Collection of the Russian Museum (Colección del Museo Ruso), Málaga

The Colección del Museo Ruso is a fascinating case study in what to do when geopolitics get in the way of your museum’s purpose. Oh, and the exhibitions are pretty good, too.

Introducing the Colección del Museo Ruso

In my last post, we did a walking tour of the working class Málaga neighbourhood of Huelin. As part of that, I showed you the Tabacalera. It’s a 1920s tobacco factory that was in use until the early 2000s, and has since been repurposed as a home for several municipal and cultural institutions.

I came to Huelin on my last day in Málaga for a few reasons. With a morning to kill before going to the airport, I wanted to stretch my legs. I was interested in this purpose-built neighbourhood, the kind of paternalistic industrialism that was common in the 19th century. But I also really wanted to see the Colección del Museo Ruso, or the Collection of the Russian Museum.

It was the name that first caught my eye when I was looking for things to do in Málaga. The Collection of the Russian Museum. So it’s not a Russian museum, it’s the collection thereof? What does that mean? Why is there a Russian museum (or collection) in the South of Spain? My curiosity as a museologist was piqued.

Even more so when I understood a bit more about the museum. Because, you see, this is (or was?) an outpost museum. An outpost of a Russian museum, which opened in 2017. Not long before war broke out between Russia and Ukraine, and collaborations and connections with Russia became a lot more difficult. I really wanted to see how the museum had responded to these challenges, so my plan for my last day was set. Huelin and the Colección del Museo Ruso it was.

Satellite Museums: A Quick Detour

Satellite museums are something I find rather interesting. Several big institutions have gone down this route. You might have heard of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, for instance. Or even Tate Liverpool on a more domestic scale. They were very much a topic of discussion back when I was studying museology. They have often been used as tools for regeneration: the Guggenheim Bilbao, for instance, is an iconic venue and tourist draw for a historically industrial city in Northern Spain. For the institutions, satellites are a way to extend their brand and influence, and also put more of their collection on display. That being said, they sometimes feel like a sort of museum colonialism, planting a flag on foreign soil. And increasingly, as geopolitics shift to become more nationalist and protectionist, they feel like one of the last throes of globalisation and optimistic internationalism.

The Colección del Museo Ruso is not Russia’s only satellite museum, nor is it Málaga’s. On the latter point, see, for instance, their branch of the Centre Pompidou. But it’s this question of Russian museum outposts that interests me, and what happens when things change. One other example gives us one model.

The Hermitage has been the main source of Russian satellite museums. I visited the Hermitage Amsterdam, which opened in 2009, when I lived in Amsterdam and thereafter. It was a great opportunity to see some pretty famous paintings from the Hermitage collection. After the outbreak of war between Russia and Ukraine, it only took a week for this institution to take decisive action. They severed ties with the Hermitage, taking an approx. €2 million hit on the exhibition then in flight. They have rebranded as H’Art, with new partnerships with the Smithsonian (not sure how that’s going now), the British Museum, and the Centre Pompidou. I haven’t been able to find out if the Hermitage Italy venture is still going or not.

But the situation is a little different with the Colección del Museo Ruso, which opened in 2017. It was the first European outpost of the Russian State Museum in St Petersburg. Their approach seems to be more about biding their time. The branding is a little vaguer, no longer the Russian Museum Collection, St. Petersburg-Málaga. And they are not currently loaning work from the Russian State Museum: what they did have when war broke out had to go back, prompting the early closure of four exhibitions. But it hasn’t yet prompted the closure of the museum itself. The Colección del Museo Ruso have instead leaned on private collections of Russian art and on Russian themes. They started using these collections to keep the doors open shortly after suspending ties with the Russian State Museum, and continue doing so to this day.

