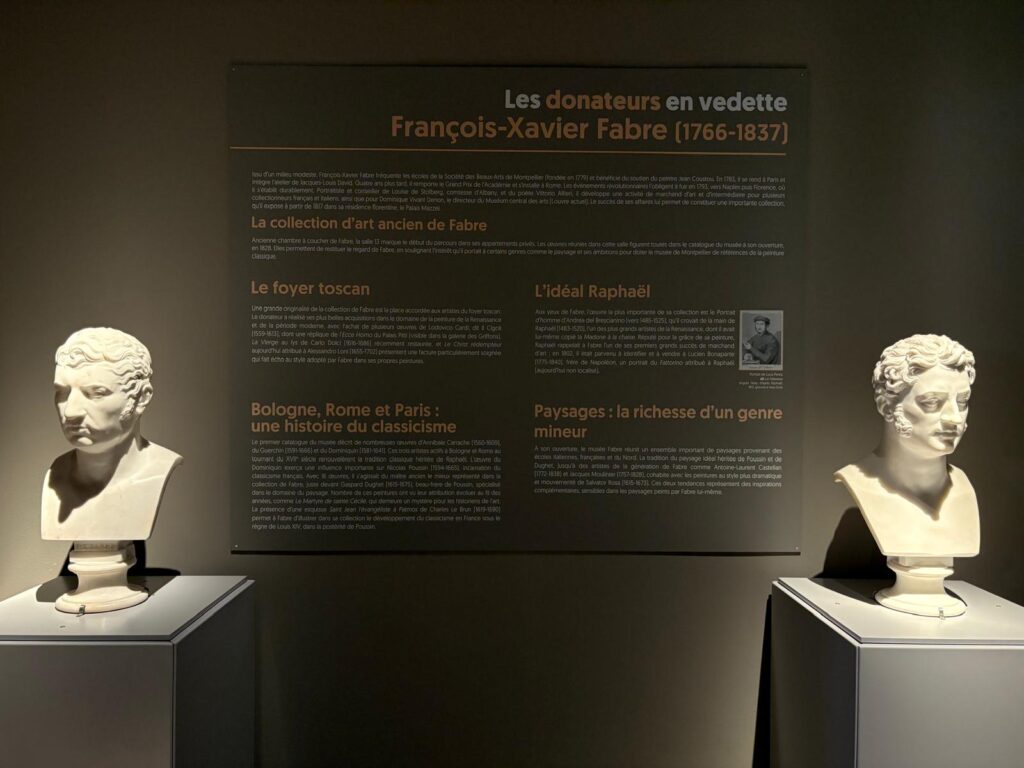

Le Musée Fabre – François-Xavier Fabre

The history of the Musée Fabre goes back a little further than the Fabre name. In 1802, the city of Montpellier received a donation of around thirty paintings. This allowed them to establish a small municipal museum, which moved between various temporary locations. But it’s when Fabre got involved that the museum grew to a completely different scale.

François-Xavier Fabre was a French painter in the Academic style, born in 1766. He was a student of Jacques-Louis David. He first made a name for himself by winning the Prix de Rome in 1787 – this was a scholarship awarded by the King that allowed an artist to live and study in Rome for 3-5 years. It seems to have been of such importance it survived the French Revolution, and it was a very big deal. David, Fabre’s teacher, apparently considered suicide when he repeatedly failed to win it.

The other thing Fabre did to establish himself was some sort of involvement – possibly marriage – with Princess Louise of Stolberg-Gedern, Countess of Albany. Whatever their connection was, Fabre inherited Louise’s fortune on her death. He used it to establish an art school in Montpellier, his home town. In 1825 he donated a large number of paintings to the city, enabling the expansion of the museum. When he died in 1837, he bequeathed the remainder of his art collection to the city.

