Emily Kam Kngwarray – Tate Modern, London (LAST CHANCE TO SEE)

I respectfully advise that today’s post includes works by, names of, and references to deceased people.

My first exhibition outing for 2026 may be a last minute dash, but nonetheless marks a great start to the year. Emily Kam Kngwarray’s retrospective at Tate Modern is a fantastic introduction to the work of this important Australian artist.

Emily Kam Kngwarray at Tate Modern

As you can see, I’m squeezing in just one or two more reviews of London exhibitions that close in early January, between my series of posts from Malta. The holidays have been a busy time here on the Salterton Arts Review! When it came to choosing which exhibitions to see last minute, there were a couple of contenders. I saw Gilbert and George: 21st Century Pictures at the Hayward Gallery. I wouldn’t mind trying to see Wayne Thiebaud: American Still Life at the Courtauld. But not quite as much as I wanted to see Emily Kam Kngwarray at Tate Modern.

I wanted to see this exhibition because I was hoping for something really different. Sure, Gilbert and George and Wayne Thiebaud are different. Photographs vs. paintings. British vs. American cultural context. But from another perspective both choices lead to an exhibition of art by white males working within a Western art historical framework. Emily Kam Kngwarray: now that could be something completely different, something to shake me out of my London museum-going complacency right at the start of the year.

And so it turned out to be. The exhibition has transferred from the National Gallery of Art in Canberra, where it opened in late 2023 (well, this is a version of that exhibition, at least). It’s curated by Kelli Cole, a Warumungu and Luritja woman from Central Australia, and Hetti Perkins, a member of the Arrernte and Kalkadoon Aboriginal communities.* They developed the exhibition in close collaboration with Utopia Art Centre in the Northern Territory, and with Kngwarray’s descendants. It thus avoids some of the pitfalls of trying to categorise art by Aboriginal artists from Australia in terms of Western painting styles, and attempts instead to share something of Kngwarray’s perspective, of Country, and of Dreaming.

*I suspect there are additional curators for the London version, but this information is very difficult to find on the Tate website. If you know who I’m missing, please tell me!

