Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva (Кыргызский Национальный Музей Изобразительных Искусств имeни Гапара Айтиева), Bishkek

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva brings together applied and fine arts in a unique Soviet Brutalist building. Great for learning about the 20th century development of the arts in Kyrgyzstan.

Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva

We’re continuing our tour of museums in Bishkek today, by visiting the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva. My last post described a visit to the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic. In it, I talked about the ‘fetishisation’ of the Soviet period: that desire to ‘experience’ something of a very different time, through time capsule museums for instance. I hinted that some of the other museums I visited in Bishkek would fall more within that category than the National History Museum, which, after an extensive renovation, is more in the international style.

The Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva is something of a middle ground. If there’s a spectrum from modern museum to time capsule, the National History Museum falls at one end, and our next stop in Bishkek is at the other. The National Museum of Fine Arts gives a strong sense of history, and certainly has a great collection of Socialist Realist art, but also contains elements which suggest it has shifted its focus and its presentation of traditional Kyrgyz artforms in a post-independence context.

In my last post I also said that, where museums in Bishkek have less extensively modernised themselves, this is likely due to resources rather than a lack of willing. I suspect this is the case here. The museum has a sort of worn appearance that speaks to making do on a budget. It does give an opportunity to see the original design, however. Walking around the galleries I could imagine them transformed into modern, white cube spaces. But for my money, I liked the warmth of the original wood (if not the warmth of the inadequate air conditioning). This feels again like a bit of a museologist’s quandary: what I personally enjoy in a museum visit vs. what is best for the museum itself and its local community.

A Brief History of the National Museum of Fine Arts

Like the National History Museum of the Kyrgyz Republic, the National Museum of Fine Arts got its start in the early Soviet period. From this we can deduce that, during the Russian Empire period, urbanisation, nation-building and so on were less of a priority in this far-flung outpost of Empire. The Soviet administration, meanwhile, aimed to replicate itself all over the USSR. Modern, planned cities were signs of Progress (with a capital P). And museums and art galleries organised along the right lines were not bourgeois decadence, but the means to preserve and promote cultural heritage and patriotism.

So then, in 1934 we see the founding of the Kyrgyz State Museum of Fine Arts. The foundational collection was of 72 works by Russian artists, selected by local artist S. A. Chuikov with the support of the State Tretyakov Gallery and the People’s Commissariat of the RSFSR (the state communication bureau). Works by Kyrgyz artists and others joined the collection over the years, with continuing support from various Soviet institutions and government branches. There are plenty of works by Russian/Soviet artists as well, and a small collection of Western art.

In the 1960s the collection expanded to include Kyrgyz applied art. Today there are over 3,000 such objects in the collection. This is a significant overlap with what the National History Museum covers: to be honest you could visit just one of these institutions and get a decent overview of local textiles, leatherwork, woodwork, jewellery, etc. Which one you visit would depend on whether you’re more interested in 20th century history, or 20th century art.

And what of the building? It’s a great example of Soviet Brutalism, dating to 1974 and designed by Kyrgyz architect Shailo Djekshenbaev. Djekshenbaev considered it a Gesamtkunstwerk: the museum itself is part of the exhibit and experience.

Tell Me More About SA. Chuikov and Gapar Aitiev

You got it. Let’s start with Semyon Afanasyevich Chuikov, who was born to a Russian family in Pishpek (now Bishkek) in 1902. He started his studies in Central Asia at a teacher’s seminary then art school, before heading to Moscow and the Vkhutemas (state art and technical school) in 1920. He taught at the Institute of Proletarian Fine Arts in Leningrad from 1930-32, before heading back to the Kyrgyz SSR and focusing in the following decades on developing the art scene locally (although he maintained a strong connection with Moscow and taught there for a time in the 1940s). The state art school in Frunze (also now Bishkek) was named after him. He travelled extensively, held exhibitions, was the People’s Artist of the USSR in 1963, and died in 1980.

Gapar Aitiev was one of the first Kyrgyz professional artists, born in 1912. He studied at the Moscow IsoTechnical Institute from 1935 to 1938. He blended Soviet and Kyrgyz elements in his work, and was also a notable figure in the arts in the Kyrgyz SSR, serving three times as Chairman of the Board of the Union of Artists. Aitiev led the painting workshop at the USSR Academy of Arts in Frunze. He also participated in the Great Patriotic War (WWII) and won various Soviet honours. He died in 1984.

Both important figures who worked hard to promote the arts in their home country, then. If I had to put forward a theory as to why the museum is named for Aitiev and not Chuikov, it would be that Aitiev was ethnically Kyrgyz. As with the switch from Frunze to Bishkek, locally-born Russian heroes were less at the forefront as an independent Kyrgyzstan figured out its identity post-1991. The museum owes a lot to Chuikov’s efforts, nonetheless.

