Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt – British Museum, London

The British Museum’s exhibition Hieroglyphs focuses on the Rosetta Stone in order to tell the story of the decipherment of the language of Ancient Egypt.

A Little Pre-Reading

I wrote once several years ago about an exhibition at the British Museum which left me with a feeling of disappointment: what I thought was quite an academic look at the impact of Greek art on Western notions of beauty turned out in the end to be (in my opinion) a bit of an anti-repatriation tool. Demonstrating the value of objects in ‘universal museums’ where they can be seen and studied by ‘all’. Depending on how you define all, of course.

Hieroglyphs, whose star artefact is the Rosetta Stone normally on display in the British Museum’s Egyptian galleries, is a little too close to this precedent for my comfort. Calls for the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone are relatively rare. Not as vehement as, say, those for the Parthenon Marbles or Benin bronzes. But it’s nonetheless an example of an artefact whose provenance is clearly marked by colonial and Western power struggles. As such, and on the 220th anniversary of its installation in the British Museum, there are some who would like to see it returned to Egypt.

So did the British Museum’s exhibition overcome these concerns and teach me instead about the history and value of the Rosetta stone in the race to unlock hieroglyphs? You will need to read on to find out. A disclaimer first. Many years ago I wrote a thesis relating to restitution and repatriation, so I’m not entirely neutral on this topic. But then again few are if questioned on the subject, whatever their opinions or reasons for holding them.

