From Cusco To Ollantaytambo (The Sacred Valley)

As I made my way through Peru’s Sacred Valley, my thoughts were on the different ways in which heritage and tradition is lived and managed in this fascinating region.

The Sacred Valley: A Definition

Firstly, please let me say that this post is mostly the musings of a historian and museologist on Peruvian heritage and tourism. I’ve focused these thoughts on the Sacred Valley. But I don’t want to upset any geographers or pedants by the vagueness with which I employ the term Sacred Valley. The Sacred Valley (or Sacred Valley of the Incas) is a valley along the Urubamba River from Pisac to Ollantaytambo. However, my experience of the Sacred Valley was as part of a G Adventures tour in Peru; they do a ‘full day guided tour of the Sacred Valley’ to get you from Cusco to Ollantaytambo, jumping off point for the Inca Trail and other hikes. So in my mind, everything I did between those two places was the Sacred Valley.

But What Is It Exactly?

Well not to get too theoretical too soon, the ‘Sacred Valley’ is a construct anyway. I can’t find anything to corroborate my guidebook’s claim that the name comes from a driving rally in the 1950s. But the Wikipedia page agrees that the area was previously called the Valley of Yucay. The driving rally theory would make sense as a marketing ploy – it appeals to our sense that, despite being contemporaneous with medieval Europe, the Incas are a mysterious, ancient ‘other’. I live in London where we still speak English like they did in the Middle Ages, eat some foods that have been around for centuries, and continue with a handful of centuries-old traditions. Should we be that surprised if others do the same?

I shouldn’t push this comparison too far of course. Preserving languages and traditions in a colonial context is not the same thing. And life in Peru’s Sacred Valley doesn’t bear a whole lot of resemblance to my day to day in London. My point here is that we should try to understand this place for what it is. The Incas weren’t some ancient, forgotten civilisation. They flourished about 600 years ago and we know quite a lot about them. Besides, originally the people of the Sacred Valley were not part of the Inca Empire. They were Killke: the Incas expanded into their territory in about 1420. When we visit the Sacred Valley today, then, continuity in the face of change (Incas, Spanish, tourists) is a tradition in and of itself. What else can we learn on a day in the Sacred Valley about heritage and adaptation?

Archaeology And Continuity

Firstly, the Sacred Valley is a great place to see remnants of Inca architecture, agriculture and ritual spaces. Here I am employing ‘Sacred Valley’ again in my own larger sense – Cusco to Ollantaytambo. There are some top notch archaeological sites close to Cusco which I described in detail here. Without doing any add-ons, on a G Adventures Sacred Valley day tour you won’t enter into any of the main archaeological sites of the Sacred Valley, but will see a few reasonably close up. Our day started at a lookout over Cusco next to Saqsaywaman. And we ended at Ollantaytambo where those who were so inclined could climb up to a set of Inca storehouses. Somewhere in the middle we got a look at the terraces of Pisac. And there were other sites we glimpsed from our van.

Something that really appeals to my inner archaeologist is the way that today’s inhabitants of the Sacred Valley live alongside so much Inca infrastructure. Agricultural terraces, storehouses, remains of other buildings. There’s so much of it that there’s loads that’s not even deemed worth visiting as a tourist. You just see it by the road or from the train. The Incas distinguished important buildings from unimportant ones by the quality of the workmanship. You will remember me talking about this in the post about the Qorikancha. From what I saw in a single day there is some continuity in everyday building methods (adobe, sometimes on top of stone foundations) but not in the sacred Inca style.

One rather unique aspect of a day in the Sacred Valley is the chance to see Inca town planning. Ollantaytambo is still largely Inca in its layout and housing stock. Again – remember that in years we are only really talking about a medieval village. Plenty of those in Europe. But much more unique in being an example of how people lived in the Inca Empire before the Spanish Conquest. After I climbed up to the storehouses (incredible views), I spent the remaining daylight wandering the streets, admiring the high, angled walls and trapezoidal doorways.

Traditional Skills

A very noticeable aspect of a day in the Sacred Valley with G Adventures is the way that modern tourism can intersect with the preservation of traditional skills. Is there a debate to be had about the performance of tradition – whether employing skills in a way that tourists respond to prevents more modern expressions of a culture? Very likely. (Conversely, my friends at Revolution of Forms are an excellent example of traditional techniques intersecting with a contemporary aesthetic).

Nonetheless, the weaving cooperative we visited at Ccaccaccollo was an interesting case study. Historically a lot of villages in this region have ‘specialised’ in a particular craft, and for Ccaccaccollo this means weaving. However, this village is remote – surprisingly far from the turnoff from anything approaching a main road. Without the partnership they have with G Adventures and Planeterra, the weavers would not have a direct link to all the tourists streaming through the area, and would lose money to middle men. With the partnership, we were brought to them to learn about traditional spinning, dying and weaving, and to purchase goods directly from the makers. Planeterra report that the partnership has restored lost weaving traditions as well as increasing income, literacy and independence among the women in the cooperative.

A similar partnership exists between G Adventures and a pottery-making community just below the Pisac terraces. Some of my fellow travellers felt the ‘performative’ aspect of these stops. And questioned the authenticity of some of the goods for sale. I think this partly comes back to our desire as Westerners for other people to remain ‘traditional’. Why should a few more ‘modern’ products mean that the skill and work that’s gone into them isn’t valid? Selling tradition as an experience seems to be quite a fine balance.

