Museu Frederic Marès, Barcelona

My pick of Barcelona’s museums is the Museu Frederic Marès, the wide-ranging personal collection of a local sculptor.

Eclectic Museums: Like a Siren’s Call to the Salterton Arts Review

Like many major cities, there are more museums in Barcelona than one could ever hope to see in a long weekend. Hell, I’ve been in London for over a decade and I’m still working my way through the museums here. I outlined in my Barcelona long weekend guide a few of the options and my recommendations. But as I read through my guidebook ahead of my trip I knew there was one that I had to see.

Here is the description that had me hooked: “Marès, a 20th-century sculptor of civic statues, was a compulsive collector who bequeathed to Barcelona an unusually idiosyncratic collection of art consisting of work from the ancient world up through the 19th century.” Beautiful courtyard, flanking the cathedral, yadda yadda. But it was that phrase that piqued my interest.

Why? Well, I love an eclectic museum. For me a really personal, strange collection beats a perfectly curated but dull one any day. I am not without compulsive collecting tendencies myself (very toned down compared to Marès, don’t worry) so the psychology of it intrigues me: why people continue to acquire beyond all norms or reason. Compulsive collectors also tend to collect things that other people overlook, which frequently makes the end result fascinating. This doesn’t always mean I love them – for instance Bruce Mahalski and Viktor Wynd, both collectors since childhood, have established ostensibly similar personal museums. One I liked, and one I was less comfortable with. But both were certainly unique and thought-provoking.

But we’re not here to talk about other collectors: today is all about Frederic Marès.

Introducing Frederic Marès

I’d never heard of Frederic Marès, so I wouldn’t be surprised if you haven’t, either. Born in 1893 in Portbou, right on the French border, Marès’s family moved to Barcelona when he was ten years old. He studied art in Barcelona, also travelling abroad several times. Soon after graduating, Marès began a career as a university professor, a post which he held until the 1960s. Presumably this provided a steady income, supplemented by various commissions for civic sculptures.

I didn’t know this at the time, but some of the sculptures leading up from the Plaça d’Espanya to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in Montjuïc are his work. His first public commission dates to 1919: at this time, as well as teaching art, he was sculpting in the workshop of artist Eusebi Arnau. In the 1920s he moved into monumental sculptures. His work can also be found at the Plaça de Catalunya at the top of La Rambla. He was also involved in restoring artworks and buildings in the wake of the Spanish Civil War.

But despite these surviving examples of his work in notable spots, Marès is perhaps today more remembered for his collection than his work as a sculptor. His collection, started as is so often the case in childhood, first gained publicity in the 1940s. It was in 1944 that he wrote a will bequeathing it to the city of Barcelona, shortly after a first public exhibition. He rented space to display his collection in 1946. It grew from four rooms to three floors of a building between 1948 and 1952. The collection had taken more or less its current shape and size by the 1970s: Marès lived a further twenty years, dying in 1991. The Museu Frederic Marès moved into its current spot in 1999.

Museu Frederic Marès

The museum’s current spot is actually a rather interesting place in its own right. Part of a jumble of old buildings abutting Barcelona Cathedral, it was once a seat of the Spanish Inquisition. There’s only a worn coat of arms which attests to this history today. Unusually, there’s also an internal window which looks into another museum, the Museu d’Història de Barcelona. Sort of a museum two-for-one. This latter museum is the subject of our next post.

So as a historic building, the Museu Frederic Marès has an idiosyncratic layout to match its idiosyncratic contents. You start on the ground floor, circling aninternal courtyard. After a quick detour downstairs, you head up to two further floors. I got confused a couple of times by blind corners and had to backtrack to see things I’d missed. But staff were generally on hand to ensure visitors were going more or less the right way.

The ground and lower ground floors are packed with medieval sculptures. And when I say packed, I mean packed. More crucifixions and Madonna-and-childs (a grammatical nightmare but go with it) than you could shake a stick at. So many, in fact, that they start to look a little abstract: their religious intention diluted by the shape so many of them make together on a wall.

Medieval Art A-Plenty

In some ways it’s like a counterpoint to the Romanesque collection of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The latter has a load of frescoes ‘rescued’ from churches around the Pyrenees and Catalonia. And here is the portable art: the wooden sculptures, reliquaries and altarpieces. Together, the two institutions probably have many complete church interiors. In some ways it’s a little sad to see how much of this sacred art is in private hands. Quite how some of the more monumental pieces – like the church arches displayed on the lower floor – made it into private hands is probably quite a tale.

