The Cult of Beauty – Wellcome Collection, London

The Wellcome Collection’s exhibition The Cult of Beauty is a mirror reflecting back to us the importance we place on ever-changing beauty standards.

The Cult of Beauty

If there are two things that are certain when it comes to beauty, they are these. That what we consider beautiful changes with the times and in different cultural contexts. And that humans will go to great lengths to achieve the beauty standards particular to their time and place.

The Wellcome Collection’s exhibition The Cult of Beauty makes far more nuanced arguments on both these points. It does an excellent job of reminding us that what we consider to be beautiful today hasn’t always been thus. And that many factors feed into beauty standards. To do this, they have drawn mostly on their own collection stores, augmented with loans from other institutions. They then break the material down thematically, exploring different notions of beauty and the beauty industry before encouraging us to break free from beauty standards through three newly commissioned works. To get to grips with and then reject notions of beauty within one exhibition is potentially a big ask of an audience member. Let’s see how the Wellcome Collection managed it.

Just a quick note on accessibility before we begin. I found the Wellcome Collection’s accessibility measures very impressive. As well as a tactile path for visually-impaired visitors to follow, there are a range of ways of accessing the information contained within it: visual, sensory, and so on. There’s also a BSL and audio tour available, and ample seating inside. It stands out as the best example of accessible exhibition design I’ve seen in a long while.