Food Culture

Now interestingly, food culture is an area where there tends to be much more acceptance of combining traditions with a modern flair. If you cast your minds back to my first post about Peru you will recall that it is a culinary capital. A result achieved in part by combining traditional ingredients and traditions with contemporary twists.

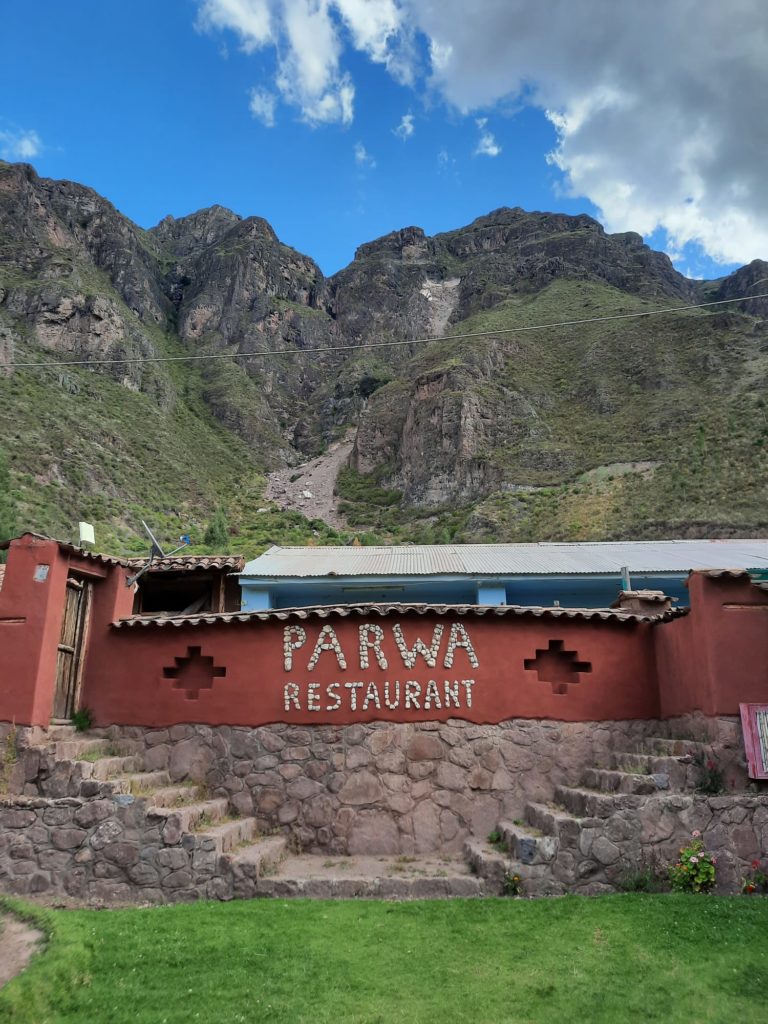

Food is also an industry which lends itself to small businesses and micro businesses. On a single day in the Sacred Valley we ran the whole gamut. A micro business where a lady sold us empanadas on the way to the pottery community. Many small businesses in the town of Lamay specialising in simple roast guinea pigs (I’ve said before I don’t personally recommend this taste-wise). And then Parwa Community Restaurant, another G Adventures/Planeterra-supported endeavour and thus our lunch stop. Parwa Community Restaurant, in Huchuy Qosco, offers a sort of nuevo Andino tasting menu in an absolutely stunning setting. We were able to try modern twists on a lot of traditional dishes, with ingredients supplied by other local micro-businesses. Parwa has benefitted the local community by providing jobs with fair pay and benefits, and investment into clean water and educational projects. And the food is delicious.

So on a day out with G Adventures, you will have the opportunity to encounter the Sacred Valley’s food culture for yourself. If you are making your own way through the Sacred Valley, there are obviously even more opportunities! The favoured spot for the Incas to grow their maize, the Sacred Valley is still very much an agricultural region. Employing local products in both traditional and modern recipes showcases the region’s strengths while satisfying all but the fussiest palates.

Heritage In The Sacred Valley

So the aim of this post was to do some musing about heritage and tourism in the Sacred Valley. I think I’ve achieved that, and hopefully given you a sense of how the Valley’s tourism industry operates. After all, it is an industry. Given the flow of people from Cusco to Machu Picchu, it’s inevitable that communities and individuals compete for a share of the money they will spend. These businesses must respond to the requirements of the market; in this case for experiences that are ‘authentic’ or ‘traditional’. Being able to do this in a way that truly benefits communities, is sustainable, or preserves traditions, is a bonus.

In many ways, I would like to return one day to the Sacred Valley. Perhaps see what there is further off the beaten track. After all, I had one day in this region, and was on a guided tour. We stopped at the same spots as other G Adventures groups, and didn’t often have the opportunity to diverge from the day’s schedule. Or to spend our tourist dollars more widely. The weaving and pottery cooperatives seem to be great examples of community partnership and sustainable business. But how was it that those villages were chosen? What’s happening in the next village over?

A future visit at a slower pace might help me to answer these questions. But in just a day I was able to cover a lot of ground; see interesting Inca architecture; learn about traditional skills; and eat a lot of delicious food (minus the guinea pig). Not everything we do as tourists can be perfect, and the whole issue at hand here is that there isn’t a perfect way to preserve and transmit ‘heritage’, but as a Sacred Valley taster I could have done a lot worse.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

3 thoughts on “From Cusco To Ollantaytambo (The Sacred Valley)”