Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed // Discover Liotard and the Lavergne Family Breakfast – National Gallery, London (LAST CHANCE TO SEE)

Two small, free exhibitions at the National Gallery explore artists in depth. Which will your favourite be between Pesellino and his sumptuous colours and Liotard’s portraits observed in soft pastels?

The National Gallery’s Latest in Mini-Exhibitions

It’s been a while since I’ve been to see the National Gallery‘s small exhibitions. As well as their bigger, paid exhibitions, the National Gallery maintain a programme of smaller offerings, often digging into a single artist or even a single work. I saw a single one-room exhibition last year, but I haven’t done a double bill since April 2022 (how time flies).

And yet a double bill of mini-exhibitions is a nice way to spend an hour or so, in my opinion. It’s not just that the exhibitions themselves are pleasingly self-contained. It’s also that it’s not a daunting task to see more than one, which sometimes results in interesting similarities, contrasts, and points for further discussion.

So today we are at the National Gallery to see two exhibitions. Both close soon, so you will want to make your way there in the next week or two if you also want to see them. First up (based solely on the order in which I saw them) is Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed. The restoration of two works on panel is a pretext for gathering together about as many of Pesellino’s works as you’re ever likely to see in one place. The second exhibition is Discover Liotard and the Lavergne Family Breakfast. Again an event (on this occasion the acquisition of a work by Liotard in 2019) is a pretext for bringing together a small exhibition showcasing an artist and his work.

Despite their completely different periods and artistic contexts, there are some similarities we can draw between the exhibitions. Both artists observed details closely. Pesellino worked in the Florentine tradition of careful preparatory drawing, and his scenes have a miniature-like richness to them. Liotard’s sketches and finished works reveal a good eye for costume, movement, and keenly observed scenes. Both have mastered their respective styles, and enjoyed renown as a result. If only Pesellino had not died young, we might have had more points of comparison.

Onwards now to look at each of the exhibitions in more depth. Let me know in the comments if one resonates with you more than the other!

Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed

You will have gleaned some details about Pesellino already from this post. He was a Florentine artist. He died young, leaving not too many works behind. And he was a master of detail and finely observed and constructed compositions. What you haven’t learned yet is that Pesellino is not an actual surname. The artist we know as Pesellino was actually Francesco di Stefano. His grandfather, also an artist, for some reason had the nickname ‘el Pesello’ (the pea), and so his grandson was ‘the little pea’. He made a reputation for small, highly finished works, and often worked in collaboration with other artists. Unfortunately, however, he died in a plague outbreak in 1457 at the age of 35.

