Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Picture Gallery), Dresden

Dresden’s excellent collection of Old Masters has a fitting home in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, part of the Zwinger palace complex.

Dresden’s Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister

Although my first stop on a recent trip to Dresden was the Dresdener Residenzschloss (Royal Palace), the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister was the one I absolutely did not want to miss. I love a good art collection, and this one is top notch. In my past couple of posts on Dresden I’ve written a little about Augustus the Strong. He is again key to today’s post and to this historic collection.

As a quick recap in case you’re new here and don’t want to go back to those other posts, Augustus II (‘the Strong’) was Elector of Saxony from 1694. And later King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. He had ambitions to match the size of his personality and physical strength, and thus ensured that his capital, Dresden, befitted an important European ruler. He wasn’t starting from scratch but building on the work of his predecessors. Nonetheless the fact remains that under his rule Dresden became a major cultural centre. It attracted artists and scholars from across Europe. His descendants continued to build on this reputation.

You can’t be a major cultural centre without art and artists. And although today the Gemäldegalerie is a collection of Old Masters, it’s important to remember that at the time a lot of the works were contemporary art. The Electors of Saxony (and Kings of Poland etc.) were important art patrons. For instance Augustus III invited Bernardo Bellotto to be court painter from 1747 to 1758. Bellotto was the nephew of Canaletto and also signed his paintings with this name. If you’re a long-time Salterton Arts Review reader, you might remember we saw his Königstein views a while back. The Saxon royal family also made important acquisitions, for instance Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. I guarantee if you don’t recognise the painting’s name, you will recognise the cherubs at the bottom of the canvas.

The Development Of A Collection

So although earlier Electors commissioned and acquired some paintings, it was under Augustus the Strong and his son that systematic collecting began. They expanded the collection significantly over sixty years, for instance by acquiring other collections in part or in full. The best works from the Duke of Modena’s collection were an important addition, for instance, arriving in 1745.

As the collection expanded, it needed more space. There was no longer room in the Residenzschloss, and so the paintings moved to an adjacent building in 1747. The collection moved to its current location in the Zwinger in 1855. It’s called the Semper Wing after architect Gottfried Semper. In the early 20th Century the collection became too large to stay in the Zwinger. The Old Masters remained and the New Masters moved elsewhere.

The disruption of WWII on the Gemäldegalerie collection was significant. Not so much in terms of destruction from bombing, as the paintings had mostly been moved to safety. The building itself was severely damaged in 1945 along with the rest of the city. But it was the post-war confusion and the advance of the Red Army that did it. Most of the collection was confiscated and taken to Moscow, before returning in 1955. The Gemäldegalerie reopened in 1960 after reconstruction. Overall the wartime losses amount to about 200 works destroyed, and 450 which remain missing to this day.

A Comprehensive Introduction To Art History

From its earliest days the Gemäldegalerie has thus represented an important collection. Particularly if we include the antiquities. Johann Winckelmann, famed for reviving popular interest in classical sculpture, frequently visited the collection here. Goethe was another early visitor, enthusiastically stating “I entered this shrine, and my amazement exceeded any preconceived idea!”

Art historians and artists continue to consult the collection today, as well as more casual visitors. In addition to the works I’ve mentioned already, there are important works by Van Eyck, Rubens, Giorgione, Titian, Francisco de Zurbarán, Rembrandt and Vermeer among others. As you will maybe spot from this list of names, the collection spans movements and artists throughout Europe. It is thus fairly comprehensive as far as Old Masters collections go. As a visitor, colour coded walls tell you what you’re looking at, whether Flemish, Italian, French etc. This is presumably part of an unfortunately timed grand reopening of the gallery in February 2020 (after seven years).

For me there were three standouts as a visitor to the Gemäldegalerie. Firstly the Bellotto paintings. There are so many of them, of such high quality, that you could spend a while on these alone. Seeing the familiar Venetian style applied to such a German setting is fascinating. And the detail is such that they became a resource in the city’s post-war rebuild. The second highlight was a conservation studio towards one end of the gallery space. I visited on a weekend so didn’t see anyone at work. But I always love to see the process of carefully researching and restoring paintings.