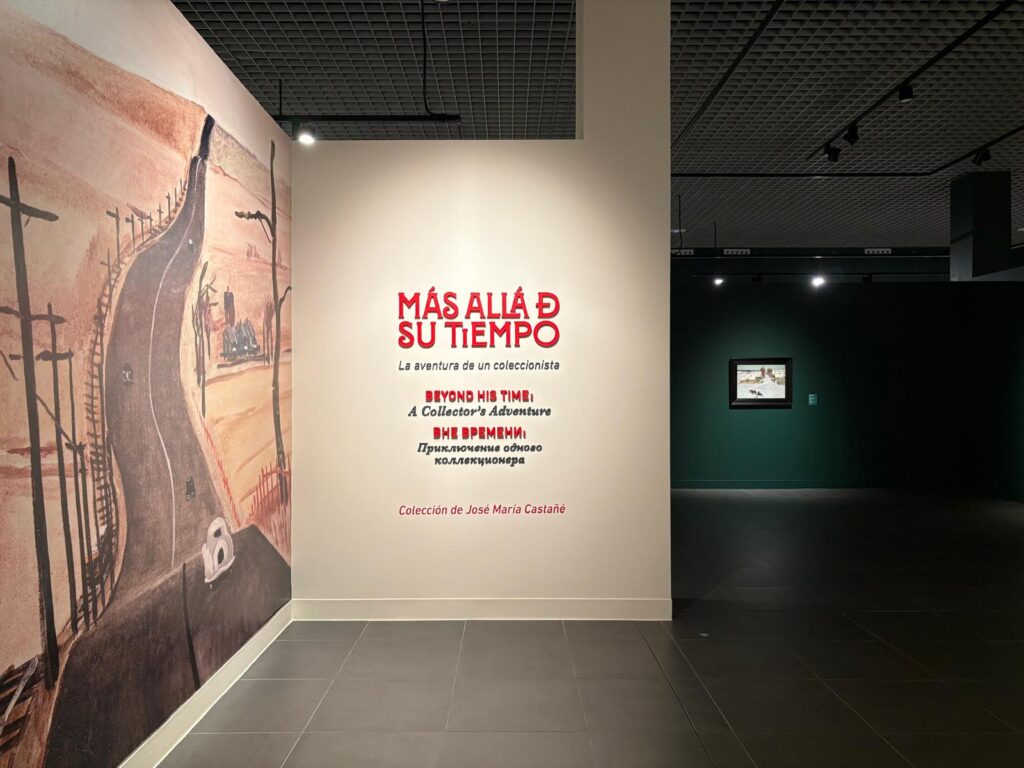

On View: Más allá de su tiempo

The decision to keep the focus on Russian art and culture is an interesting one. While the Hermitage Amsterdam felt the moral choice was to sever ties and shift focus, it seems the Colección del Museo Ruso take the view that the situation will improve eventually, and in the meantime there is a value to promoting mutual understanding and appreciation, at least from a cultural perspective. The aim of the museum in its original iteration was to turn “the museum’s branch in Malaga into a genuine window onto the cultural soul of Russia”. That seems to still be the case, with temporary exhibitions still Russian-themed. I’m not sure if there’s been any criticism of this locally or internationally: I didn’t extend my research in this direction.

