Soulscapes – Dulwich Picture Gallery, London

Soulscapes promises “a contemporary retelling of landscape by artists from the African Diaspora.“ What precisely does that mean? Let’s find out!

Soulscapes

One thing I definitely appreciate about the Dulwich Picture Gallery is the variety of their exhibitions. The last time we were there it was for Rubens and Women. The time before that it was art between worlds by Lithuanian M.K. Čiurlionis. And before that, art exploring women and the domestic. They have more than this besides, but in London you can’t quite make it to all exhibitions despite best intentions. The point is that the Dulwich Picture Gallery have more varied and provocative programming than you might think for England’s oldest public art gallery.

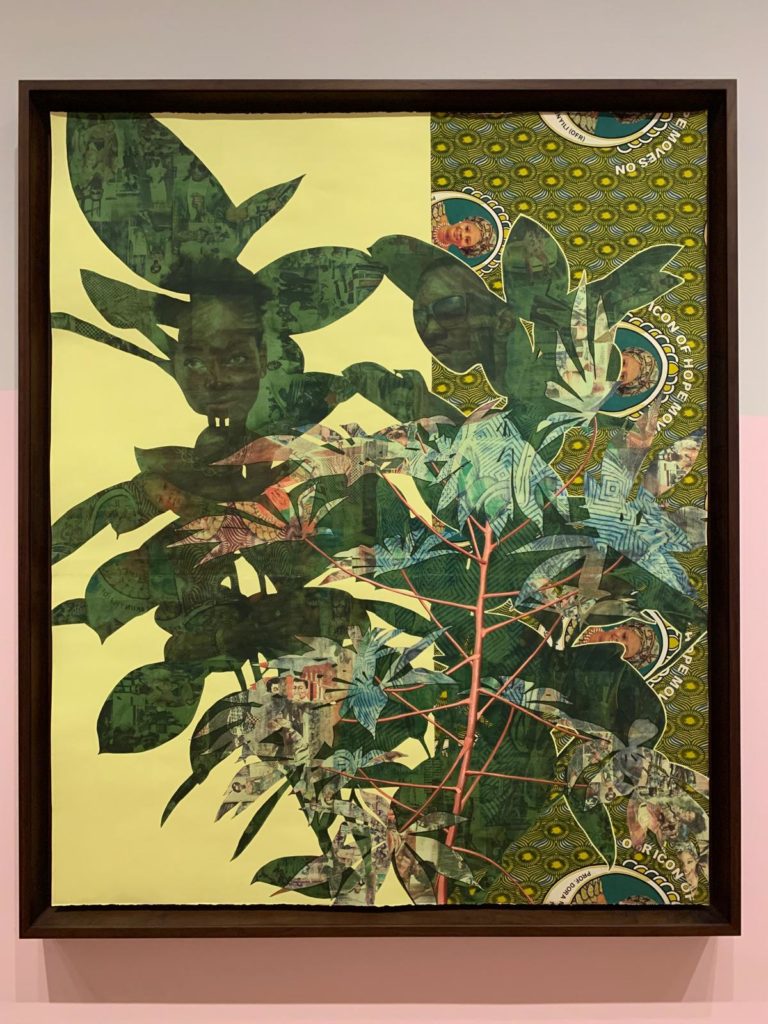

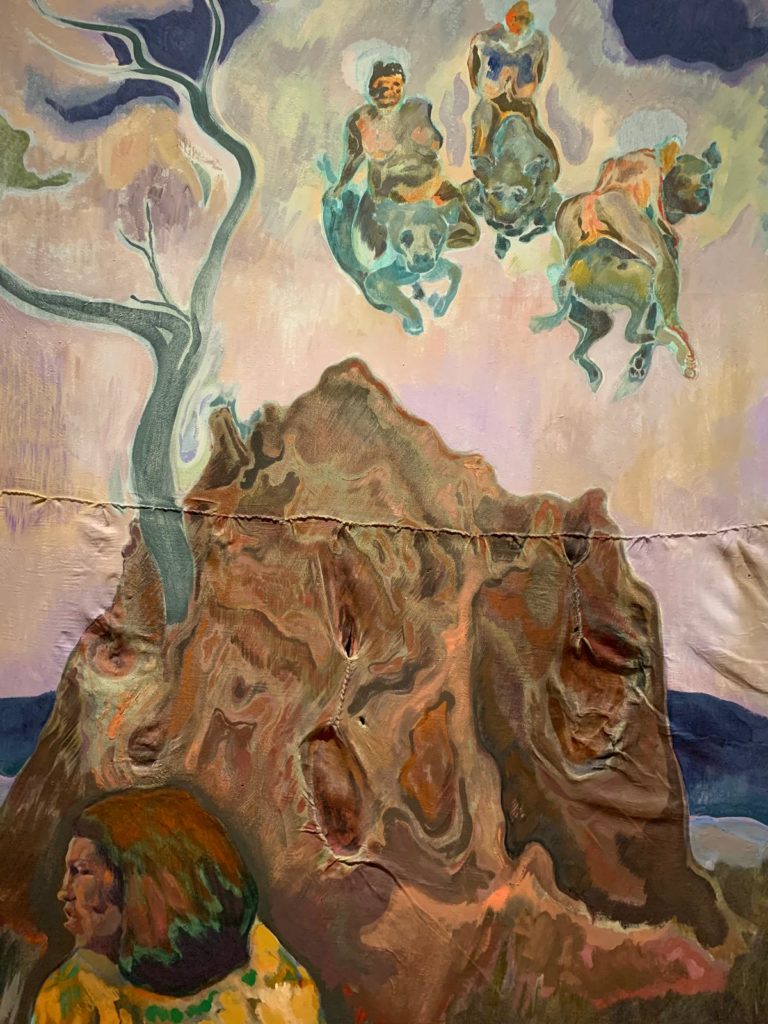

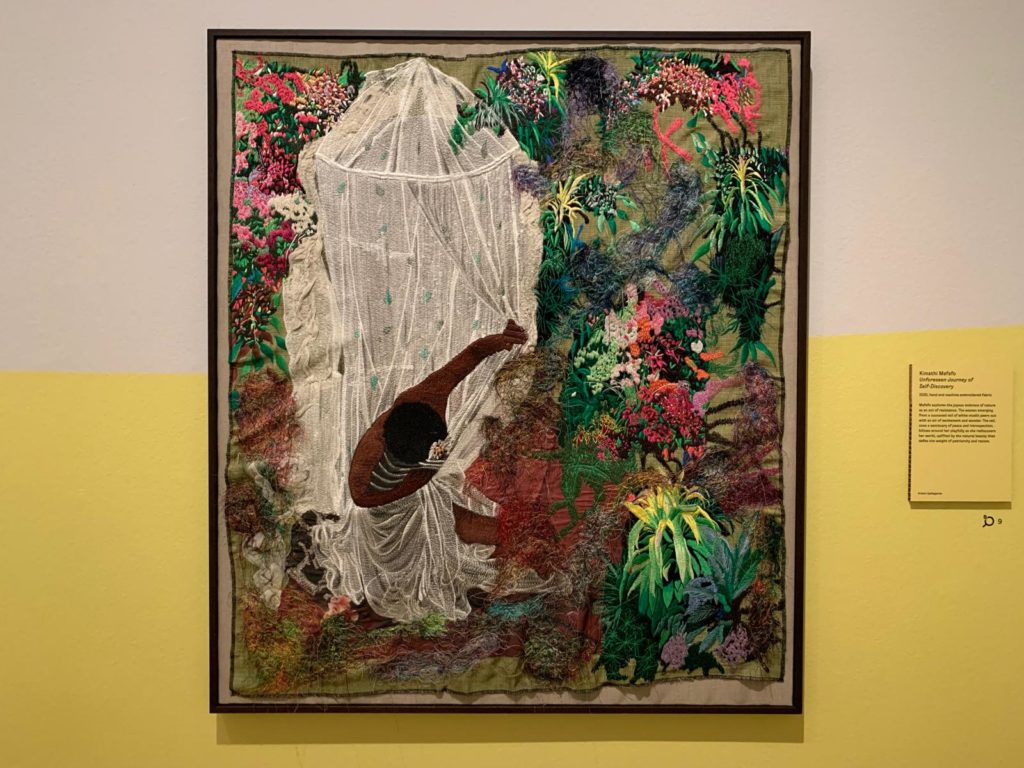

The latest offering at the Dulwich Picture Gallery is Soulscapes. This exhibition showcases contemporary works by artists from the African diaspora which fit the theme of landscape art. The idea apparently came out of the COVID-19 lockdowns, which saw us inhabiting outdoor spaces in a new way. It features very contemporary art (mostly from the last few years), predominantly paintings and painting-esque works in other media. There’s a new commission in the mix, as well as a site-specific installation.

But for a small exhibition space, this exhibition attempts to do a lot. To look at the relationship between people and landscape with a contemporary focus. To select works by artists from the African disapora (those born in African countries or with African heritage via the Caribbean or elsewhere) and unpack the Pandora’s Box that opens. Questions of what landscape means, who ‘owns’ it, how we depict and relate to it. Who belongs in it, and who doesn’t. It’s a lot to ask of circa thirty works, particularly when divided into themes of Belonging, Memory, Joy and Transformation. Let’s see, then, how curator Lisa Anderson (who is also Managing Director of the Black Cultural Archives) gets on.

Belonging, Memory, Joy, Transformation

For a start, selecting such contemporary works is a great way to get current artists onto gallery walls. I noticed that a lot of the works displayed were there courtesy of the artist themselves or their gallery. I would hope that, in time, more would be in institutional or private collections. Such a platform often helps in that endeavour. But enough art market chat. There were also artists I was more familiar with. Michael Armitage, for one, as well as Isaac Julien and Hurvin Anderson.