Hieroglyphs

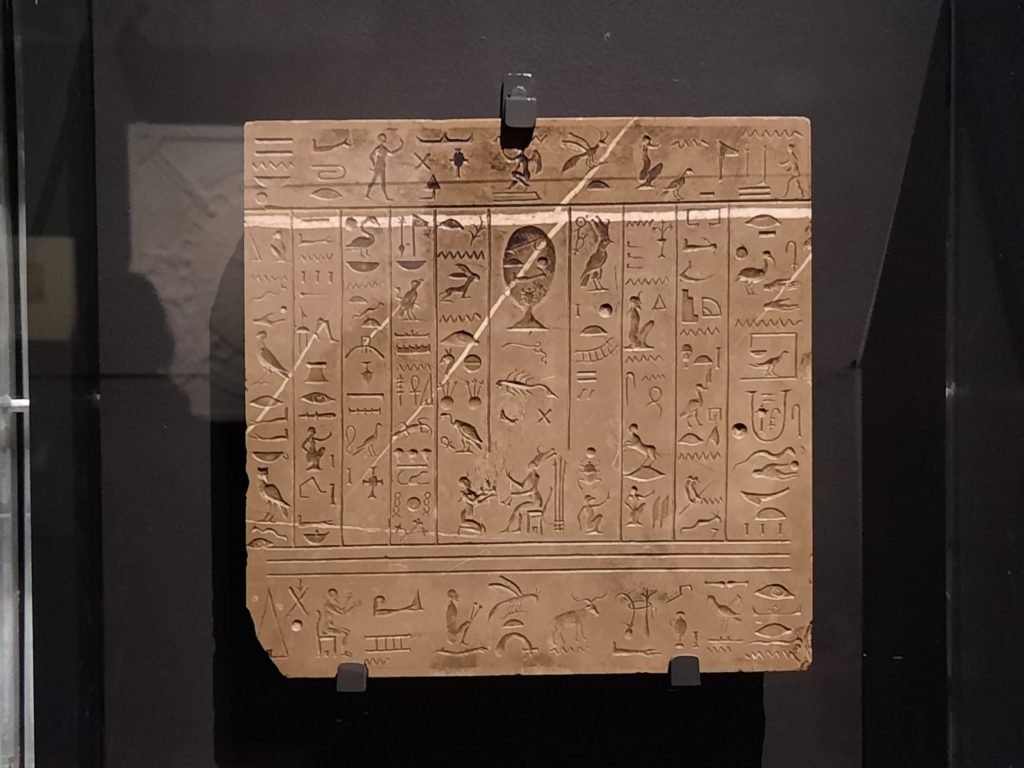

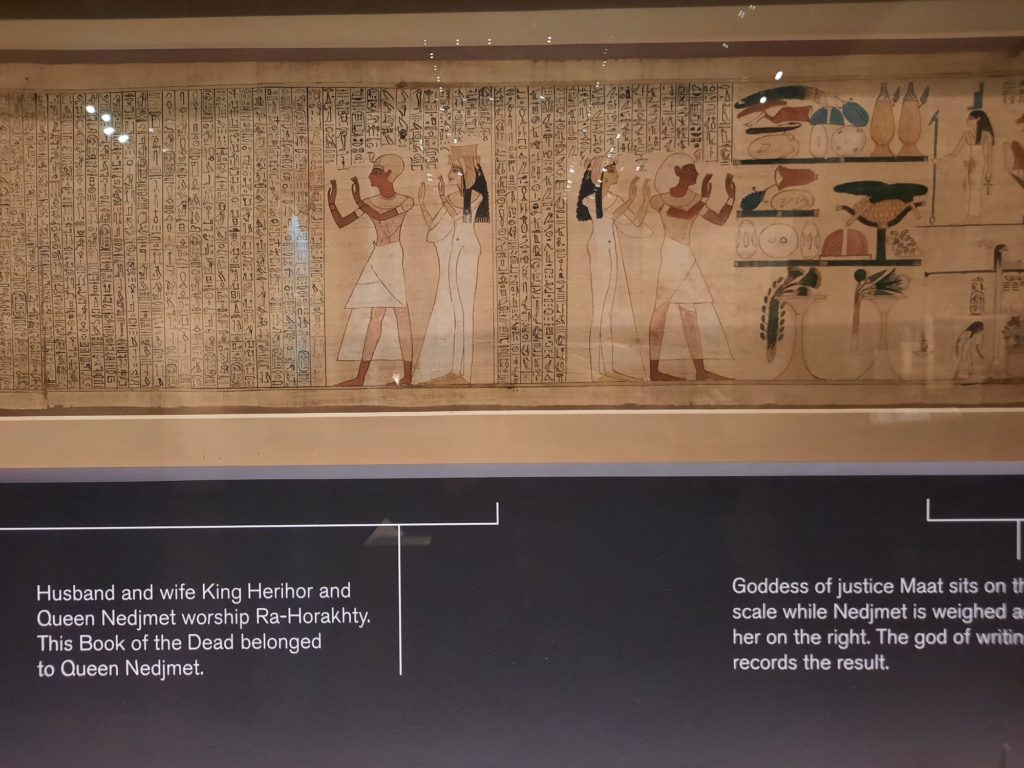

So the story of the Rosetta Stone is not a neutral one. What about the story of hieroglyphs? That depends a little on the story you’re telling. Hieroglyphs are of course a system of writing used in Ancient Egypt. Or one system of writing used in Ancient Egypt, as there were multiple writing systems. Hieroglyphs were the more formal writing style, and you had for instance Demotic for more informal situations. Although both are present on the Rosetta Stone, so the formal/informal distinction isn’t total.