Traditional Applied Arts

OK, we’ve covered the background. Now let’s get into the visitor experience at the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva. And we will start where visitors start, with the ethnographic collection. Or traditional applied arts, in an art gallery rather than museum context.

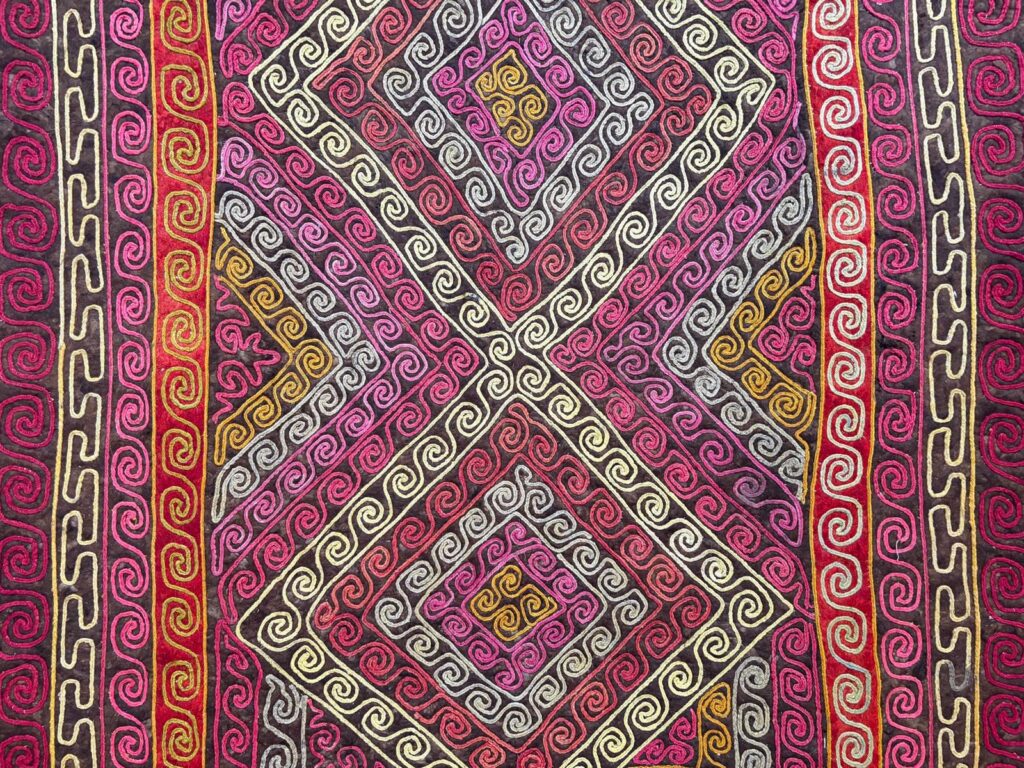

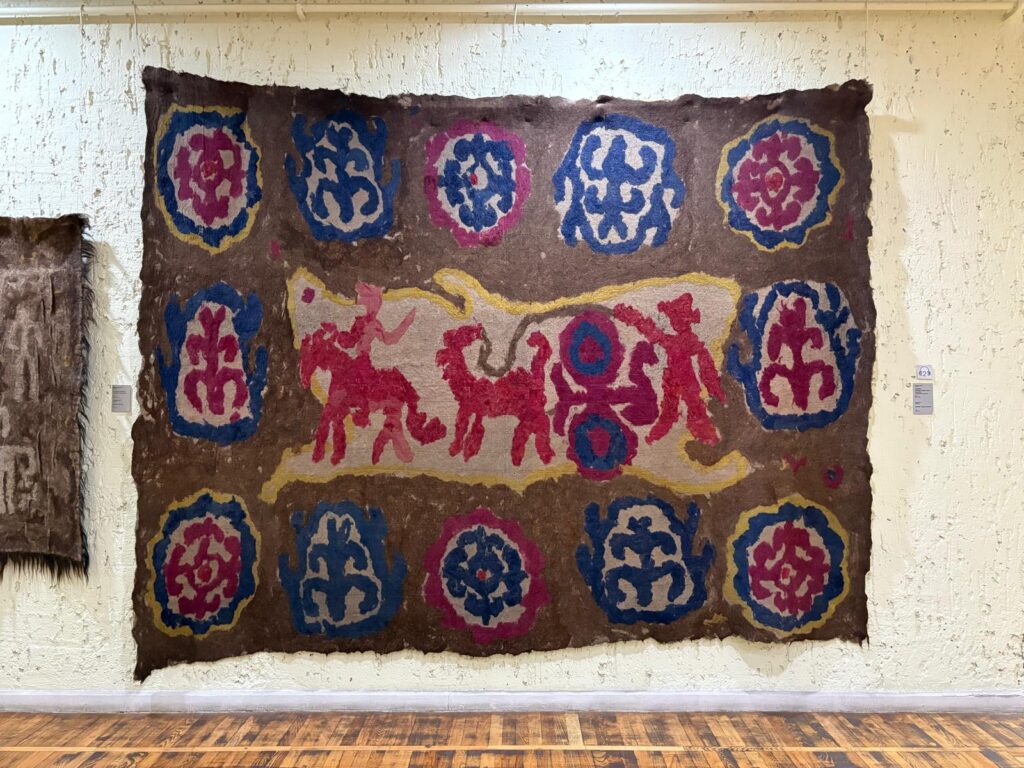

A visit starts on the museum’s first floor, in a large foyer space with some natural light. Here are arranged various types of traditional craft which start to become familiar after a while in Kyrgyzstan. Felted woolen carpets, leather food containers, and the like. As with the National History Museum, the bulk of the objects date to the 20th century. There are a few older pieces, though: some of the jewellery is late 19th century. Something neither institution really acknowledges is how these examples vary from strictly traditional forms: the use of dyes in the carpets, for instance.

This foyer space of applied art could feel like an afterthought. The rest of the collection is arranged in galleries tracing a square around this central space. There is a transitional room first, though. Entering this room, the visitor sees examples of mostly 20th century artists taking these techniques and adapting them. Large-scale felted works line the walls. Overhead is the distinctive shape of a tunduk, the central piece of a Kyrgyz yurt, symbolising family and the universe. Porcelain plates representing Yuri Gagarin amongst others prepare the visitor for the Socialist Realism to come. To me this was a signal that setting the collection within a distinctly Kyrgyz lineage and artistic context matters.

Socialist Realism (and Beyond)

Speaking of Socialist Realism, we’ve arrived. Interestingly, the style is almost exactly as old as the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva. From the First Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, Socialist Realism became the only acceptable artistic style across the USSR. The official objective was “to depict reality in its revolutionary development”. Artworks were to show the ideal Soviet society, both in the present and the future. This meant a sort of forced optimism, and the elevation of common workers (agricultural and industrial) to rosy-cheeked, ideologically-committed heroes.

