Isaac Julien: What Freedom Is To Me – Tate Britain, London

Don’t come if you’re in a hurry, but for those with some time up their sleeves, Isaac Julien: What Freedom is to Me is a stylish and thought-provoking, immersive experience.

Isaac Julien

I’m coming around a little to film-based art. When I was younger and less patient, I resented the demand on my time. Because, you see, when it comes to paintings and sculpture, it’s entirely up to you. If you want to spend an hour in front of a painting taking in every detail, go for it. If you want to whizz through a whole gallery in a matter of minutes, that’s your right. You do you. But video or film-based art requires a time commitment which is set by the artist, not you. It’s a little presumptuous (also unavoidable to be fair) but, as I say, I’m coming around to it.

And just as well, because Isaac Julien is a filmmaker. This exhibition, at Tate Britain, consists largely of seven films. Julien’s career began in the 1980s so there is a depth and progression to the offering. But expectations were clearly set as my ticket was scanned: most of the films are upwards of half an hour. Don’t come if you’re in a hurry as you won’t get the full experience.

I was not previously familiar with Julien’s work, but have since learned that he is a London-born filmmaker and artist. In the 1980s he co-founded Sankofa Film and Video Collective, dedicated to “developing an independent black film culture in the areas of production, exhibition and audience”. Many of his films explore the Black experience, specifically the queer Black experience. Other films in the exhibition interrogate migrant experiences, cultural institutions, architecture and history. The length of the films allows audiences to reflect on the subject matter although many of the works are not particularly narrative and require interpretation.

