ZSL London Zoo

The Salterton Arts Review visits ZSL London Zoo to discover the intertwined histories of zoos and museums. And to see the animals, of course!

A Visit To ZSL London Zoo

It’s happened a few times on this blog that I’ve written about different types of institutions (zoos, aquariums, botanical gardens) and felt the need to justify it. Writing about museums and exhibitions in a contextualised, museological fashion? No problem, that’s basically my bread and butter. Or my jam, to continue the breakfast metaphors. Taking that approach outdoors to go on a heritage walk around a city or neighbourhood also makes sense to me. It’s just when it’s one of those institutions with live exhibits that I fall back into explanations.

So after a visit to ZSL London Zoo, I decided to do something about it. And by doing something, I mean reading. There isn’t a whole lot of writing looking at the overlap between zoos and museums. But there is some. And what there is is both interesting, and gave me more clarity on my thinking in this area. So let me now share it with you: what better backdrop than one of the world’s most established and well known zoos?

To go right back in history, one of the first similarities between zoos and museums is their origin story. By which I mean it’s possible to make the argument that both zoos and museums emerged first in Antiquity. But also more plausible that they emerged properly in the 18th Century. One article I read (Mason, 1999 – yes I’m citing this time!) names Queen Hatshepsut’s menagerie in the 15th Century BCE as the first zoo. She had monkeys, leopards, birds and giraffes. Another author (van Mensch, 2011) notes that the Alexandrian Mouseion was both a museum and a zoo (and a library and a university) and so was a forerunner of both.

A History Of Zoos Continued

So arguably there are ancient examples of both museums and zoos. But zoos as we know them today emerged at basically the same time as museums. In the case of zoos, there were a couple of trendsetters in the 18th Century (Paris and Vienna), followed by more in the 19th, including what is today ZSL London Zoo.

Why did these institutions develop at the same time? Well, as I’ve written about previously, both are a product of the Enlightenment. Colonialism is also tightly connected to the Enlightenment, but is not our subject of discussion today. This period in intellectual circles was about understanding the world: coming up with systems of taxonomy and classifying everything into them. The earliest museums did this in a less scientific way (cabinets of curiosity bringing together natural history and art objects), just as the earliest zoos did (menageries of ‘exotic’ animals). But as both evolved, they became more about knowledge. Zoos are a place for a collection of named animals to be kept and studied. They are a type of museum, where the objects happen to be living ones.

