Entangled Pasts, 1768-now – Royal Academy, London

A thought-provoking and deeply reflective exhibition, Entangled Pasts, 1768-now looks inwards and outwards to examine the Royal Academy‘s entanglements with British colonial history over the centuries.

Entangled Pasts, 1768-now

“What does it mean for the Royal Academy to stage an exhibition in 2024 that reflects on its role in helping to establish a canon of Western art history within the contexts of British colonialism, empire and enslavement? Why now, and why does it matter? What were the conditions that led the Royal Academy, along with many other nationally significant institutions (including the National Trust, English Heritage, Fitzwilliam Museum, Tate and the National Gallery), so recently to investigate their own entanglements with Britain’s colonial pasts? What can art bring to the wider public conversation about history?”

Catalogue essay ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768-now: Art, Colonialism and Change’, Dorothy Price with Sarah Lea

I had very high hopes for Entangled Pasts, 1768-now. As a historian, museologist and typical left-leaning academic type, I have a great interest in projects to decolonise institutions and create open dialogues about the past. I come at this from a position of curiosity. And also believe in the power of reflecting honestly on the past to help us change the present and future. I wanted to see how the RA would approach this task. What angles would they explore (or not), and how far would they go? So with great optimism I headed to Piccadilly one Saturday morning to take a look for myself.

