Current Courtauld Exhibitions, Incl. Abstract Erotic (LAST CHANCE TO SEE)

Multiple exhibitions (including Abstract Erotic) at the Courtauld are an opportunity to explore, learn, and choose a favourite. Mine wasn’t quite what I had expected!

Four for the Price of One (Sort Of)

I really should be making more use of my Courtauld membership. I purchased one towards the end of last year because I’d left it too late to see sold-out exhibition Monet and London: Views of the Thames. Since then I saw Goya to Impressionism once or twice, and now Abstract Erotic. But I left both quite late in the run, and haven’t availed myself of any of the members’ early openings or anything like that. All in all, a cautionary tale where the moral is to keep on top of which exhibitions need to be booked in advance…

But since I have the membership, I am at least diligently going to each exhibition. And while I’m there, I normally like to go and see what else is on. There’s always something. In addition to the permanent collection, the Courtauld Gallery have two temporary exhibition spaces aside from the main one, and a gallery devoted to the Bloomsbury Group. They also have changing displays in a couple of places.

On this particular visit, that meant there were four exhibitions in total. And since I was a little underwhelmed by the headline exhibition (more on that momentarily), this post will be a round up of all of them. Enjoy, and let me know in the comments if you have a favourite.

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams

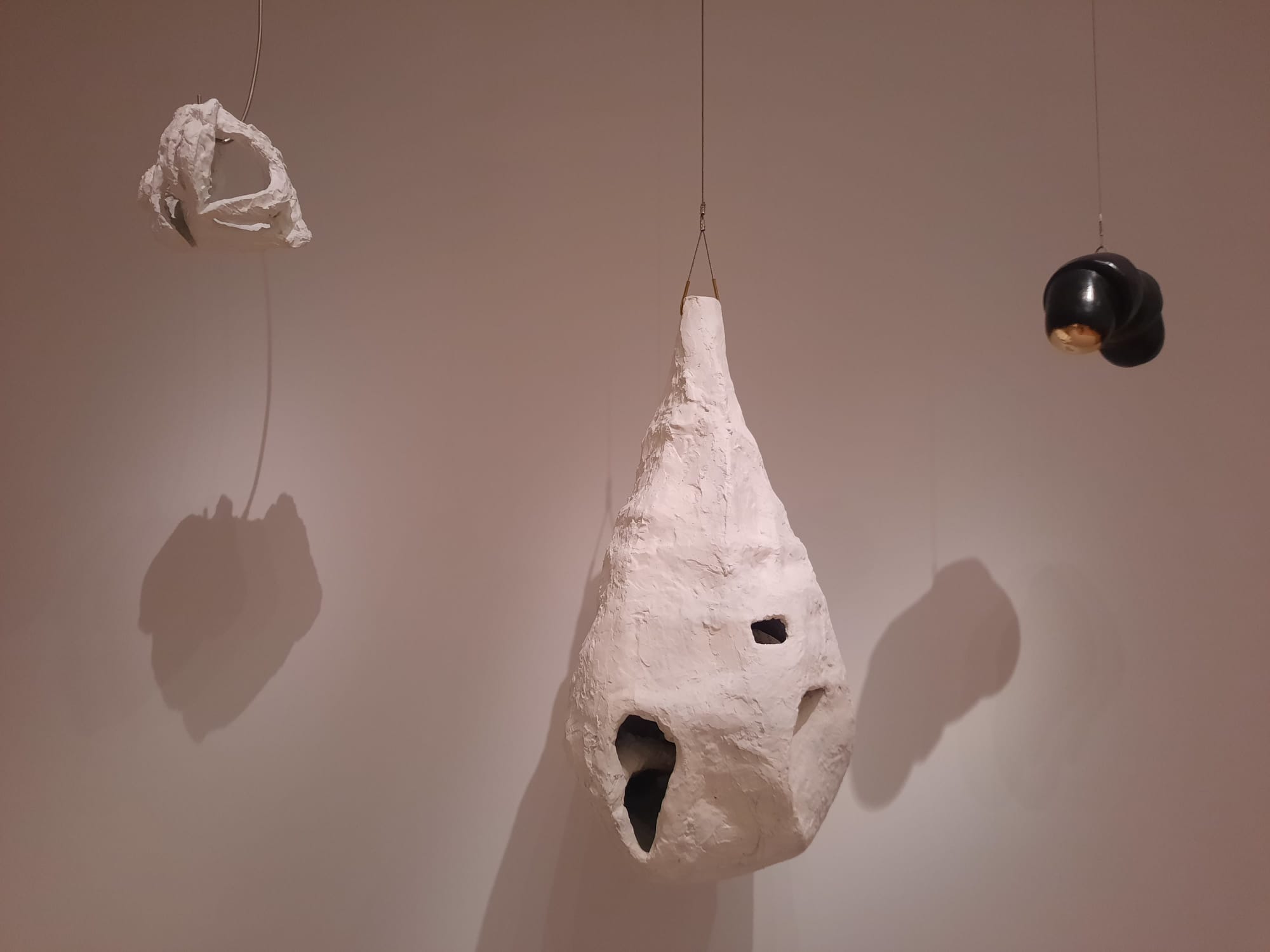

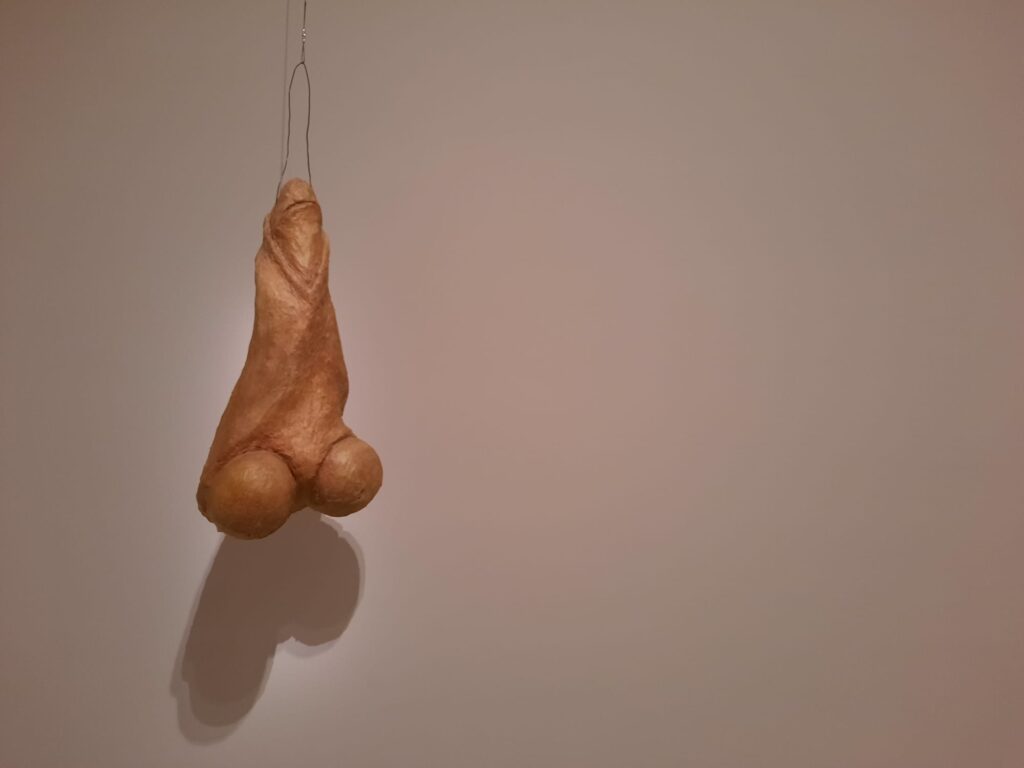

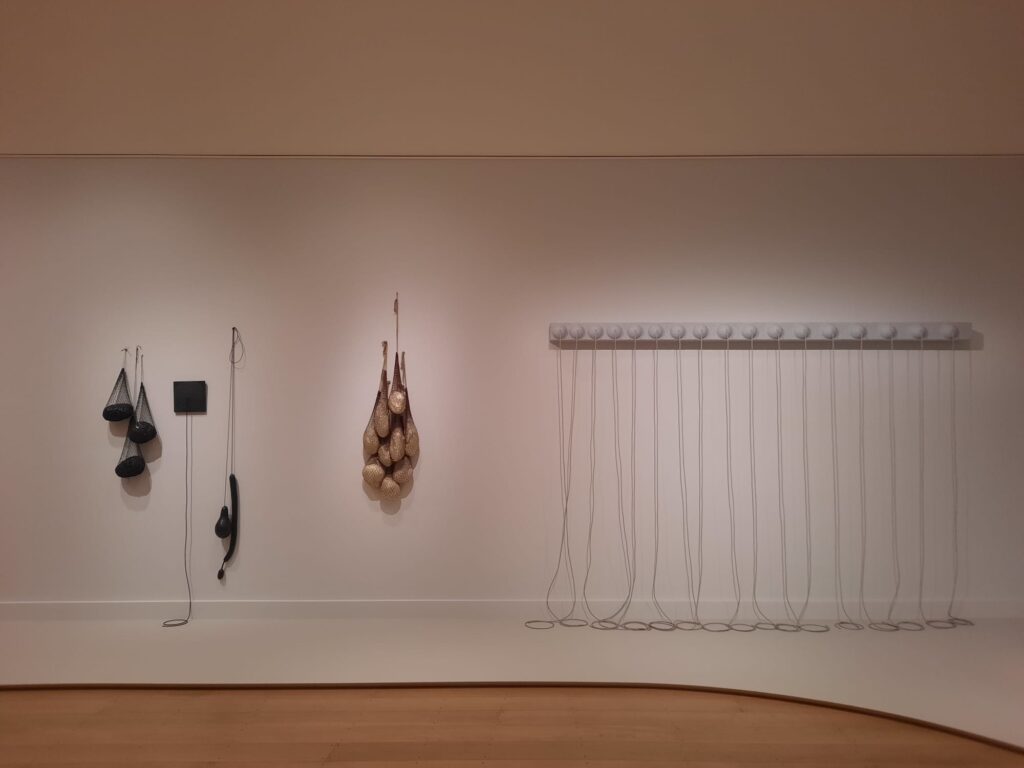

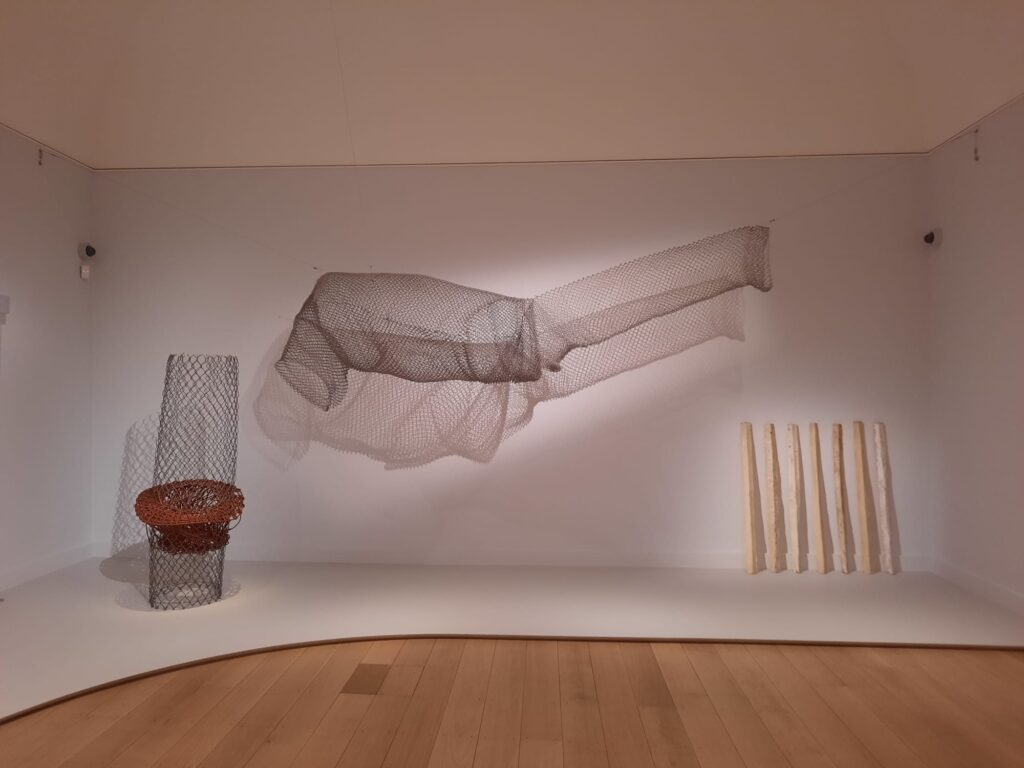

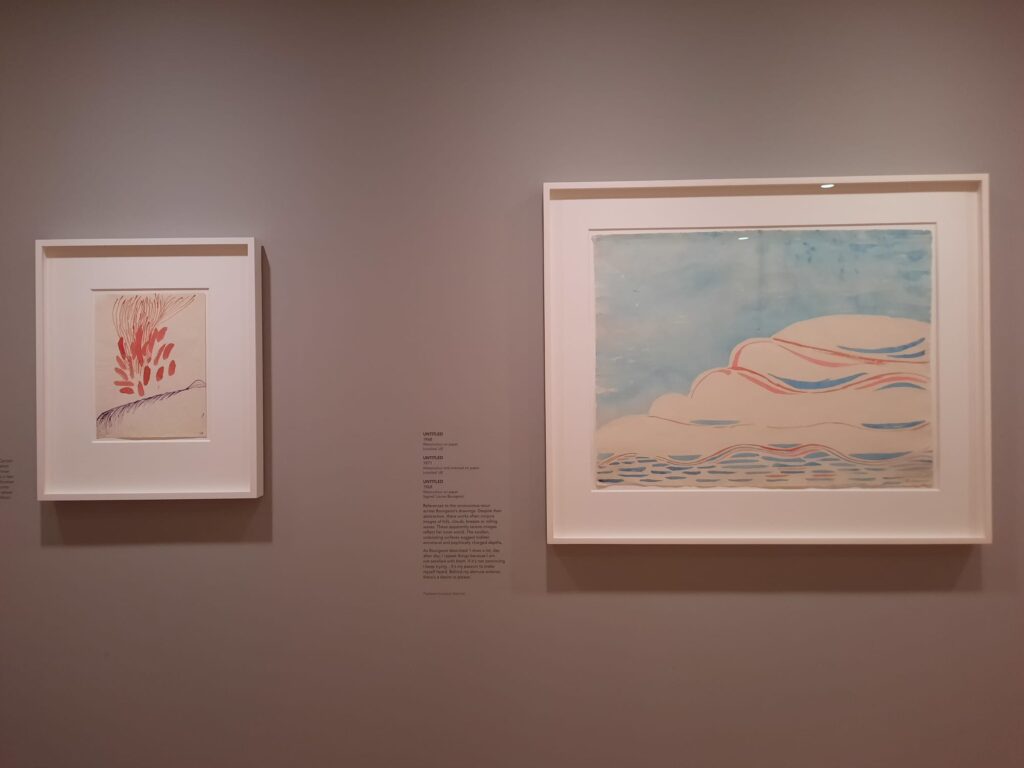

The somewhat underwhelming headline exhibition today is Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams. The title seemed a little strange to me, but not incongruous with what I knew already of Bourgeois’ work (I wasn’t as