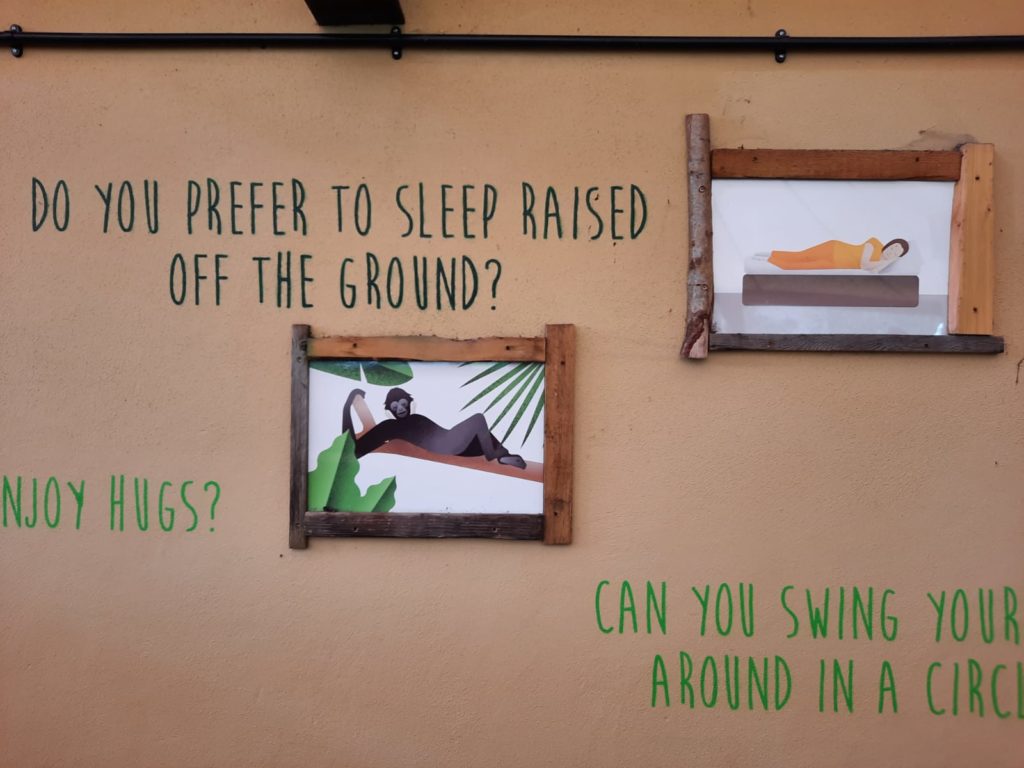

But is that still what zoos are about? Since their inception, their form and purpose has perhaps shifted more than that of museums. Early visitors to zoos frequently encountered captured wild animals. Today this is less palatable. Instead, zoos are more about education and species preservation than visitor pleasure and study. The shift from wild to bred animals is partly behind this change: animals born in captivity cannot be studied in the same way as animals in the wild. But it’s also about our changing relationship to the natural world, both our place in it and our responsibility to care for it.

What Light Does ZSL London Zoo Shed On The History Of Zoos?

If we take ZSL London Zoo as an example, we can see many of these historic trends play out. ZSL London Zoo (the ZSL stands for Zoological Society of London) claims to be the world’s oldest scientific zoo. It opened in April 1828 as a place for scientific study. The move away from menageries towards more scientific approaches to animal collections is exemplified by the fact that the animals historically displayed at the Tower of London were transferred here in 1831.

London Zoo, on the same Regent’s Park site it inhabits today, opened to the public in 1847 to help with funding. It’s had many ‘firsts’ over the years: first reptile house, public aquarium, insect house and children’s zoo. Changing from a reference collection to a place of public entertainment is a big change, and what the public expect from this entertainment has also changed over the years. Close inspection of the animals and activities like chimpanzee tea parties were once common. Today ZSL London Zoo is one of many to prefer park-style enclosures where animals can still be sighted but lead a more comfortable existence. This idea isn’t as new as you might think: the first example was in Hamburg in 1900.

The 20th Century was also an interesting time for ZSL London Zoo. In 1931 ZSL opened Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire. The world’s first open zoological park, Whipsnade was a trendsetter, allowing a different way to care for and observe animals. During WWII many animals (the most valuable specimens) were sent here. Back at Regent’s Park no animals died as a result of bombing, but the venomous animals were sadly put down as a preventative measure in case of escape. In the 1960s ZSL London Zoo was involved in the first ever cooperative breeding programme: of Arabian oryx, with Phoenix Zoo in Arizona.

In the 1990s things almost came to an end. The zoo had been running at a loss for years, and government funding was withdrawn. ZSL London Zoo only made it through with a ruthless refocusing and cost cutting exercise, and donations to help bridge the shortfall. Luckily they did make it through, though, enabling us to visit today!