I have failed to find much information about how Montpellier acquired the Hôtel de Massillian, but somehow it did (revolutionary expropriation is one guess?). As I mentioned in my last post, here we are using the word hôtel in the sense of a private mansion, not a hotel you stay in. The coming together of the Fabre collection and the Hôtel de Massillian in 1828 was the basis of the Musée Fabre as we know it today.

Le Musée Fabre – Subsequent Development

Fabre’s donations encouraged others to follow suit, even within his lifetime. Antoine Valedau donated a collection of Flemish and Dutch Old Masters in 1836. Art collector Jules Bonnet-Mel from nearby Pézenas donated 400 drawings and 28 paintings in 1864. In 1868, Alfred Bruyas gave the city the works from his personal gallery (a lot more on him shortly). It was the turn of Jules Canonge in 1870, donating more than 350 drawings. And then Bruyas again in 1877 when he left more than 200 additional works to the collection. When you think the initial collection was just thirty or so paintings, that’s a very substantial increase over the 19th century.

In the 20th century there was another step change. In 1968, Madame Pierre Sabatier d’Espeyran followed the wishes of her late husband and donated a second hôtel particulier along with its contents, including an extensive library. This enabled the Musée Fabre to spin up a second site focused on decorative arts. In 2001 the library moved out, allowing for modernisation and refocusing of the Hôtel Cabrières-Sabatier d’Espeyran.

So from humble beginnings, the Musée Fabre has grown into a formidable museum. No wonder it’s one of the Musées de France. The donations I listed above are not the only works in the collection, which covers art history from the Old Masters to Post-Impressionism (with a few forays outside this, from classical sculpture to modern artists). We are going to spend just a little bit more time on one of those private collections, however, before we get into the experience for visitors today.