And finally there is the building itself. The Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) view the Zwinger as a Gesamtkunstwerk. This is a term which also came up in my last post – meaning a total application of art to a setting and its contents. The Gemäldegalerie is part of this. It’s a lovely, grand museum. Although accessibility must be a nightmare, there is something about walking up stairs only to sweep down into a gallery that piques the senses. Old-fashioned leather benches are a luxurious spot to sit and take in some art. It’s an oasis of art and status within a broader royal setting.

Temporary Exhibitions

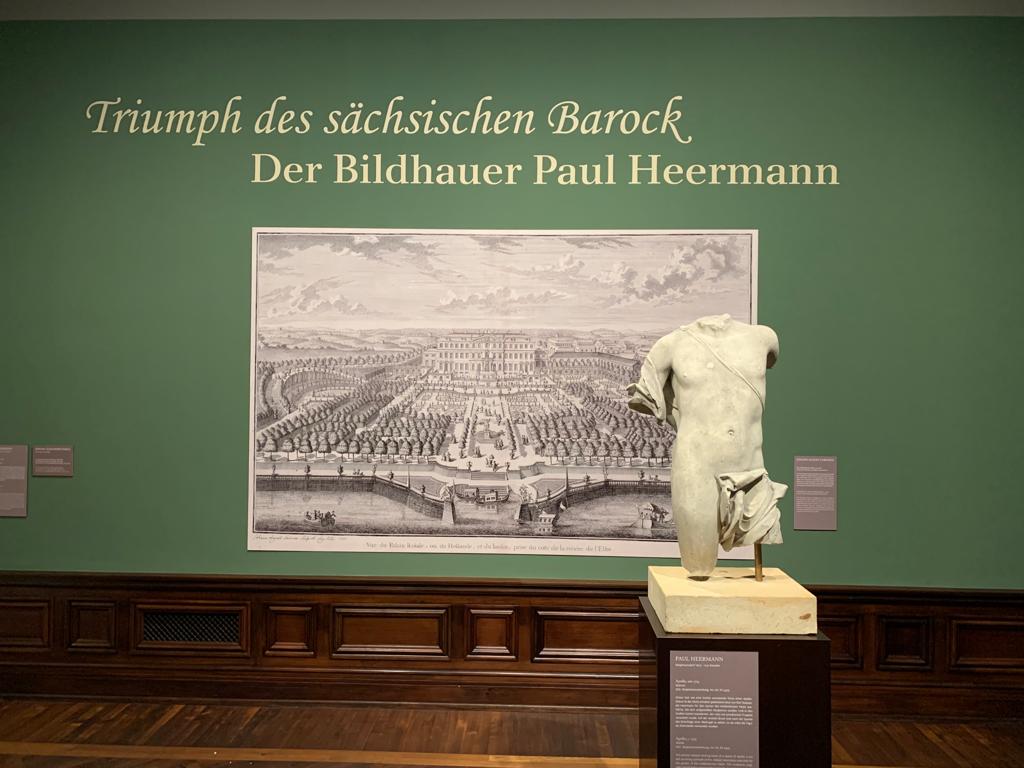

As well as its permanent exhibitions, the Gemäldegalerie displays temporary exhibitions on specialist subjects. The images above are of an exhibition entitled Triumph des sächsischen Barock: der Bildhauer Paul Heermann (The Triumph of the Saxon Baroque: the sculptor Paul Heermann) which was unfortunately on its last weekend when I saw it. Although I can’t recommend it to you, therefore, we can take a quick look as I think it tells us something about the Gemäldegalerie’s approach to programming.

My feeling is that, like the National Gallery, the Gemäldegalerie is not afraid to be academic in its exhibitions. Not entirely: like the National Gallery incorporates contemporary art into its spaces, I can see from their website that the Gemäldegalerie have a range of exhibitions. But some of them are definitely on the niche side.

