A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography – Tate Modern, London

A broad undertaking, A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography brings together artists from across the African continent to explore points of commonality and difference.

A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography

Now here is a Tate exhibition I can get on board with. Although I really liked Isaac Julien: What Freedom is to Me at Tate Britain, the two I’ve seen since then (this one and this one) have left me varying degrees of unconvinced. It seems there’s a tendency to overplay concepts and connections at the moment. But not so here. A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is neither any more nor any less than what it claims to be. It is a survey of contemporary photography from Africa (sometimes the African diaspora), crossing countries, cultures, generations and techniques.

That isn’t to say that there isn’t a thesis or thematic connections drawn out by this exhibition’s curators. There most certainly are, good ones in fact, and we are going to take a closer look in the following sections. But the fact that it is a broad survey is certainly a strength. Where I’ve complained recently about certain exhibitions feeling like they have too much filler, diluting a narrow focus, A World in Common draws on a population more than a billion strong. Granted, not all of them are photographers, but you take my point.

Another real strength of this exhibition is that the focus is on the art and not the names. There are a few artists whose work I’ve seen before (including Julianknxx), but other contemporary African photographers who already command their own Tate solo exhibitions (like Zanele Muholi) are absent. This makes it a revelation for all but the most art-savvy visitors. As we go through the thematic groupings, I will call out a few names who I think deserve further attention if you aspire to be one of those art-savvy visitors in future.

Identity And Tradition

The first of three themes in A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography is ‘Identity and Tradition’. As a slight aside, I really like this particular Tate exhibition space. It’s on the second floor of the newer Blavatnik building, and it’s also where we saw this exhibition. It just has a really nice flow to it: a few introductory rooms to get into the swing of things, opening up into a big crescendo of a space where you can put the large-scale, imposing works, and then a final little space for a conclusion. Please excuse me nerding out over architecture and exhibition design for a moment, back to scheduled programming.