The Ideals of Beauty

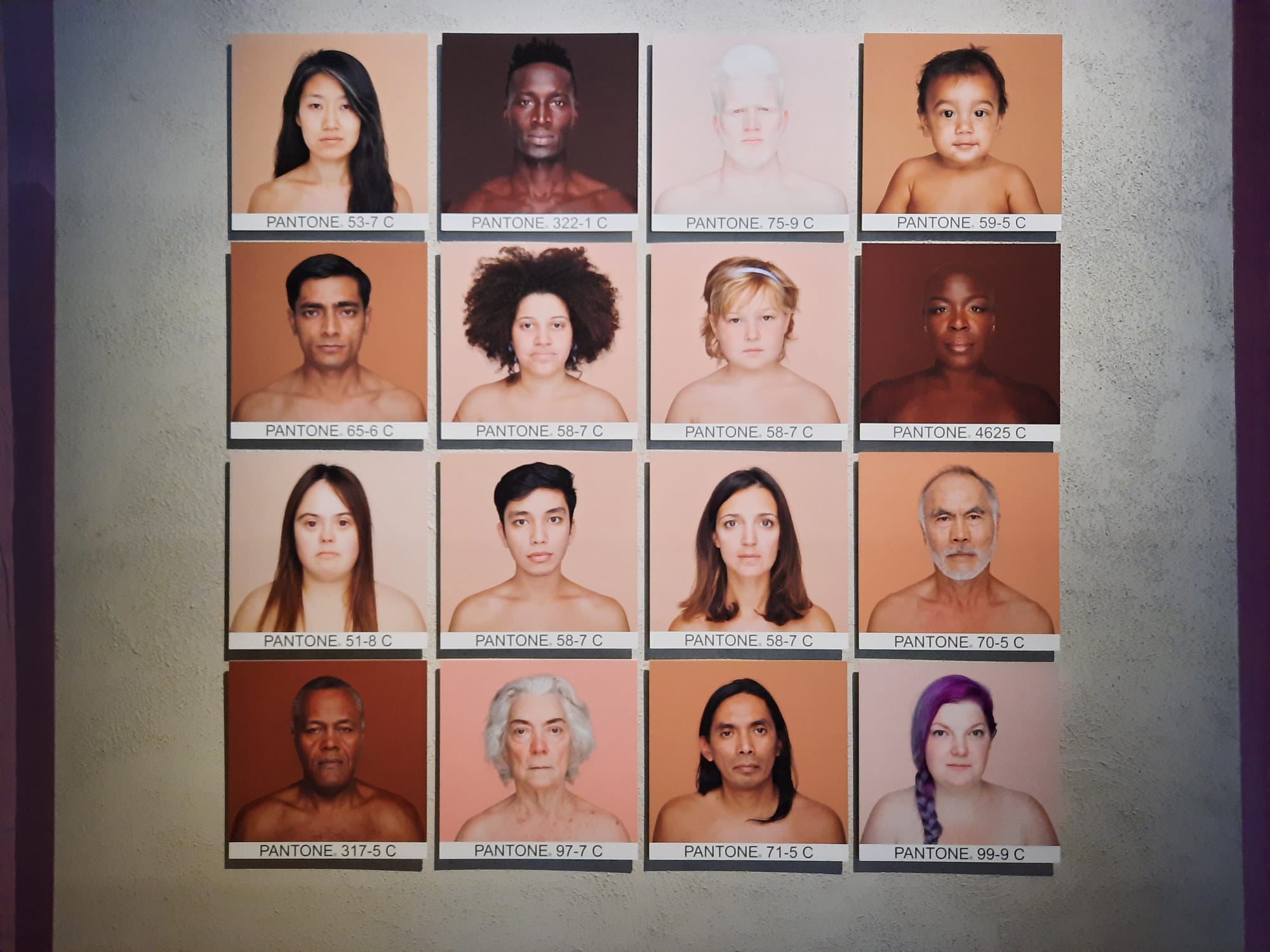

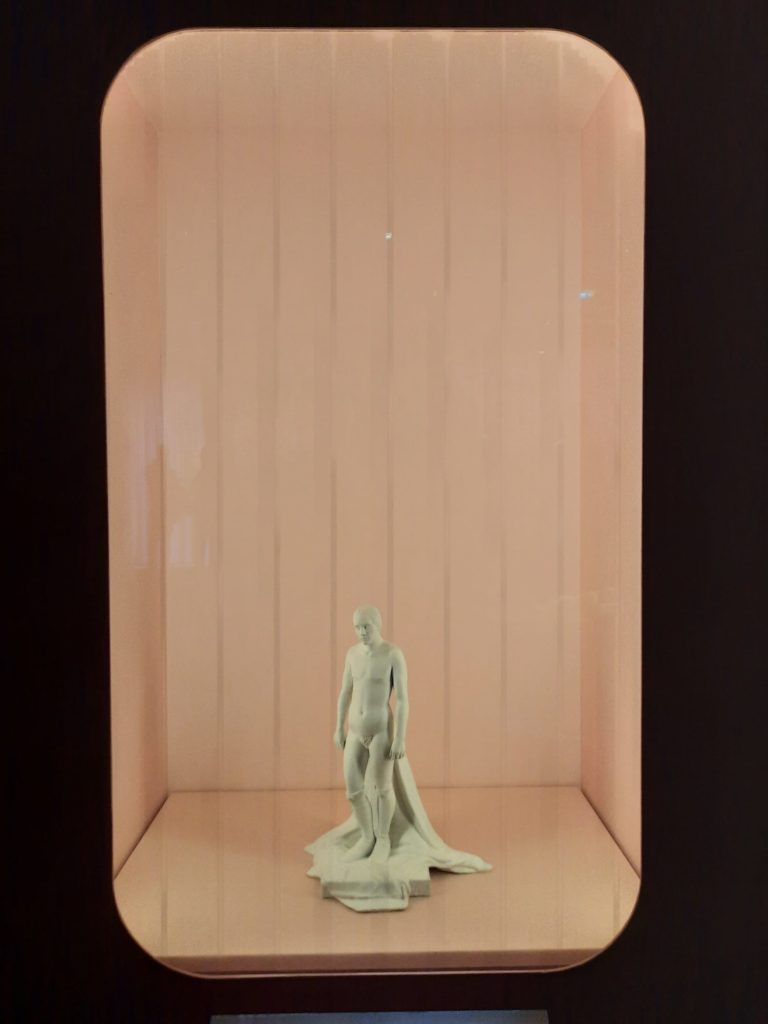

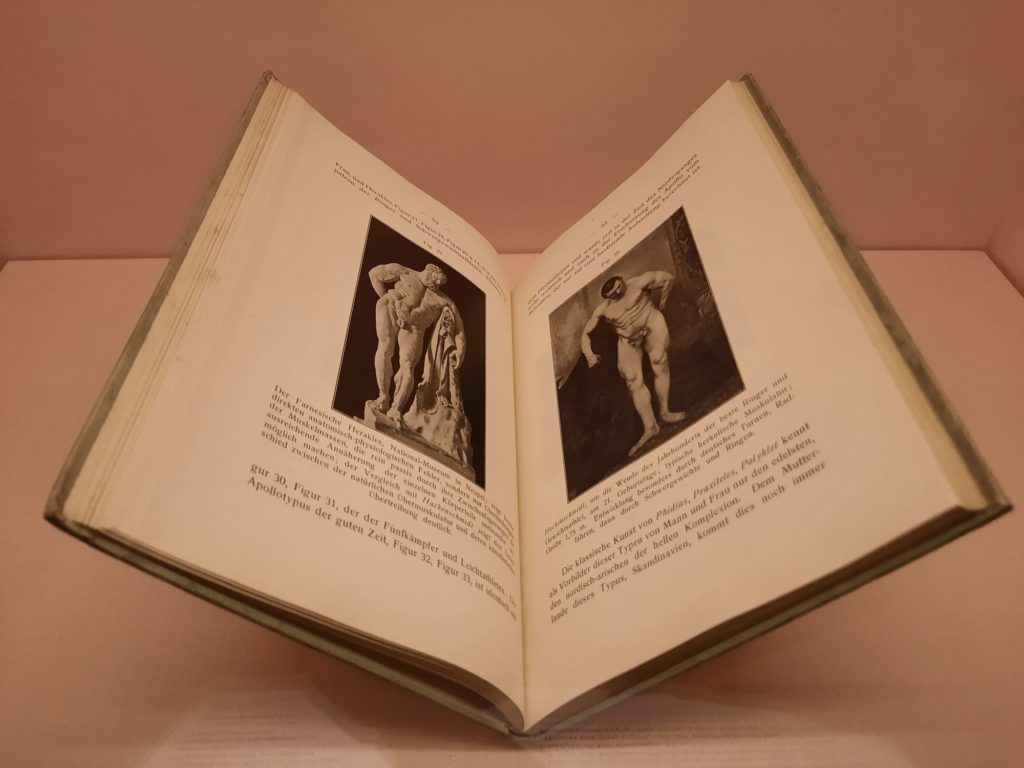

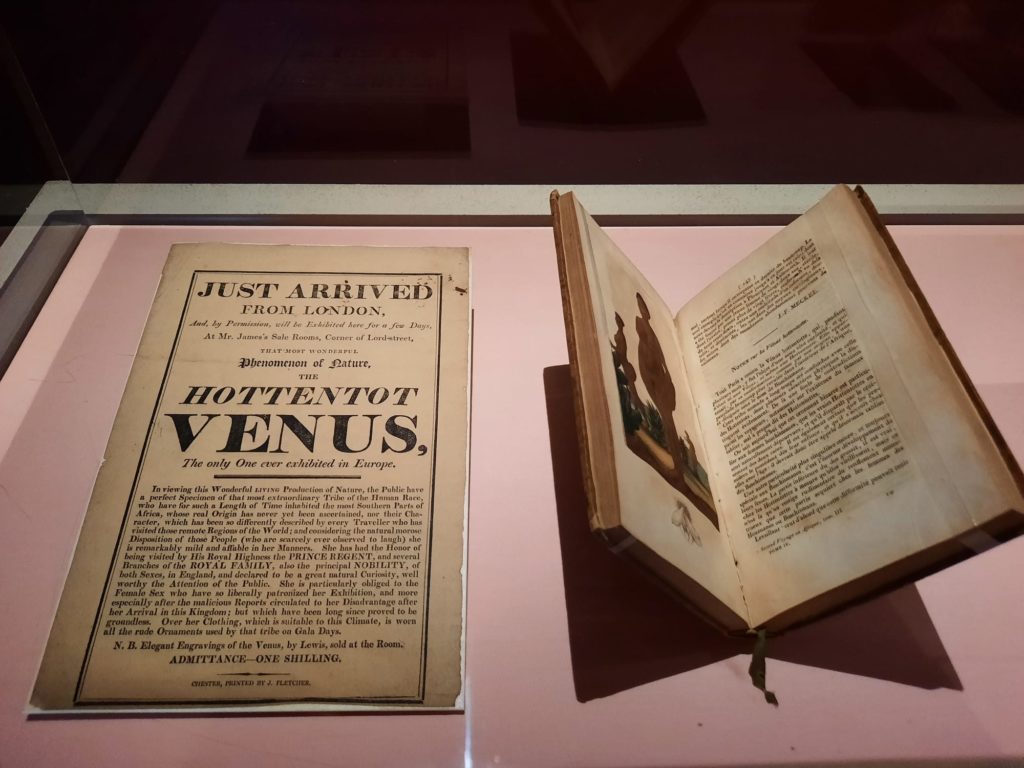