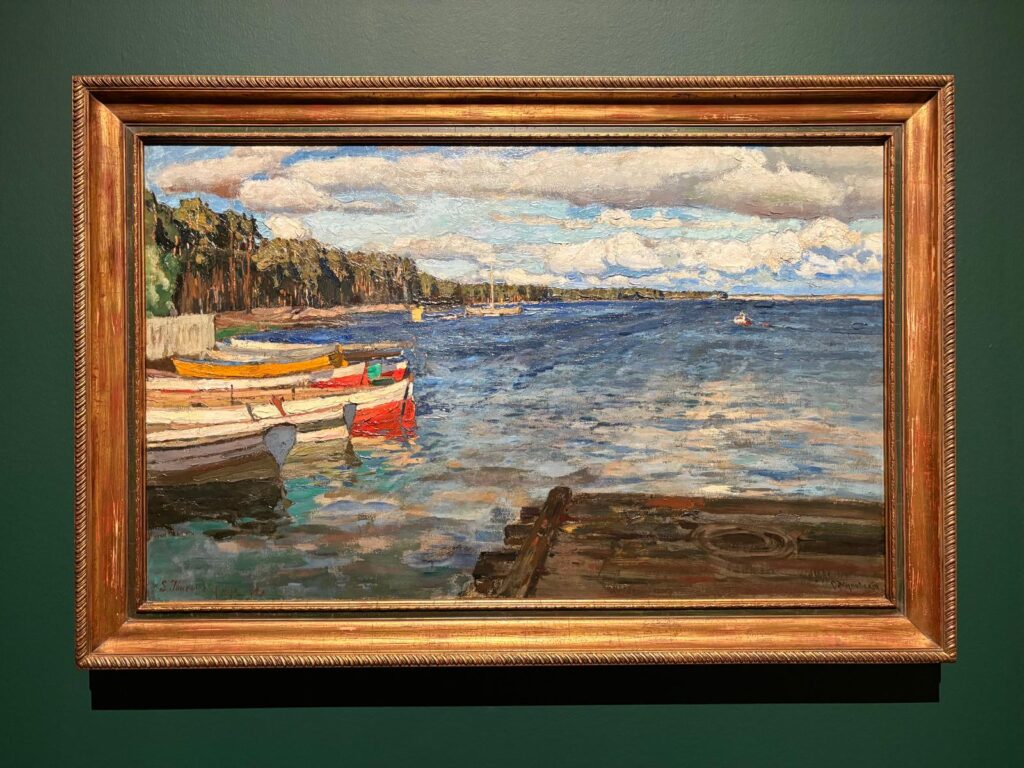

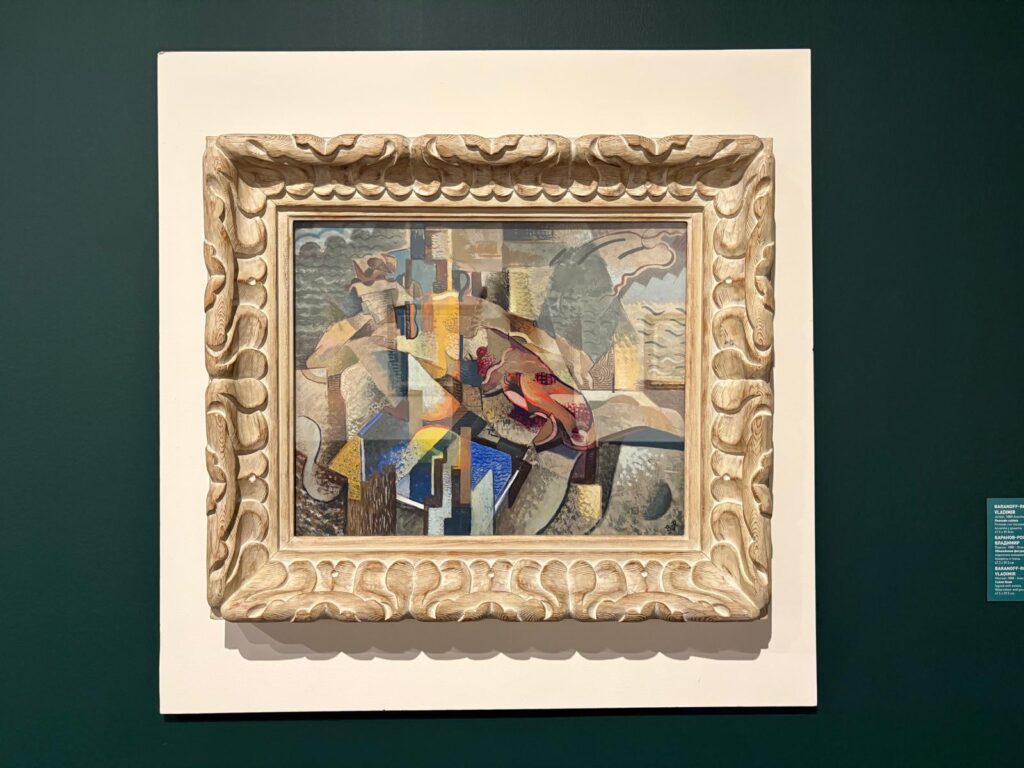

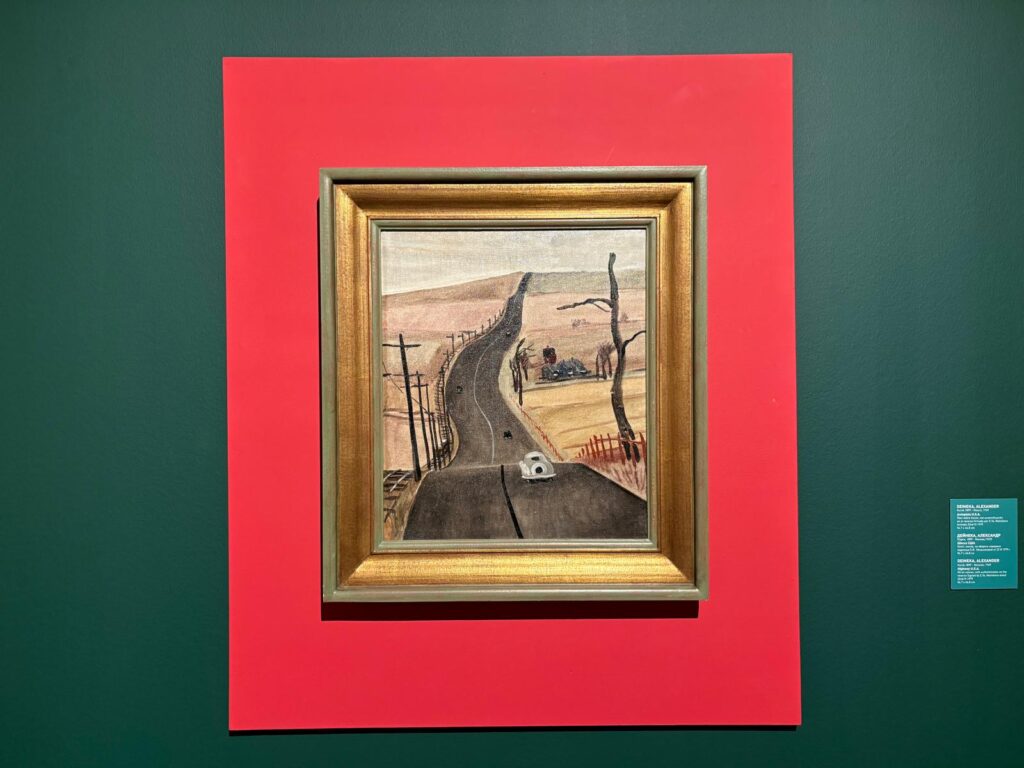

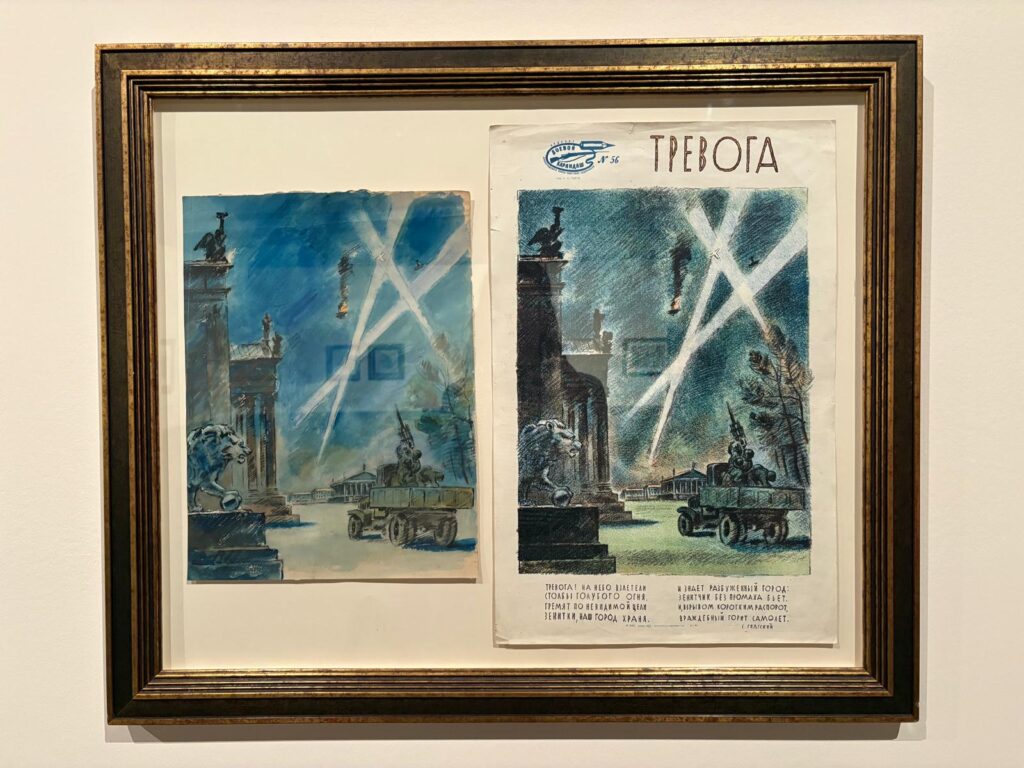

When I visited, there were several exhibitions to see. The primary one was Más allá de su tiempo: la aventura de un coleccionista (Beyond His Time: A Collector’s Adventure), ongoing since 2023 and without a current end date. This exhibition presents a selection of the Russian works collected by José María Castañé, a Spanish entrepreneur whose private cultural foundation has made a significant donation of materials to Harvard. This exhibition consists primarily of paintings and works on paper, with an avant-garde focus, mostly dating from the late 19th century to the end of WWII.

There are a few familiar names (like Lyubov Popova) and notable works (like Vladimir Baranoff-Rossiné’s Cubist Nude). But what I liked about it, if this doesn’t sound too patronising, is that it’s a good collection rather than an exceptional collection. It’s interesting to see a Spanish collection of Russian art, and to ponder whether that combination of cultures has had a bearing on the end result. And I get the feeling this collection and collector may not have sought the limelight were there not a need for just this type of art to go on view here.

A note: the images and text are not quite in sync for today’s post. You can see Castañé’s collection in the remaining blocks of images below.