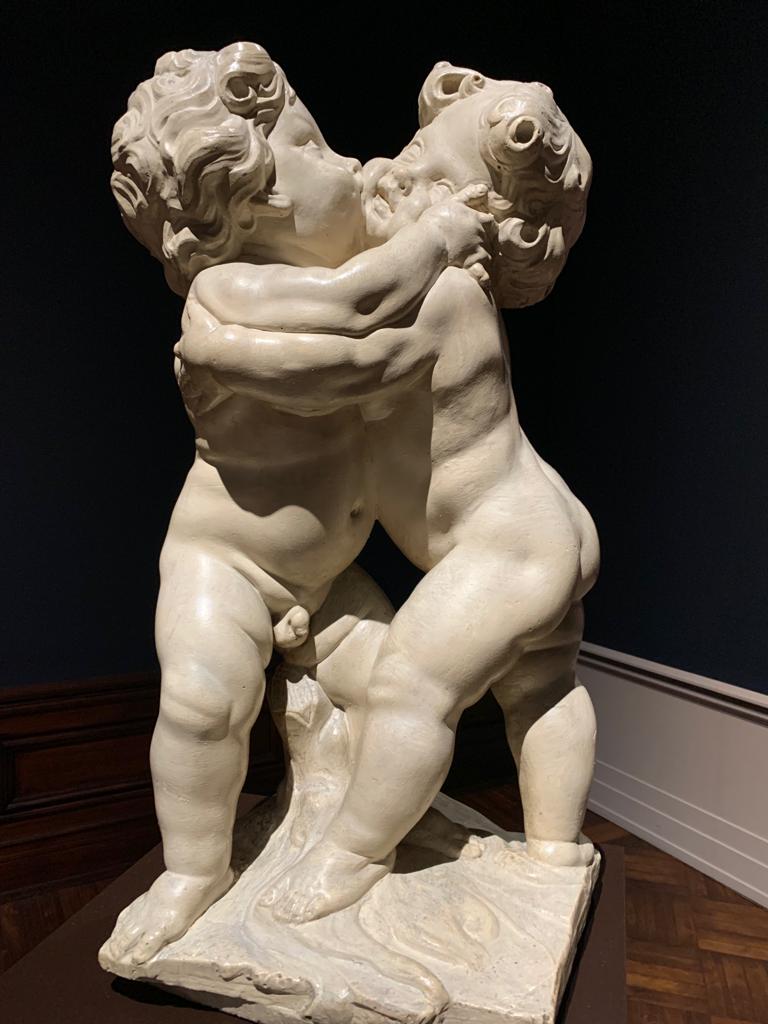

The exhibition on Paul Heermann was due to a recent and important acquisition of a sculpture, Saturn and Ops. It included works from the collection and loans, some of which are fragments of works damaged or destroyed during WWII. Heermann’s work in different media including marble and wood were under consideration, as well as comparisons with rival sculptors. It was relatively interesting and researching such topics is important, but it shows that there is plenty of space in the Gemäldegalerie’s exhibition programme for things that, far from being crowd-pleasing blockbusters, are based on solid and specific art historical research.

I am of course drawing conclusions from the singular exhibition that happened to be on when I visited. With all of my museum experience, hopefully I have picked up other signs correctly and am not misleading you!