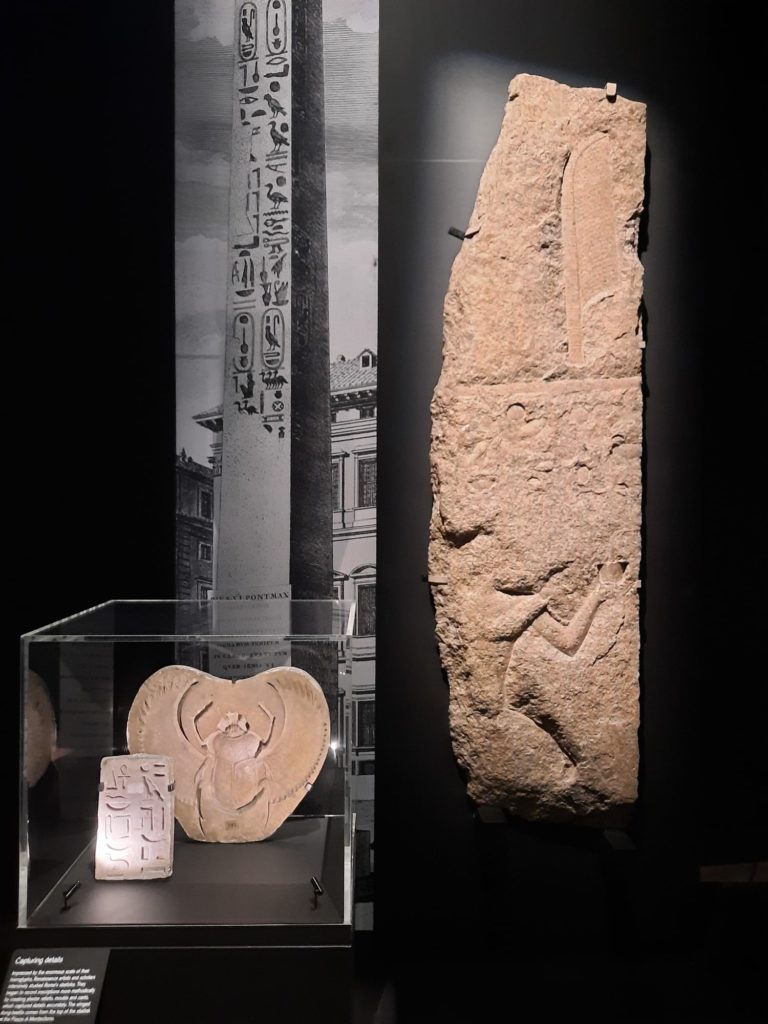

Hieroglyphs are an interesting writing system, in that they are partly phonetic and partly symbolic. There were about 900 distinct signs. Hieroglyphic writing flourished from the 32nd Century BC until the 4th Century AD. It fell into disuse when temples closed during the Roman period in Egypt. Indeed knowledge of hieroglyphs was lost to such an extent that by the Middle Ages they were commonly thought to be some sort of magical language of alchemists. This is partly the fault of etymology: hieroglyph comes from the Greek for ‘sacred writing’. Hieroglyphs were sacred (hence the formal usage), just not in the sense of having inherent sacred power.

