Life Between Islands – Tate Britain, London

A review of Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now, on at Tate Britain. An interesting exhibition, but does it go far enough in exploring what lies beneath the art?

Life Between Islands

There’s an interesting statement at the entrance to Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now, which sets out the Tate’s position on this exhibition. They make it clear that it was in the works before the spotlights on the Windrush scandal and Black Lives Matter protests. And acknowledge the new meanings that these movements lend. Life Between Islands is part of a greater effort on the part of the Tate to diversify their collection and programming; to share stories and histories that are not widely enough understood by the British public.

In order to do this, curators David A. Bailey and Alex Farquharson group the art on display in a semi-chronological, semi-thematic way. Most of the artists whose work is on display are of Caribbean heritage; either they moved to Britain from the Caribbean, or their parents did. All of the works address the Caribbean in some way. The themes include interactions with ancestral heritage, systemic oppression and injustice, and the significance of (the) home.

What results is more contemporary and multi-disciplinary than a lot of exhibitions I have seen here (like this one for instance). Visitors can get acquainted with a range of artists with connections to a range of Caribbean countries. And may fill some gaps in their knowledge of the Caribbean/Caribbean-British experience. That I wish it went slightly further may say more about my own curatorial preferences than the exhibition itself.

Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now

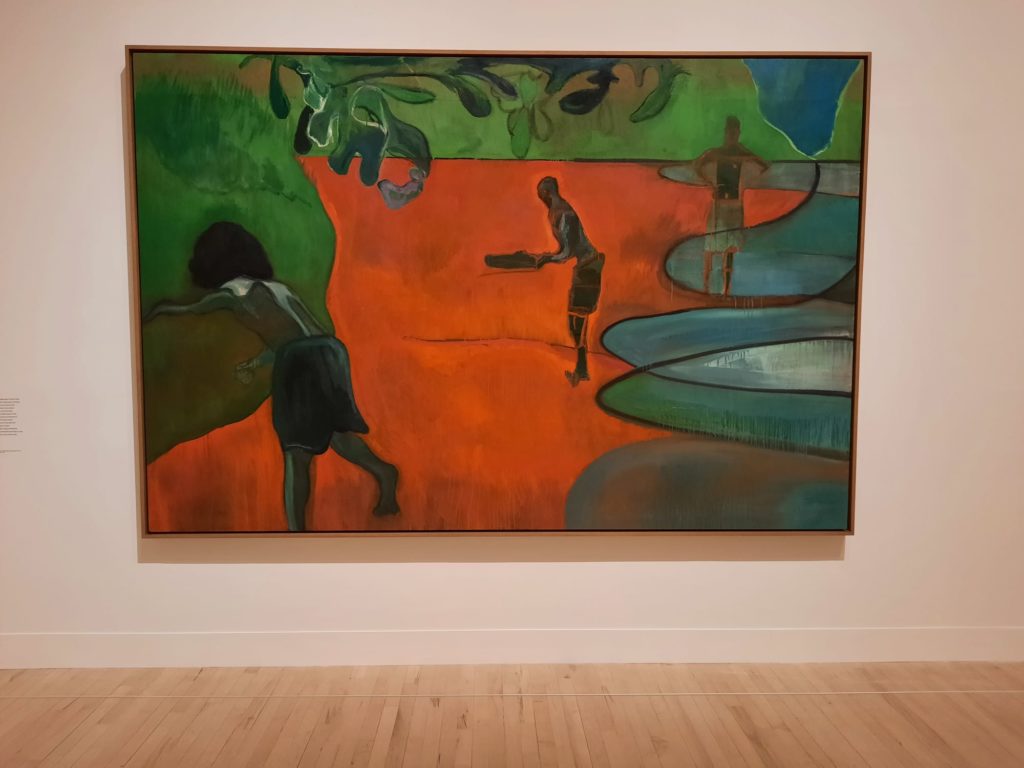

I thought the chronological/thematic approach worked rather well in this exhibition. It opens with a room that acknowledges the debt of Caribbean art to African and indigenous Caribbean cultures. This is set in the context of artists arriving in Britain between the 1940s and 1960s; part of a generation who discovered a new, shared Caribbean/’West Indian’ identity on arrival here. Consciously reclaiming different aspects of their heritage was a means to question dominant cultural values; create solidarity and understanding; draw attention to inequalities. The abstract paintings of Aubrey Williams and sculptures of Ronald Moody are particularly effective here and offset each other perfectly.

