Colour, Form and Composition: Milton Avery and His Enduring Influence on Contemporary Painting – Malta International Contemporary Art Space (MICAS)

Visiting MICAS in Malta, I found myself unexpectedly reunited with Milton Avery’s paintings, in a space where history, architecture and contemporary art unite.

Revisiting Milton Avery

The last time (and possibly the first time) I spent real time with Milton Avery’s work was at Milton Avery: American Colourist at the Royal Academy in 2022. That exhibition made a clear case: Avery is an important artist because of his handling of colour. I remember walking through the galleries and being struck by the simplicity of the paintings, with their intuitive, rather than literal, palettes. The show itself was well put together, with a chronological flow that nonetheless allowed the colours to take centre stage. That framing, and the simplicity of Avery’s compositions, are what stayed with me most from the Royal Academy exhibition.

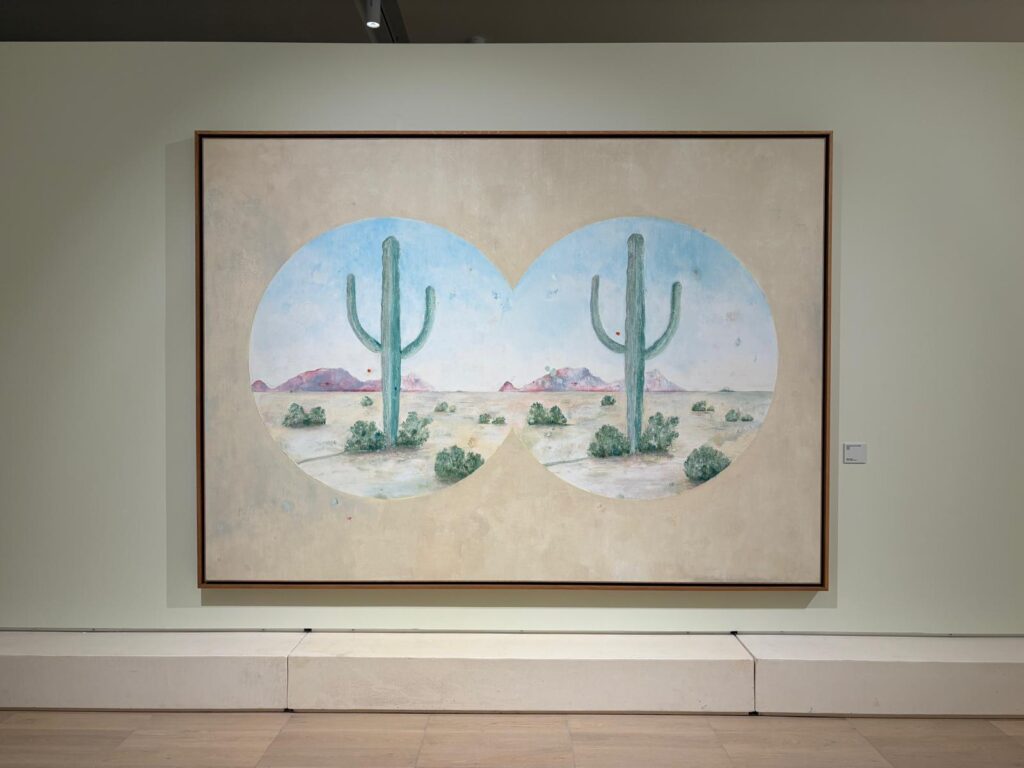

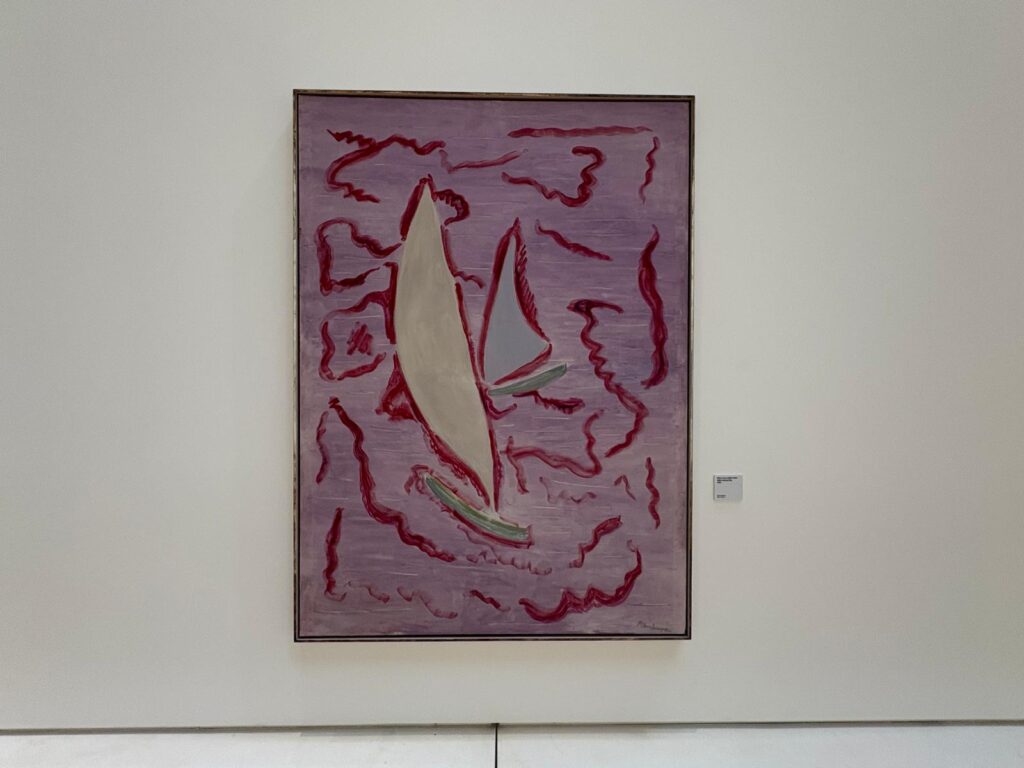

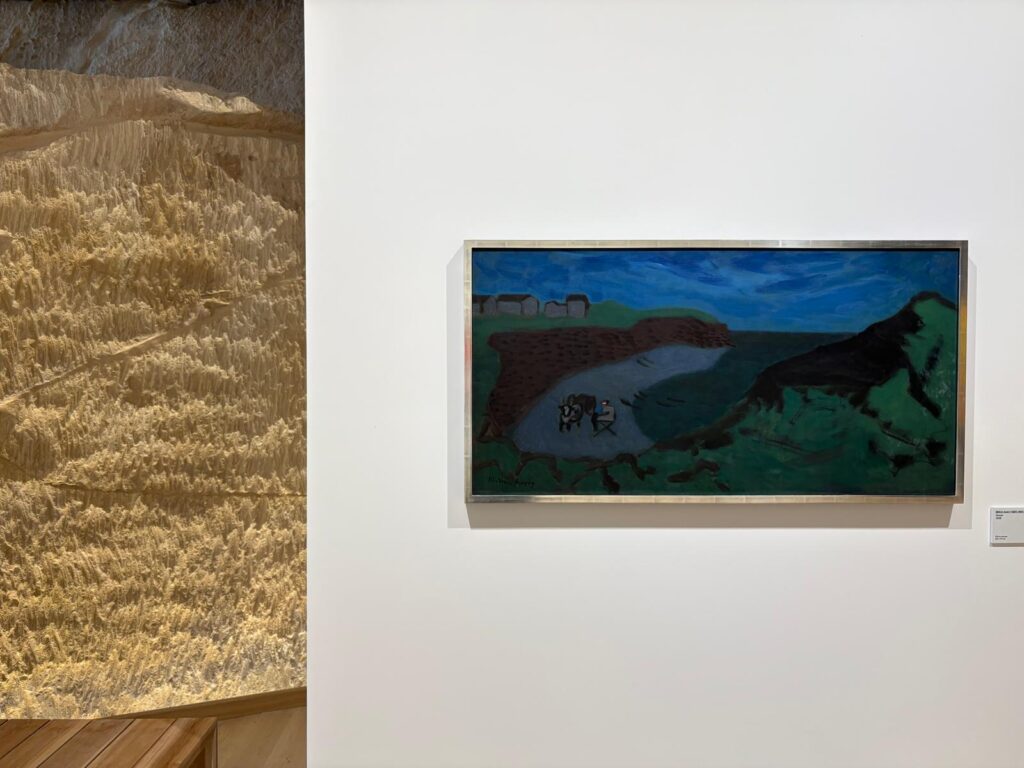

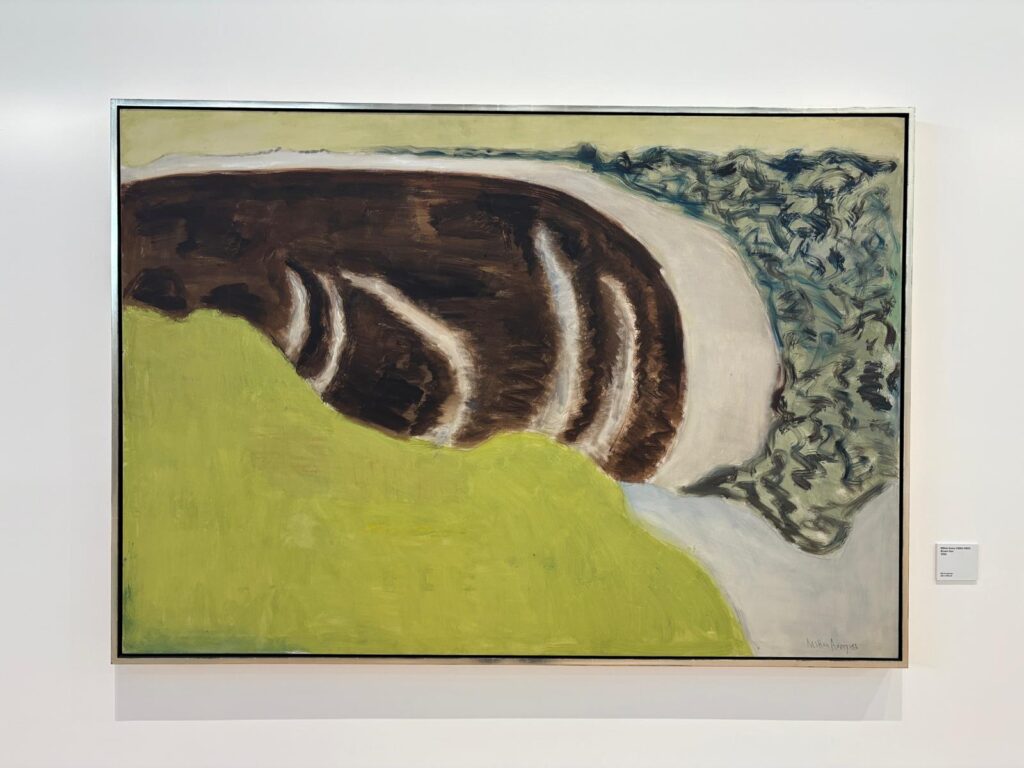

At MICAS (Malta International Contemporary Art Space), Colour, Form and Composition: Milton Avery and His Enduring Influence on Contemporary Painting marks my second encounter with Avery, but the emphasis is different. This time, colour shares the spotlight with shape and structure. Across more than thirty paintings and watercolours, the exhibition shows how central simplification and form were to Avery’s practice. Early, European-influenced landscapes sit alongside later works that edge towards abstraction. Alongside these are works by artists including Henni Alftan, March Avery, Harold Ancart, Andrew Cranston, Gary Hume, Nicolas Party and Jonas Wood, making visible Avery’s influence across generations.