How Donations Shape a Museum: Alfred Bruyas

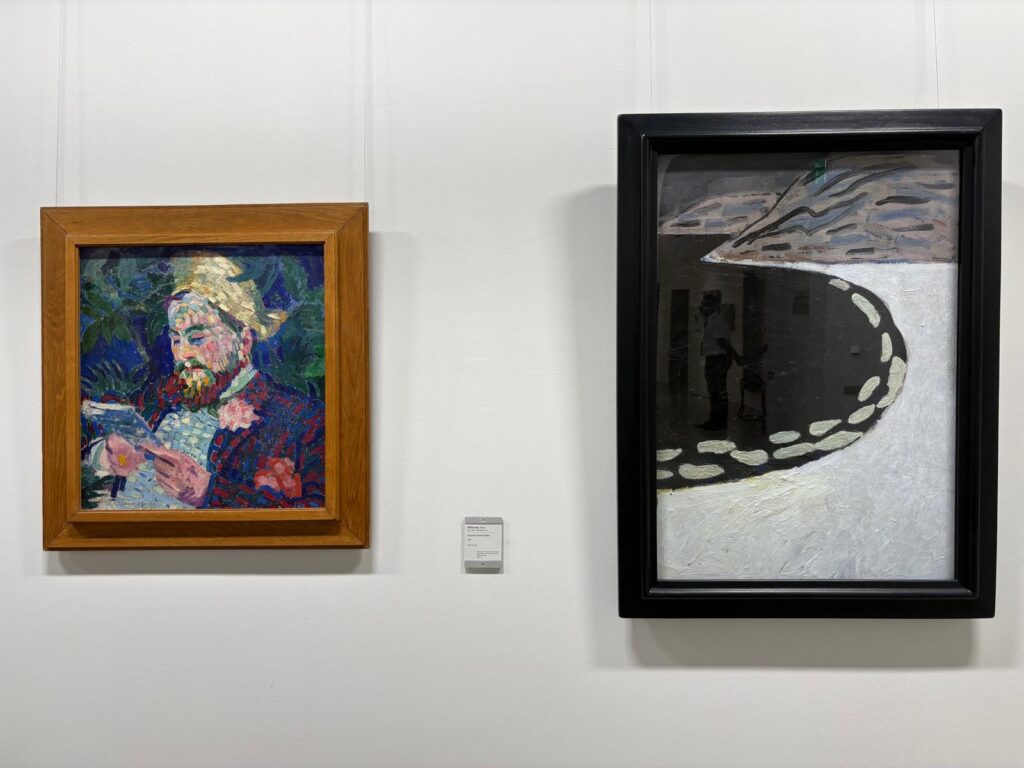

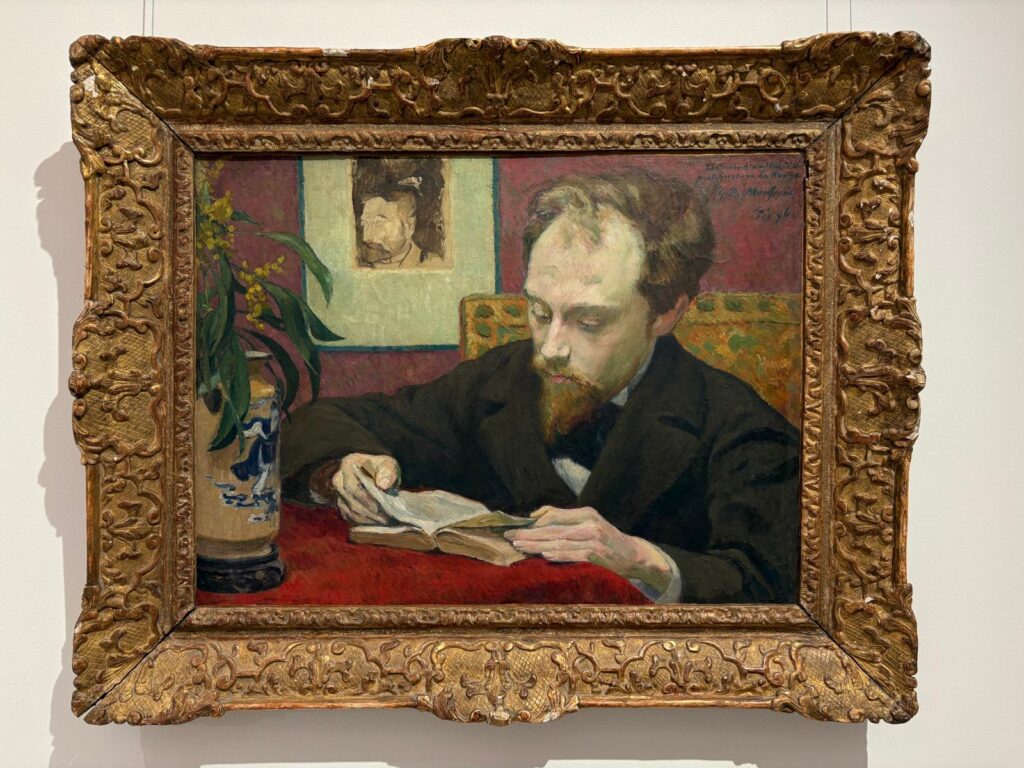

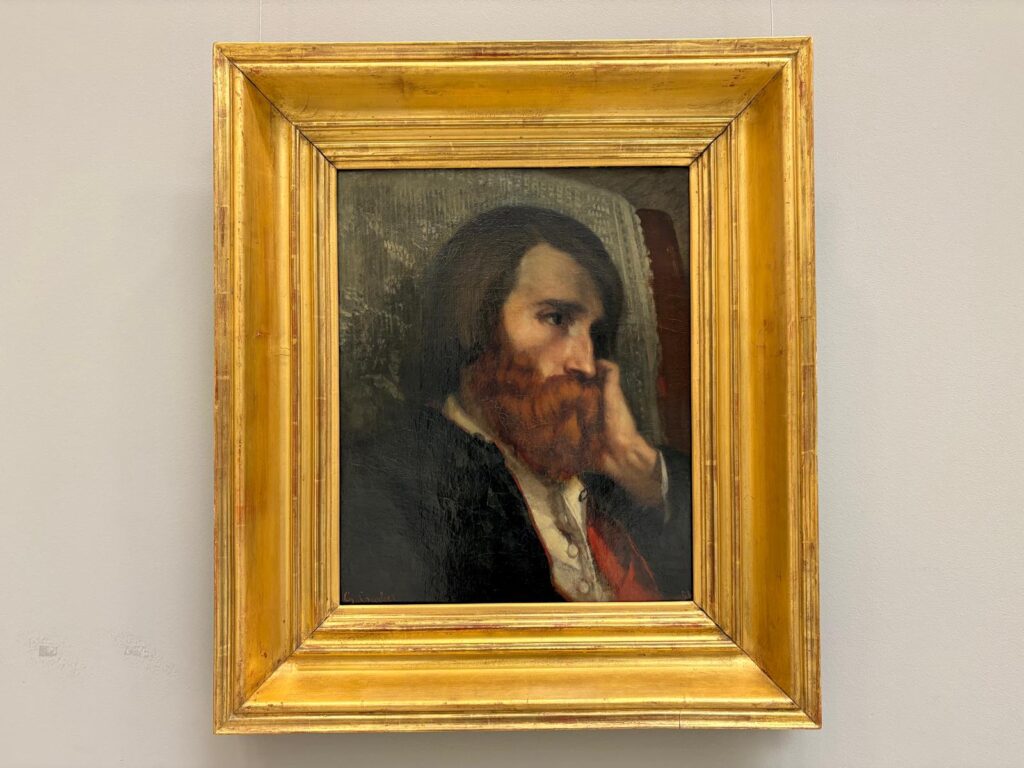

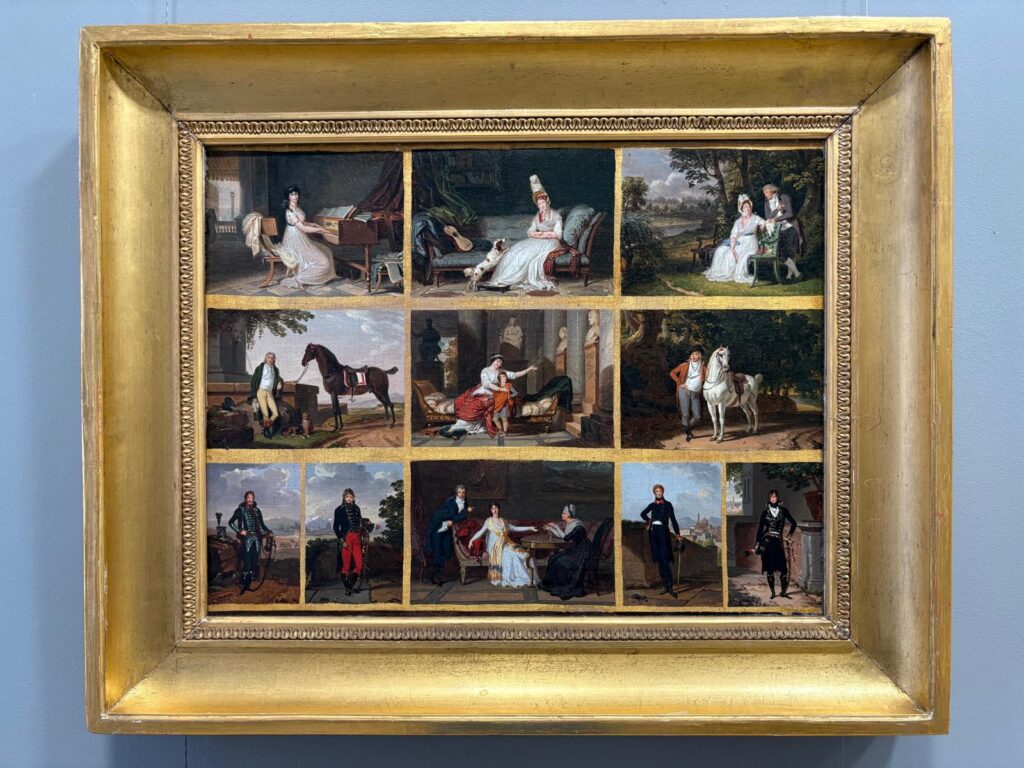

Do you notice something the images above have in common? A consistent face peering out of most of the canvases, perhaps? Meet Alfred Bruyas, one of the donors I mentioned above. Born in Montpellier in 1821, Bruyas was the son of a banker. He had aspirations of becoming an artist, studying under painter Charles Matet, who actually worked at the Musée Fabre (then the Musée de Montpellier) at the time. He soon realised, however, that he would make a bigger contribution to art as a patron.

Living in Paris for a time, Bruyas began to amass a collection, including works by Camille Corot, Eugène Delacroix, Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and others. But it was to Gustave Courbet’s career that he made the biggest impact, acting as patron and allowing Courbet to focus on his art.