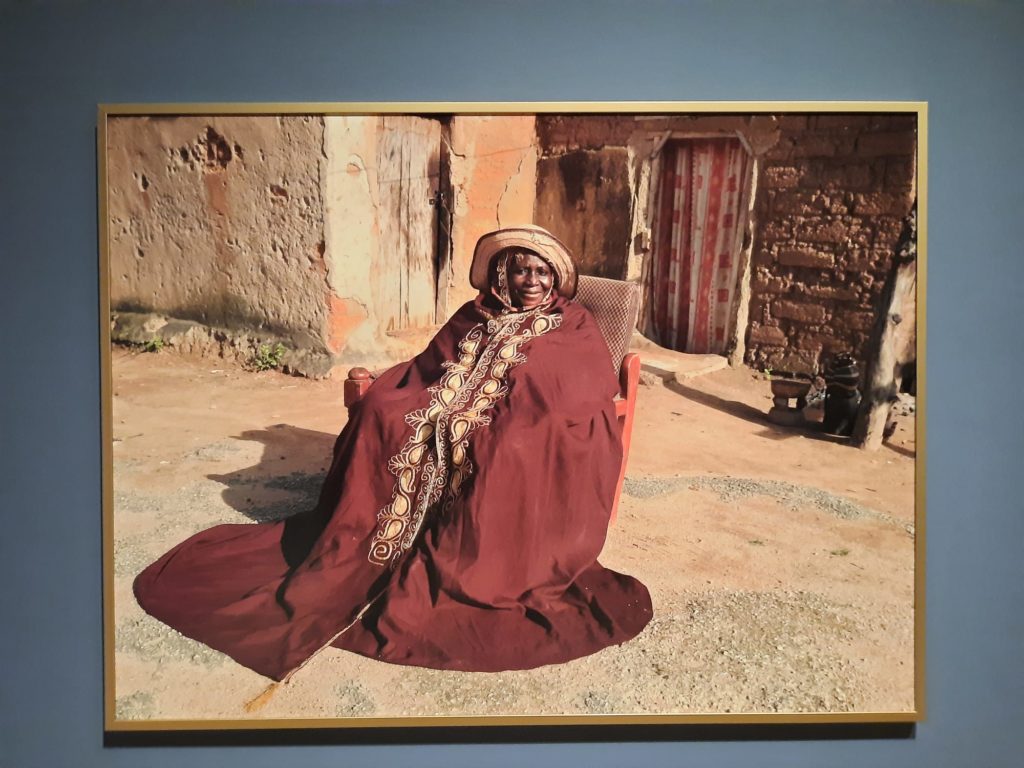

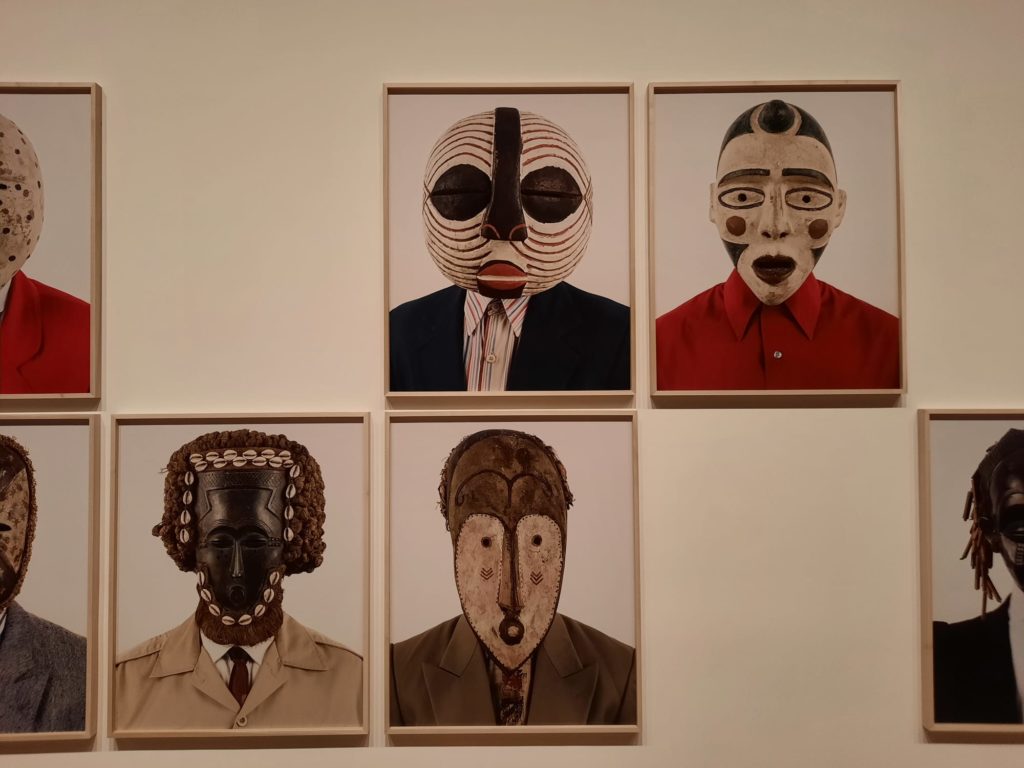

So anyway. Identity and Tradition. Within this theme (and the reason I went on that detour) there are three sub-themes, one per introductory room. These are ‘Queens, Kings and Gods’, ‘Spiritual Worlds’, and ‘Worrying the Mask’. Between these three topics, several key ideas are introduced. The continuity of tradition despite all upheavals of colonialism and its violence. The breadth of beliefs across the continent, from Christianity and Islam through to more syncretic blends bringing together the living and spiritual worlds. We see also the enduring legacy of European influence on the African continent, particularly when it comes to the interrogation of masks and their meaning(s).

Some of my favourite series form part of this theme. An absolute stand-out for me was Tipo Passe, a series by Angolan-born artist Edson Chagas. In it, sitters pose for typical passport photos, only they wear traditional Bantu masks, hiding their features. Their invented names, blending European first names with African surnames, highlight the ongoing role of colonialism in the formation of identity. It’s clever and witty, yet makes us question the display of traditional masks divorced from tradition. I also liked UK-born Khadija Saye‘s dream-like series of self-portraits, and Zimbabwean Kudzanai Chiurai‘s borrowing from the Old Masters, specifically Artemisia Gentileschi.