What struck me walking through MICAS was how Avery’s decisions seem to open doors for others. Not just in colour, but in how forms are used to balance and push against one another. This exhibition, still a relatively rare chance to see Avery’s work at this scale, broadens the conversation around his legacy. Seeing some paintings again made me think less about mood alone, and more about how Avery understood relationships in paint, between colours, shapes and space.

Hello Old Friends

I felt an immediate sense of familiarity when I walked into MICAS and recognised paintings I’d seen before. I hadn’t come to Malta expecting to see this exhibition, so encountering Avery’s work here felt like bumping into an old friend in an unexpected place. That recognition made the exhibition feel personal straight away. In my 2022 review of the Royal Academy show, I’d even urged readers to make the effort to see it, aware that chances to see Avery’s work at that scale don’t come around often in this part of the world.

It was also interesting to notice how much the setting changed my response. In London, Avery’s paintings had been framed by a large, authoritative institution and a very clear curatorial argument. At MICAS, they felt looser, and less contained. Warm Mediterranean light filtered into the galleries, and the colours, even the subtle ones, felt different as a result. It was as if the works were adjusting to their surroundings.

I found myself lingering in front of certain canvases simply because I enjoyed them, rather than out of any sense of duty to their place in art history. I recognised familiar shapes, then started looking for differences. Then I noticed how contemporary artists, some born long after Avery’s death, had absorbed and reshaped aspects of his visual language. Seeing those connections play out helped me notice things in the older artist’s work that I’d missed before.

That mix of familiarity and discovery made the exhibition richer for me. It was a reminder that with art, one encounter is rarely enough. It’s the return visits (planned or accidental) that allow you to see more. Finding myself at a second Milton Avery exhibition, unexpectedly and far from home, was a rare gift.

Colour, Form and Composition: Milton Avery and His Enduring Influence on Contemporary Painting

Walking through Colour, Form and Composition, it quickly becomes clear how carefully MICAS has set up the conversation between Avery and the artists influenced by him. Rather than separating the historical work from the contemporary responses, the exhibition places them side by side. The influence shows up in different ways: shared palettes, flattened perspectives, or simplified forms. Sometimes the connection is obvious. Other times it’s more subtle. Seeing the works together helps those relationships surface. The hanging highlights lineage without spelling it out too neatly (although it’s worth noting that one of the artists included, March Avery, is Milton Avery’s daughter).