Visiting ZSL London Zoo

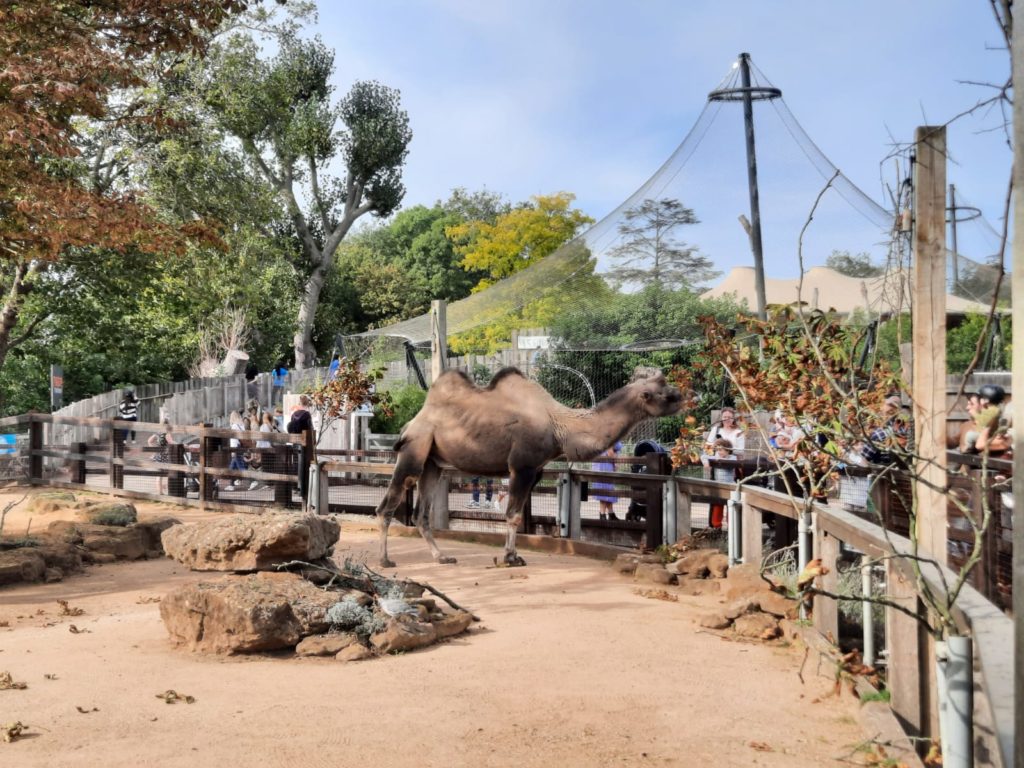

London Zoo, as an urban zoo within Regent’s Park, is by no means the largest zoo I’ve been to. But it still needs a good half day to visit all the attractions. The zoo is organised into coloured zones, and within each zone are groupings of animals. In the Blue Zone, for instance, you can find gibbons, camels, tigers, birds, reptiles and assorted other animals. Where different animals found together in the wild can peacefully coexist, they do (like in the Outback or Into Africa exhibits).

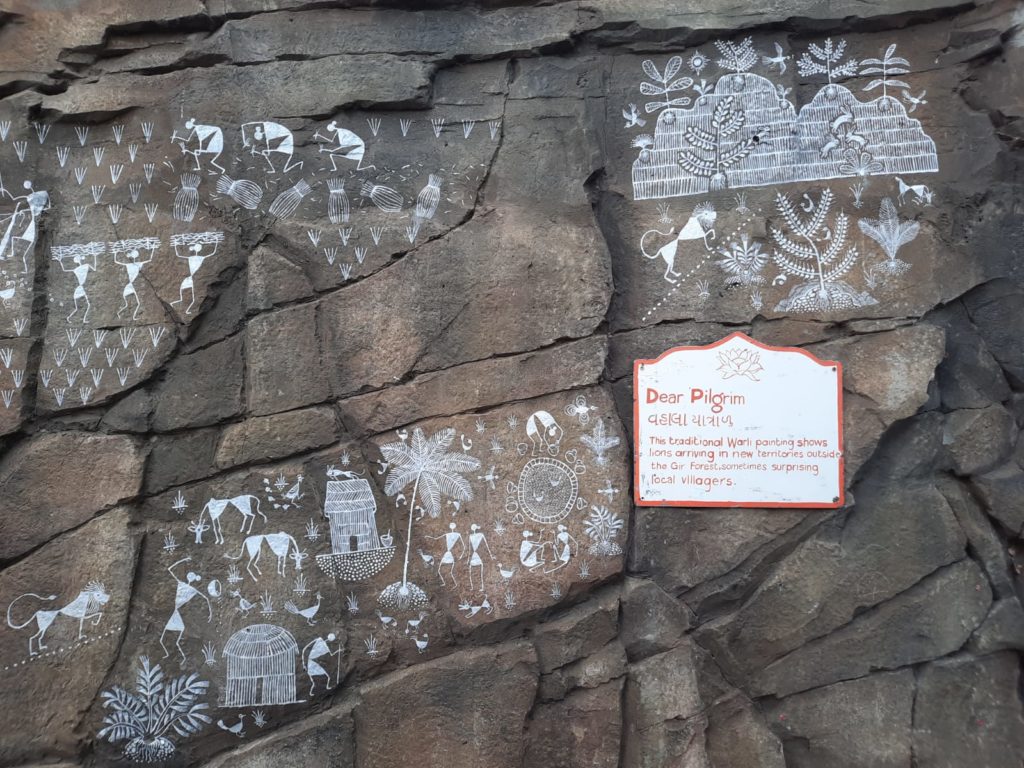

There is plentiful information available during your visit. You can read about the animals, their habitats, their conservation status, and their habits. There were a couple of interesting instances where ZSL London Zoo attempt to create a more immersive environment and bring in some heritage or broader cultural elements, too. I’m thinking in particular of Land of the Lions (which also has monkeys), which recreates the feel of an Indian village with a pilgrimage route for visitors. So there are opportunities to learn about more than just the animals.

There are also plenty of entertainment options available. Some of the enclosures are open, in the sense of allowing you to share space with the animals. You can’t touch them, of course, but there’s still a thrill to crossing paths with lemurs, sloths, birds and monkeys. There’s also a petting zoo for the young or young at heart. For those who want to spend more on their zoo experience there are a range of paid activities, from animal feeding all the way up to overnight stays.

Do come prepared. You can bring your own food, which saves having to go to one of the busy restaurants. It’s also a good idea to plan out your route. You will cover a lot of ground if you try to see everything, so make sure you’re not doubling back as well. And don’t forget to prepare for the elements: even if you’re just going between indoor enclosures you will be outside a lot.

Education Or Entertainment?