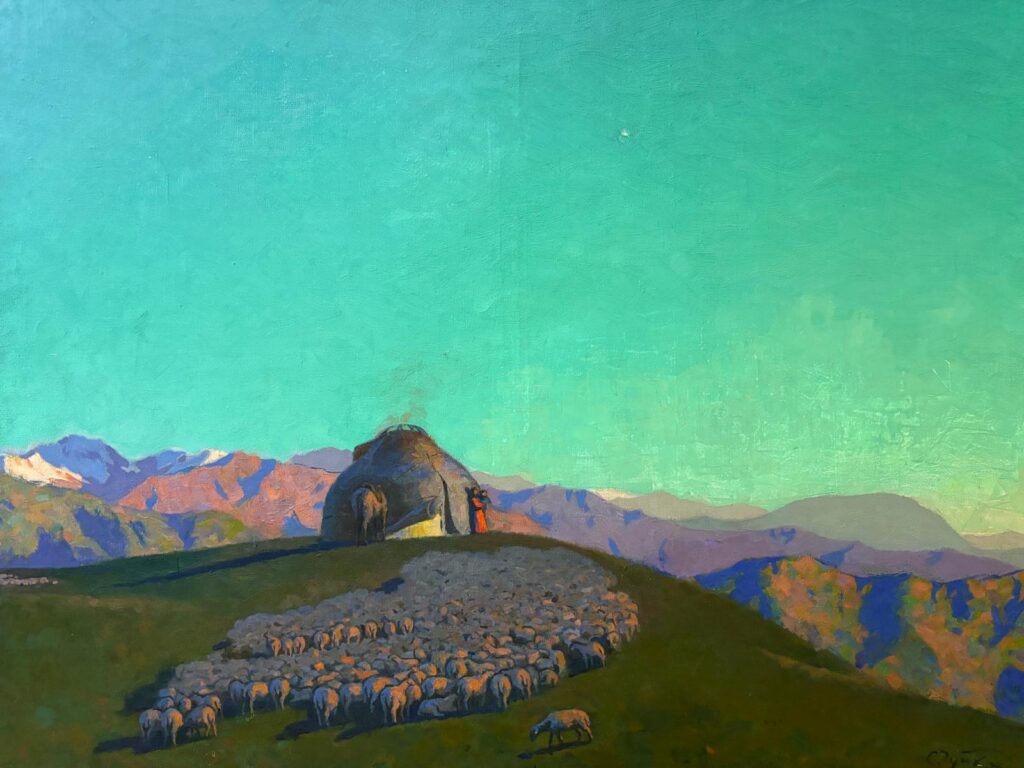

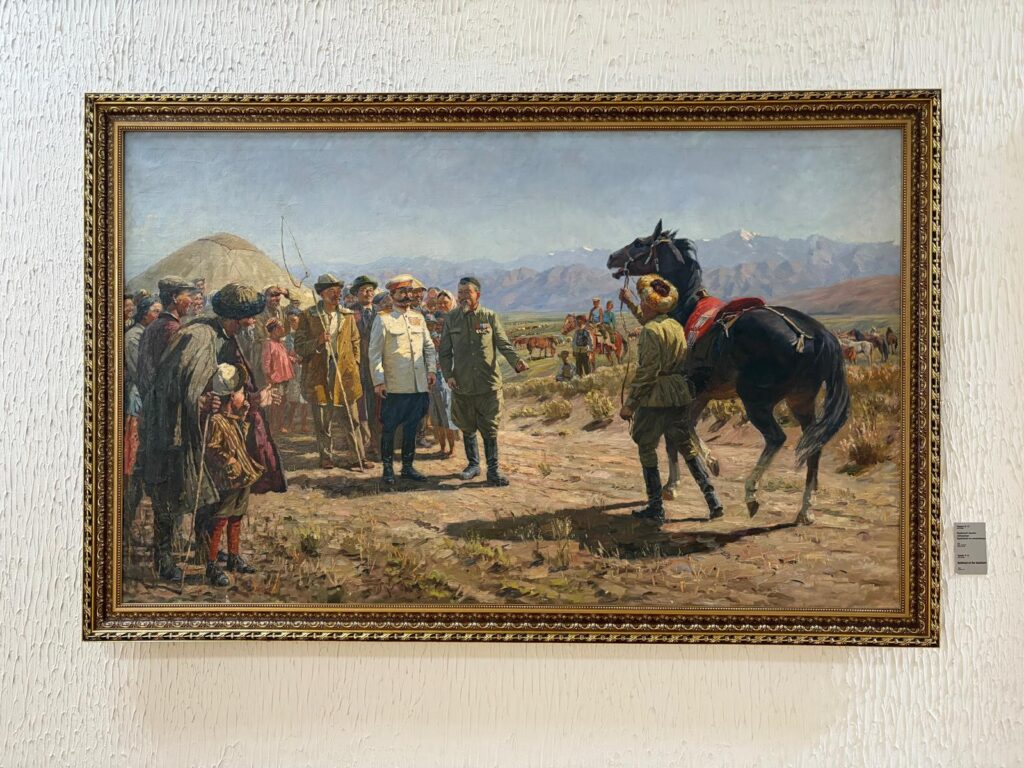

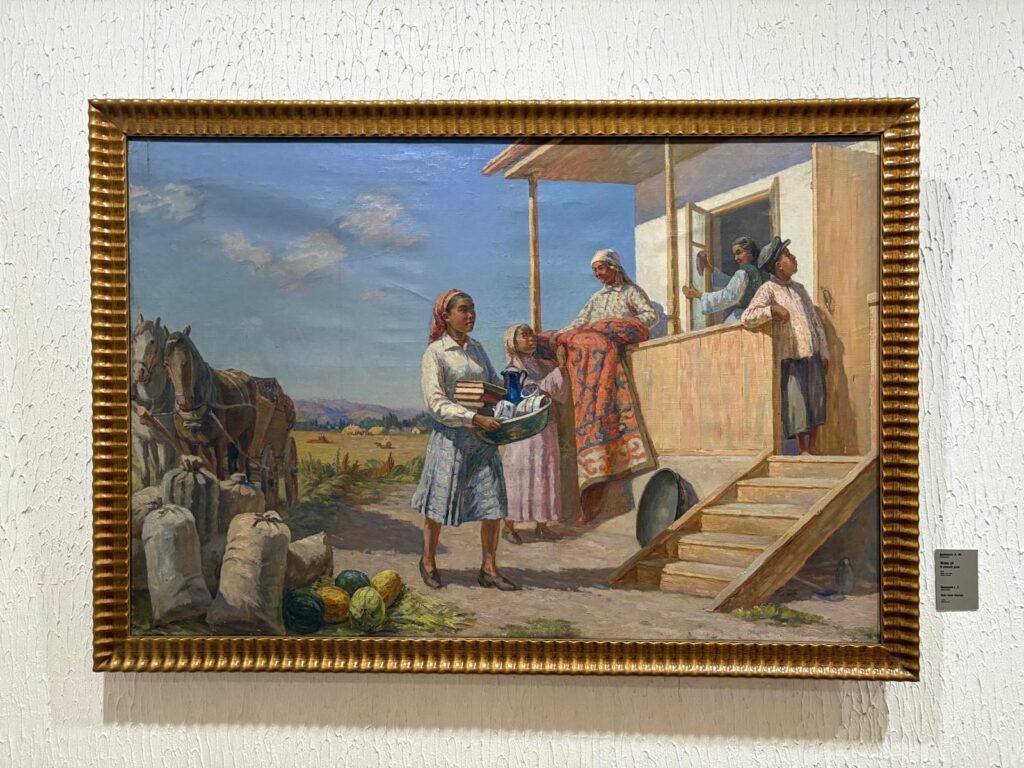

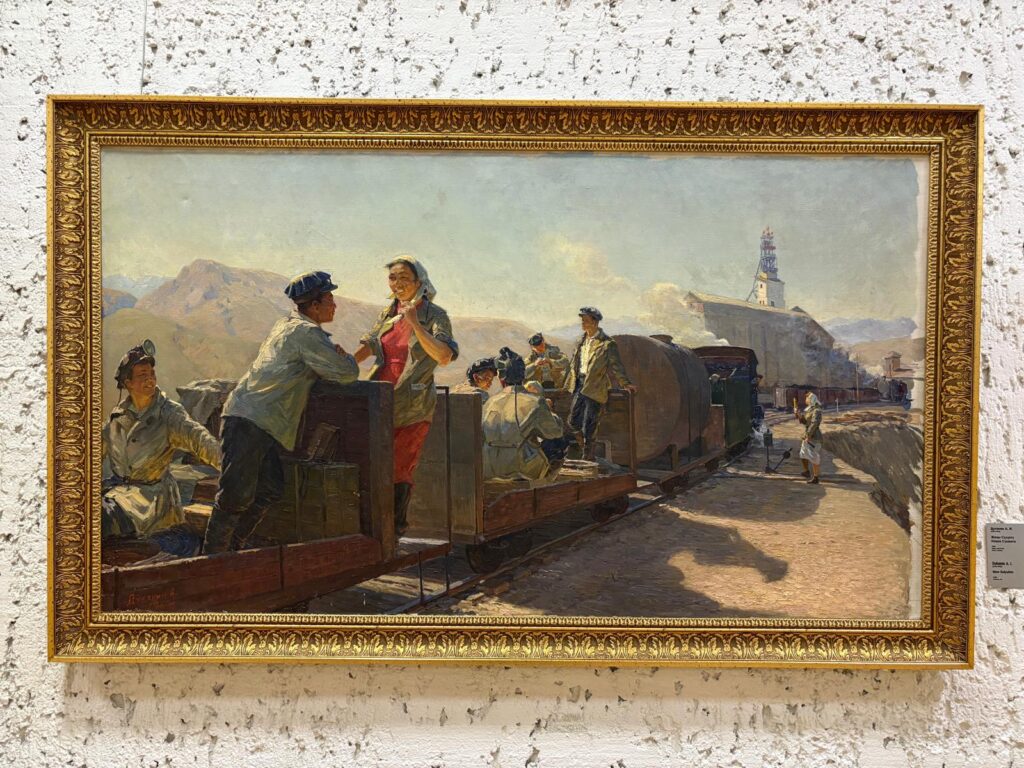

I would say almost half of the museum’s floorspace contains works in this style. It’s interesting to see the style transported to a Kyrgyz context, though. We see purposeful citizens on clean city or village streets, going about their business. Women in fairly traditional dress smile at glowing children, the abundance of collectivised harvests spilling out around them. Officials make their visits. Youths clutch books, showing the drive towards universal literacy. A Socialist utopia. For quite a while Kyrgyzstan’s professional artists were trained in Russia, so it makes sense they adhered so closely to this style. Plus, there was no choice if they did want to be professional artists.