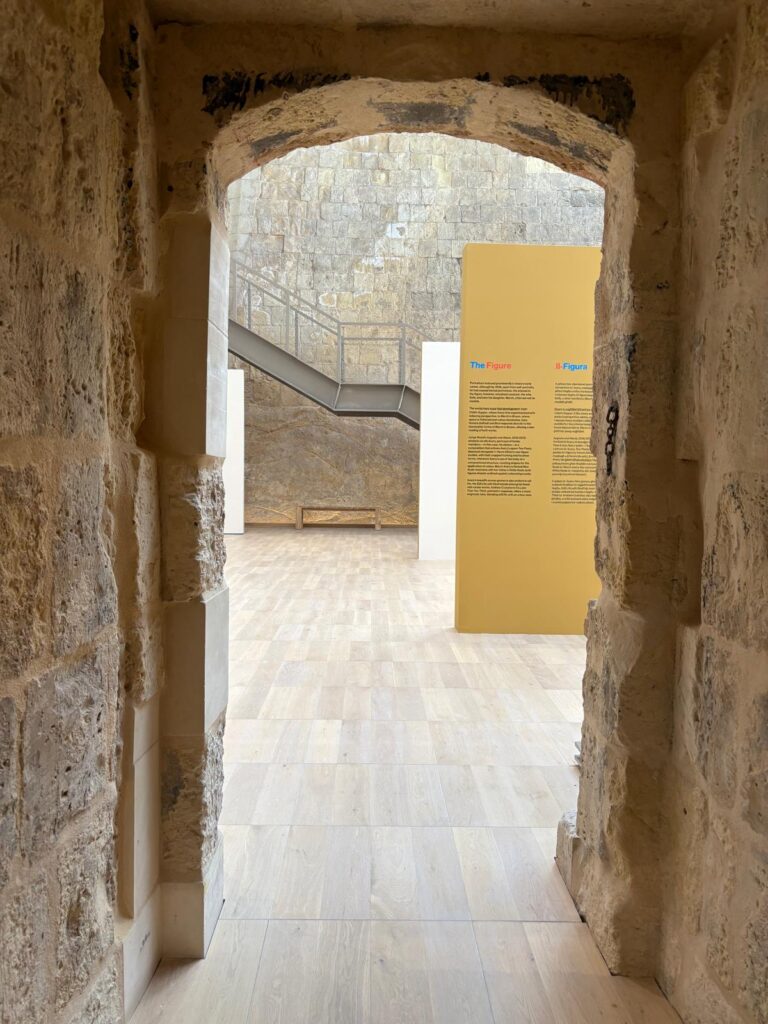

The building itself plays a role in how this dialogue unfolds. Many of MICAS’s galleries curve, and sightlines aren’t always clear. There’s no single point where everything lines up neatly. During my visit, I moved through the exhibition in a slightly chaotic way, starting at the beginning (I think), then wandering off to the end, then looping back to the middle. Sometimes that meant encountering a later work before an earlier one, or catching part of a painting before seeing it fully. For anyone used to the logic of a white cube, this can be briefly disorienting.

But on reflection, that disorientation works in the exhibition’s favour. Avery’s paintings aren’t ones you can just glance at and take in. They reward slow looking and careful attention. The way the galleries fold around the viewer mirrors that process. The curators have embraced the building’s quirks rather than fighting them, creating a viewing experience that encourages patience, curiosity and second glances: all qualities Avery’s work seems to invite.