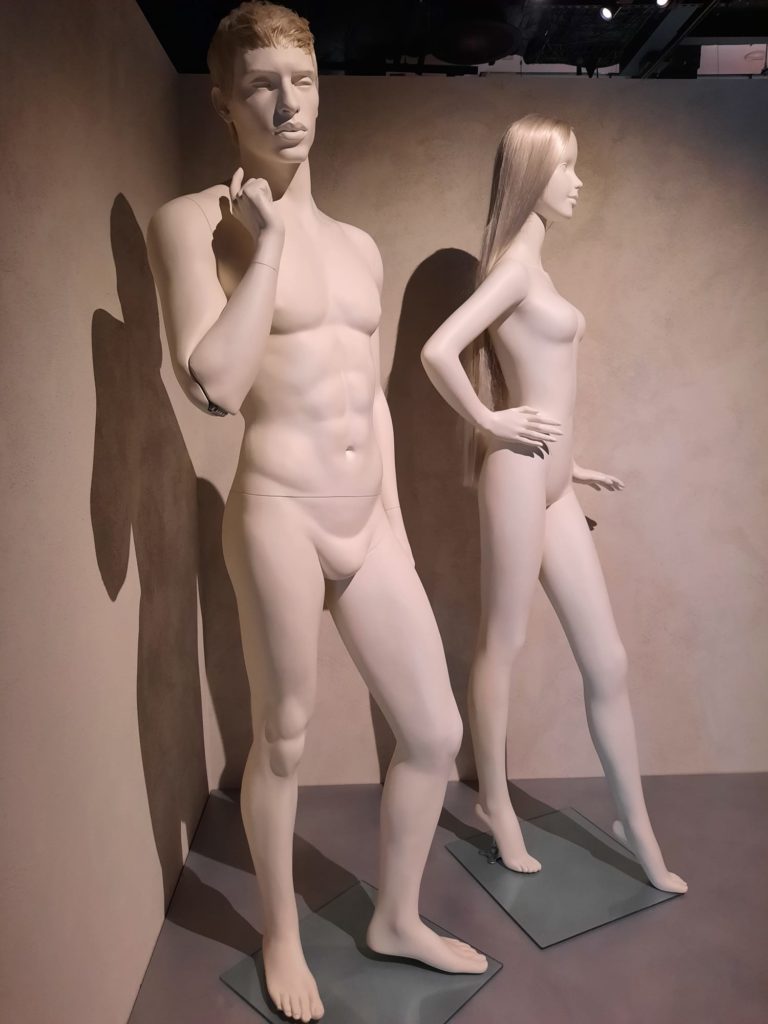

The exhibition’s opening section is ‘The Ideals of Beauty’. Rather than a chronology of shifting beauty standards, the curators have created a dialogue. Objects from different times and places sit together. A bust of Nefertiti. Classical statues, whiter and more ‘pure’ than their original polychrome selves. Corsets and moustache-tamers. Religious and secular objects.