Several of the works above are by Courbet, but not all of them. But something many of the works from the Bruyas collection have in common is that they contain portraits of the man himself. I found myself thinking about a line from the film Amélie, in which she speculates that a mysterious figure found in multiple discarded ID photos might be a ghost afraid of being forgotten. Because, you see, Bruyas suffered from consumption from an early age, so would have known his time was limited (although he died at 55, not bad going all things considered). Did he instruct all those artists to capture his likeness as a way of living on after death?

Whatever the reason, it is a nice illustration of the impact of donations by art collectors on museums. Art is such a personal thing. Which artists you like, which styles you enjoy, varies from person to person. And as we see here, when you’re calling the shots, you get a say over the subject matter, too. When your art then ends up in a public collection, it takes that collection in a particular direction. I’ve never seen so many likenesses of the same person in one museum, especially when they’re not the primary focus, and not even the guy the museum is named after! It became a sort of sport for me as I walked the Musée Fabre: Bruyas-spotting. To that end, please enjoy a bonus gallery at the end of this post with a few more works.

A Reverse Journey Through Art History

So, after that Bruyas detour, back to regular programming. And it’s time now to tell you about my experience visiting the Musée Fabre. Like most museums in France, entrance is ticketed, and there are a few options. In our case, we went for a ticket including both the permanent collection and the temporary exhibition. The exhibition, on Pierre Soulages, will be the subject of my next post. But as the entrance to the exhibition is right next to the ticket desks, it’s there that we started.

In hindsight, although it was nice to see the exhibition first and then decide how much time to devote to the rest of the collection, it did make for a strange visitor experience. Another donation to the Musée Fabre was by Soulages himself. Soulages, who died in 2022 at the age of 102, was born in Montpellier. In 2005, he donated 20 canvasses to the Musée Fabre. These are displayed in dedicated rooms, laid out according to the vision of the artist. And it’s here, quite sensibly, that the temporary exhibition deposits visitors as a kind of extension to the exhibition itself.