MICAS – History, Architecture, Presence

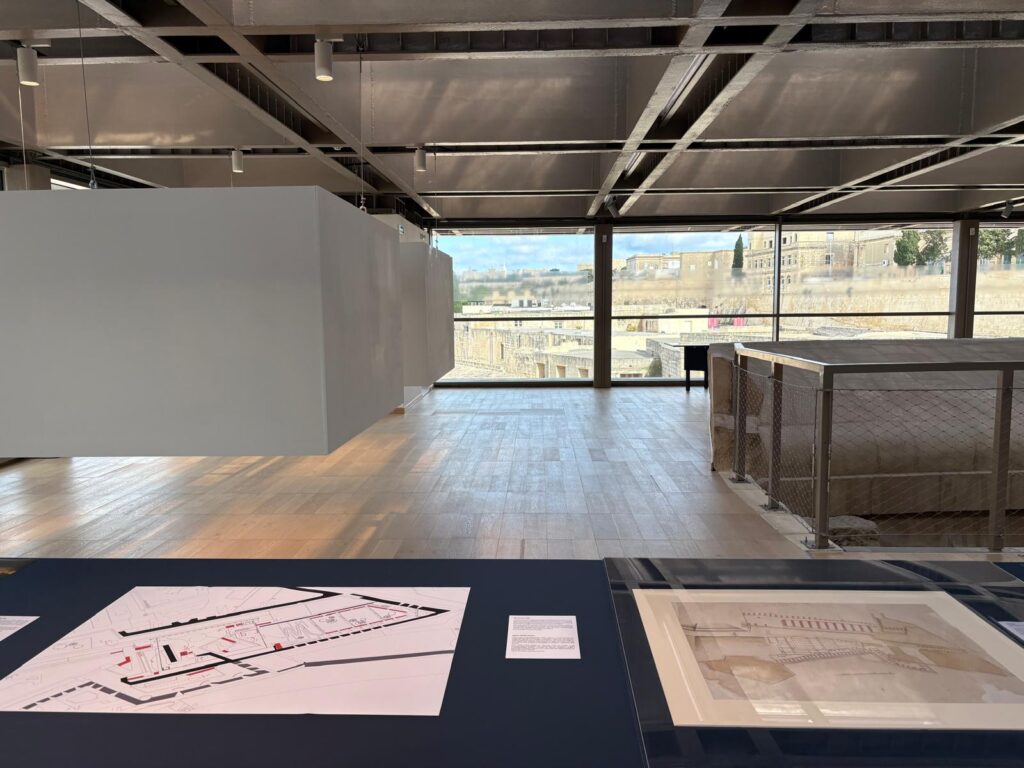

MICAS itself plays a large part in how this visit unfolds. It isn’t a typical museum. As Malta’s first dedicated contemporary art space, it only opened in October 2024 following a long and careful restoration of the historic Ospizio site. This was an 18th–19th century poorhouse, built outside Valletta close to the defensive Floriana Lines.

What’s immediately apparent is how openly the building acknowledges its past. This isn’t a blank white cube that could be dropped into any city. The fortifications remain visible. Older structures are folded into the architecture rather than disguised. As you walk through the space, there’s a real sense of history underfoot, which gives the art a proper grounding.

The historic layering isn’t always seamless, though. As mentioned earlier, the galleries curve and fold in ways that make sightlines partial. I often found myself spotting a work, moving around a wall to see what else was there, then doubling back for a closer look. At first that feels slightly awkward, as though the building is resisting a straightforward route. But once you stop expecting a neat circuit, the irregularity becomes part of the experience.

MICAS asks you to slow down. The architecture demands time and attention in the same way the art does. On this occasion, with an artist like Avery whose work benefits from slow looking, that pairing feels especially apt.

There’s also a broader ambition at play. MICAS clearly wants to be a meeting point for Maltese and international contemporary practice, not just a venue for imported exhibitions. That intention shows in how the space feels active rather than passive. It’s a reminder that buildings shape how we see art, just as much as institutions do – something I was less conscious of at the Royal Academy, perhaps because its architectural language is so familiar to me.

Beyond the Bastions and Space Itself

Running alongside the Avery exhibition is Beyond the Bastions, which charts the transformation of the Ospizio site into MICAS. It makes a strong case for the building itself as part of the museum’s story. Through archival material, models and documentation, the exhibition lays out how the fortifications were adapted into a contemporary art space.

In some ways, I wondered whether I should have started here. While the Avery exhibition focuses on artistic lineage, Beyond the Bastions asks you to think about spatial lineage instead. How places gather meaning over time. How those meanings shift, fade, and are repurposed. From this exhibition, you get a clear sense of the scale of the project, including views down into the depths of the MICAS site, alongside drawings and photographs from different stages of construction.

In a country as layered with history as Malta, this kind of reuse feels particularly powerful. A space that once served a defensive and social function now has a new purpose, without pretending the old one never existed. As you move back into the main galleries history shows up in the thickness of the walls, in the way light enters the space, in the small thresholds between rooms. Old and new sit comfortably together. MICAS feels in use rather than frozen or overly preserved, presumably more so than it has done for some time It’s hard not to marvel at the fact that, centuries after the Floriana Lines were built, part of them would be reimagined like this.