familiar with the other two). But it transpires the inspiration for the exhibition is a 1966 exhibition curated by art critic and feminist Lucy Lippard, which included all three women (and some men). Lippard coined the term ‘abstract erotic’, and noticed an emerging quality in the artists’ work, which approached abstraction and the human form from new angles. Reflecting later, Lippard realised what she was seeing but didn’t yet have the language for was ‘feminist art’.

A really interesting premise for an exhibition, in other words. But, as much as it pains me to say it, I don’t think the Courtauld was the right venue on this occasion. And the reason I say it is the quality I normally most love about the Courtauld’s exhibition space: its diminutive size. With some fairly large works on view (some smaller ones too), there’s enough space to introduce the idea and the artists. But then we’re through the two rooms already and that’s it. It feels like the preamble to a much larger exhibition; one which I would happily go and see one day.

There are nevertheless some insights into Bourgeois, Hesse, Adams and their work. Particularly their experimentation with materials. Latex was a new one at the time, and while the artists may not have anticipated how it would darken and harden over the years, it seems they all take it in stride as a manifestation of the ultimate ephemeral nature of art. There’s also a real sense of humour in some of the not-quite-abstracted body parts, or in Bourgeois casually calling a sculpture Tits. These are artists who were breaking new ground, whether in being included in group shows like Lippard’s, in exploring a female viewpoint through art, or in adopting non-traditional materials to execute their visions. I just wish it was bigger so the ideas could be further developed!

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Abstract Erotic: Louise Bourgeois, Eva Hesse, Alice Adams on until 14 September 2025. Additional charge to visit.