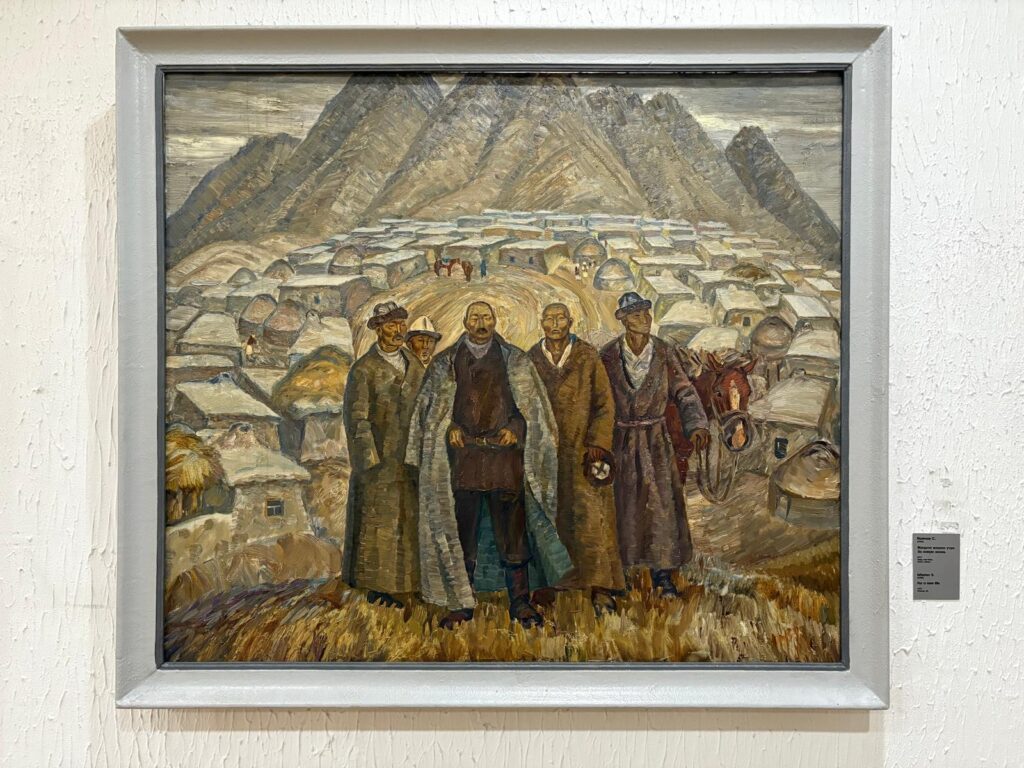

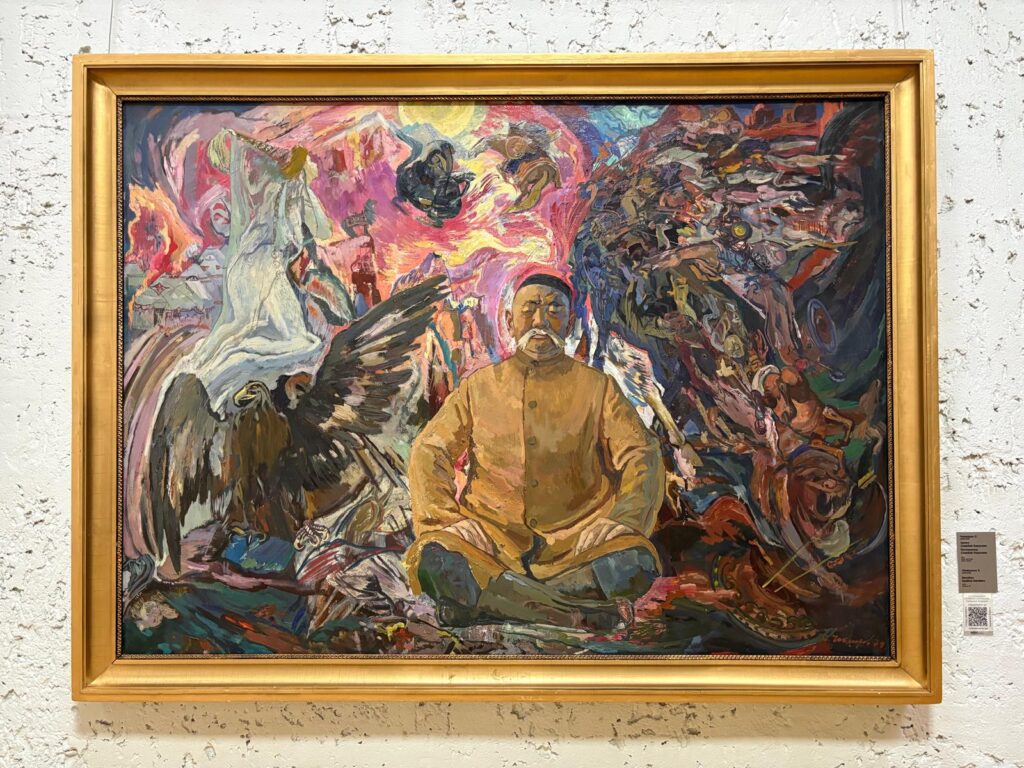

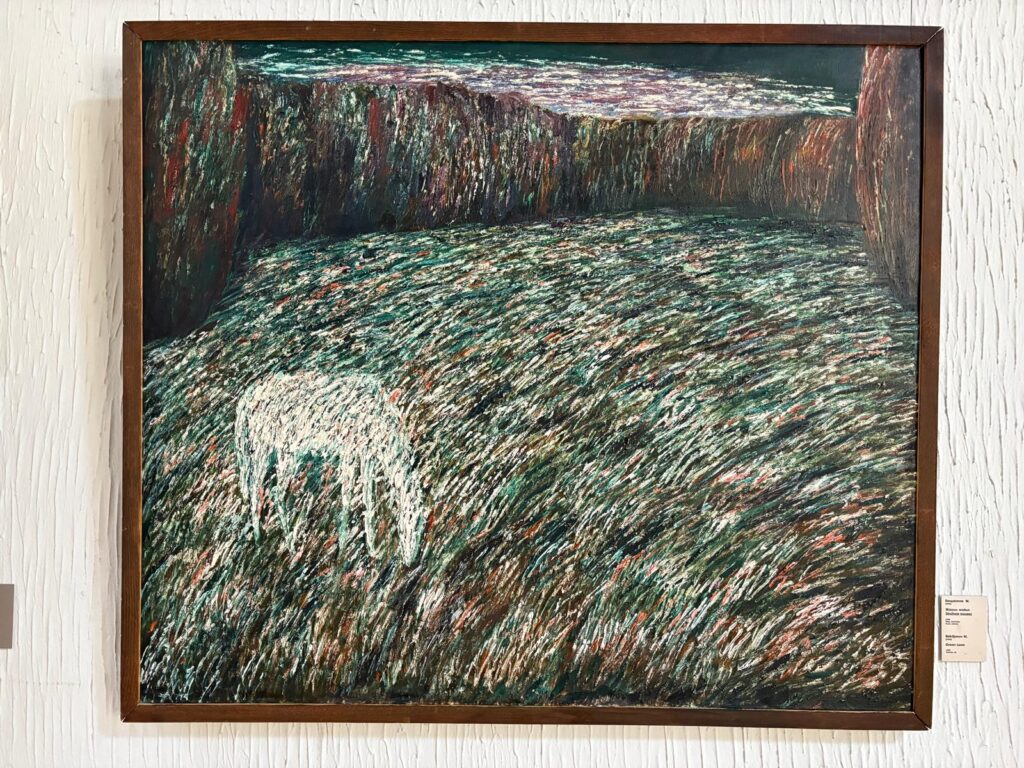

From the 1960s, the dominance of Socialist Realism as the only artistic style lessened across the Soviet Union. We see this change in the museum. Brushstrokes become looser. Sculptures are less realist, more idiosyncratic. Landscapes don’t need to be populated by rosy-cheeked peasants to have a purpose. Some works depict purely Kyrgyz themes like manashi, reciters of the Epic of Manas. The uniformity of the early Soviet period is no longer evident.

Classic Fine Art: the Origins of the Collection

The way the museum is laid out, most visitors seem to visit in the same order I did. Applied arts first, then working through the Soviet period, finally ending up in the section containing what I’m calling classic fine art. By this I mean probably some of the works that made up the initial collection: pre-Soviet Russian artists, primarily, in an academic style. There’s also, right at the end, a little section of plaster casts of ancient sculptures and works of art: Graeco-Roman, Babylonian, etc.

I don’t have anything against plaster casts and traditional works of art. But the thing is, after the freshness and interest of the preceding sections, it’s all just a bit… boring. It doesn’t help that all the works in this final section are fairly minor, not all in very good condition. Some canvases sag, mirroring my lack of enthusiasm as I looked around the portraits, landscapes and historical scenes.