What Freedom Is To Me

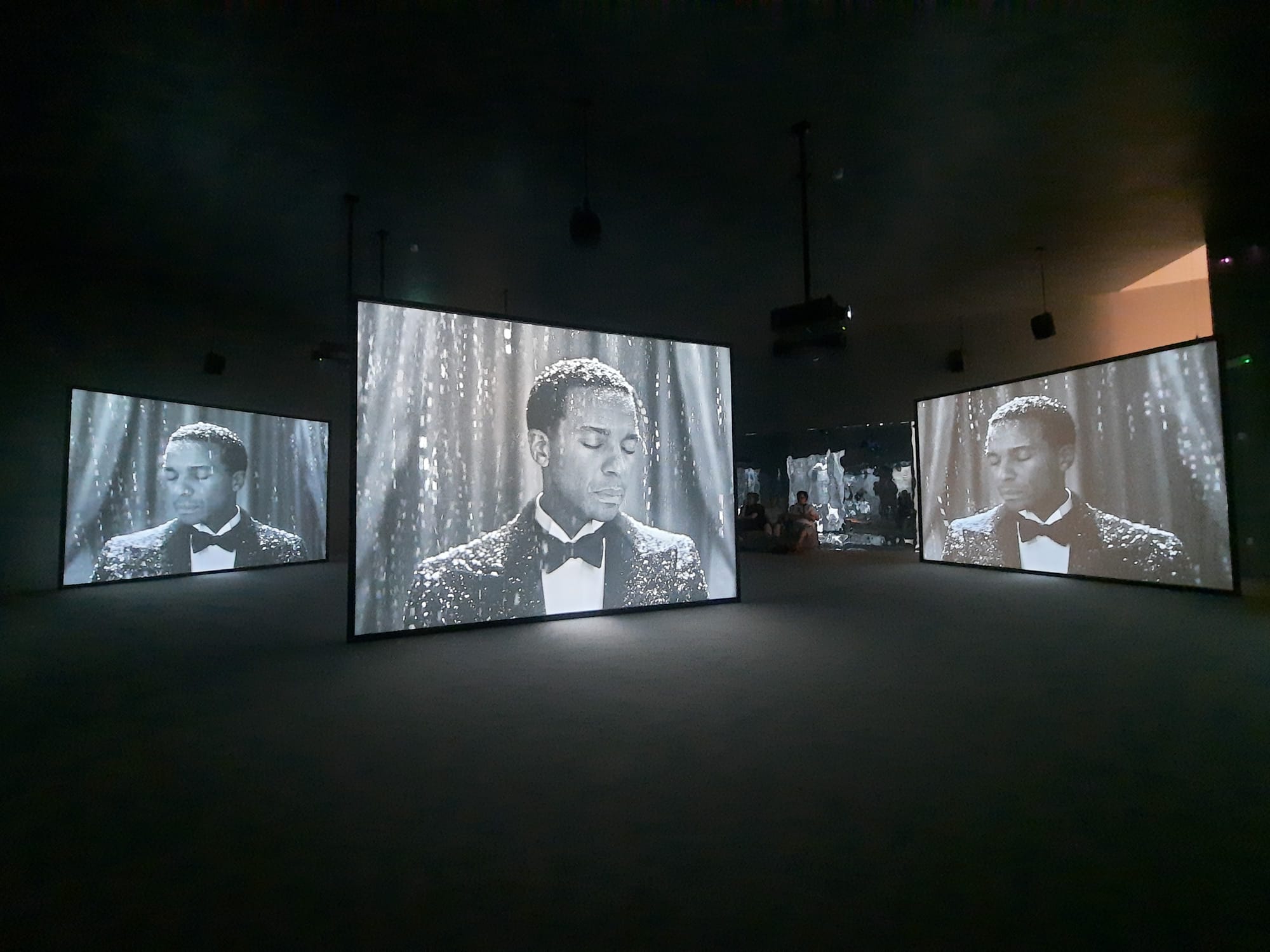

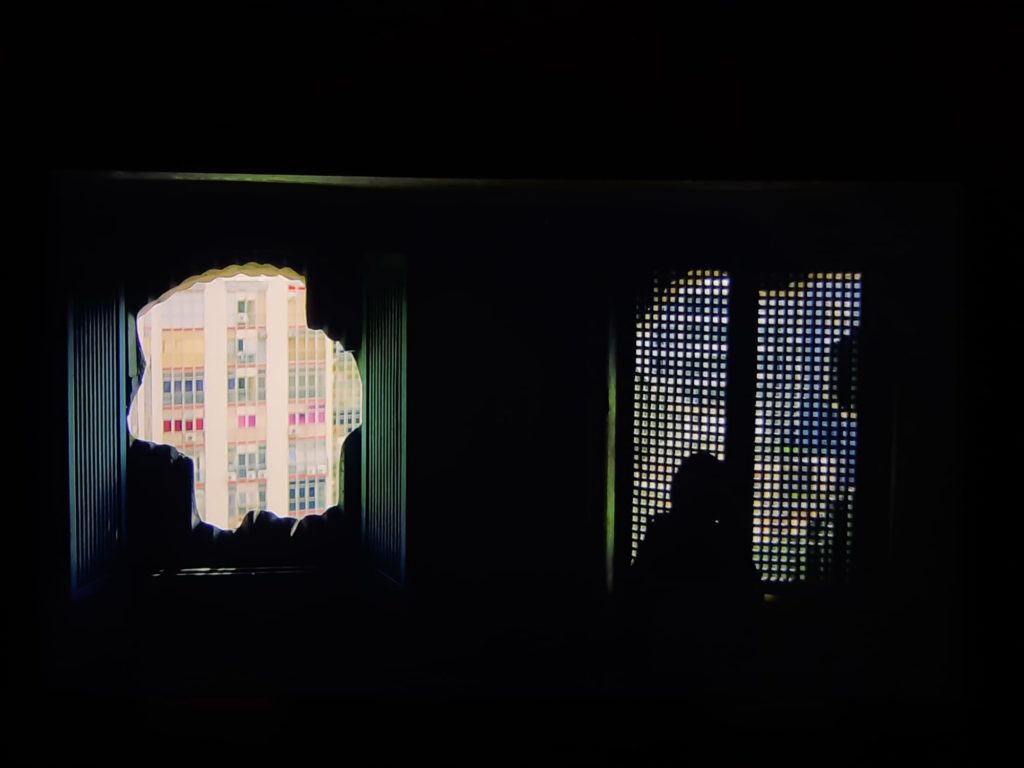

Quite aside from the films themselves, What Freedom is to Me is a superb bit of exhibition design. You enter through a space in which Julien’s 2022 work Once Again… (Statues Never Die) is shown across five screens, with mirrors and sculptures completing the immersive experience. Once you have had your fill in this darkened room, you emerge into a central hub from which corridors spike off towards the other screening rooms. To emerge from the womb-like theatre into this bright, airy, angular place is delightfully jarring. It disconnected me completely from the wider Tate Britain galleries in a remarkable way: I felt like I had arrived somewhere out of space and time, like I was inside Julien’s subconscious and able to access his memories at will. Julien designed the space with architect David Adjaye, and in my opinion it’s wonderful.