On View: Additional Exhibitions

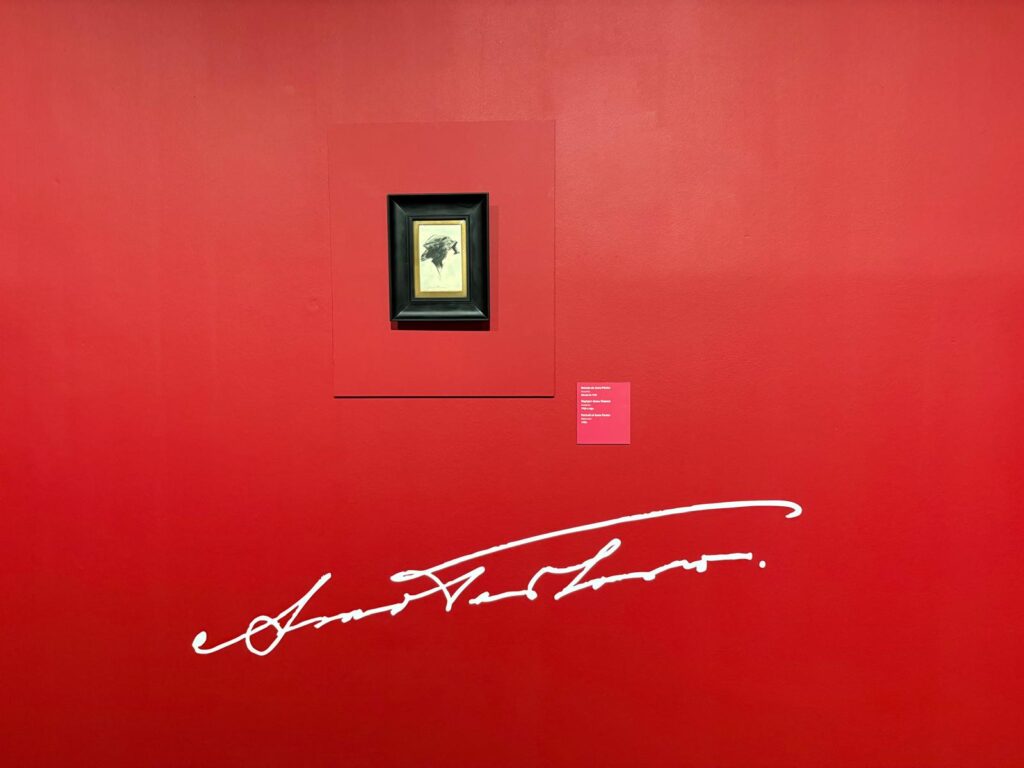

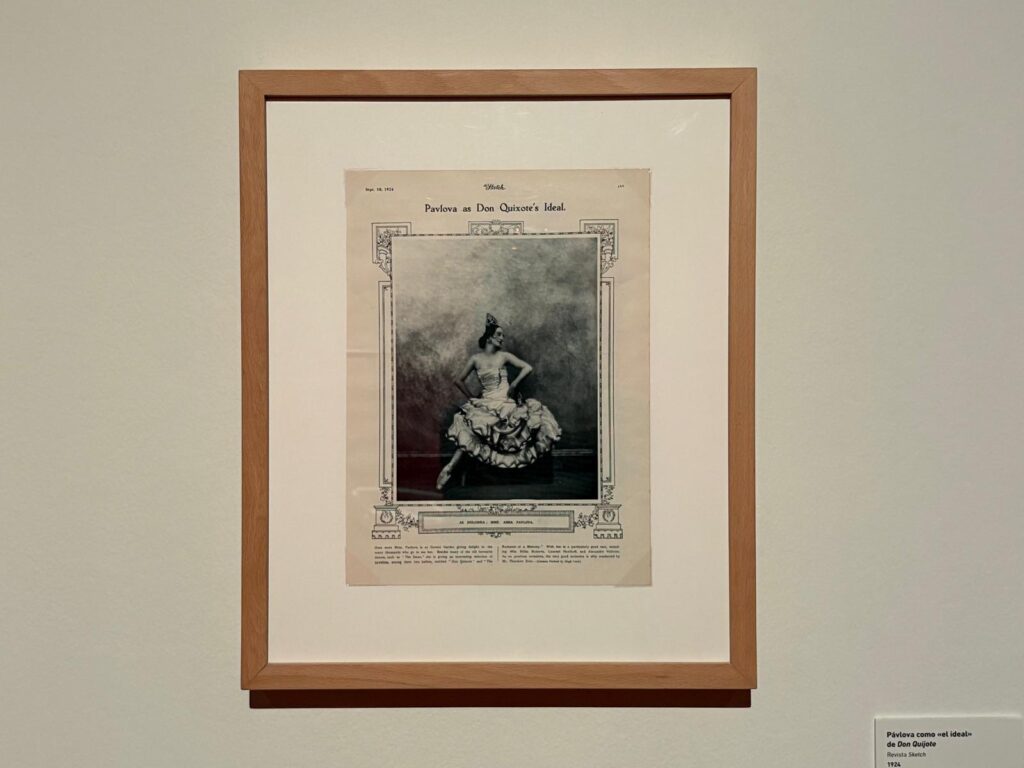

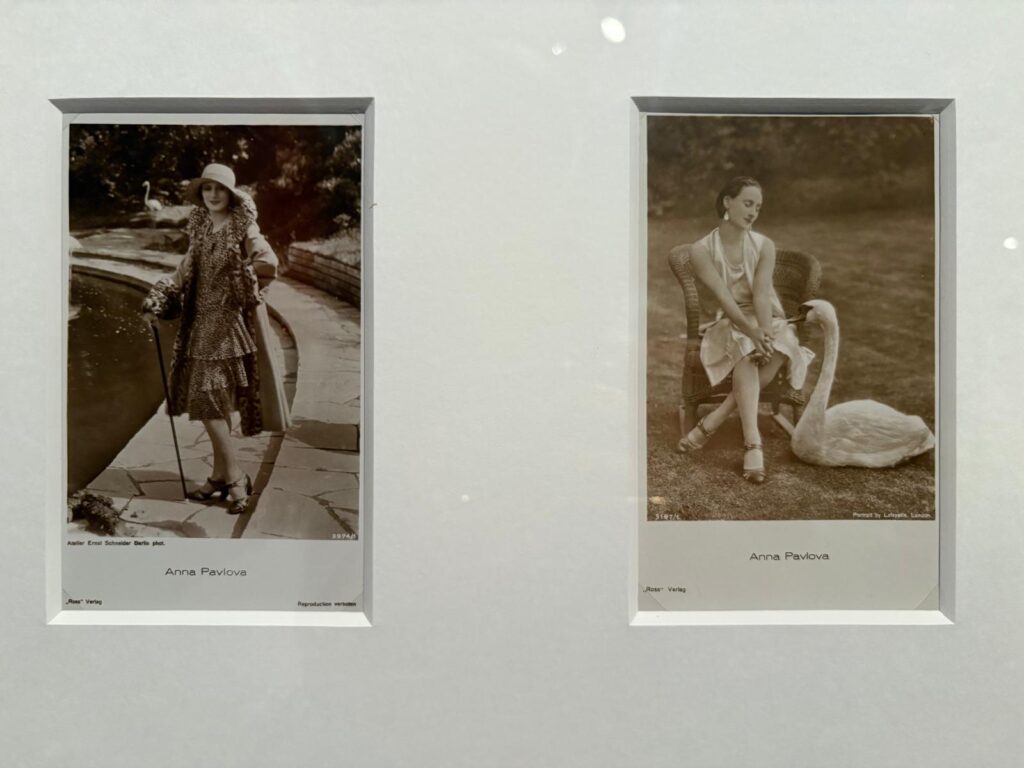

Más allá de su tiempo was not the only exhibition on view when I visited. The next biggest, and the first one I encountered (so images are above) was Anna Pavlova: una vida sin fronteras (Anna Pavlova: a Life Without Borders). This was primarily an archival exhibition, with images and souvenirs from her extensive performances and tours. In case you’re not aware, Pavlova (1881–1931) was one of the most influential figures in ballet. Technically skilled and expressive, her fame was amplified as it came about alongside new media like film. She worked very hard to maintain this reputation and toured extensively. Her tour to Australia and New Zealand in 1926 spawned a rivalry over the origins of the pavlova dessert which is ongoing a century later.