The Antiquities Collection

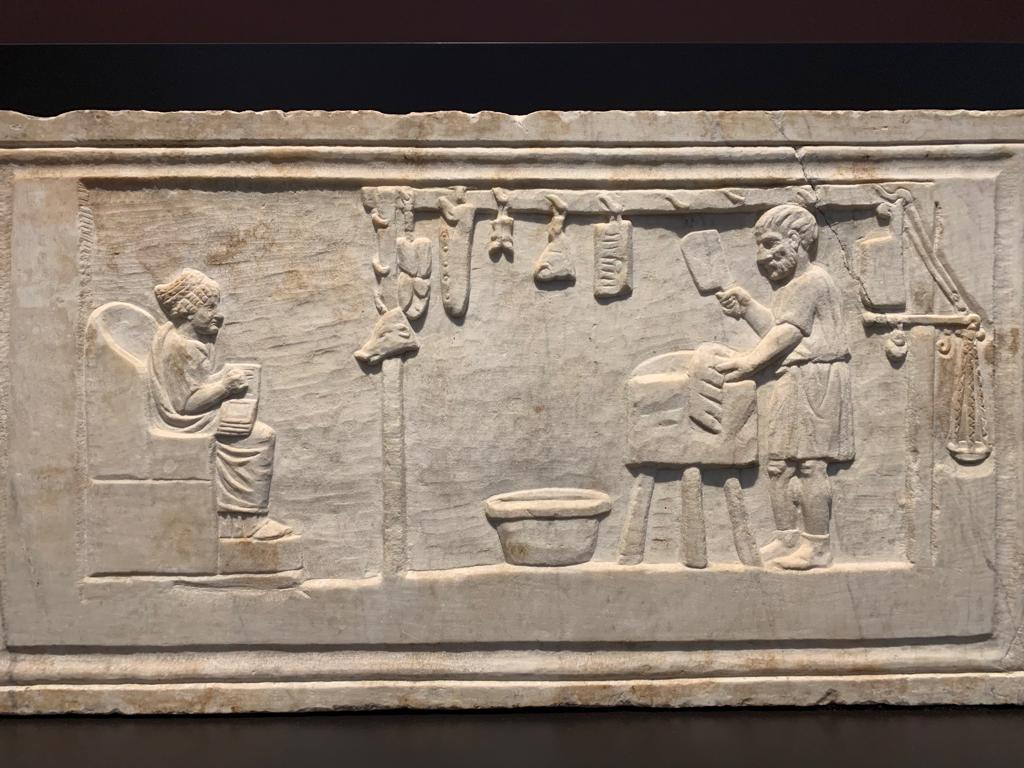

I briefly referenced the Gemäldegalerie’s antiquities collection above, but it is worth diving in a little deeper. In fact, the antiquities are on view in a part of the Zwinger separated by a tunnel, so it’s almost like visiting a different museum.