But it is most certainly impressive. There is no doubt Marès cared deeply about this very local type of art. As I wandered around, I imagined to myself that he probably felt he was saving it from destruction or neglect. More on the psychology of collecting a bit later. And as long as we’re in the realms of ancient and medieval art, the collecting makes sense. A sculptor gathering a reference collection of local sculptural specimens. Fine, right? It’s as you make your way up through the floors that the sense of the collection gives way to truly obsessive collecting.

The Collection Diversifies

It was in the room of hundreds of keys that I started to think “this is brilliant”. Remember, eclectic and unusual collections are my jam. A room with not just hundreds of keys, but an unnecessary number of bedwarmers and helmets? Wonderful. We’ve arrived in the metalwork section of Marès’s collection. On the upper floors the collection is divided by type of object, with a preference for grouping things by material. Paper, ceramics, metalwork and so on.

And this is the part where the collector’s eye comes into it. Some of the collections were, I have to say, a little mundane. Stamps? Boring, anyone can collect those. 19th century découpage? Excellent, show me more! Fans? Alright, others have done it. Clocks where the eyes are cut out and swivel in time with the movement? That’s what I’m talking about! It’s those sorts of objects which are little historic survivals on their own. Frequently discarded as worthless or tacky. But a group of them together starts to tell us something about a moment in time where this was a fashion or a hobby. It becomes delightful, the details and differences fascinating.

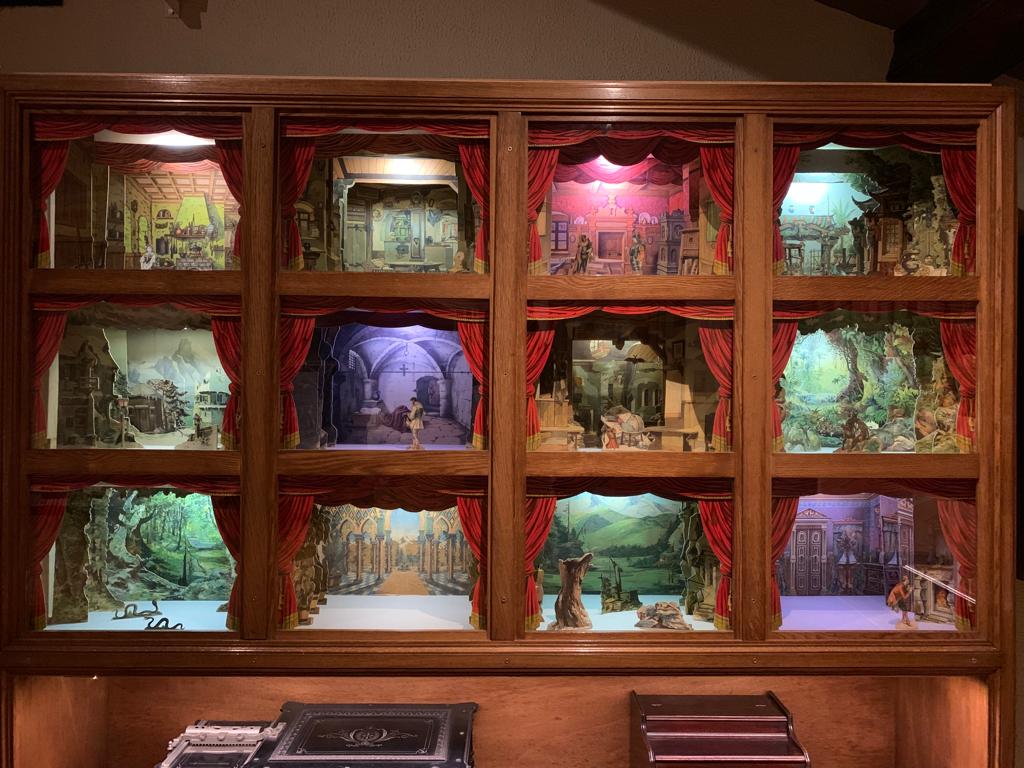

And this pattern is repeated over and over. Marès collected in so many different categories. There’s still a bias towards religious objects: portable votive objects, little saints made of seashells and so on. But there are also chatelaines, cigarette cards, hat pins. There are old toys, early photographs and Christmas nativity figures. Don’t forget about the ceramic plates, majolica tiles and cigar bands. Many of the collections are large enough to have been someone’s pride and joy. Together it’s a glorious cacophony and a celebration of collecting itself. A collection of collections. A meta-collection, if you will.

Which brings us on to an interesting topic.

The Psychology of Collecting

There are many different reasons why people collect things. And a spectrum upon which they do it. Marès was quite far along one end of this spectrum. But doesn’t seem to have been at the extreme where his collecting became hoarding and impeded his everyday life. It was certainly a sacrifice, though: Marès was from an ordinary family and thus funded all of his collecting activities through the money he earned as a professor and artist.