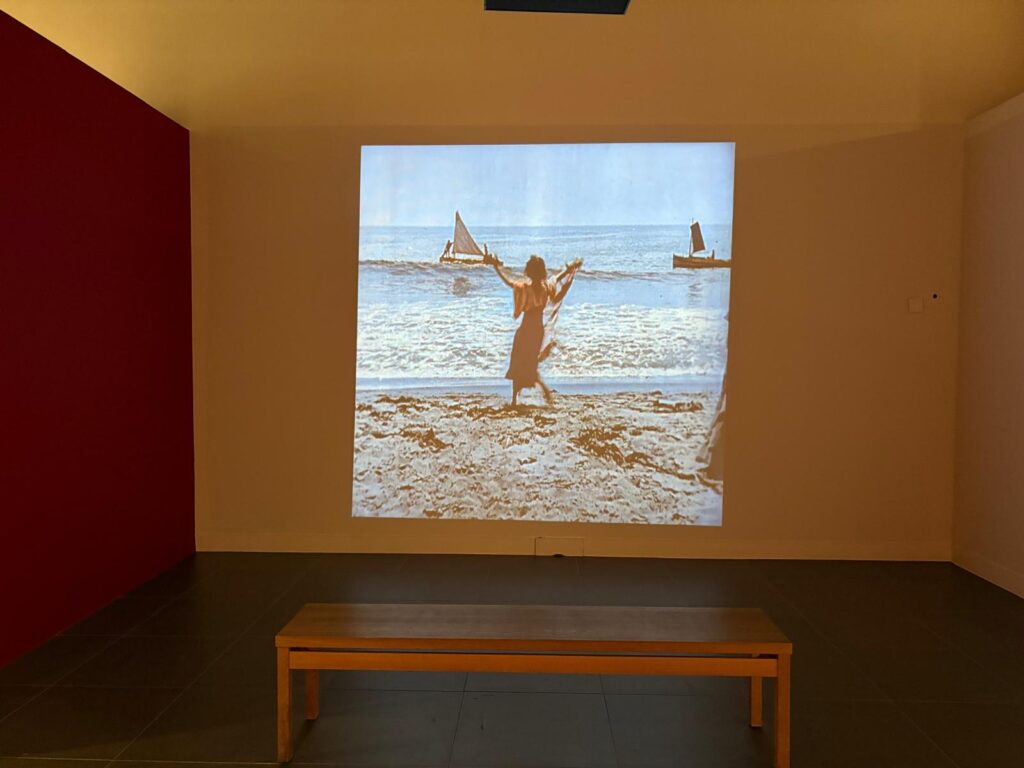

Pavlova is an interesting subject for an exhibition. Looking back, we can see a nascent celebrity culture and the creation of Pavlova’s ‘brand’. This even included a pet swan, tying back to her most famous role. A couple of film clips help to liven up an otherwise static and black and white exhibition. But I did enjoy it – the selection of objects is interesting, and the explanations brief but engaging. The exhibition continues until May 2026.

The other two exhibitions I won’t spend as much time on. They are smaller, for one, and not the main draws. First up is Boris Groys: pensando en bucle (Boris Groys: Thinking in Loop). Groys is an East Berlin-born artist and academic of Russian heritage. Compelled to emigrate from the USSR to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1981, he now lives and works in New York. Thinking in Loop consists of three videos on iconoclasm, ritual and immortality. This is another exhibition on since 2023 and without a planned end date at the current time.

Finally, there is Hidden Jungle by Chen Chenmu. This exhibition of paintings takes place across three sites. The Colección del Museo Ruso is here working in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou Málaga and the Picasso Birthplace Museum.* I quite liked the paintings, but was more interested in what I could glean from them about this museum’s place in the wider Málaga cultural landscape.

*As an aside, I think the collaboration extends beyond this exhibition. I noticed, for instance, that staff at the Colección del Museo Ruso wore Centre Pompidou uniforms. Perhaps this is another way to preserve resources and keep going during a difficult time.

Final Thoughts

I’ve described the exhibitions on view when I visited the Colección del Museo Ruso, but not so much the visitor experience. My overall summary is that you can tell things are not quite going as planned. For a start, before selling me a ticket, the staff carefully checked I was in the right place. When I headed upstairs to start my visit, visitor hosts explained that not all areas were in use. And you can feel the gaps. In some places you pass by unused galleries, surplus to current requirements. Elsewhere, a seating area between exhibitions felt like a not-entirely-successful attempt to fill the space with something. Creating temporary exhibition programming from private collections has kept the doors open. But it’s probably not sustainable indefinitely.

I will be interested to see what the future brings for the Colección del Museo Ruso. It doesn’t seem Russia is coming in from the cold any time soon. Meaning this museum will not be able to resume its function as a satellite of the Russian State Museum. Will other satellites go this way? To come back to something I alluded to earlier, things are difficult at the moment in the American museum sector. Will that Smithsonian partnership with H’Art last in that context?

So perhaps the Russian satellite museums are simply the first in a new trend: the shrinking of global museum footprints as we go through a period of fractious international relations. Only time will tell. But I continue to find museums such as this an interesting barometer of wider forces.

For visitors, the Colección del Museo Ruso is probably best for those with an interest in Russian culture. Or possibly those who want a quick museum experience in Huelin. I’m just going out on a limb here but I’m going to guess there’s more to cover at the Automobile and Fashion Museum also at La Tabacalera. Perhaps I’m just having flashbacks to the joint-focus National Transport & Toy Museum in Wānaka, New Zealand. But in any case I’m glad I visited – my museological interest on this occasion took me to a part of Málaga I wouldn’t otherwise have explored, and introduced me to new and engaging topics.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.