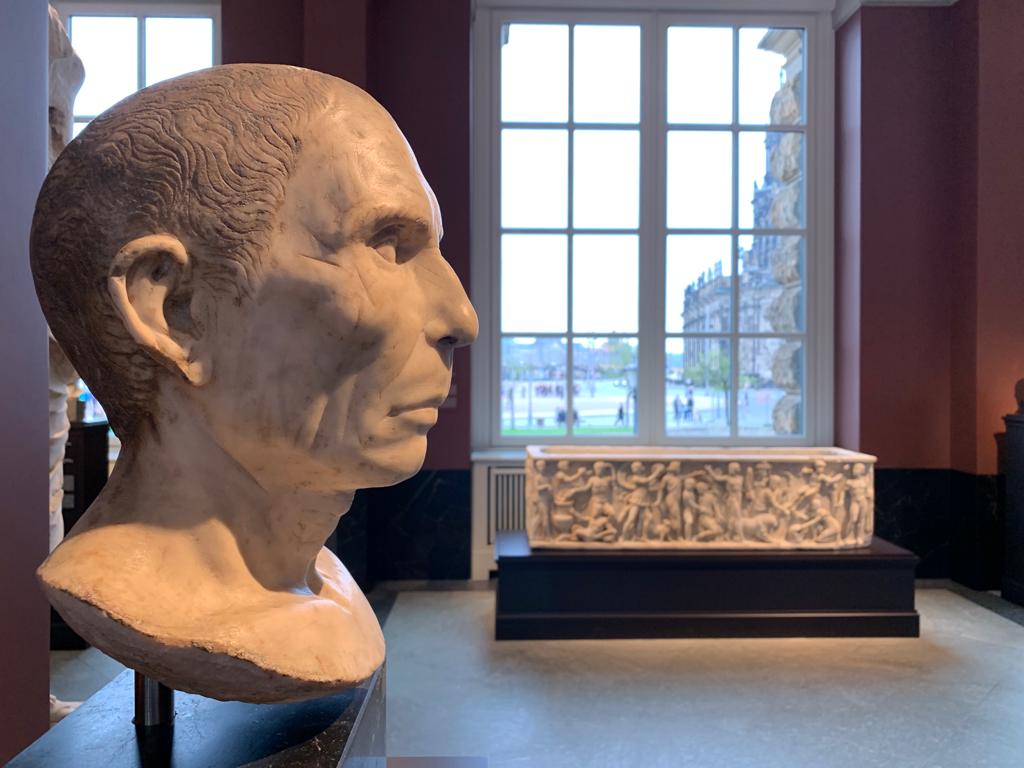

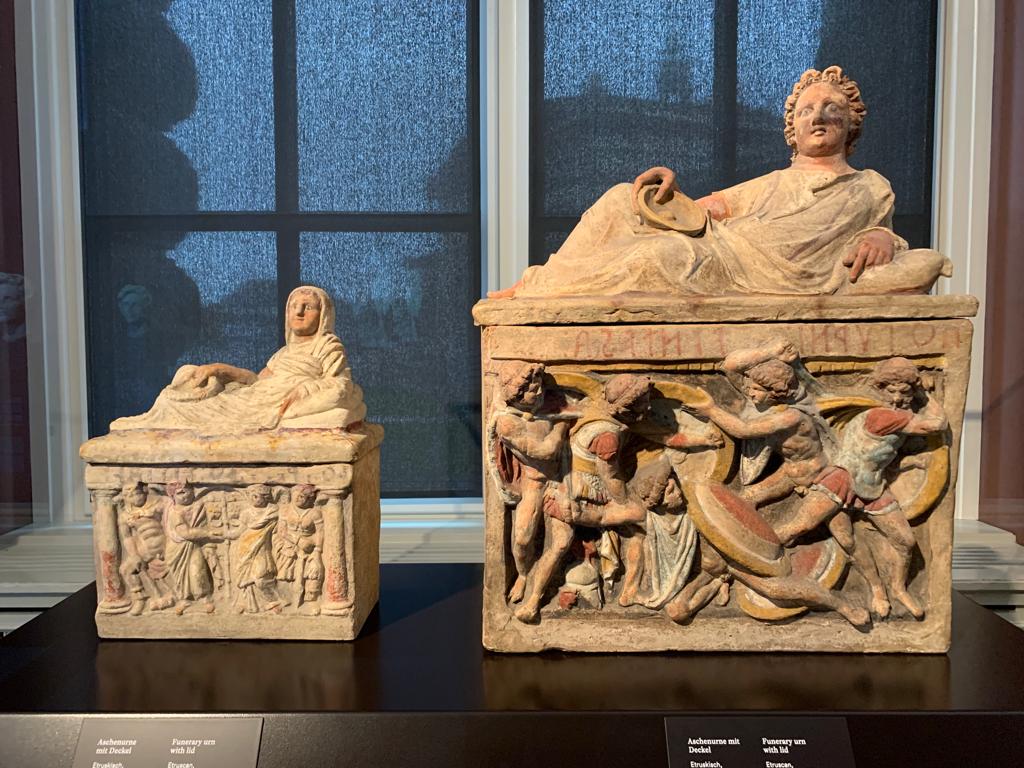

There’s a really great selection of works from a variety of cultures: a lot of Greek and Roman sculptures, but also Egyptian, Etruscan and Cycladic artefacts. Surprisingly or unsurprisingly for a collection connected to Winkelmann (who famously idolised the purity of classical marble sculpture, misunderstanding its original polychrome appearance) there are a few historic interpretations of how different sculptures may originally have looked. It gives added colour to the otherwise serene and pale figures.