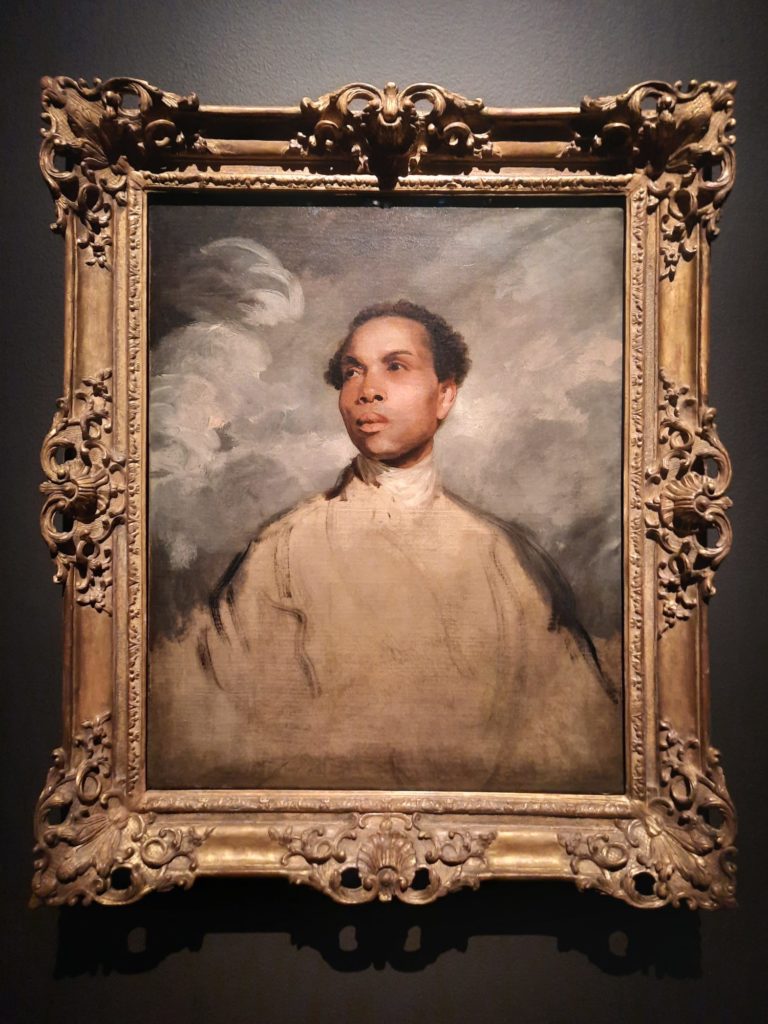

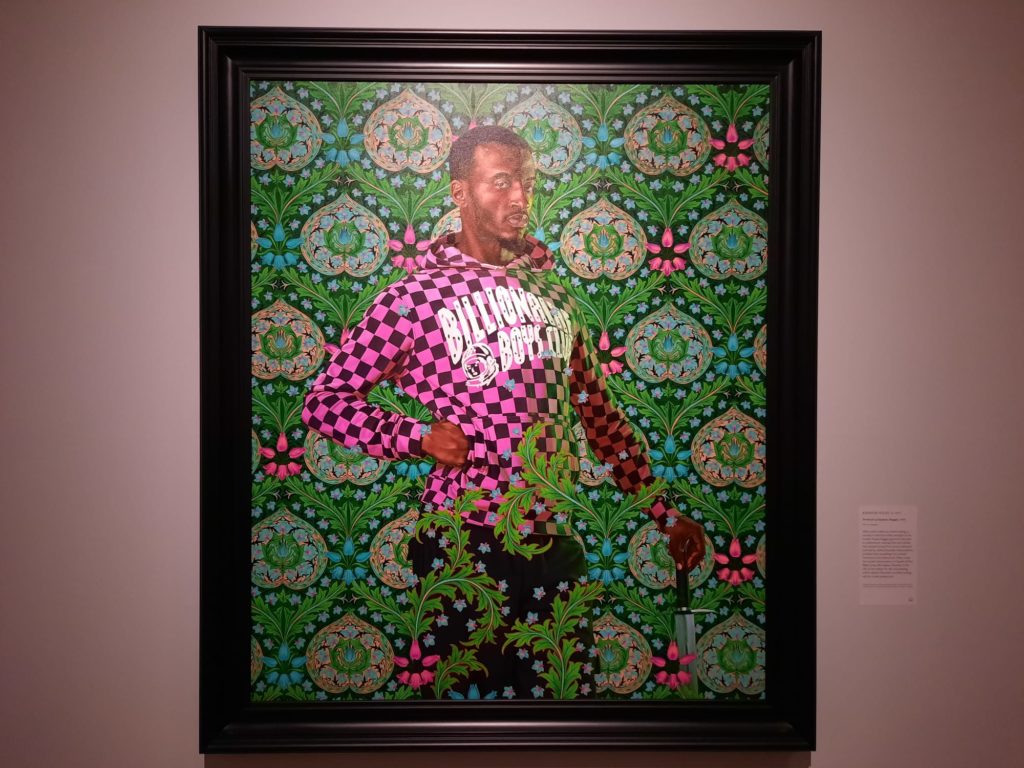

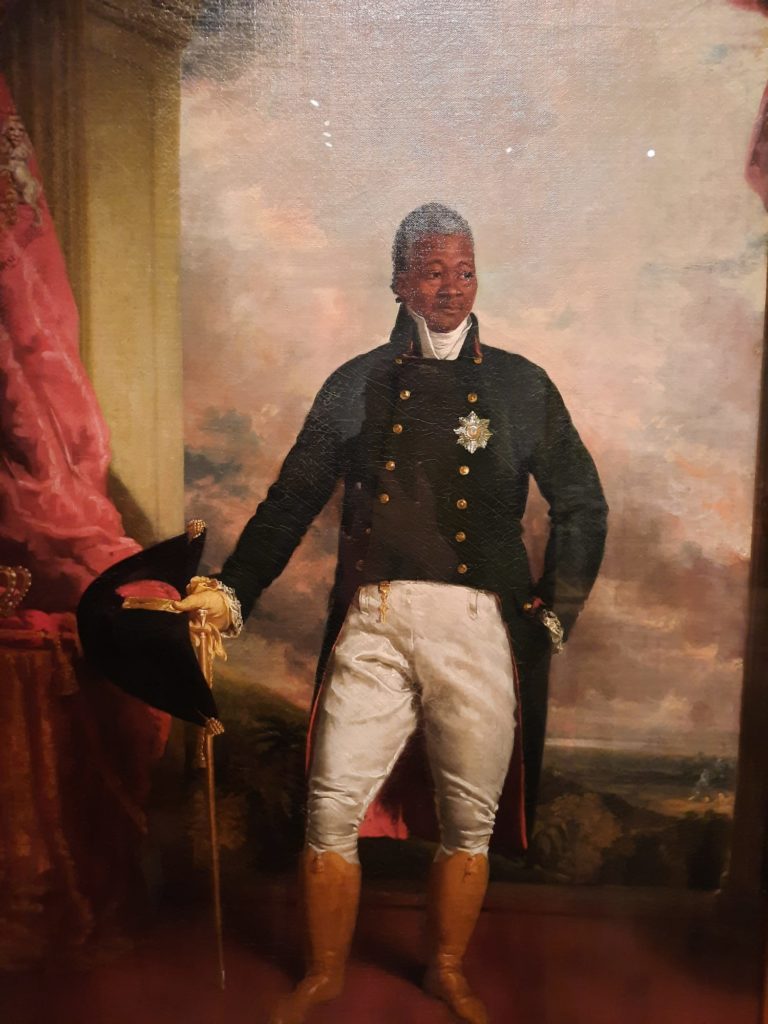

Reader, I was not disappointed. Entangled Pasts is an exciting exhibition from the outset. Entering straight into the octagonal centre of the RA’s main galleries (most exhibitions start off at the side), you are surrounded by portraits of Black sitters, with a bust of a Black man in the centre of the room. Mirrors cover several of the neoclassical busts above, amplifying the figures before us rather than the artistic lineage we take for granted. The sitters are a mix of named and unnamed individuals, and include a representation of Scipio Moorhead – a Black painter of whom no images survive – by Kerry James Marshall. As a statement of intent, this first space is clear and bold.

What I also appreciate about this exhibition’s approach is its restraint. This topic is so expansive, with so many potential avenues of exploration, you could fill many Royal Academies and still not be done. So the curators (the RA team initiated the exhibition and proposed external curators to shape it) have shown great restraint in limiting the selection to 100 works. They have also limited the entanglements under scrutiny to primarily the enslavement of African people, and connections to India via the East India Company. Both at an institutional level, and the entanglements of individual Academicians. This selectiveness allows the curators to delve into these topics in a meaningful way, and allows audiences to enter the dialogue without the volume of works and ideas becoming overwhelming.

Let us now traverse the different themes of the exhibition, to look at the content and the dialogue it creates.

Sites of Power

The first thematic grouping is ‘Sites of Power’. This theme looks at the period’s geopolitical background, and also takes in the artistic context. By this I mean the types of art which were popular in the late 18th-19th centuries, and how art worked. Patronage, the hierarchy of genres in academic painting, and the tastemaking power of Royal Academy exhibitions. Just like today’s Summer Exhibitions, the RA’s Annual Exhibitions were a chance to see the latest in art, and for the public and critics to give their views. Painters like John Singleton Copley and Benjamin West were at the forefront of a new genre of history paintings of recent events, giving us insights into the interpretation and reception of geopolitical forces.

There are some fantastic works on display here, particularly Copley’s 1778 Watson and the Shark on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It’s a perfect example of the dramatisation of recent historical events (in this case a 1749 shark attack in Havana). But the inclusion of a Black figure at the apex of the scene and the contemporary reception of this choice (reading the figure as passive or ‘idle’) is telling.