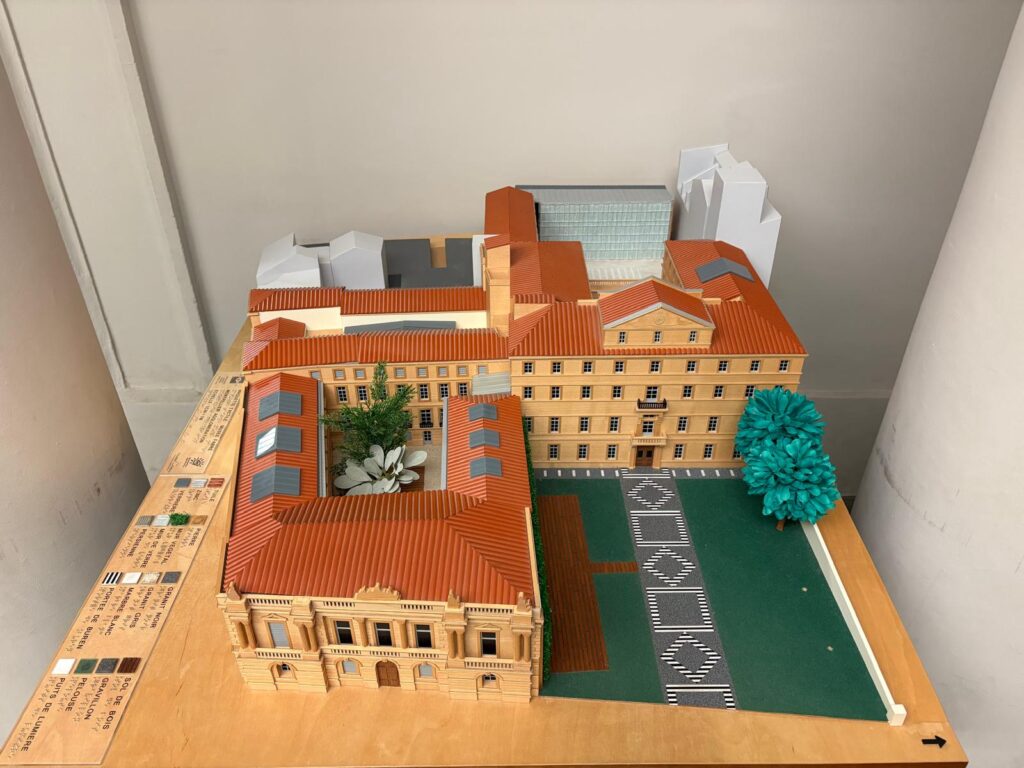

That means, however, that visitors then make their way backwards through art history. From one of the most contemporary artists in the museum’s collection, you trace your way back through Modernists, Post-Impressionists, Impressionists, Academicians including Neo-Classical, Orientalist and so on (this is where we find Bruyas), to 18th century works and finally Old Masters. If you look back at the images in this post so far, it’s this journey that they take. It’s a little peculiar working backwards like this. And I don’t know if this was entirely the reason, but I did get very confused by the building’s layout. Would it make more sense working start to finish instead of finish to start, or is it just confusing? One of the last images in this post shows a maquette of the building which might help you determine the answer to that question.

A Few Highlights

Exiting the temporary exhibition into the permanent Soulages space subverted my expectations of what the museum would be. Here was a space that was light, airy, very modern. Not the hôtel particulier I knew I had entered not long ago. This was, as I learned from the maquette (and could probably have guessed), a newer extension. It is a great space for Soulages’ paintings, though, and nice to know you’re seeing them just as he envisaged.

The other modern and (more) contemporary works didn’t thrill me. I did like the Post-Impressionists and Fauvists, though. There were artists I recognised, like Kees van Dongen, but a lot of new discoveries as well. None of the paintings were superstars on their own, but together they give a good overview of where art headed after the Impressionists ruptured with the Academic tradition.