Counter Histories

The next theme is ‘Counter Histories’: photography’s ability to interrogate, undermine and refashion accepted histories. Particularly relevant in the African context, where agency in the face of the predominant (Western) narrative was lacking for so long and is still an ongoing process. Again there are sub-themes: ‘Family Portraits’ and ‘The Living Archive’. The themes this time feel a little more disparate than in the last section. Family portraits is quite self-evident. It’s a mix of studio photography (eg. James Barnor‘s work in Ghana) and series on found families, like Sabelo Mlangeni‘s series on gay life in rural South Africa, or Hassan Hajjaj‘s portraits of an all-female, Muslim biker gang in Morocco. I particularly liked 1960s studio photographs by Lazhar Mansouri, amongst the oldest works on view and a snapshot of a bygone Algeria.

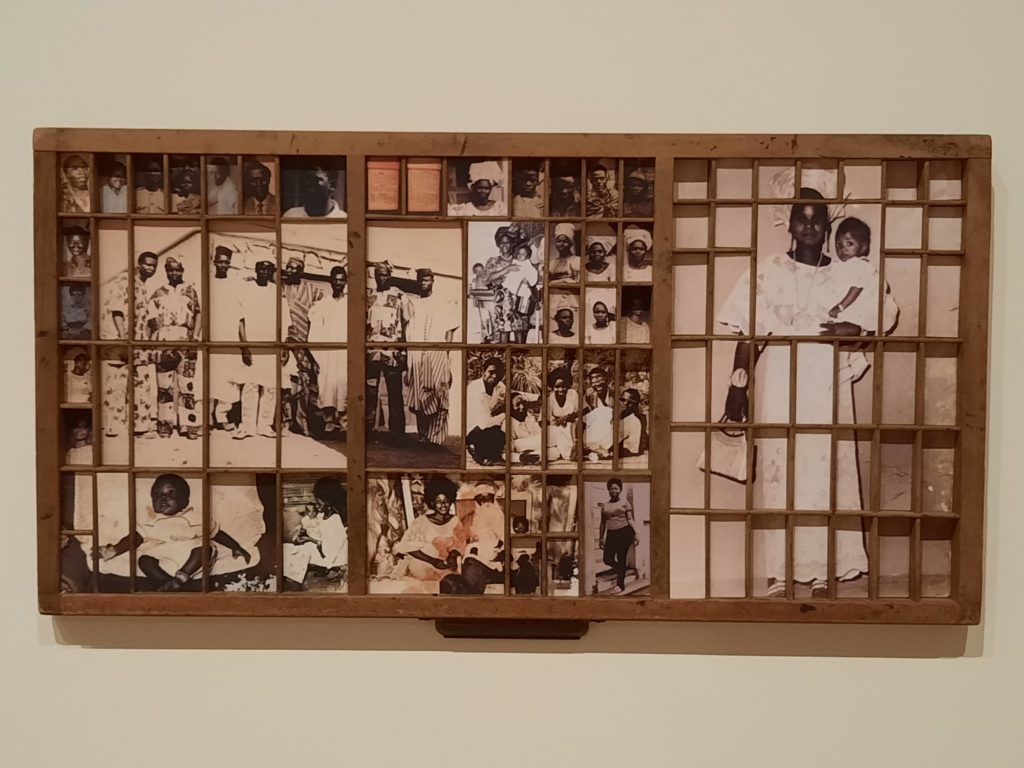

‘The Living Archive’ brings together artists who use archives as living knowledge systems rather than mere historic document repositories. Let’s face it, nothing is really neutral. Here, old images and documents are given new meanings by a range of artists. Délio Jasse will have you wondering why life for Europeans in Mozambique looked so… un-African. Malawi-born Samson Kambalu contributes two works. One highlights the expendable status of anonymous African soldiers from a library in Oxford. The other combines national flags and Kuba textiles to symbolise a global diasporic community.