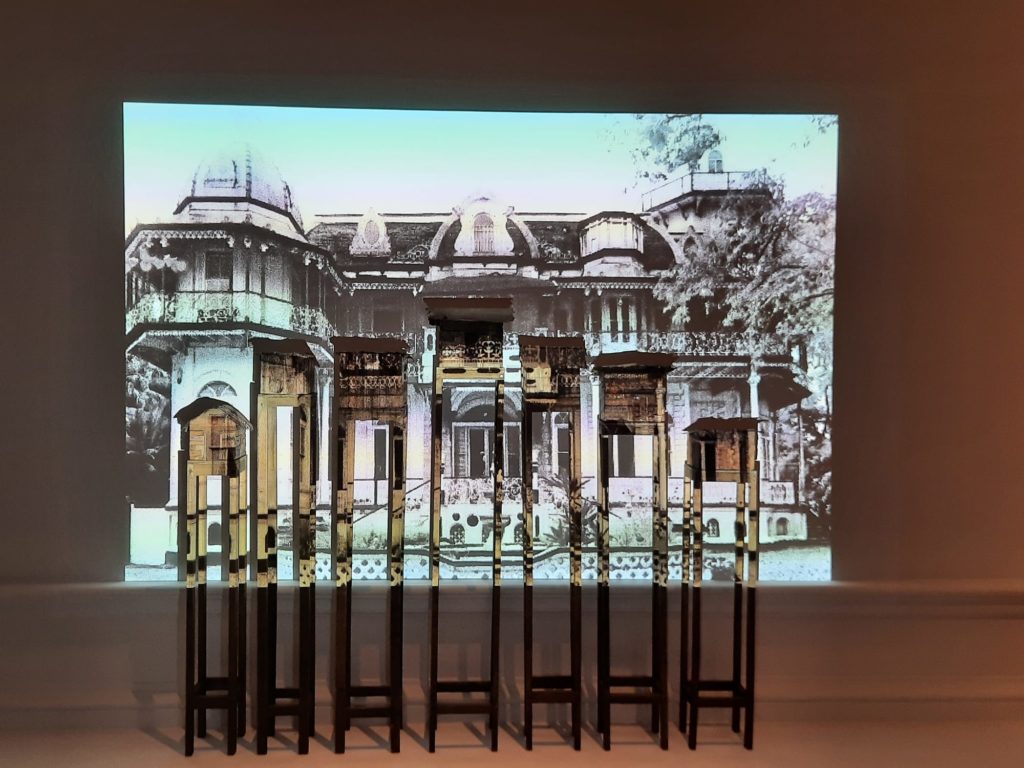

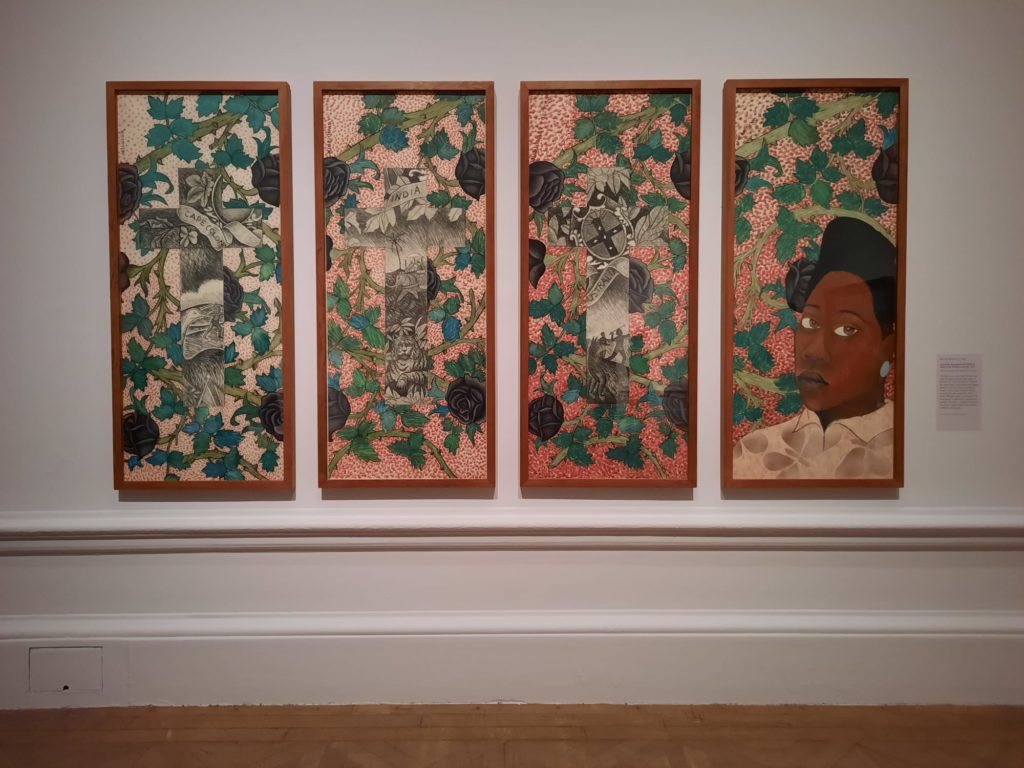

It’s also within this theme that we encounter the greatest focus on the Indian Subcontinent. Works by Western artists borrow techniques from Mughal miniature painting. Contemporary artists like the Singh Twins reflect critically on the complexities of colonial exchange. As I said earlier, I see the curator’s selectiveness as the reason the exhibition is so successful. Whatever the intention of this second focus, for me it was a reminder of how many entanglements and echoes tie us to the past. And also of the reach of the trade in enslaved people beyond the Atlantic triangle, for instance in Indian manufacturing or the movement of indentured labourers after abolition.

Beauty and Difference

The section entitled ‘Beauty and Difference’ examines aesthetic norms through the mass media of the day. By looking at representations of Black and Brown bodies, the visual language of the Abolitionist movement, and how far-flung colonial spaces were represented, we learn a lot about the people and politics which created these images.