I think one reason that I’ve had for justifying my inclusion of ‘living museums’ (if we can call them that) in the past is that the line between education and entertainment seems more blurred than in a classic museum. In a museum setting, I am going to look at and learn about objects. In a zoo (or aquarium), I could easily avoid information panels all day and just have fun looking at the animals. We know that zoos have a conservation agenda. The days of the animals being there purely for entertainment are gone. We should come away from a trip to the zoo with a better understanding of the impact of human activities on different habitats, and how we could influence that with behavioural changes. But do we?

I’m not the only one to wonder this. Research, albeit limited, has focused on the same topic: the measurable impact of zoos on conservation and sustainability (Fraser & Sickler, 2009). It’s not black and white. ZSL describe themselves as “an international conservation charity driven by science, working to restore wildlife in the UK and around the world by protecting critical species, restoring ecosystems, helping people and wildlife live together and inspiring support for nature.” Not all of these require visitor engagement – I guess our duty is the fairly vague ‘support for nature’?

But then again young people could go to Young V&A and take advantage of the play facilities, not overtly learning anything to do with the museum’s mission or about its collections. So perhaps it’s the difference in setting and the living nature of the ‘objects’ in a museum setting which make this trickier to parse out.

Final Thoughts

Firstly, could we please take a moment to appreciate the image directly above, with the attempted escapee?

Ok, back to the topic at hand. I enjoyed doing this exercise of looking further into the history of museums and zoos in order to clarify my thinking about them. It confirmed what I had felt all along. That zoos (and aquariums) are museological enough to get the Salterton Arts Review treatment. They may have outwardly different focuses today, but that merely masks shared origins in the Enlightenment. Or Antiquity if you want to go back to the Mouseion.

One thing I haven’t spoken about are the animals I saw, and which ones were my favourites. I liked the monkeys, the tigers, all the greatest hits. But my favourite animals at ZSL London Zoo are the naked mole rats. I was disappointed last time I visited when I thought they had removed them from display. But I think perhaps they had just moved into the Night Life enclosure, which is where they can be found today. I love those ugly little guys, and really enjoy watching their hive-like behaviour. So there you have it: naked mole rats.

This hasn’t been my typical sort of post, but hopefully you learned more about zoos in general, and ZSL London Zoo in particular. Maybe on your next visit you will spot some of the changes that have been made over time in how the living collections are ‘stored’ and viewed. And now, please read on for a quick bonus section on architecture!

Bonus Section: Architecture At ZSL London Zoo

There’s just time for a quick look at ZSL London Zoo’s architecture before we finish. This is a very interesting topic, because it demonstrates different zoological as well as architectural trends. A lot of the earliest animal enclosures no longer exist, because they were so far from fitting contemporary needs. But you can see a few remaining ones like the Reptile House, or Blackburn Pavillion which now hosts a bird exhibit.

ZSL must also contend with at least one structure which is so architecturally important they must conserve it, while not being able to use it for its intended purpose. I’m talking here about the 1934 Penguin Pool by Georgian-born Berthold Lubetkin. Architecturally it was a revolutionary use of concrete, creating a sleek, modern design. But while it was a step forward in animal welfare, it still very much put the emphasis on visitor entertainment. The current, more natural, Penguin Beach opened in 2011.

There are many more buildings and structures of interest to see on a day at ZSL London Zoo. The Giraffe House, for instance, is the only Victorian animal enclosure remaining, dating to 1837. The red river hogs live in the Brutalist 1960s Casson Pavilion. The idea is that it resembles elephants gathering around a watering hole. Or there’s the Snowdon Aviary. Since 1965 it has sat beside the Regent’s Canal, one of the sections of the zoo that you can see into from outside. It was another revolution for ZSL London Zoo when it opened, being the first walk-through aviary. Designed to give as much space as possible to its inhabitants, in 2022 it became Monkey Valley, swapping avian for primate residents.

So there we have it. Hopefully a little incentive to look not just at the animals but at their homes on your next zoo visit.

List of References

- Fraser, J., & Sickler, J. (2009). Measuring the cultural impact of zoos and aquariums. International Zoo Yearbook, 43(1), 103–112.

- Mason, P. (1999). Zoos as heritage tourism attractions: A neglected area of research? International Journal of Heritage Studies, 5(3-4), 193–202.

- Van Mensch, P. (2011). The musealisation of Knut. Dilemmas in the relationship between zoos and museums. COMCOL Newsletter no. 13 (April 2011), 4-7.

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

Such a fraught topic; many people find the idea of animals in captivity for entertainment distasteful and, as you said, unnecessary if species preservation is the aim. And it’s hard to compete with TV for close-up insight into animal behaviour. It feels like zoos will become extinct (or evolve) and be replaced with something suitable to contemporary taste.

I agree, at the moment it’s a little like we have retrofitted contemporary concerns for animal welfare onto a framework that doesn’t quite fit.