Noah Davis – Barbican, London

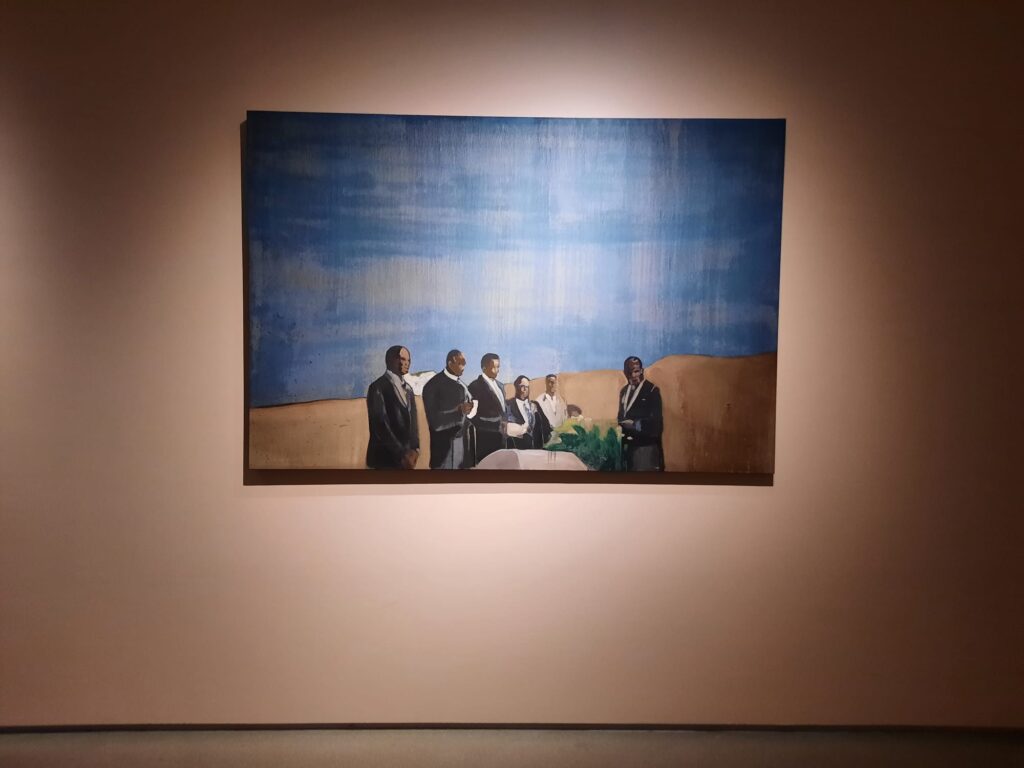

The Barbican’s latest monographic exhibition is a wonderful tribute to Noah Davis, a talented and thought-provoking artist who kept pushing his creative boundaries.