What this combination does very effectively is to highlight all the factors which determine what is considered beautiful in any given time and place. That is to say beliefs around gender, race, status, religion, morality, age and health, for starters. It also introduces a sense of the futility of chasing beauty. You can ingest all the gold you want (a nice parallel is drawn here between a French noblewoman who more or less poisoned herself with it and contemporary gold-infused products) but will find in the end that beauty is fleeting and you may attain a standard only to find it’s yesterday’s news and fashions have moved on.

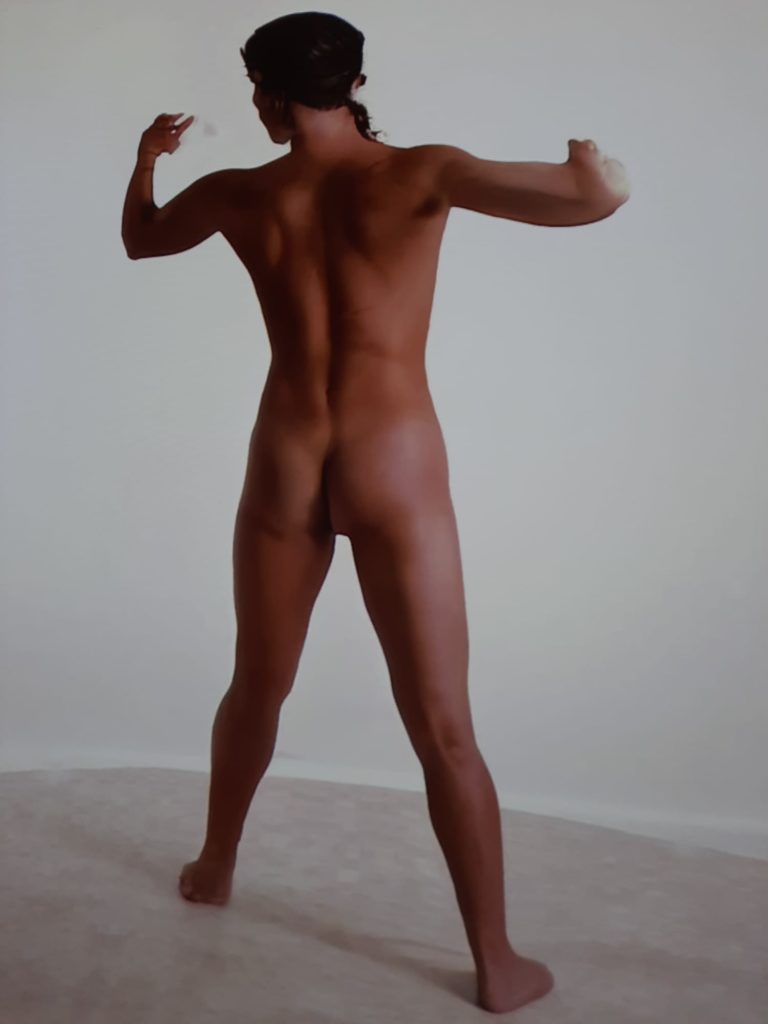

Contemporary art is introduced in this first section as a way of challenging and subverting norms. Works by artists including Carlos Motta and Cassils focus on their own and others’ non-conforming bodies. Positioning these works near a copy of the classical form of Hermaphroditus reminds us that, despite what we may believe, there has never been one single standard of beauty to aspire to. Further on, This Hair of Mine by Cyndia Harvey is well worth a watch to understand more about Black communities in London and their young women’s relationship with their hair.