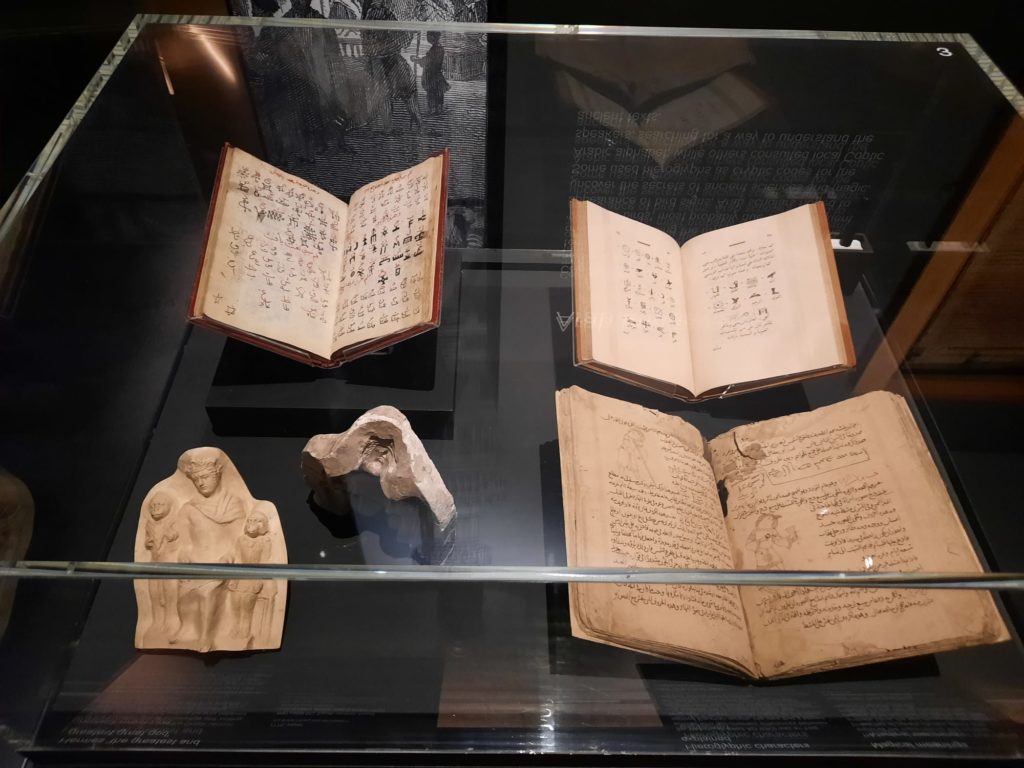

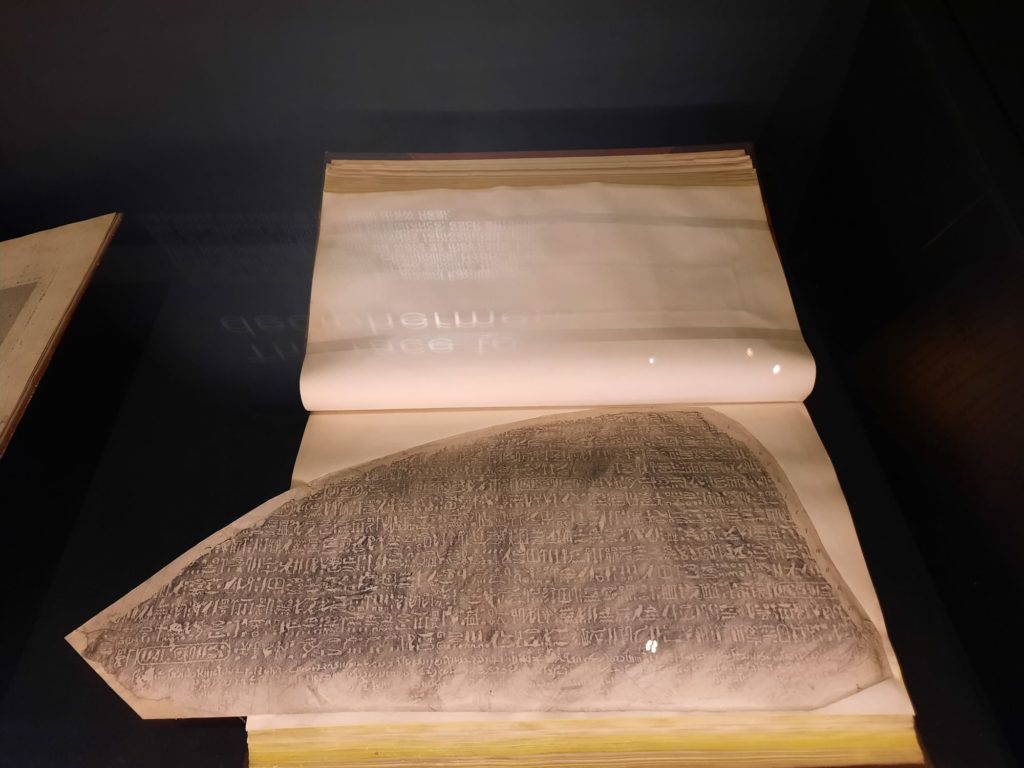

Early attempts at decipherment (eg. Dhul-Nun al-Misri and Ibn Wahshiyya in the 9th and 10th Centuries) failed mostly because of a lack of bilingual documents. Sometimes scholars would correctly guess the meaning of a sign, but that was more luck based on some being more like pictograms than others. The breakthrough in the form of a multilingual document was of course the Rosetta Stone. French troops discovered the stone reused in the walls of a fort they were occupying in 1799. Taken as a spoil of war during the Napoleonic Wars, it has been at the British Museum since 1802.