Firstly let’s set a little more historic context. 1768, the year in the title, is not a randomly chosen point in history. It is the year of the RA’s foundation. This places it firmly in the Age of Enlightenment, a time in which Western scholars and philosophers pursued truth and reason through evidence-based knowledge. Only, as we know, hierarchical systems of knowledge are not without inherent biases which, if unchecked, allow racist power structures to flourish. The enslavement of African people was vigorously justified on apparently scientific grounds. 1768 was also very early in the Industrial Revolution. And during the 19th Century, as the Royal Academy established itself, the British Empire grew to unprecedented size.

All of this history is swirling around in this section of the exhibition. We see how a figure of a Black Venus sanitised the unimaginable horrors of the Middle Passage. There are images of harmonious exotic shores: like a sort of PR-campaign for Empire. And one really telling work is represented in the form of a scaled-down Minton version. The Greek Slave propelled Hiram Powers to artistic stardom in the 1840s. An elegant, noble figure in chains, she inspired a host of artistic and poetic responses from Abolitionists. But what the sculpture makes clear is that contemporary audiences found slavery easier to empathise with and denounce when the enslaved person looked more like them.

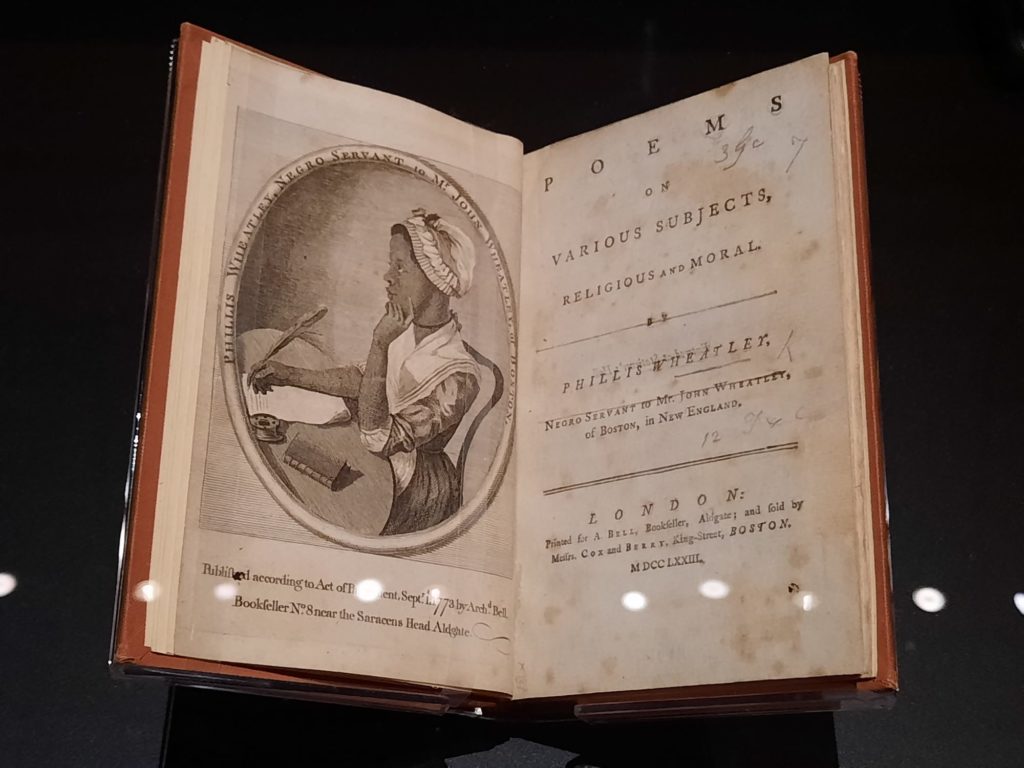

This section captures wonderfully the multiple voices of the period under review. And importantly, Black voices are also represented. We see an example of a volume by Phillis Wheatley, the first African-American to publish a book of poetry. And I was delighted to see a familiar work, Lessons of the Hour by Isaac Julien. This meditative film on Frederick Douglass drew a sizable crowd during my exhibition visit.