In the context of this being a National Museum of Fine Arts, it makes sense. Where else would the people of Bishkek and Kyrgyzstan go to see older styles of art, if not here? But as a visitor, a cursory glance will do. I was so uninspired by this finishing point (a little bit on temporary exhibitions still to come), that I made my way back around the galleries I’d already visited, aiming to fill my mind with more distinctive images once more.

Final Thoughts (Before We Talk About Temporary Exhibitions)

If you’ve read this far, you’re probably not in much doubt about my views on the Kyrgyz National Museum of Fine Arts Gapara Aitieva. I hadn’t been sure about whether I would visit or not during my time in Bishkek. But I’m glad I did. I personally love a bit of Brutalist architecture, so enjoyed the building, for a start. And while the faded glory inside ticked some nostalgia boxes for me, I also liked what the museum seemed to have done within its means to refocus the collection somewhat to tell a story of continuity in Kyrgyz art. By the end of a visit it’s definitely the classical, Western-style art that seems out of place, not the shyrdaks and ala-kiyiz.

I said in my last post that the Kyrgyz National History Museum would be my pick if you only had time for one museum in Bishkek. Should I revise that now? I don’t think so, but I’d like to qualify my earlier position. I still think that, for most visitors, the National History Museum is the best bet. You get to learn about nomadic culture and the history of Kyrgyzstan from Russian Empire to Soviet Union to independent nation. Plus it’s well-presented and meets most people’s expectations of a modern museum.