The Story Of A Race To Decipherment

What the Hieroglyphs exhibition is really all about is this race to decipherment post-Rosetta Stone discovery. Because the stele fragment, famously, repeated the same text in Greek, Demotic and Hieroglyphs. Finally, something to work with! It wasn’t entirely plain sailing, however. It was another couple of decades before the text was fully translated and the key to hieroglyphs unlocked. The central section of the exhibition poses this as a race between the two frontrunners amongst scholars working towards decipherment: Thomas Young, secretary to the Royal Society of London, and Jean-François Champollion, a gifted teacher from Grenoble.

The exhibition design here is really lovely. This is the natural bottleneck of the exhibition: the previous section is introductory and looks at theories on hieroglyphs pre-Rosetta Stone, and the subsequent one is about the knowledge unlocked by being able to read them. Both are organised into discreet sub-topics which you can navigate according to your whims or where you find space. This middle section, though, is chronological and involves a lot of texts and reading in order. Flying papyri above it add visual interest, and the space evokes a library or study. I didn’t take a photo of the exhibition credits and unfortunately can’t find online who is responsible for this nice bit of design.

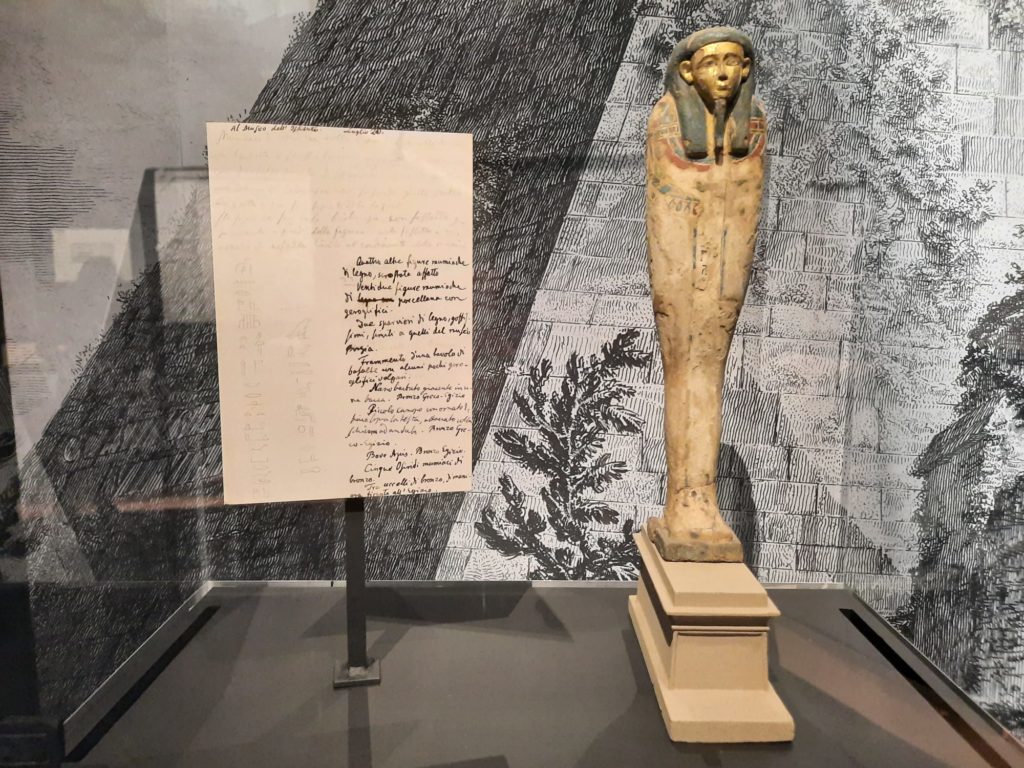

Between the design and the texts, the excitement of the race is almost palpable. Everyone casting aspersions on each other’s work. Important discoveries like the names of royals in cartouches. Champollion fainting when he finally cracked it. It feels like the end of the Enlightenment age of men of letters and the leisure to devote your life such an important yet somewhat impractical topic.