Crossing Waters

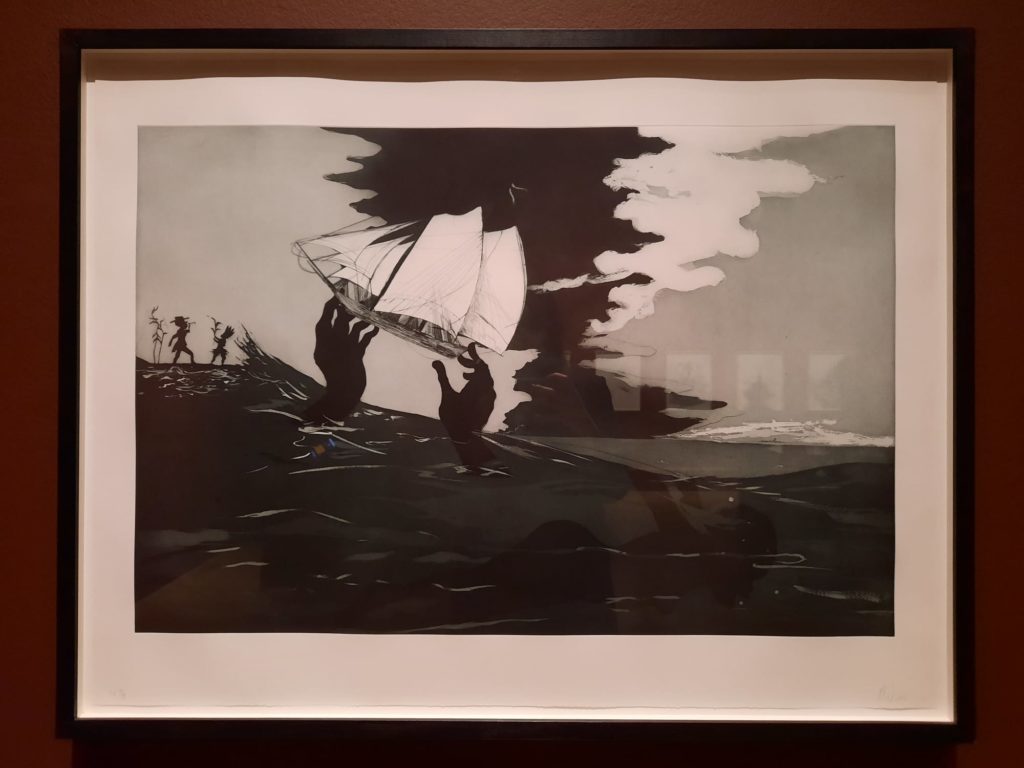

And finally we have ‘Crossing Waters’. This grouping takes the Middle Passage I spoke of earlier, and connects the exhibition’s themes back to the present. And at this point visitors have already seen the majority of Entangled Past’s 100 works. The finale is more about immersive spaces that create parallels and explore the ramifications of those entangled legacies.

This is a space for reflection and mourning, and incorporates a higher percentage of contemporary art than elsewhere. Although a couple of Turners stand in for that much more confronting painting he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1840: Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On). That particular work is too fragile to travel, although we did see a representation of it in another exhibition.