But back to collecting. A psychoanalytic approach (now out of fashion in this area) relates collecting to toilet training. Not sure I understand that. The part I do understand better is that collecting helps establish a better sense of self. Other theories see collecting as the pursuit of a feeling rather than the object itself, linked to consumerism and materialism. Like shopaholics, there’s no doubt that collectors are often not motivated by an object’s material value. They may instead be driven by passion, nostalgia, or a desire to ‘win’ by acquiring objects that are scarce or unique.

Going back to psychoanalysis for a minute, this theory identifies five main reasons for collecting: for selfish purposes; for selfless purposes; as preservation, restoration, history, and a sense of continuity; as financial investment and as a form of addiction. I feel tempted to place Marès into categories three and five. This may be me projecting my own collecting motivations onto another, but from the types of objects Marès collected I feel that preservation, history and continuity were important to him. A sort of ‘if I don’t collect this, what will happen to it’? And the volume and breadth of his collections do point to some level of addiction. An interesting case study for a psychologist somewhere, if the research hasn’t been done already.

Final Thoughts on the Museu Frederic Marès

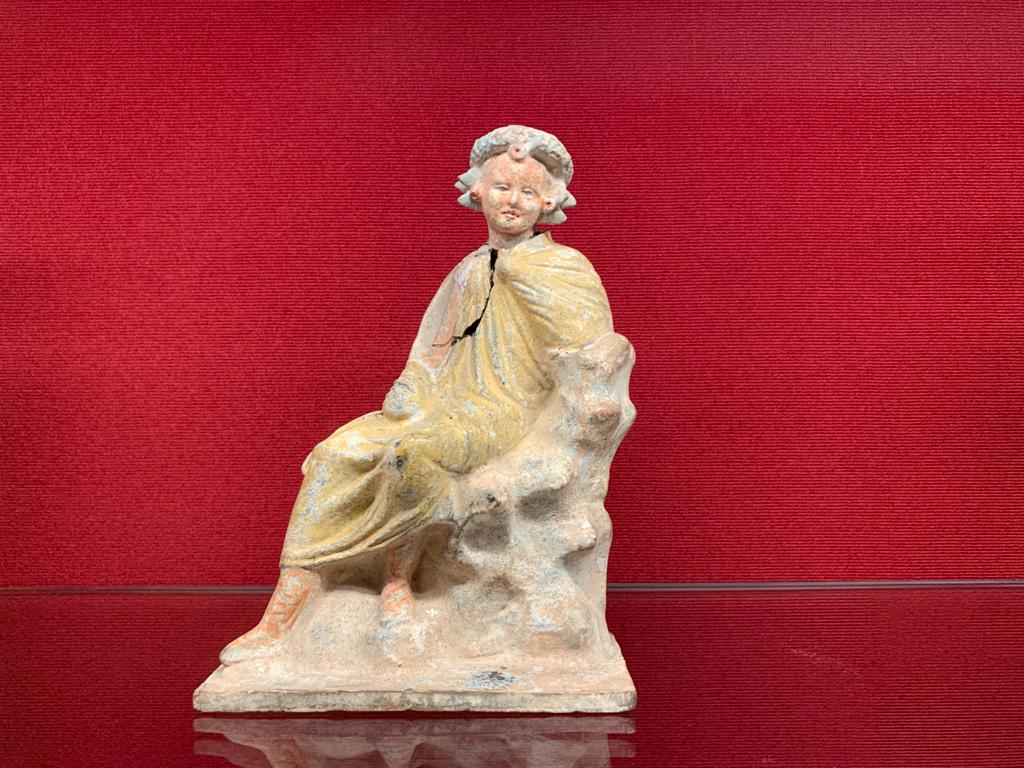

Tellingly, do you know what we haven’t yet talked much about? Marès’s own sculptures. They are part of the collection: see images 2-4 in the section above. A large room is set up as the artist’s library and study. There are numerous examples of his art: studies and preparatory works as well as finished sculptures. The trouble is, they are simply not as interesting as the other things he collected. They’re good, but they’re not great.

And so my theory is borne out: Marès the collector very much overshadows Marès the artist. As we move further from his own lifetime, that will be ever more his legacy. That isn’t necessarily an issue: to be remembered at all is not something most of us will achieve. But I wonder how Marès himself would have wanted it.

Ponderings on mortality aside, to sum up the Museu Frederic Marès: I loved it. This is a centrally-located, well-curated, unique and unforgettable museum. The only thing which would make it better might be a little more information on the objects in its care. It should be top of the Barcelona list for every visitor with an interest in museology and collecting, or a love of the eclectic. I don’t think you’ll regret it.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4/5

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.