The Barber in London: Highlights from a Remarkable Collection

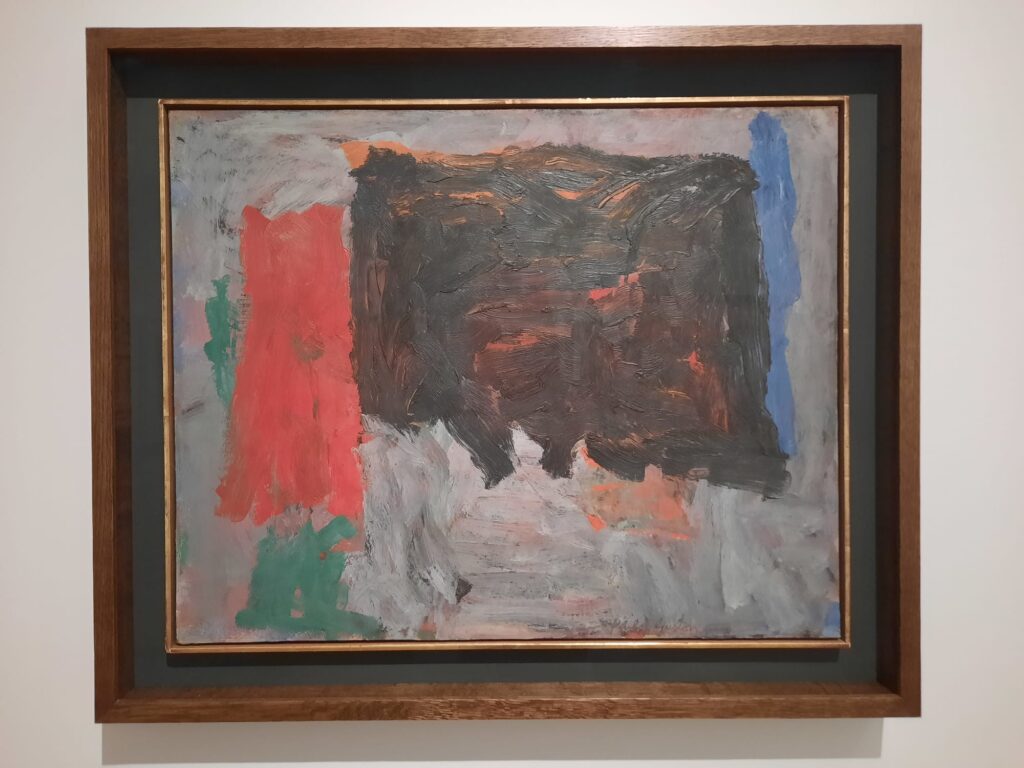

Interestingly, after complaining about a two room exhibition, this one room exhibition was my pick of the bunch. The Barber Institute in Birmingham isn’t huge, but it has a reputation for quality. It was founded in the 1930s by Lady Barber in memory of her husband, Sir Henry. Unlike Samuel Courtauld, who built his collection himself, she gave the money and left the decisions to professionals. Very different approaches, but both resulted in collections that are now cornerstones of the UK’s public galleries.

The Courtauld’s selection from the Barber makes that clear. Every painting here feels like a highlight. And it is: the Barber Institute is closed for renovations until 2026 so they have the pick of the bunch. The Vigée Le Brun portrait was my favourite: a great example of the artist’s stylish, confident work. I also enjoyed seeing Whistler and Hals again, represented by paintings I’ve come across in temporary exhibitions elsewhere.

What really makes it interesting is how it sits within the Courtauld’s wider programming. They are good at telling the story of how private collections became public institutions, and this show adds another chapter. Here they discuss the different collection-building methodologies, and how some of Lady Barber’s stipulations (like no 20th century art) have been relaxed over the years. They also build connections between the collections. Gainsborough took inspiration from a composition by Rubens, for instance, for the example of his work here on display. And by a bit of good luck, a preparatory drawing for the same is part of the Courtauld collection and on view downstairs. It’s a neat reminder that these collections don’t exist in isolation.

Close to a century now since these gifts, it’s a good reminder of how they came into being. And it’s nice that during the Barber Institute’s closure, Lady Barber’s memorial to her husband is being celebrated in London. The Courtauld deserves credit for continuing to shine a light on the different ways Britain’s museums came into being. And this is a great capsule collection of Western art.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

The Barber in London: Highlights from a Remarkable Collection on until 26 February 2026. Included in permanent collection ticket.