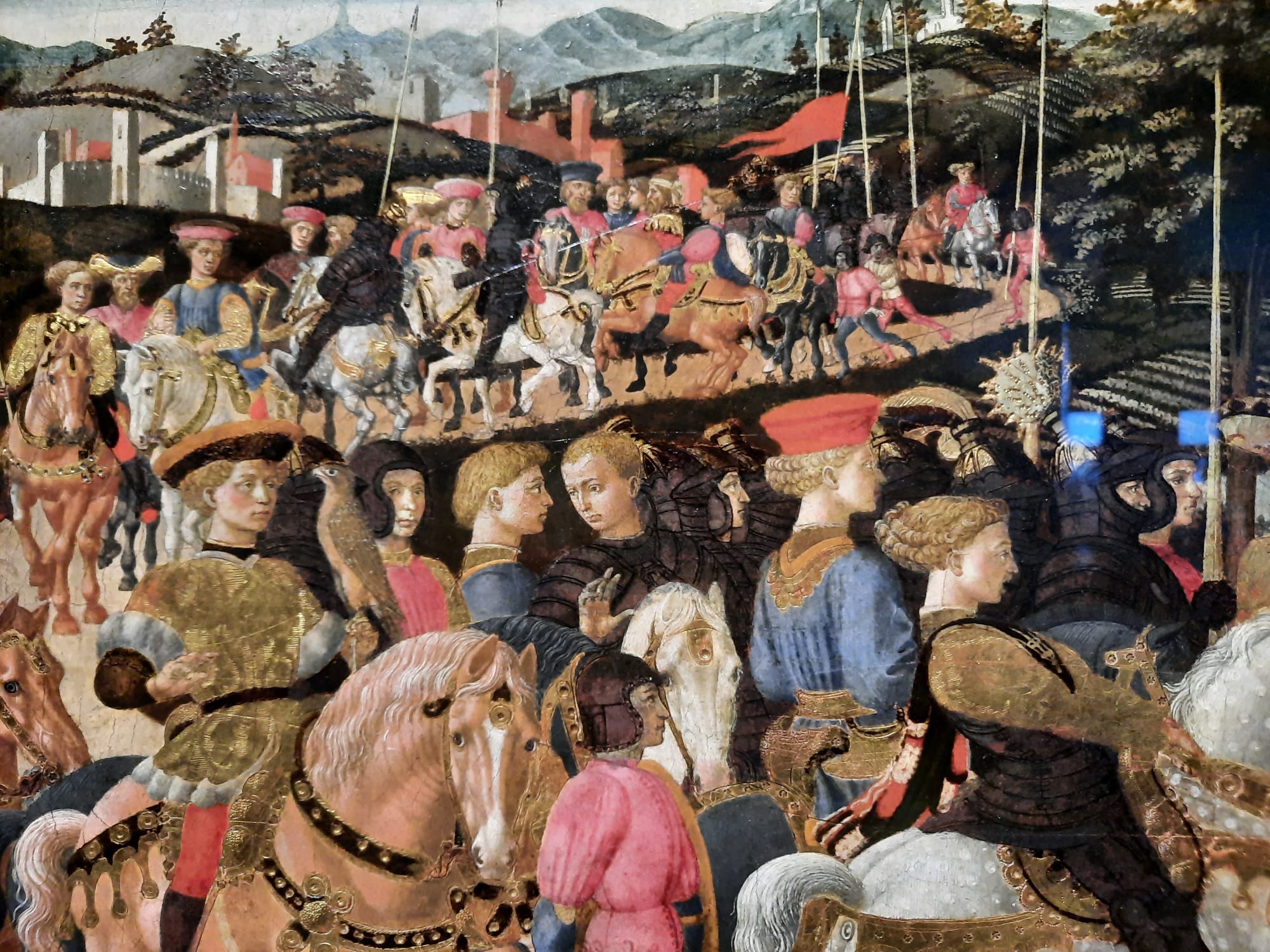

Given these facts, Pesellino did not leave behind enough works to construct a traditional retrospective. Instead, as I mentioned, the National Gallery have used the pretext of restoring two works on panel to bring together as much of a retrospective as is possible in the circumstances. The two panels, formerly from chests and depicting David and Goliath, take pride of place. They are remarkable, telling the story almost like a comic book, and with richly layered landscapes, soldiers, animals and other details. The National Gallery provide magnifying glasses so you can truly admire the artist’s skill.

The rest of the exhibition consists of the usual sorts of Renaissance subject matter. An Annunciation. A Madonna and Child. Assorted other saints. The less peopled the scenes, the less Pesellino’s particular talents stand out. His Madonna and Child are peaceful but plain (perhaps beause, like Donatello, Pesellino was looking for an image to reproduce for the mass market?). His scene of King Melchior sailing to the Holy Land, on the other hand, is mesmerising. The careful painting of the clouds and foaming sea. The busy composition teeming with ships, people, costumes, towns, even a dog on the foreshore. Your eye darts between the wonderful colours and the many small details. Although it’s a shame Pesellino’s artistic legacy was not greater, this exhibition is a fine tribute.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed on until 10 March 2024