What Is To Become Is Already Here and Final Thoughts

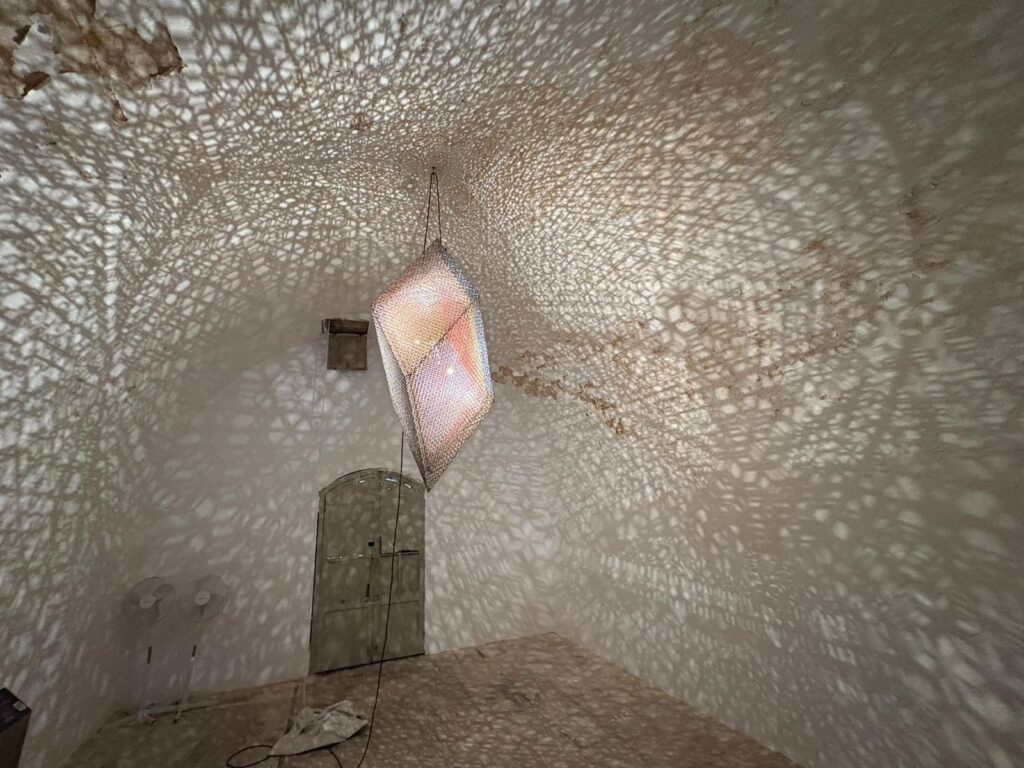

Another exhibition on view when I visited, though now closed (I think*), was What Is To Become Is Already Here, a sculptural show by Conrad Shawcross that made use of light and movement to activate the space. Originally conceived as a kind of prelude to MICAS’s full opening, it felt very much at home in the more intimate barrel-vaulted spaces within the bastion walls, with a few other sculptures dotted around the site. These were works to move around rather than just look at, watching the effect of the shifting light and shadows. Your presence, as a visitor, was crucial.

Placed alongside the Avery exhibition and Beyond the Bastions, this show reinforced the sense that contemporary art is rarely static. Where Avery’s paintings reward stillness and slow looking, Shawcross’s sculptures demanded navigation and physical engagement. As I walked, their forms altered. Light caught edges differently. My eye was constantly being redirected. The contrast was striking, but it worked well. The stillness of the paintings and the movement of the sculptures played on different aspects of my senses.

Taken together, the three exhibitions formed a loose but satisfying circuit. Beyond the Bastions grounded everything in place and history. Colour, Form and Composition encouraged slow looking and reflection on influence. What Is To Become Is Already Here pushed forward, reminding you that contemporary practice can be about change and responsiveness.

Walking through through the MICAS campus towards my hotel, that sense of continuity stayed with me. Historic walls alongside bold colour and pared-back form. Sculptures reacting to light and movement. Everything connected by the idea that art is part of an ongoing flow between past and present, place and practice, artist and viewer. It’s not a feeling you get in every museum, but it lingered long after I left.

*I sound doubtful because, according to MICAS’s website, it should already have been closed when I visited. Did I visit the ghost of an exhibition? That would somehow seem fitting in this historic space.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.