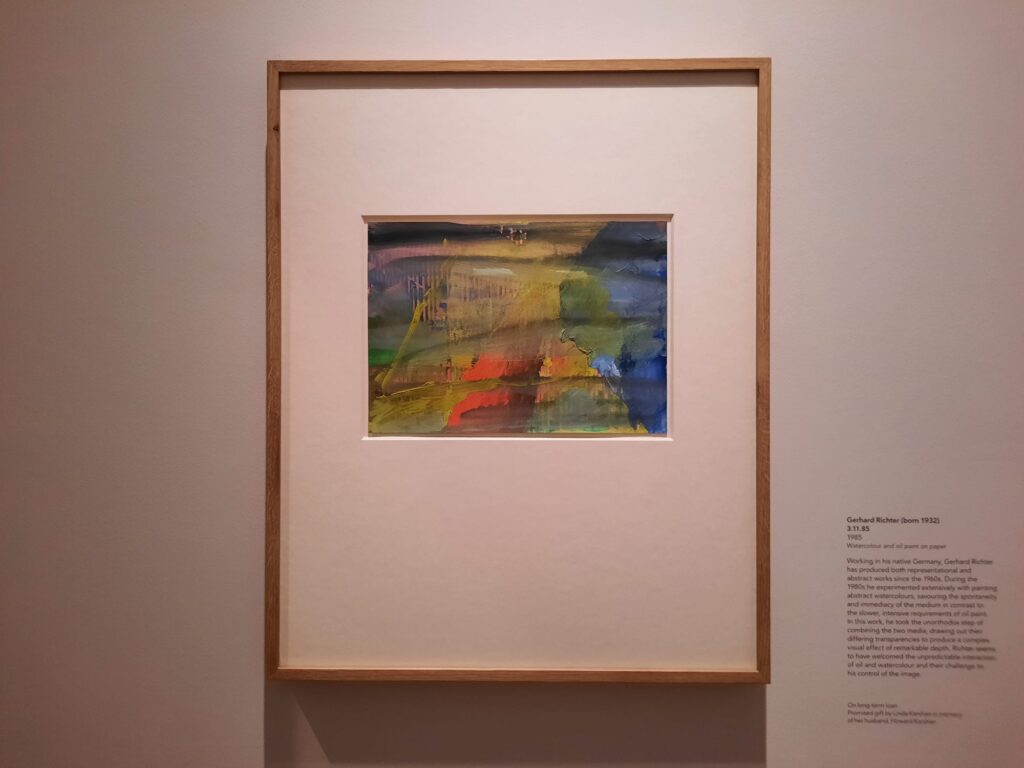

Post-War Abstraction: Works from The Courtauld

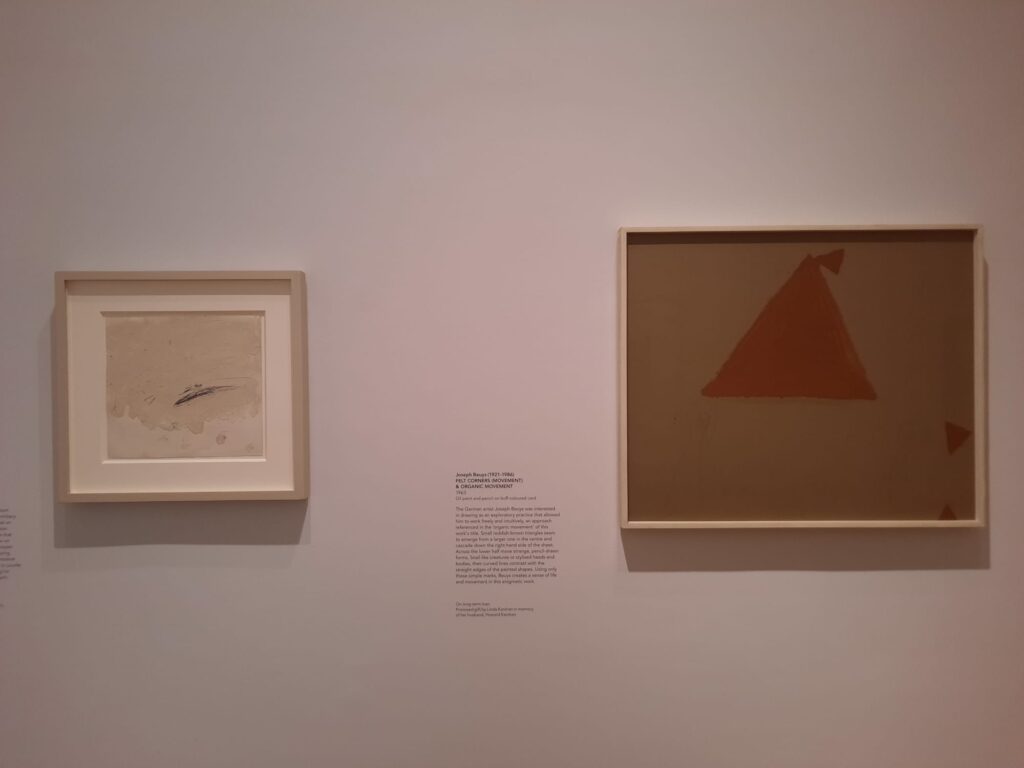

This one felt a bit like a companion piece to the headline exhibition upstairs. Not a showstopper in its own right, but something that adds useful context. And of course it’s a posthumous part of the Courtauld collection as far as Samuel Courtauld himself is concerned. He died in 1947, so we’re talking about acquisitions and gifts that came later. Mostly one gift in particular: the majority of the works come from a promised future gift and are currently long term loans.