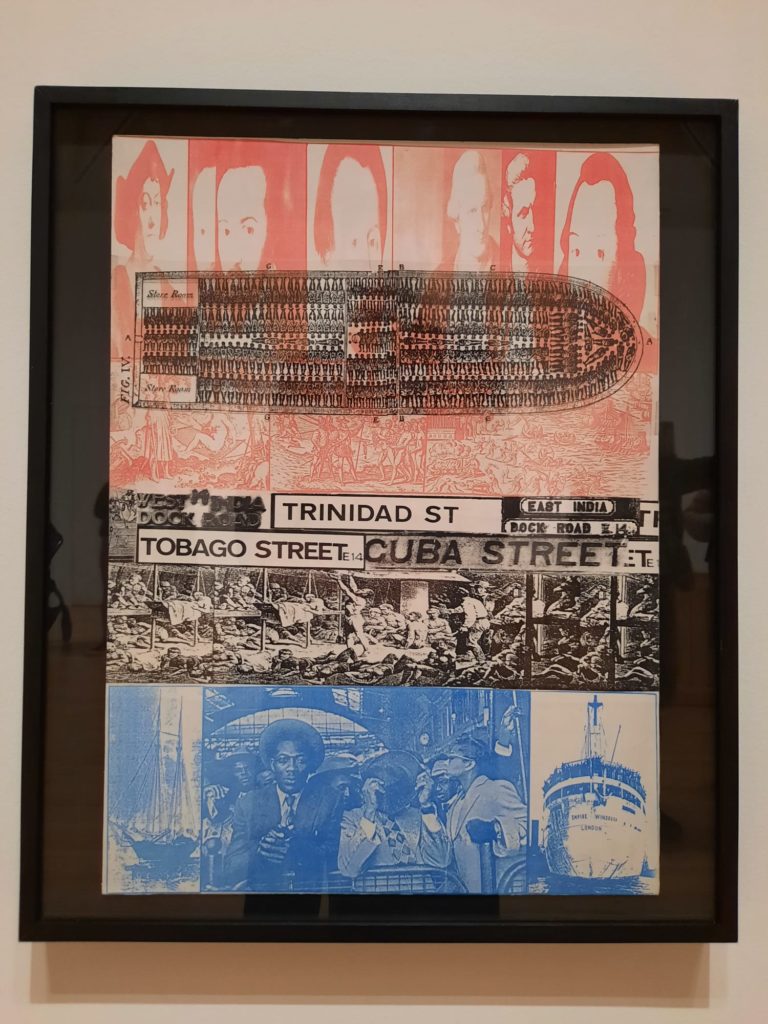

Moving through the exhibition, this marriage of Caribbean-British history and its reflection in art continues. We see political activism from the 1960s onwards, reaching a crescendo in artists who tackled racism head on, for example in the Black Arts Movement. Photographs by Neil Kenlock documenting the British Black Power movement share space with works which surface social injustices more subtly. Michael McMillan’s Joyce’s Front Room, for instance, draws on the migrant experience of African-Caribbean families. The installation imagines the front room of a politically engaged single woman. With unofficial colour bars in place in many shared social spaces, private homes were an important site of social interaction in Caribbean-British communities.

As we continue through the exhibition, we develop a sense of the continued urgency of these questions. The over-policing of Black culture (eg. Carnival) and young people. The ongoing legacy of colonialism and slavery. I particularly liked Hew Locke’s mixed media works combining aristocratic busts with symbols of Caribbean cultures; a reflection of cross-cultural histories. Complex stories are posited as a productive source of knowledge and inspiration; turning towards rather than away from difficult stories in order to understand them and what they mean today. The art in the final sections is often very personal, and all the more interesting for it.