The Life of Emily Kam Kngwarray

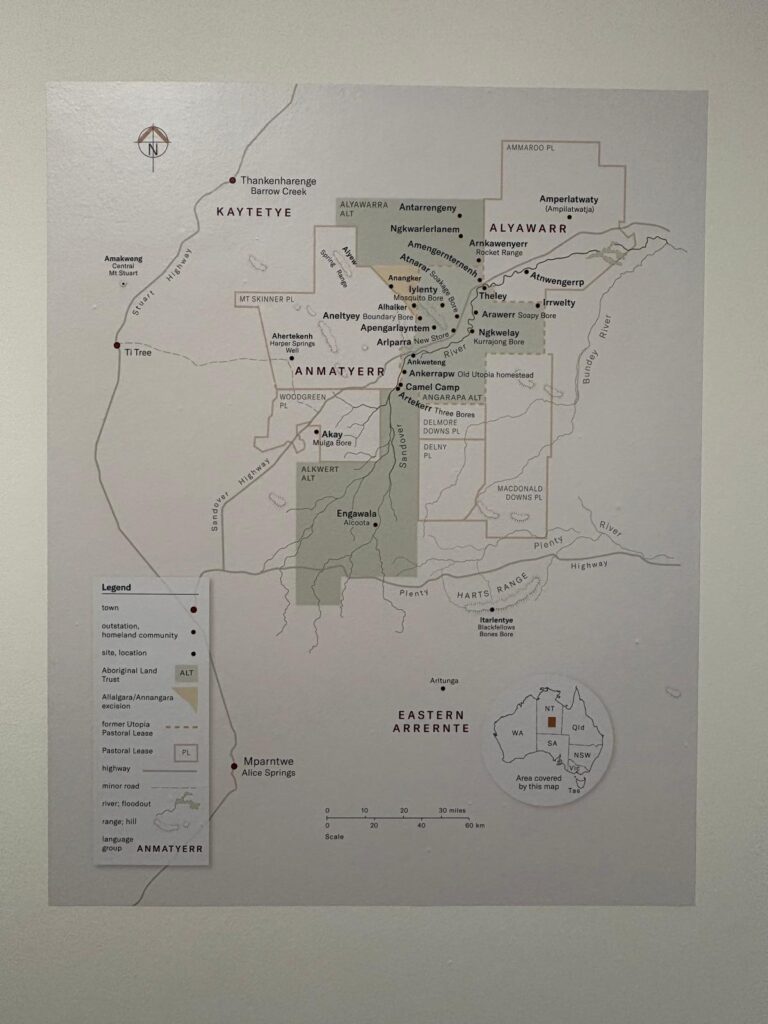

Sources do not agree on the year that Emily Kam Kngwarray was born. I’ve seen 1910, and 1914. But it’s a fact that she was born in Alhalker in the Northern Territory. She was named Kam after the underground seeds and pods of the anwerlar, or pencil yam. Kngwarray is a skin name, part of the kinship system of the Anmatyerr people. Emily came later. Kngwarray remembered the first time she saw European settlers, or whitefellers, as they arrived to drill wells and establish farms. The meeting of cultures was not always peaceful. But many Aboriginal people, including Emily Kam Kngwarray, worked on the farms, often in return for rations.

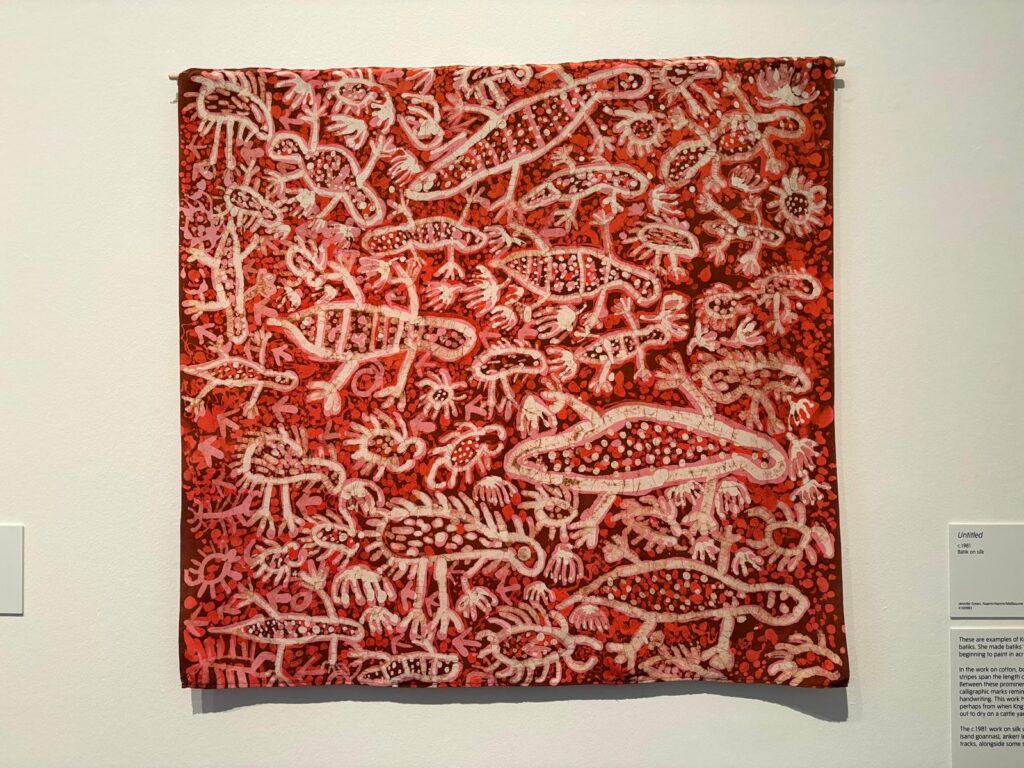

Emily Kam Kngwarray did not have children of her own. A child she was raising, later artist Barbara Weir, was taken from her: part of the Stolen Generations. As part of her people’s traditions, Kngwarray painted all her life for ceremonial purposes. She was already in her 60s when she first turned her hand to what we might call (unsatisfactorily) formal art, as part of an adult education course. The women on the course were taught various types of fabric printing, but it was batik, despite its difficulty, that stuck. Batik, with its layers of wax and dye, is time consuming and resource intensive. It was nonetheless a way for the members of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group to showcase their creativity, and incorporate motifs that had meaning to them into their work. Emily Kam Kngwarray soon became the “boss of Batik”.