Counter Histories is a place of reimagining. Windows onto different communities. African lenses on the colonial and post-colonial period. It’s like a collage of old and new, seen and unseen, personal and political (not that those two are so separate). This is where I really felt the breadth of the contemporary African experience, although one exhibition could only ever scratch the surface.

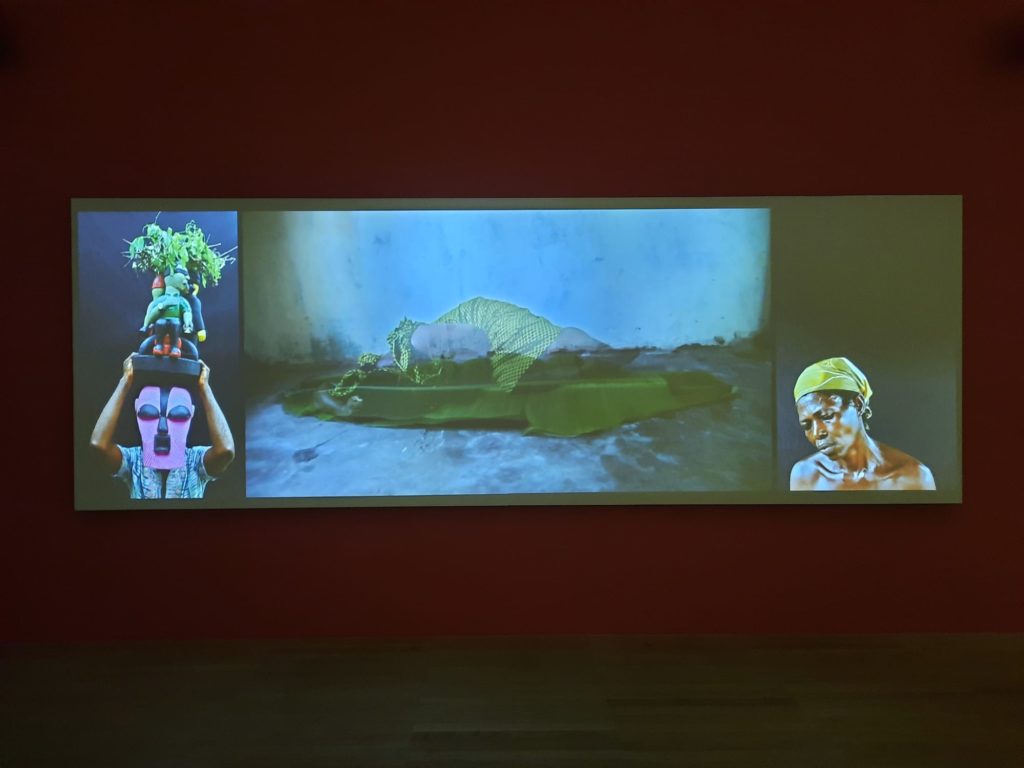

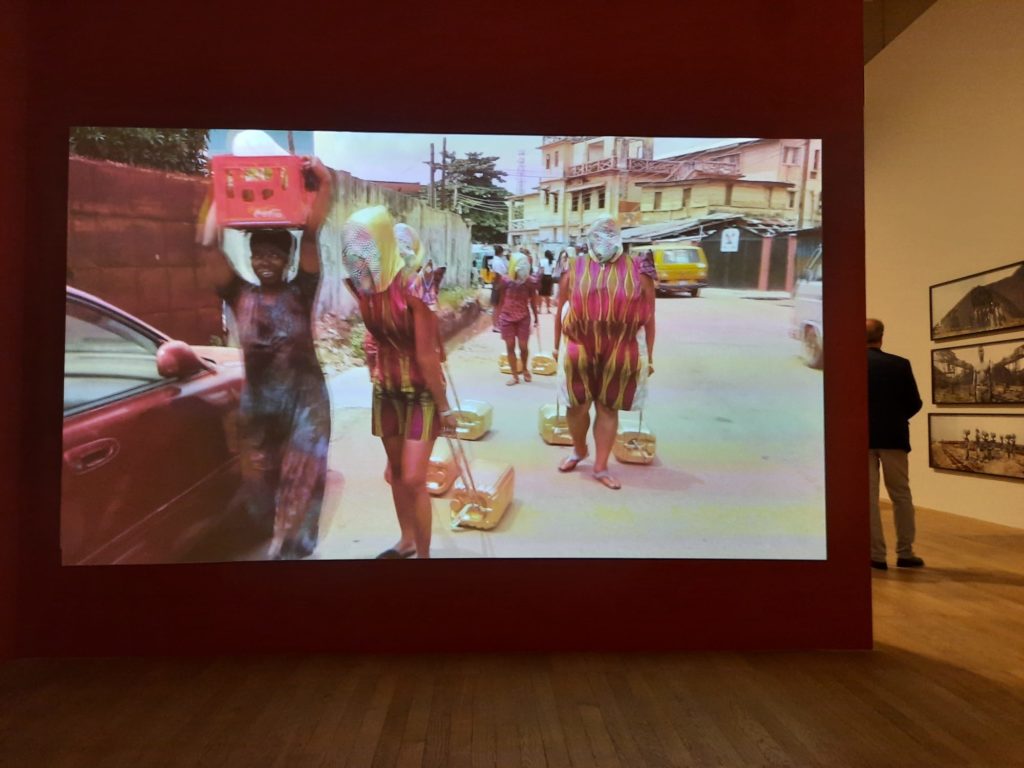

Imagined Futures

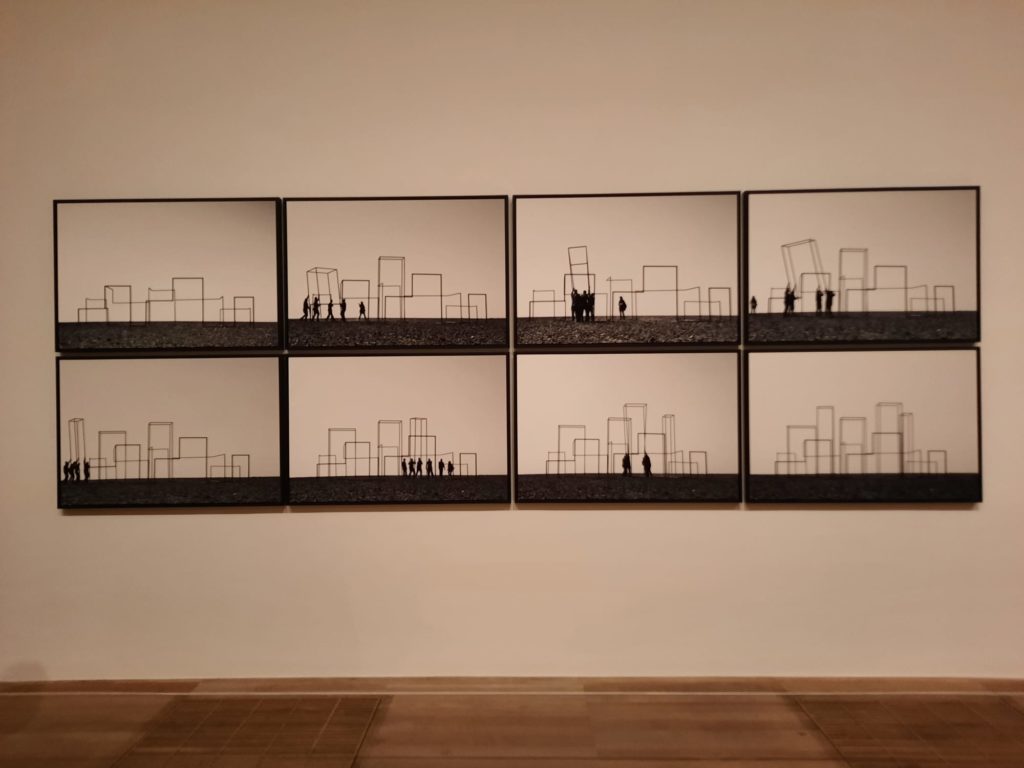

The final section of the exhibition has just one sub-theme (‘Shared Dreams’) and an epilogue. Here the artists consider various possible futures, responding to forces like globalisation, migration and the Climate Emergency. There are Andrew Esiebo‘s Nigerian cityscapes, documenting the intended and unintended uses people make of urban spaces. Aïda Muluneh‘s works are hyper-coloured, futuristic fantasies, abstractions almost of her inspiration: water and the struggle for women’s rights.

If there’s one work from this section I would like to pause on, it’s Afronauts, by Spanish artist Cristina de Middel. Buckle up, because the back story is a good one. In the 1960s a lone Zambian man, Edward Makuka Nkoloso, appointed himself director of the country’s National Academy of Science, Space Research and Philosophy. A footnote in Time in 1964 drew attention to his nascent space programme. Looking back on interviews and archival materials (see above for the non-neutrality of that), it’s hard to tell what’s serious and what’s playing up to the journalists. Nkoloso for instance recruited astronauts and put them through training including spinning them in oil drums and cutting ropes they were swinging on so they could experience freefall. De Middel’s series illuminates this strange history, exploring the boundaries of photography and truth.