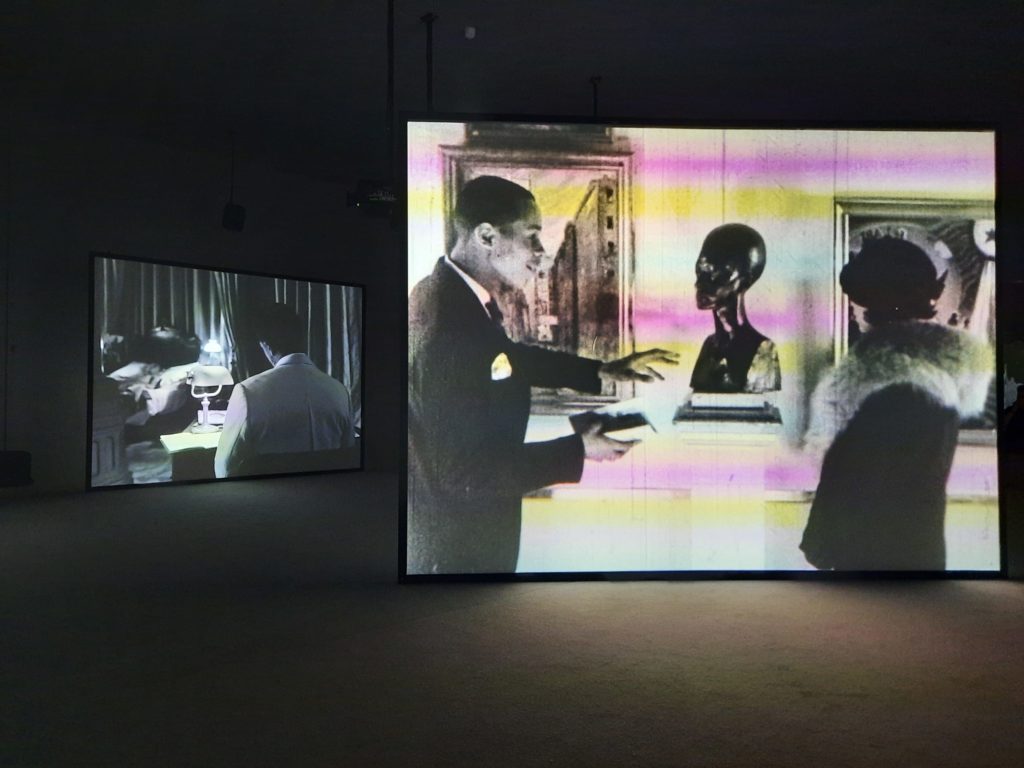

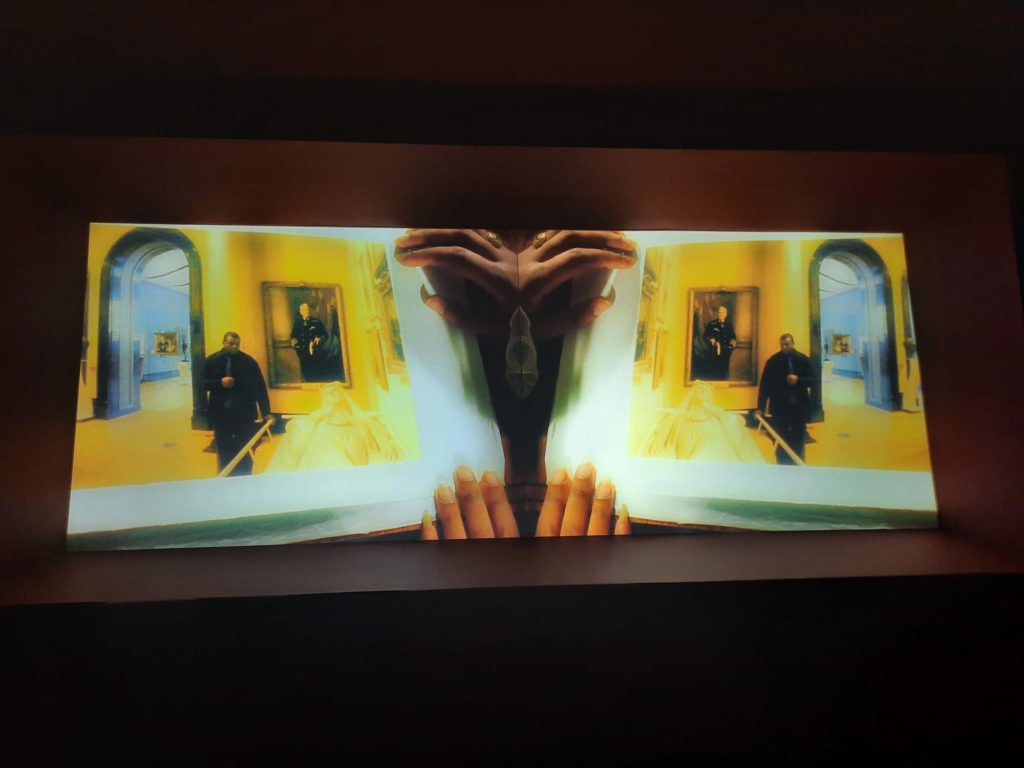

The films are the subject at hand, though, so let’s spend some time on those. The one I’ve already mentioned, Once Again… (Statues Never Die) was perhaps my favourite. It centres on a conversation between philosopher and cultural theorist Alain Locke and Albert C. Barnes of Philadephia’s Barnes Foundation, and references the restitution debates which are dear to my heart. This thread is interwoven with a storyline of queer Black desire between Locke and artist Richmond Barthé, and footage from 1953 and 1970 films which also critiqued Western holdings of African art and objects. It’s all the more powerful for letting the viewer reach their own conclusions.