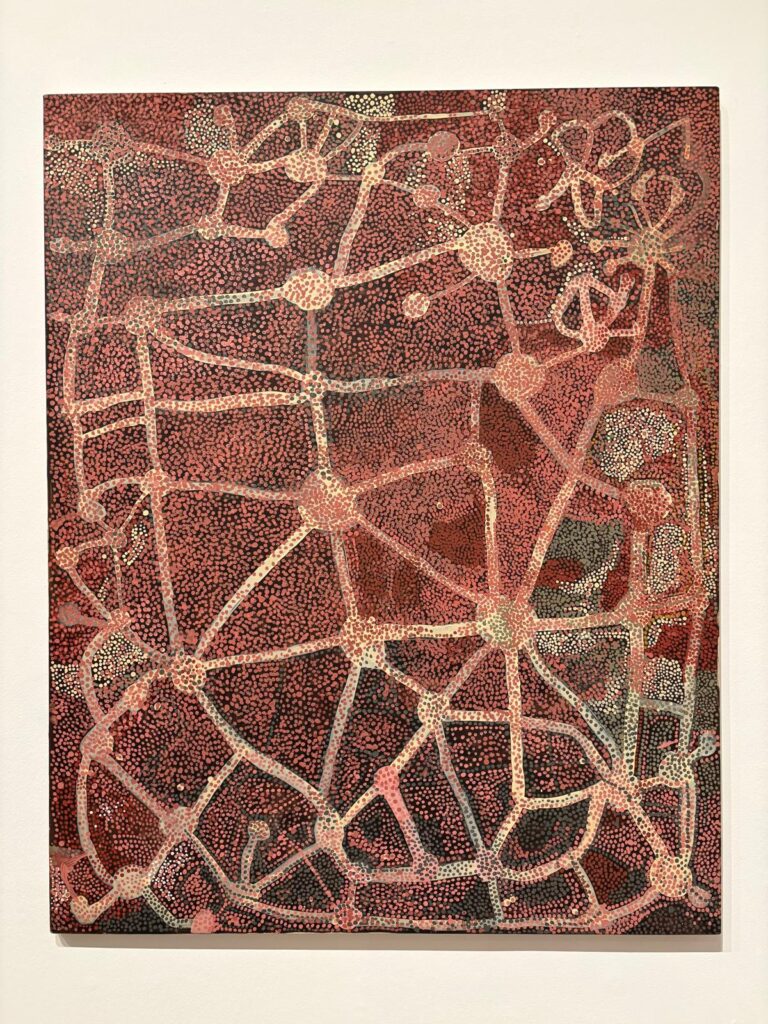

In the late 1980s, CAAMA (the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association) took over management of the Utopia Women’s Batik Group, and ran a summer project where they introduced members to canvas and acrylic paint. Over the next few years, until her death in 1996, Emily Kam Kngwarray produced more than 3,000 paintings. She painted them by laying the canvases on the ground and sitting on them, working from the periphery inwards. Her art was acclaimed within her lifetime, with exhibitions, awards, and selection for the 1997 Venice Biennale (where she posthumously represented Australia along with two other female Aboriginal artists).