The Industry of Beauty

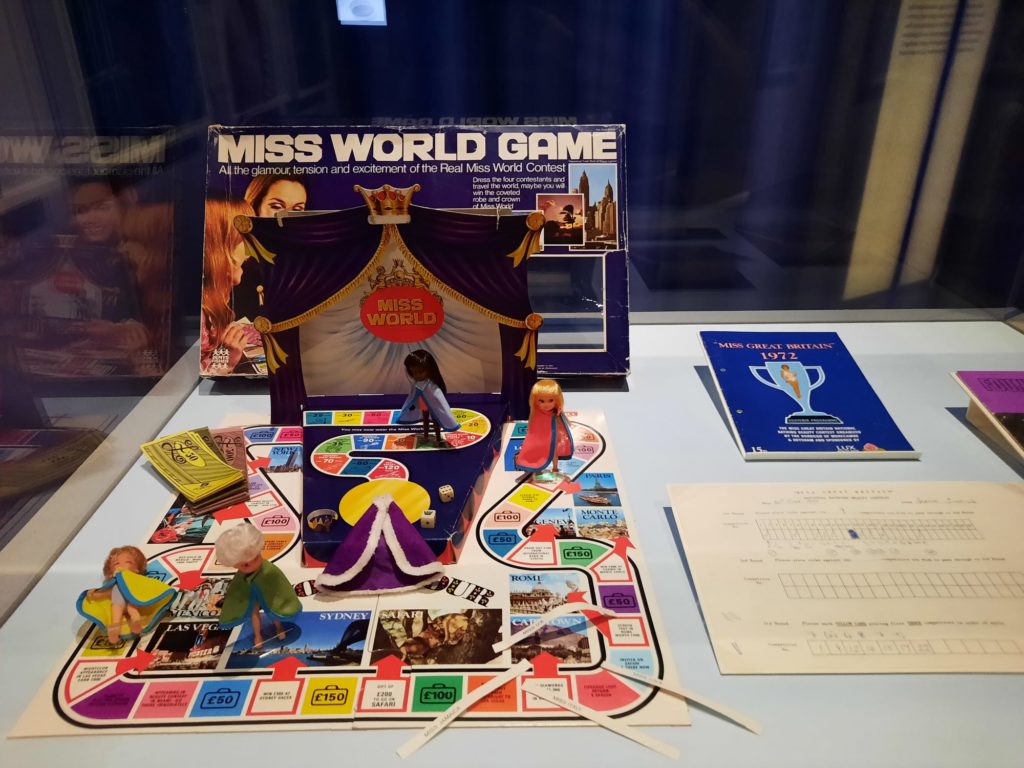

The next section looks at how our pursuit of beauty is commodified and commercialised. Like the section on beauty standards, it’s stuff that we sort of know. But it’s still somewhat shocking to see all the gadgets, creams and tools laid out in one place. And an interesting reminder of how beauty standards are not always as Eurocentric as we might assume. Seeing how products are developed for or marketed in different geographies is insightful.

One very interesting thread in this section is around how medical advances often filter down into cosmetic treatments. The corsets from the earlier section are an example of this. Electrotherapy was a treatment for tuberculosis but is now more frequently applied to bad skin. LED lights, now popular in face masks, originate in a NASA treatment to stimulate cell growth and wound healing.

This section of the exhibition dips into many different topics: accessibility, sustainability and inclusion amongst them. There is also a multi sensory display to enjoy. Beauty Sensorium: Renaissance Goo x Baum & Leahy recreates centuries-old recipes skin and haircare recipes and lets us see and smell them. This is a fun pitstop before the images I found the most shocking of all – a small section of contemporary artworks focusing on surgery (both gender-affirming and cosmetic). OK not all the works are shocking. Shirin Fathi’s are playful, Bharat Sikka’s are striking (particularly with the inclusion of the tissue removed during one individual’s top surgery). Zed Nelson’s images of plastic surgery in Brazil are enough to make you wonder why anyone goes through with it. Follow the signage to stay away from this section if you’re squeamish.

Subverting Beauty

And so we come to Subverting Beauty. Rather than an assemblage of objects and artworks, this section consists of three new commissions. Firstly there is a film, Permissable Beauty. Against a backdrop of stately homes like Petworth House and Hampton Court Palace are moving portraits of six Black Queer Britons. And I mean moving in both senses. Le Gateau Chocolat is one of the six; the others were new to me. Writer and performer David McAlmont takes inspiration from the Windsor Beauties (ladies of the court of Charles II) and also the Virgin of Guadalupe from the Wellcome Collection which opens the exhibition. It’s a beautiful film, all the more poignant considering the dearth of representation for Black Queer stories in our culture.