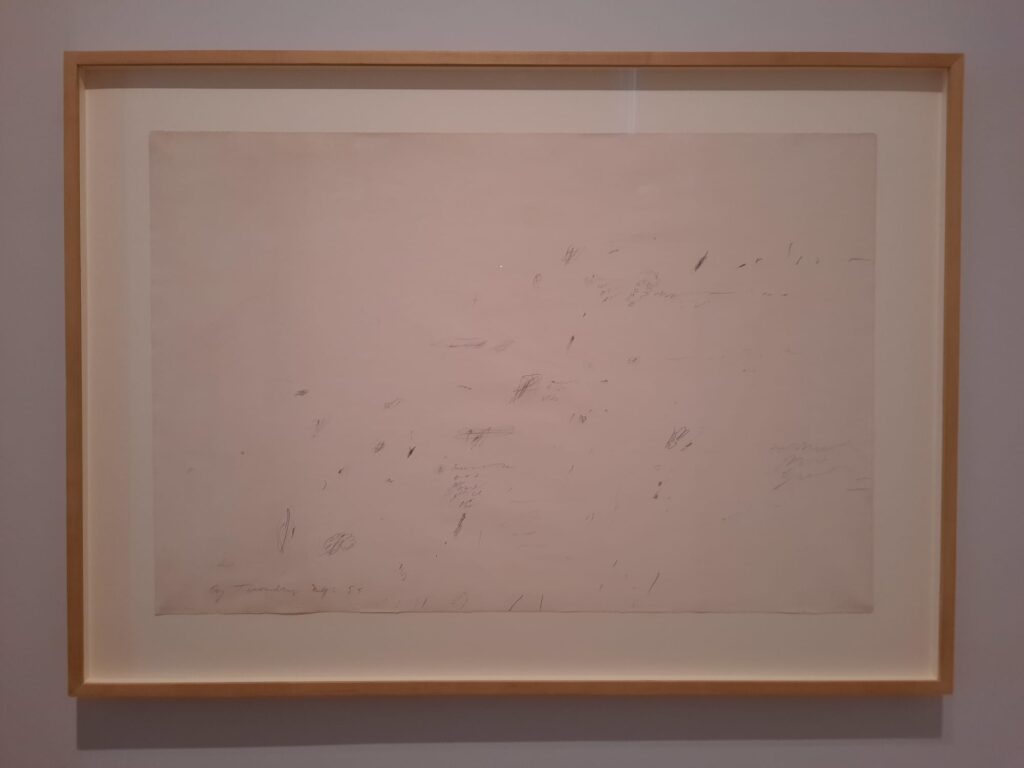

What’s on display are mostly works on paper, with a few monochromatic pieces. So don’t expect the energy of a Jackson Pollock or the kind of big, splashy canvases you might associate with post-war abstraction. But taken on their own terms, the works here are interesting examples of each artist. I particularly liked an experimental Richard Serra, where he tried working on layered plastic without knowing how the lithographic crayon would take. The result has an exploratory quality that I found compelling.

I’d describe the exhibition overall as more like a supporting essay in a catalogue than the main attraction. It opens up additional lines of thought, reminding you that abstraction didn’t take a single form after the war but branched out in quieter, more conceptual directions as well. And while it may not be the thing that gets you rushing to Somerset House, it does broaden the conversation.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Post-War Abstraction: Works from The Courtauld on until 12 October 2025. Included in permanent collection ticket.