When Art is More Than Art

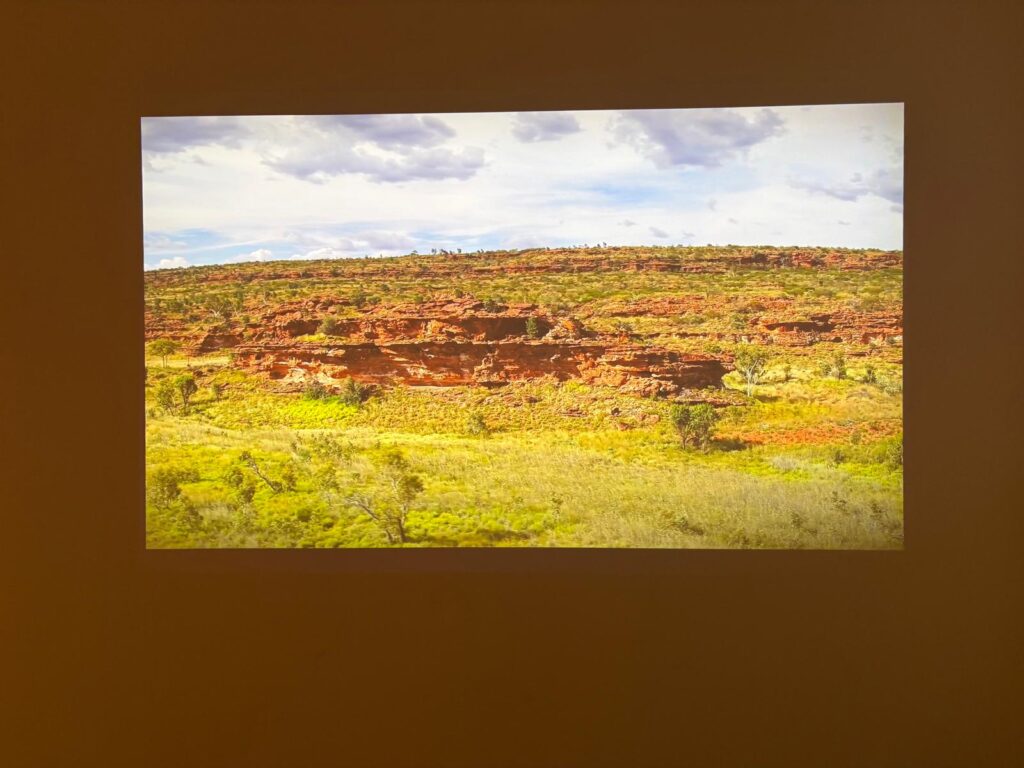

Something this exhibition does very well is to establish a context before letting visitors loose to look at the artwork. Two introductory rooms explains a few things. Naming and spelling conventions, for one. The physical location of Alhalker and Anmatyerr country, along with drone footage. The story of how Emily Kam Kngwarray came to be an artist. This information is set against a small selection of works, and a recording of Kngwarray and two others singing at Three Bores, Utopia. It’s not ‘this is when the artist was born and who their parents were and this is where they went to school’, it’s ‘this is how the artist saw herself in relation to her people, living and dead, and this is what Country meant to her’.

This introduction sets us up well for what follows. Which, in my mind, is two things at once. Firstly, the works look amazing. This is the most beautiful of contemporary art exhibitions. Different scales of canvas and different colourways complement each other, and batik fabrics hang gracefully in the centre of a couple of rooms. It’s brilliant.

But the second thing is that this is an exhibition where we aren’t permitted to slip into lazy habits of only seeing Kngwarray’s work as aesthetically pleasing contemporary art. The curators have an indefatigable focus on what the works mean, even when Kngwarray didn’t make that clear. They point out the emu footprints, the faded feathers of old emus versus the bright feathers of the babies. We see how the lines are not lines, but yams, or the dots sometimes seeds. They show us how some of the paintings are representations of Country, as if from above, or represent journeys, and so capture a duration of time, not a moment. A video made with Kngwarray’s community in 2023 shows the patterns we just saw in one room painted onto skin, in preparation for a dance.

All of this got me thinking. Was I seeing art? Or was this something I can only comprehend as art, but which had a completely different meaning to the person who created it? I lean towards the latter, although I would need to do an awful lot more reading than my quick thumb through the catalogue to construct a sensible argument around it. Yet I have seldom had the feeling I had in this exhibition, of getting a tantalising but still distant glimpse of a completely different world view to my own.

Final Thoughts

I absolutely love an exhibition that leaves me with more questions than answers. I love having my horizons expanded by learning about different ways of thinking, or doing, or being. This exhibition ticked a lot of boxes for me in that sense. I bought a couple of books in the shop, so hopefully I’ll have that chance to sort my thoughts out. But as a first reaction, this is an exhibition that will stick with me. And I don’t think I would have had the same response without the input of First Nations curators and communities.

I’ll never really understand Dreaming, or Country. I can understand the words that translate and describe them, but it’s not something I can ever truly understand. But, for a brief moment, experiencing the work of Emily Kam Kngwarray helped bring me a little closer. I nonetheless feel a little confused about the role of the global art market that brought myself and these works together. There was something of an economic impetus (making work to sell) in the adult education courses that sparked all this. Batik, canvas and acrylic are non-traditional media in Kngwarray’s community. They were introduced to create a new, marketable, plastic form of cultural output. But gatekeeping authenticity in indigenous cultures is also frequently a Western, rather than indigenous, moral panic. I just hope that something of Kngwarray’s high sale prices these days make it back to her beloved Anmattyer communities.

What a great start I’ve made in 2026! If only all exhibitions were this thought-provoking. But then again, if they were, my reading list would quickly become unmanageable. A small price to pay, perhaps, for encountering the world through art in a meaningful sense.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 5/5

Emily Kam Kngwarray on until 11 January 2026

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.