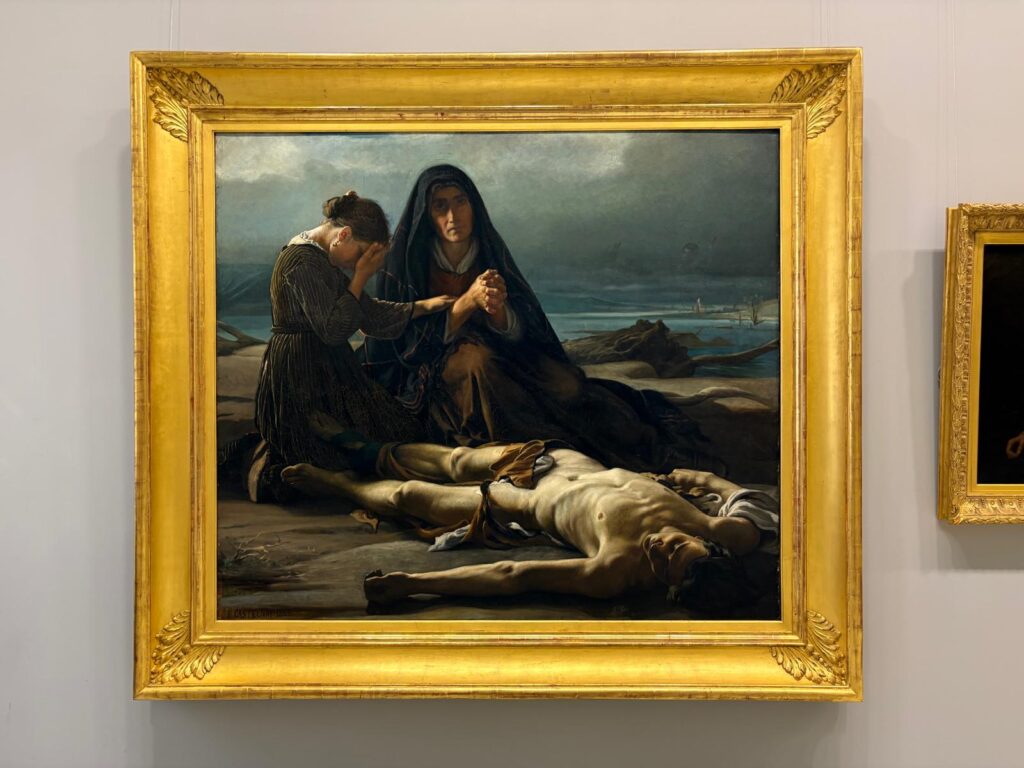

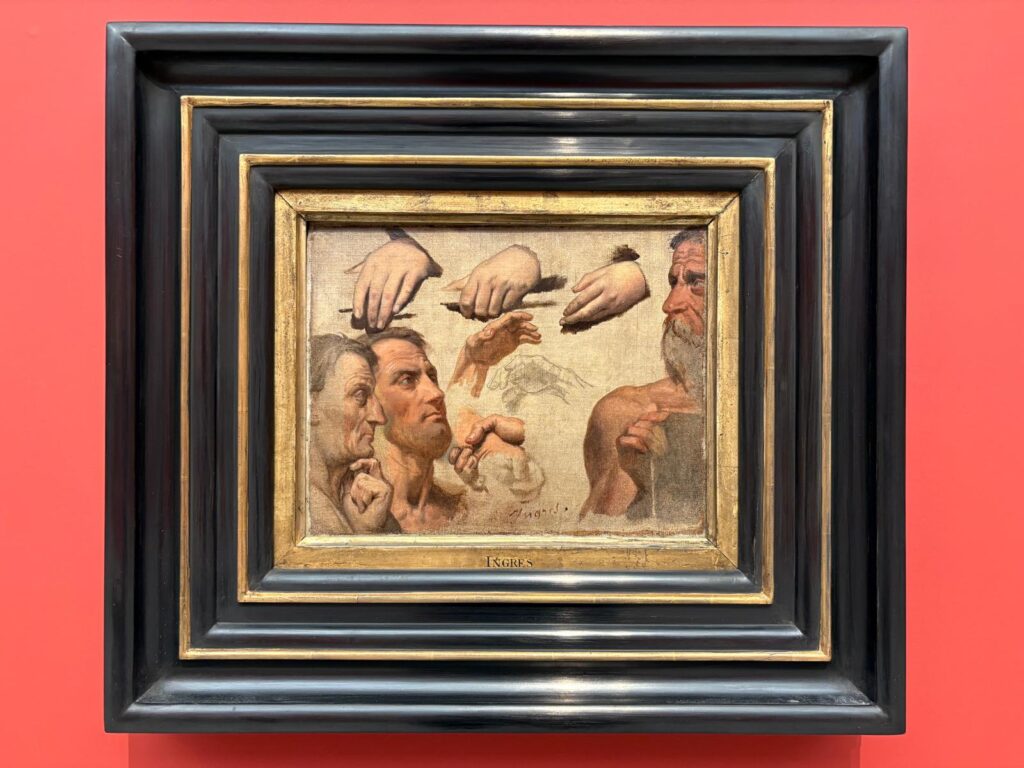

Next (working backwards, remember), I encountered those Academic painters. I absolutely loved the sport of Bruyas-spotting. This perhaps made me less observant when it came to paintings not featuring our main man Alfred. But the collection here is again a solid overview of different traditions, themes and styles within the art of the period.

The 18th century works were surprisingly interesting. It’s not a period that’s of particular interest to me normally, and I did skim over some of the more densely hung rooms. But there were some unusual and eye-catching ones in there too. Nothing as eye-catching as the next galleries, though. You can see them below. The museum suddenly switches from fairly neutral backdrops to bright colours, columns, and mosaic floors. This dramatic setting really works with the paintings they’ve hung in this room. I believe at one point this may have been where the Bruyas collection was displayed.

Perhaps because I’d covered a substantial distance by this point (including doubling back to collect the Urban Geographer who was taking a break, then getting lost), the Old Masters were the least interesting. Again a few nice works, but overall a fairly small collection. And with that our visit was complete. A reverse journey through (Western) art history, consisting of various private collections and presumably some additional acquisitions to round things out.

Where to From Here?

One thought that struck me as I wandered the Musée Fabre’s corridors was about the future. The museum does a great job at telling the story of (again Western) art history. But what about the future? I suspect the museum’s past shapes it to a significant degree.

What do I mean by that? Well, I’m not sure about the particulars, but it would not surprise me at all if at least some of the major donations came with stipulations about being on display. Nobody wants to donate their collection for it to end up in storage, after all. And the museum, despite its modern extension, is full. Expanding the displays to include more contemporary art would not be easy.