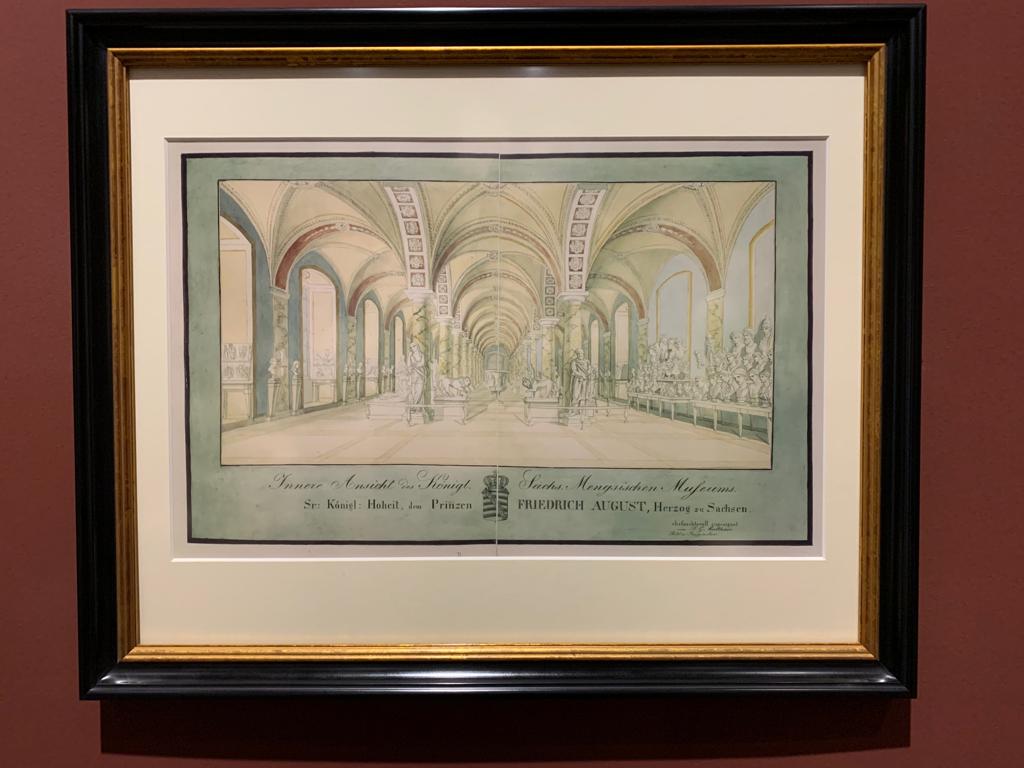

Just past the antiquities is an interesting collection which could easily be its own museum. This is the plaster cast collection of artist Anton Rafael Mengs (1728-1779). As we learned a while ago at the V&A, plaster casts were long an important way for artists to study and draw from important works of art. In the days when travel was infinitely more difficult, good copies were also more positively viewed than they perhaps are today. Mengs built up an excellent collection of casts (sort of an artist’s reference library), and left them to the city of Dresden at his death. The collection adds an interesting historical perspective on the meanings and uses of classical sculpture at different moments in art history. The block of images below shows this collection, the final section I visited in the Gemäldegalerie.

Final Thoughts On The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

Between the Residenzschloss and the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, a visitor to Dresden really starts to get a feel for the Baroque city. It’s an interesting example of an early and (mostly) intact royal art collection, and also of the influence of personality and ambition on seemingly tangential things like an art museum. The Gemäldegalerie is quicker to visit than the Residenzschloss: perhaps a little less state of the art in its exhibition spaces but still rather charming.

A ticket to the Gemäldegalerie also grants access to the other Zwinger museums. There is a Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments, and a porcelain collection. I didn’t have time to see these other institutions, but you would definitely need a half to full day to do them justice. Unfortunately when I visited the Zwinger itself was undergoing significant restorations. The normally enchanting public gardens in the centre were a construction sight. I feel I need to go back another time to get the full effect.

To appreciate the Gemäldegalerie I think you probably need some appreciation of art and Old Masters. If you do, then it’s an impressive collection with some wonderful works. If you don’t, it’s a traditional, not to say slightly staid museum and you might be better off spending your time elsewhere. I’m in the former camp, and had a lovely time looking around and appreciating the art collecting efforts of those long-gone Electors.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.