Noah Davis: an Introduction

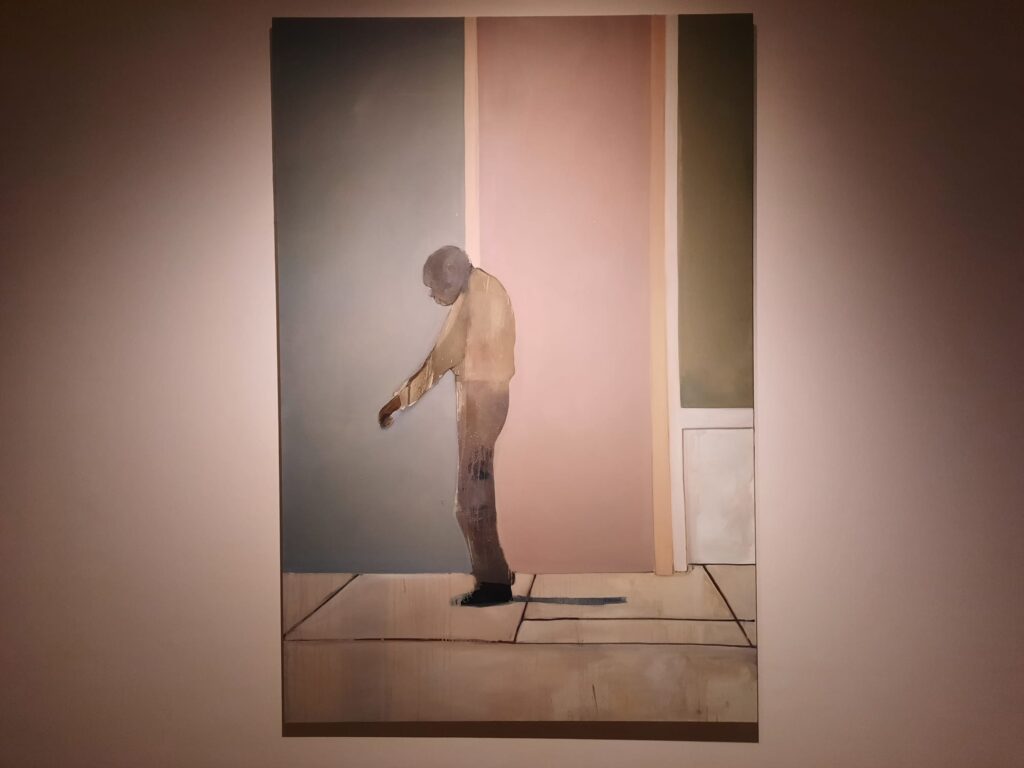

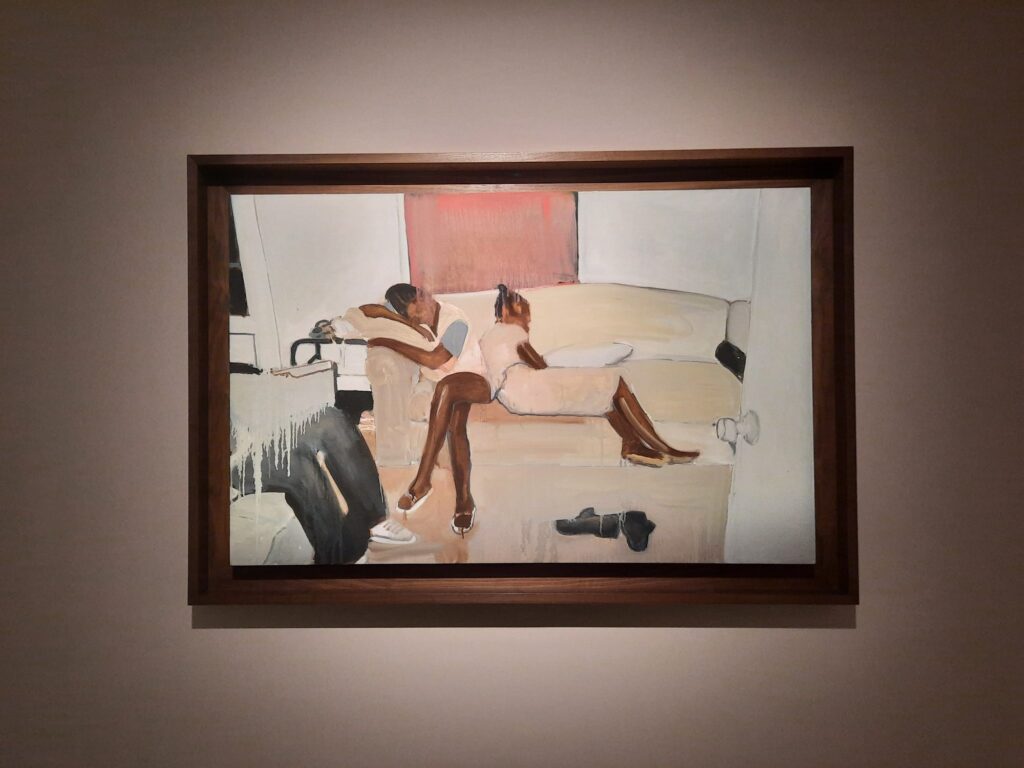

The striking thing as I look around the familiar Barbican gallery space is how varied the works are. I mean, a lot of the exhibitions they stage here are thematic and mixed media, and this one is monographic and almost all paintings, but still. Noah Davis is immediately interesting as an artist who did not allow himself to be defined by a single style.