If I focused in on this peculiar story, it’s perhaps because I struggle a little with bleak futures. Although stunning as artworks, and important, I found works which featured messages of warning (Fabrice Montiero – works in Senegal) or harsh current realities (Mário Macilau photographing workers on a landfill site in Mozambique) more challenging. I’m well aware this is my own cowardice, and doesn’t reflect the engaging, beautiful, political, urgent works in this final section.

Reflecting On Contemporary African Photography

So what does all this tell us? Firstly, as I said somewhere earlier, this exhibition is about trying to represent the breadth of a continent in an exhibition. You can’t fit it all in, any more than you could for any other continent. But I feel the curators have done a good job selecting artists, artworks and series. Together they show the variety and creativity of contemporary African photography. And of Africa. A plethora of cultures, languages, traditions, points of view. So many artists adapting old techniques and traditions or inventing their own. As an introduction for a primarily unfamiliar audience, it’s very good.

But A World in Common aims to be more than a survey. By grouping the works in thought-provoking themes, it creates a sort of ‘state of the union’. Despite all those differences outlined above, which threads do we find recurring from one artist to another? Identity and Tradition, Counter Histories and Imagined Futures are as good a way to codify these points of continuity as any. The themes put works in dialogue without confining them to overly narrow or reductionist boxes.