The next commission is a massive sculpture. (Almost) all of my dead mother’s beautiful things, by Narcissister, does more or less what it says on the tin. Her mother’s possessions form a large nucleus within the room, while additional materials on the walls explore the artist’s relationship with her mother, her ethnicity, and her artistic persona. It traces the weight of beauty ideals handed down between generations. It will speak to a lot of individuals who have undergone a process of deconstructing and reconstructing ideas of beauty.

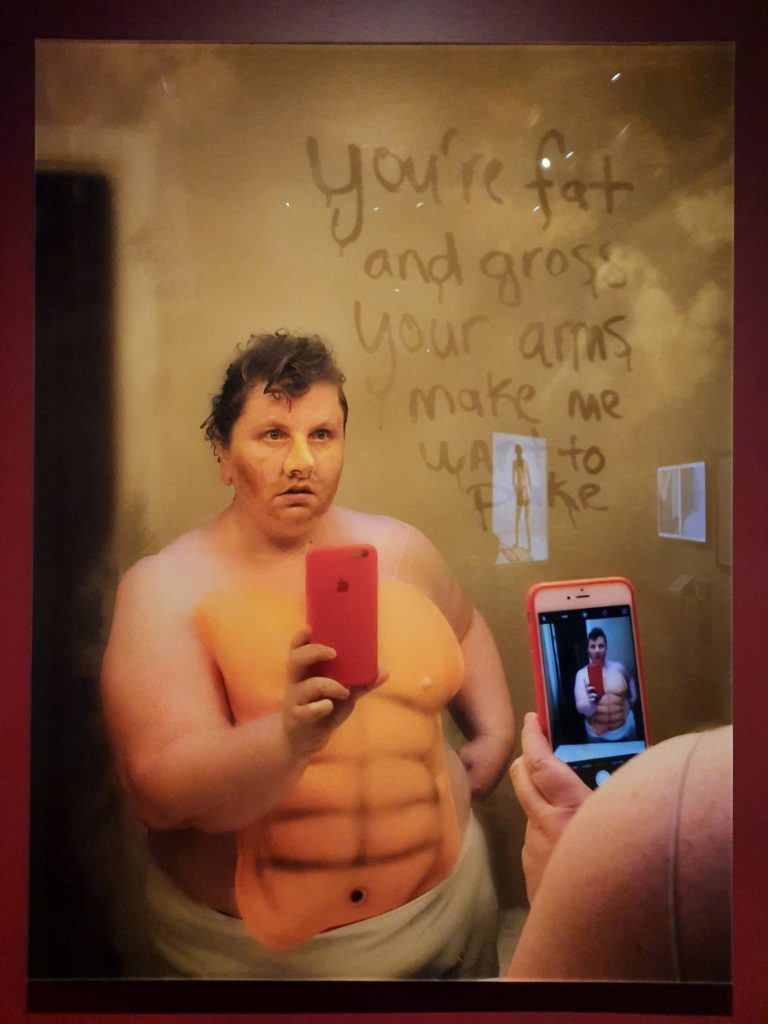

And finally to finish the exhibition we have Mirror, mirror on the wall, Beauty unravelled in the virtual scroll by Xcessive Aesthetics. This multi-media immersive work recreates an interesting space: the bathroom in a nightclub. A public space where people connect while they check and adjust their appearance. It leaves us on a hopeful note: as well as the dangers of beauty idealisation and expectation, there is community and connection here.

And so we come to the end of The Cult of Beauty. There’s a lot here, but the Wellcome Collection team have done a good job of breaking down complex topics into bite-sized chunks. Several of the themes would be interesting to expand further, but the exhibition is already large enough to try to take in in one go. It’s on for a while yet and free to visit. I really recommend it to everyone: whether you have struggled with beauty standards and self-image or are forever chasing perfection, there is material here to challenge and expand your worldview. Perfect for an institution which focuses on health and human experience.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

The Cult of Beauty on until 28 April 2024. More info here.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.