Final Thoughts

If I were to have any criticism of Life Between Islands, it’s that the curators address the knowledge gap that many visitors will have around Caribbean-British history, but then leave those same visitors to draw many conclusions on their own. I know that it was an entirely different type of exhibition, but I came out of the ICA’s War Inna Babylon with a much deeper understanding of some of the structural and systemic forces which have shaped Caribbean-British communities. Life Between Islands touched briefly on some of these (eg. the prejudices which led high numbers of Caribbean children to be streamed into special education schools). But it was only because I had that prior knowledge that I could join some of these dots.

Is that the job of an art exhibition? I don’t know. With the aims that the Tate states at the outset, perhaps this educational thread could have been more overt. At the same time, however, many of the constituent parts are here to kickstart or further an educational journey. It’s a tough one.

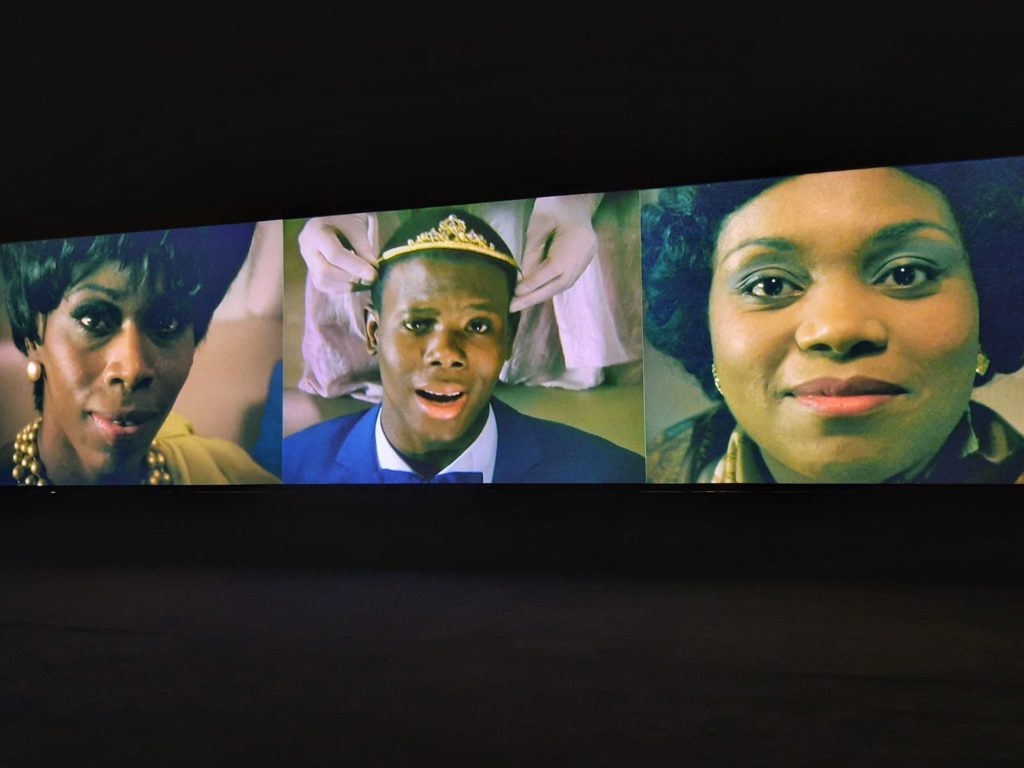

In the meantime, I enjoyed the breadth of work on display – artists I knew, and artists I didn’t. I much preferred Life Between Islands to my other recent outing to Tate Britain, for its clarity and execution of vision. The exhibition is on until April, and is definitely worth a visit. Make sure you have plenty of time if you want to stop and watch the many video works end to end.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now on until 3 April 2022

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.