Through A Western Lens

I feel a little conflicted about this angle of hieroglyphs through the race to decipher them. It is a legitimate story to tell: it has had such a huge cultural impact, from knowledge about Ancient Egypt to faddish Egyptomania. And yet, making it about the scholars who unlocked the key puts a very Western spin on it. What did Westerners think about hieroglyphs while knowledge about them was lost? How did Westerners decipher them? What did Westerners do with that knowledge once they regained it? Putting the Rosetta Stone at the centre of it all seems to mean turning away from another story that might exist, either more universal or more local.

The curators have tried to balance the story somewhat and add different perspectives. People from Rashid (ie. Rosetta), including schoolchildren, are present in little vox pop texts responding to artefacts. Near the Rosetta Stone itself is a video on Rashid, an attempt to demonstrate that it’s more than an absence where a stone used to be.

But overall, in 2022/3, it felt like slightly the wrong story to be telling. Maybe I’m being too critical, but a truly universal museum, in my opinion, would have a responsibility to tell universal stories. Not to focus almost entirely on what this ancient culture and its rich history, texts and beliefs mean to us, modern Westerners.

Final Thoughts On Hieroglyphs

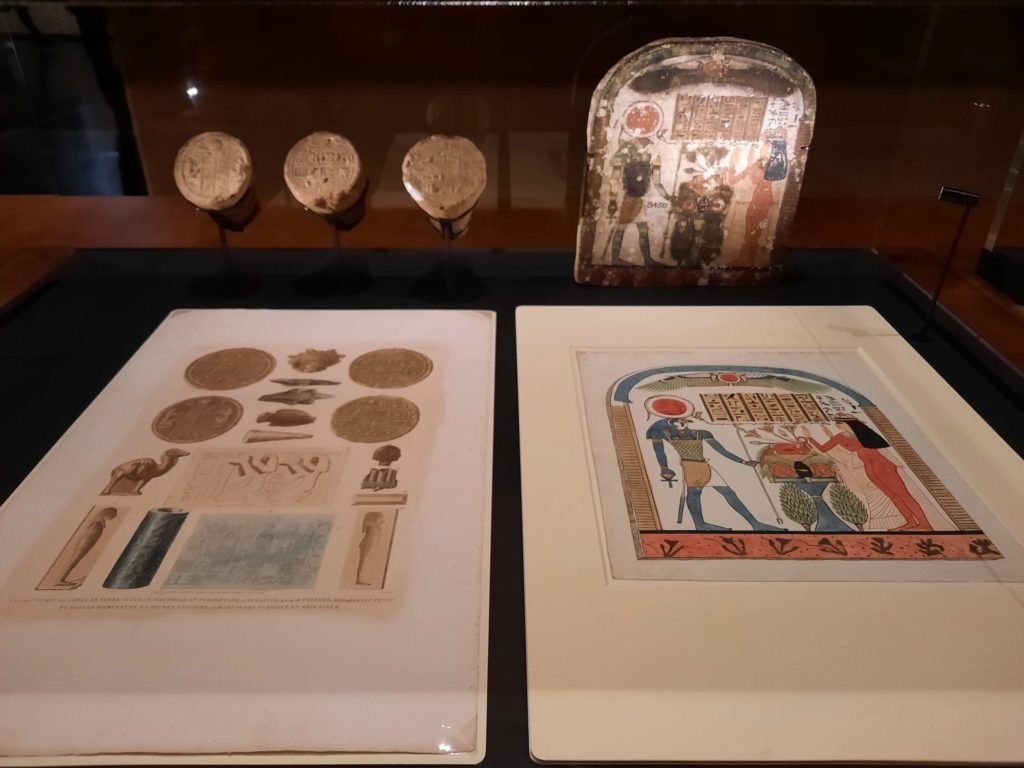

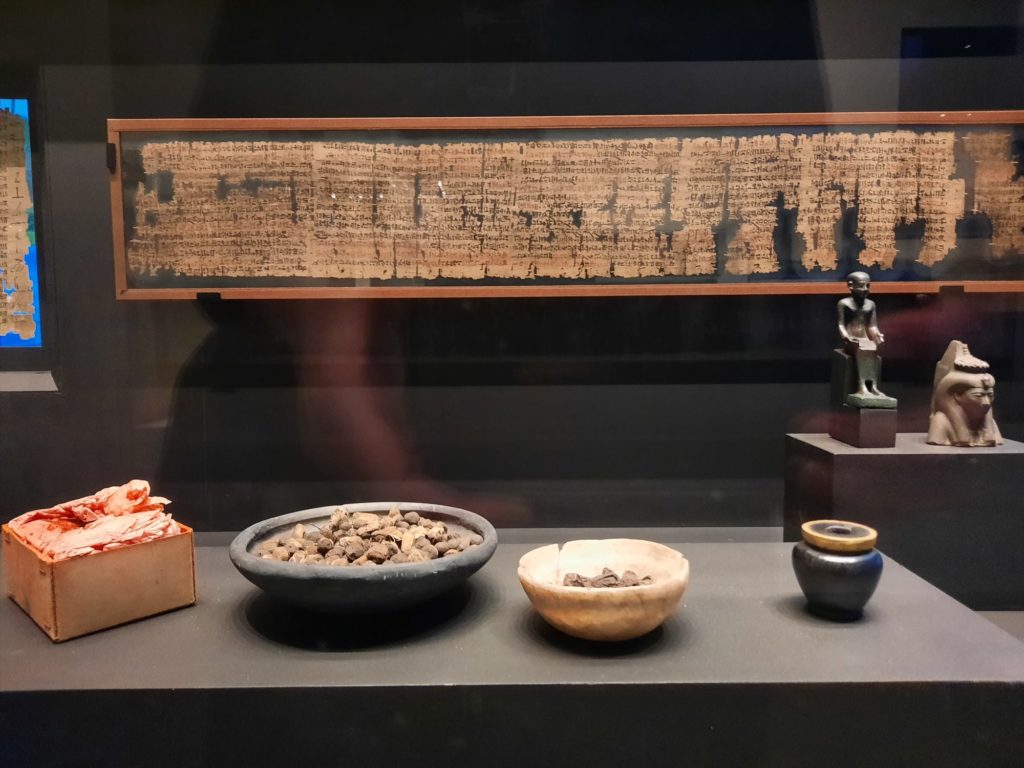