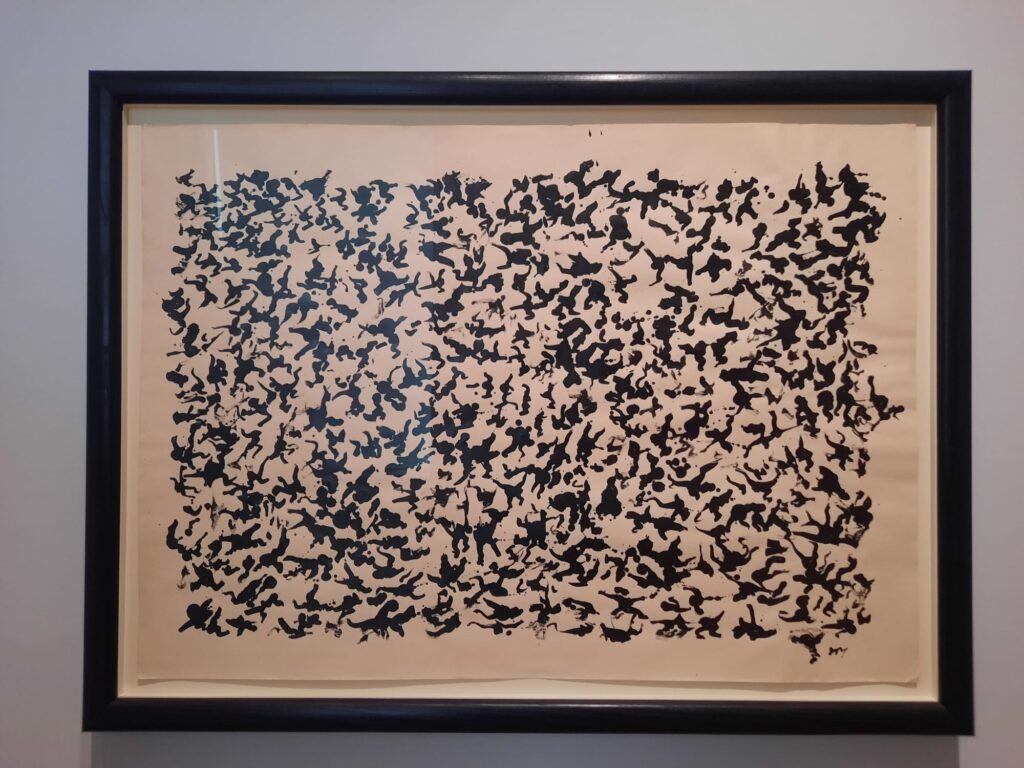

Louise Bourgeois: Drawings from the 1960s

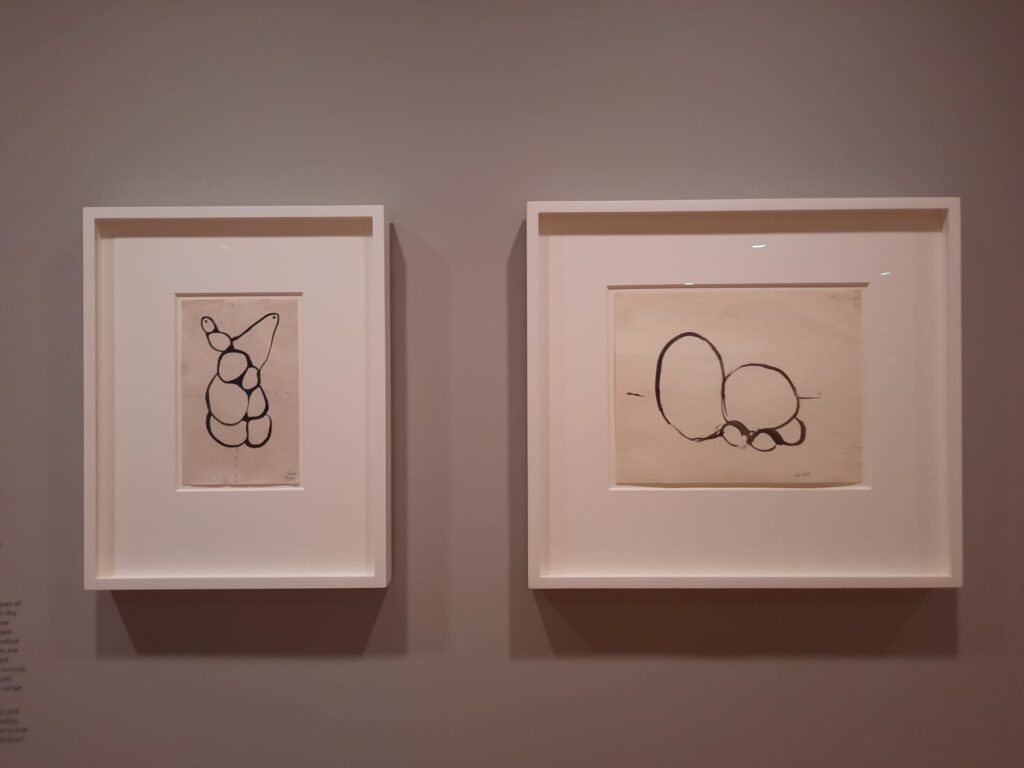

The Courtauld usually keeps one room aside for works on paper, and that’s where this small Bourgeois display is housed. Like Post-War Abstraction upstairs, it felt more like a catalogue essay than a full exhibition. But it’s a useful one, showing another side of Bourgeois’ multidisciplinary practice.

The drawings give a sense of how she worked through ideas, sometimes circling back to the same shapes and feelings again and again. That repetition ties in with what we saw upstairs in Abstract Erotic, particularly the influence of her psychotherapy, and the way she mined it over decades for artistic fuel.

Visually, these sheets aren’t the most striking things on view at the Courtauld right now. I found myself spending less time here than in the other rooms. But it was still interesting to consider Bourgeois from this angle, and to see abstraction take the form of thought sketches rather than sculptural drama.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 2.5/5

Louise Bourgeois: Drawings from the 1960s on until 14 September 2025. Included in permanent collection ticket.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.