Discover Liotard and the Lavergne Family Breakfast

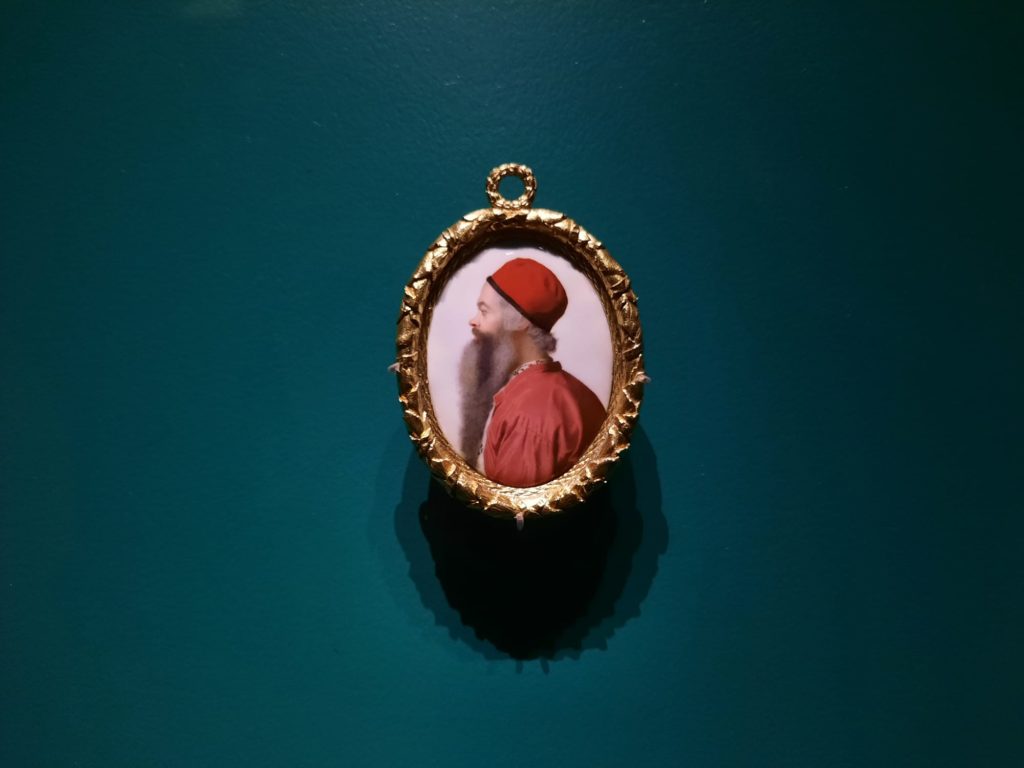

And now for our second exhibition of the day, Discover Liotard and the Lavergne Family Breakfast. I actually did discover Liotard a few years back when there was an exhibition of his work at the Royal Academy, so let me tell you what I remember. Jean-Étienne Liotard was an 18th century Swiss artist. He travelled extensively, including several years in Istanbul (then Constantinople in the Ottoman Empire). Upon his return he adopted Turkish dress and cultivated a persona as “the Turk” – an early PR ploy, perhaps. He was a master of pastels but also painted in oils. He was a popular portraitist, many of his sitters also adopting exotic Turkish dress to have their likenesses captured.

As I mentioned above, the National Gallery acquired an important work by Liotard, The Lavergne Family Breakfast, in 2019. Or I should say one of The Lavergne Family Breakfast(s). The National Gallery’s version is the original, a scene in pastels of a mother and child at the breakfast table, the little girl’s hair still twisted in curling papers. Liotard sold it to his patron Viscount Duncannon in 1754. Almost twenty years later he returned to it and made an exact copy in oils. This version is today in a private collection, and the two have probably not been seen side by side since the copy was made.

I really enjoyed this little exhibition. The two versions of The Lavergne Family Breakfast take pride of place, meaning you can take your time and see the differences in medium. The pastel version reflects the textures beautifully, particularly the woman’s soft powdered hair and shining dress. You can also see where some colours in the oil paint have faded, and reflect on how other paintings from the period might have changed. Behind the two works is a short loop where you see other examples of Liotard’s work, learn about his travels, and see porcelain and pastels of the type he used (and one set of porcelain he owned). Liotard is still not very well known in the UK and so it’s a nice introduction, with just enough information to build and store a picture of the artist, his works, and his big personality.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

Discover Liotard and The Lavergne Family Breakfast on until 3 March 2024

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.