And many of these themes are global. Artists everywhere respond to and think through identity. We all share in whatever future is coming our way, whether we want to imagine it or not. What this exhibition does well is to bring to the surface a range of responses, illuminating what an African lens on these universal themes looks like.

Final Thoughts On ‘A World In Common: Contemporary African Photography’

Perhaps this is nothing more than my imagination and the time of day, but I have one final reflection. Or observation really. When I visited Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Nature, it was busy. People everywhere, a queue for the next time slot to get in. Granted, I saw A World in Common late on a weekend afternoon. But still, it was by contrast peaceful, serene, and had attracted a clearly appreciative audience.

That audience were what I might describe, using one segmentation model, as core cultural visitors: discerning, confident, independent and arts-essential. I heard robust conversation between groups, and noticed everyone seemed to linger. And this is the point that I wanted to make: this is not a blockbuster exhibition, but it is a very enriching one. It’s one to come to if you want to learn, to discuss, to be challenged. Leave a good hour at least so you can take your time, and then additional time to sit down with your museum pal(s) afterwards and talk through your favourite works, what excited you or what stumped you. The Tate have even created a chill out space outside which fits the bill: Common Ground.

So for my fellow core cultural visitors – this is one to see. It’s on for long enough that I may even go back again to see what I get out of it on a second viewing.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography on until 14 January 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.