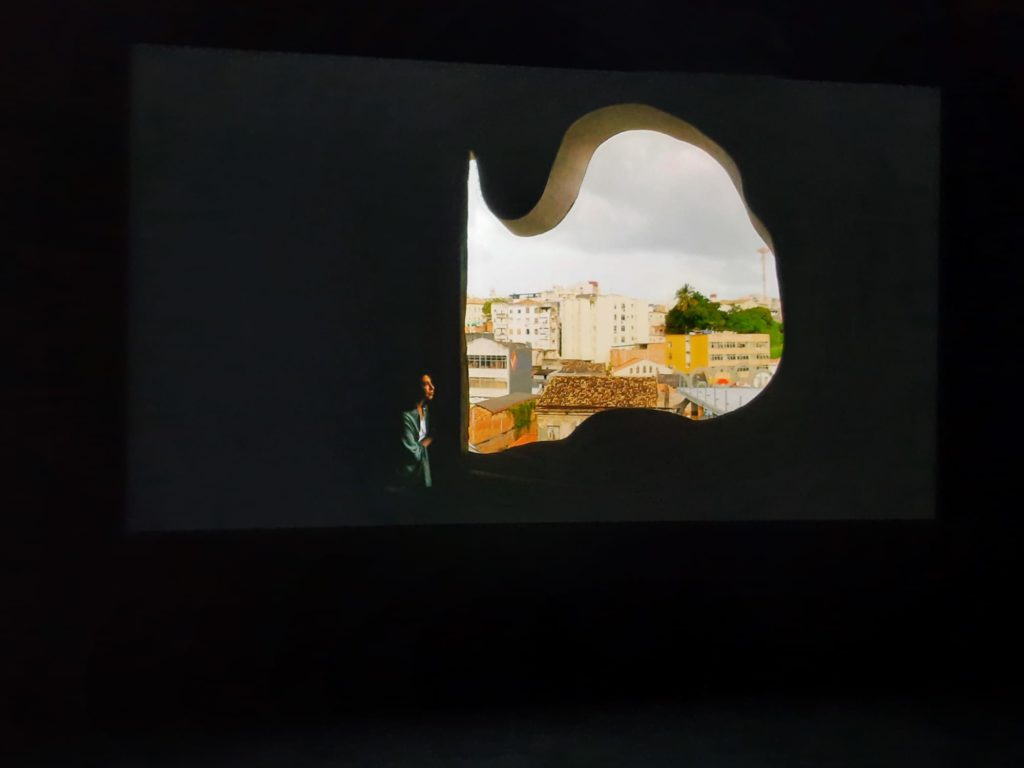

Further on, I particularly enjoyed Lina Bo Bardi – A Marvellous Entanglement, which introduces the Brazilian architect’s work in a pleasingly non-linear way, with two actresses standing in for Bo Bardi at different times in her life. With some of her buildings already derilict 30 years after her death, this seems an important memorial. And finally it’s nice to spot the familiar in Julien’s works – a young Jimmy Somerville in Looking for Langston (1989) for instance, and Sir John Soane’s Museum as the setting for Vagabondia (2000).

Tying The Films Together

Watching these reasonably lengthy art films gives plenty of time for introspection. What is it that brings the films together, or sets them apart?

It’s easier perhaps to start with what sets them apart. Given the length of Julien’s career, there is a clear progression in his work, a development of his unique style and an experimentation with technique. This manifests itself in things as simple as the use of screens. The earlier works on display tend to be shown on a single screen. The experimentation is in the form of camera and storytelling techniques. In the later works we see multiple screens, sometimes mirroring, sometimes showing completely different things, sometimes synchronised. It’s a technique I also saw used to great effect by Kehinde Wiley in The Prelude at the National Gallery. It’s much more immersive and encourages a multiplicity of interpretations: even among the other audience members around you, nobody is watching quite the same film.

What brings them together, then? Certainly a consistent interest in subverting traditional understandings of history, even of time. Julien gets right into the corners of historic periods to expose moments we can connect to, even when our own experience is different. We can empathise with the suffering of Ten Thousand Waves or Western Union: small boats despite their aesthetic abstraction. The inner worlds of figures from the Harlem Renaissance is another recurrent theme, drawn out in dream-like works. That the voiceover in Vagabondia is in Creole seems hardly to disturb us – the character of the conservator is nonetheless our gateway into the hidden histories. Julien’s world is like a repository of stories at risk of being lost or overlooked.

Final Thoughts

There is no doubt that Isaac Julien: What Freedom is to Me requires the sort of time investment we were discussing at the outset. You don’t have to watch the entirety of every film, but you need to see enough to understand them and to think about what they mean (to you). Julien doesn’t make this easy, so it’s not the sort of exhibition you can pop in and out of and ‘get’.

For those who do invest the time, it can be a beautiful, lyrical experience. I loved the feeling of delving into an artist’s subconscious through the red-carpeted corridors. Choosing at will which film to see next. Logistically the Tate make these decisions easy, with summaries of each film before you enter along with a timer showing how long is left before it restarts.

I also saw The Rossettis while at Tate Britain (why not see both exhibitions when you’re there already?) but far preferred this. It’s different, it’s challenging, and it’s an inspiring way to spend a couple of hours.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Isaac Julien: What Freedom is to Me on until 20 August 2023

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.