In summary, for me this was a well-produced exhibition, but a missed opportunity to use the resources, collection and reach of the British Museum to tell a different kind of story. There are some fabulous artefacts to see, lots to learn and some interesting stories hidden in there, but I didn’t feel entirely at ease with the end product.

And this is maybe where it comes back to motives. The British Museum, justified or not, is concerned about repatriation: the precedent it might set and the impact on the idea of the encyclopedic museum. I didn’t think about it at the time, but one display about the ‘family tree’ of the Rosetta Stone (the various other versions that exist) could be read as an argument for keeping it right here: ie. this isn’t a site-specific object or a unique one. I’m not saying this is why the exhibition exists, I’m saying that it’s seemingly something either consciously or unconsciously included in the process of planning the exhibition, writing texts and deciding on a narrative. I would love to see something a little more radical, but the universal museum is the wrong place to look for that sort of thing.

If you’re not as preoccupied with thoughts of repatriation and the meaning of museums as I am, you will probably rather enjoy it. It is, as I say, a well-crafted exhibition. For my own part, I need to weigh up selectively what I will get out of similar exhibitions in future vs. the frustrations I might have at the alternative exhibitions I plan out in my own mind. The trials and tribulations of being a reviewer rather than a curator or other museum professional, I suppose.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Hieroglyphs on until 19 February 2023

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.