The downside of the small space is that there is not such a great variety. With the exception of the installation in the gallery’s mausoleum (learn more about that here), most of the art is on a canvas, a screen, or something similar. For a topic that can’t not be political (apologies for the double negative), this plus the fact that landscape art tends to be quite green and soothing means it packed less of a visual punch than I had foreseen. To understand the deeper themes, the artist’s preoccupations and so on, you typically have to read the wall texts. Is that too critical a point to make?

Personally, I was intrigued by the art which played with, upended or interrogated traditional European landscape art. This is probably because the idea of landscape itself: how it emerged and is now taken for granted, is a pet interest of mine. In this vein I enjoyed Harold Offeh’s video work Body Landscape Memory, Symphonic Variations on an African Air. To a backdrop of music by Black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, we see three Black figures relaxed and at ease in typical British landscapes. There’s even a nod to Caspar David Friedrich’s famous painting of man against the elements. Like Jermaine Francis’s photographic work nearby, the very fact that Black people at ease in nature is noteworthy surfaces unspoken barriers, expectations and exclusivities placed on Black bodies.

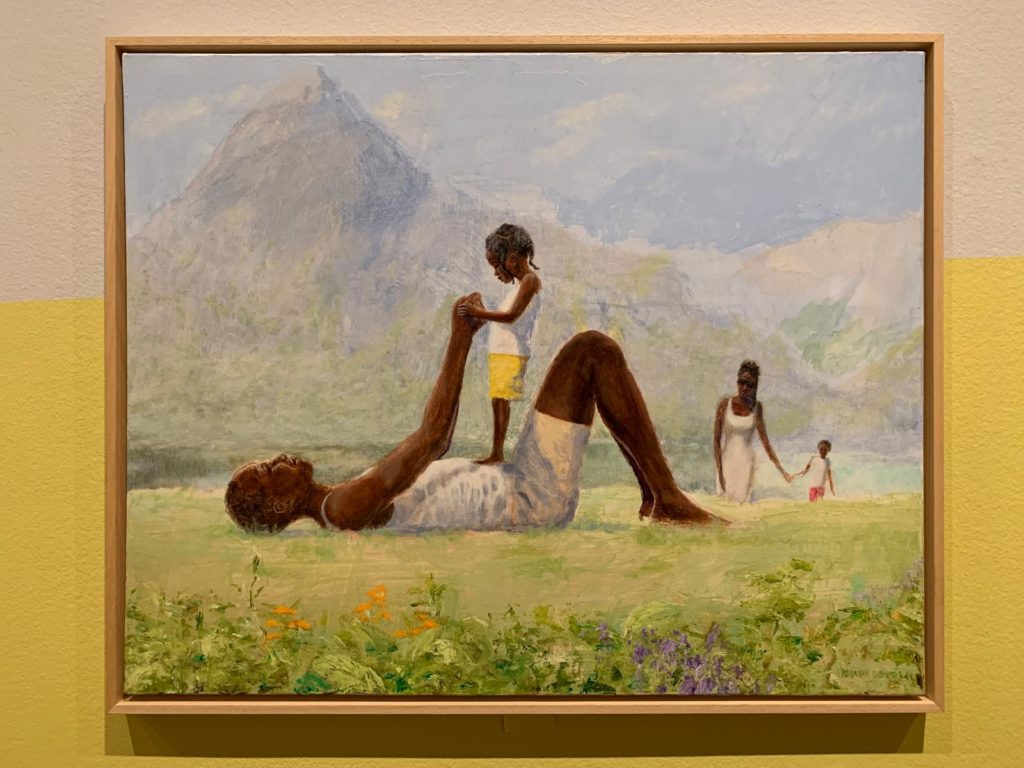

Kimathi Donkor‘s series of paintings continues this dialogue in a later room, consciously choosing to show scenes of Black joy in traditional landscape settings. Aesthetically the latter weren’t my jam, but I appreciate the threads woven between different artists even when not grouped together.

Landscape Art and the African Diaspora

Come to think of it, when I think of land art (which is not so frequently), I’m thinking primarily of White Americans or maybe Brits, 1960s-1980s, that kind of thing. Richard Long, etc. This is not that, if you discount documentation of a large-scale work by EVEWRIGHT. Or, if I’m thinking of landscapes, I probably am thinking about Constable, Gainsborough – well-established figures in the art canon. So what I did appreciate in Soulscapes was its reminder that the whole world is made of landscapes, and everyone has a response to them. Selecting the lens of artists from the African diaspora merely reveals to us a different set of landscapes, or the same landscapes viewed in a different way.

I think, really, I just wanted the exhibition to be bigger. I think bigger might have meant bolder, if there was room for some chunkier art not mounted to walls. And my ideal version of this exhibition would have found a way to bring into the discussion the very traditional landscape art by the very famous artists which hangs on the walls beyond the exhibition space. But no matter: I learned about new artists, broadened my horizons and admired lush and beautiful landscapes, so not a bad museum outing all things told.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Soulscapes on until 2 June 2024. More info here.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.