That is not to say that there is nothing contemporary here. There are a couple of contemporary interventions within the museum, notably in a big white cube space near the entrance. Using this space to the fullest, and perhaps putting contemporary art “in dialogue” with the historic collection, would be two ways to avoid the museum being a time capsule. Or you could accept that not every museum can do everything, and go to MO.CO. for contemporary art.

Does it matter? Maybe not. As we’ve explored throughout this post, the Musée Fabre at one and the same time displays a series of artworks from different time periods, and tells the story of its own development through the works and collections on view. That’s not bad going.

Final Thoughts

For a first trip to Montpellier with limited time to spare, I think we chose well coming to the Musée Fabre. I got to see that work by Courbet, for a start. It lived up to my expectations. We saw a lot of impressive artworks. And some middling ones which also told a story. We learned about notable former residents of Montpellier, both artists and patrons. And I personally found some of the different architectural spaces inspiring as well.

On a return visit, I would like to explore some of the city’s smaller museums. Perhaps some of those university museums, if they’re open. But those visits would be informed by what I learned about Montpellier during my trip to the Musée Fabre and afternoon wandering around. It’s a fairly accessible city (in the intellectual sense – I guess also OK in the physical sense?), and even a brief visit is rewarding.

If you do visit the Musée Fabre, please consider doing a bit of Bruyas-spotting yourself. Can you beat my record? I think there are 18, possibly 19 images of him throughout this post. If this was an attempt not to be forgotten, it has most definitely succeeded.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Bonus Gallery! How Many More Likenesses of Alfred Bruyas Can You Spot?