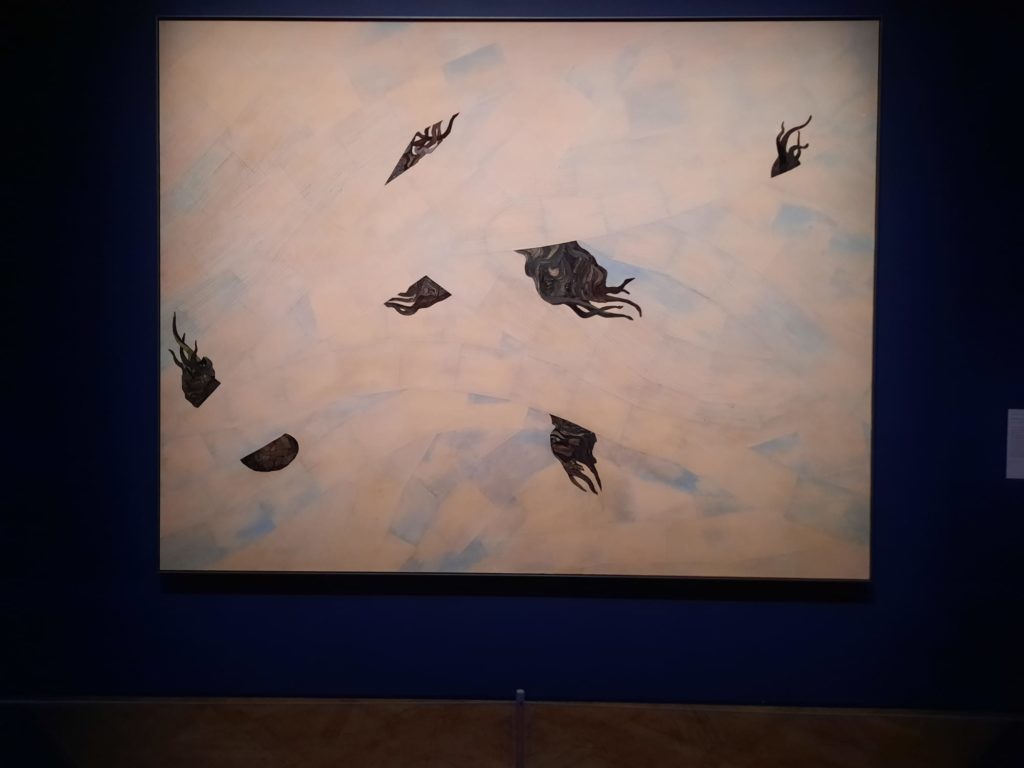

But back to the contemporary art. There are some really confronting works here, but this culmination of the exhibition is so important. Seeing El Anatsui’s Akua’s Surviving Children between Ellen Gallagher‘s depiction of the imagined kingdom of Drexciya and Frank Bowling’s Middle Passage is an exceptional bit of curation and exhibition design. I couldn’t bring myself to watch much of John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea, but appreciated how it brings together the history of slavery and colonisation with the environmental crisis.

From this harrowing gallery we then step into Lubaina Himid‘s Naming the Money across two rooms. Brightly painted figures fill the spaces, with an audio accompaniment. In walking around them, we realise each of them wears their story on their back. Their real name, their given name, what they did and what they do now. Their personhood, obscured behind the choices imposed upon them through the process of enslavement. Himid draws a connection here to today’s migrants and asylum seekers, through the reconciliation of different identities forged in very different circumstances.

And finally, the very last room is a call to action. Visitors pass between two works which remind us that our society, our power structures and symbols, are not neutral. On the left is Yinka Shonibare‘s Justice for All. On the right, Olu Ogunnaike reimagines Trafalgar Square’s fourth plinth in discarded exotic woods. Justice on the one hand, art itself on the other. An exhortation to think more deeply about who is represented, who participates, and how these entangled histories affect us all.

Final Thoughts on Entangled Pasts, 1768-now

So. What an exhibition. And yet, this is ultimately a starting point. Institutions in the UK are only just beginning to open up a dialogue about their pasts. To decolonise. There are many for whom this is an uncomfortable or unwelcome process. They’re not likely to enjoy this exhibition as much as I did. But the RA’s openness about their process, their journey, and the wider context into which this exhibition fits, makes it an exciting and invigorating moment.

Art isn’t neutral. Even history or landscape paintings, as we’ve seen today. History itself isn’t neutral. Neither are our institutions, our symbols, our understanding of our shared culture. The events of 2020, from the pandemic to the Black Lives Matter Movement, reminded many of us just how much traditional structures of power benefit some and disadvantage others. They also sparked many moments of reflection, like the one that led to this exhibition, which will hopefully pave the way to a more inclusive and just future.

I’m going to leave you with another quote. But before that, please allow me to encourage you once more to see the exhibition for yourself. It’s a great example of bold choices, great artwork selection, impeccable design, and meaningful subject matter. I only hope I integrate what I learned into how I understand the world and my place in it.

“One of the most powerful ways in which we might activate a decolonial mode of looking and thinking is by bringing historical and contemporary artworks together in a new visual conversation that illuminates both. What we hope this exhibition might offer, through time spent with artworks that embody the complexity of these histories, is a forum for acknowledgement, reflection and imagination – a place to inhabit the past together, to discover individual responses to these moments seen through the eyes of artists, to feel the reverberations of images and ideas down the centuries, and to question them.”

Catalogue essay ‘Entangled Pasts, 1768-now: Art, Colonialism and Change’, Dorothy Price with Sarah Lea.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 5/5

Entangled Pasts, 1768-now on until 28 April 2024. More info here.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.