If you’re a museologist or committed art lover, though, I think the National Museum of Fine Arts is a more interesting pick. And in the end, for me, that comes down to it being a Gesamtkunstwerk. The museum’s architecture, interior, collection and curation all come together to create an immersive experience that imparts a lot of information about art in Kyrgyzstan past and present.

Temporary Exhibitions

OK. Finally, I just wanted to say something about the museum’s temporary exhibitions before we finish. There were two when I visited (and a third display on the ground floor). You can see images of one in the first block of photos in this post, and images of the second immediately above.

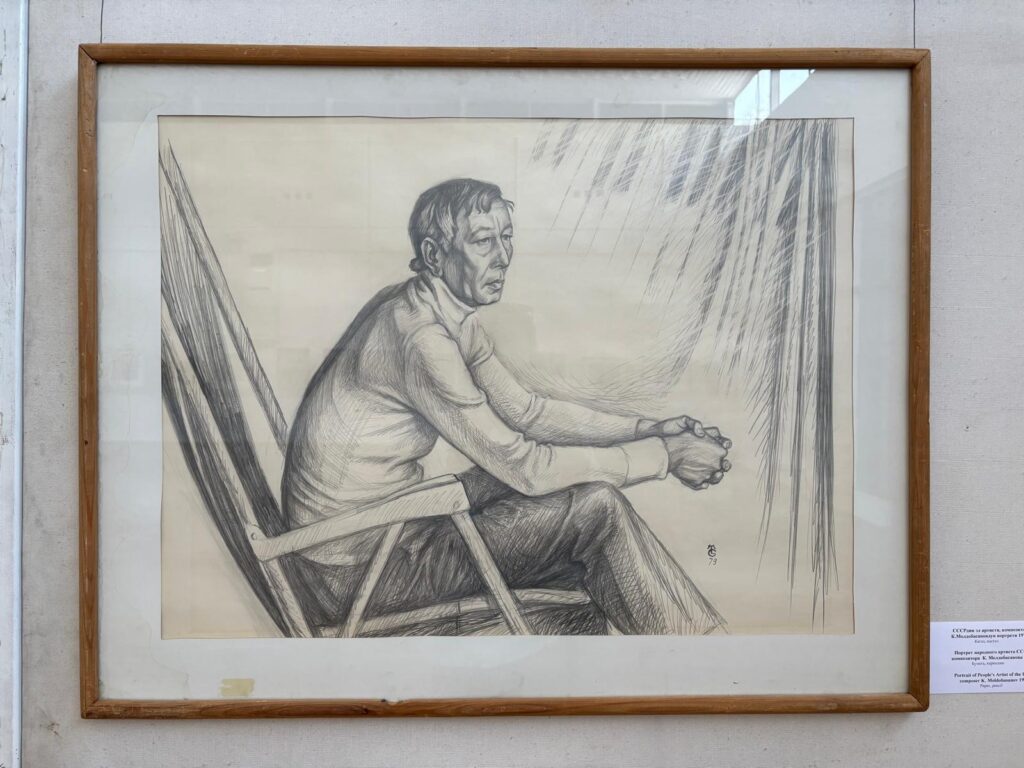

The first temporary exhibition was in what is clearly a dedicated space, a big and airy room just off the foyer. Around the perimeter were various works by Theodor Teodorovich Herzen, a Kyrgyz artist this time of German descent. 2025 was the 90th anniversary of his birth, and he died in 2003. The museum holds around 700 of his works, which are in various media: painting, prints, drawings, bas relief, mosaics. The selection here is primarily of graphic works.

In some ways it sets the scene for the museum visit to come: many works subscribe to a Socialist Realist style but nonetheless have distinctly Kyrgyz elements, whether that be the people, or retelling traditional stories. The museum, writing about the exhibition and the artist, say “His works are distinguished by their justice, honesty, deep interest in people and their native land.” I can’t find dates so it may already be finished, but it was a nice little presentation.

The second exhibition also marked a 90th anniversary. Traces of Time is/was a 90th anniversary exhibition for the museum itself. Again fairly small, it contained 41 works of decorative and applied art by Kyrgyz artists of different generations. I found it a good mirror to the transitional gallery between the applied arts and Socialist Realist collection. The artists here were even bolder in their choices, modernising traditional techniques, and injecting into them new forms and subject matter.

Over at the National History Museum, I noticed there was very little focus on temporary programming. One or two displays on posterboards and easels, but that was about it. At the National Museum of Fine Arts it’s a different story. Here the exhibitions invite visitors to discover new artists, bring in a more contemporary element, and support the museum’s overall curatorial focus on continuity in Kyrgyz art and contextualisation of the Soviet period. Don’t skip them if you visit.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.