Why didn’t I know his work, then? It ticks a lot of boxes for me: visually compelling, contemporary painting which is politically engaged. Maybe I wasn’t familiar with Davis because he was part of the West Coast art scene, whereas I have a bit more familiarity with New York. Or it could be because his career was cut short by his death in 2015. He was only 32.

Taking a step or two back to start at the start, Noah Davis was born in 1983 in Seattle. His parents were Keven, a sports and entertainment lawyer who represented the Williams sisters among others, and artist, non profit leader and writer Faith Childs-Davis. Some artistic leanings were already in the blood, then, and Noah showed an interest in pursuing art from a young age. In fact, by 17 he was set up with a studio: it seems his parents found that preferable to the mess of Noah painting at home. His brother Kahlil Joseph is also an artist.

Davis went on to study at the Cooper Union School of Art in New York, but did not graduate. In 2004 he moved to Los Angeles, and started exhibiting paintings in 2007. A job during these early years at an art bookstore helped him to develop wide ranging knowledge and source material.

Early Artistic Confidence

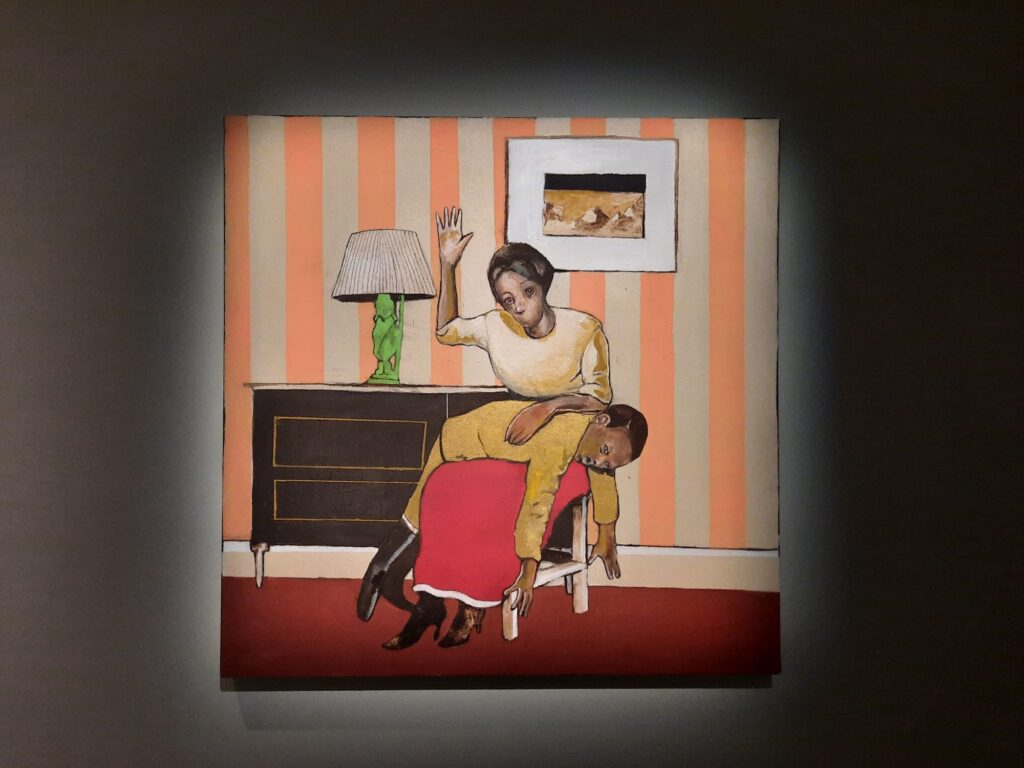

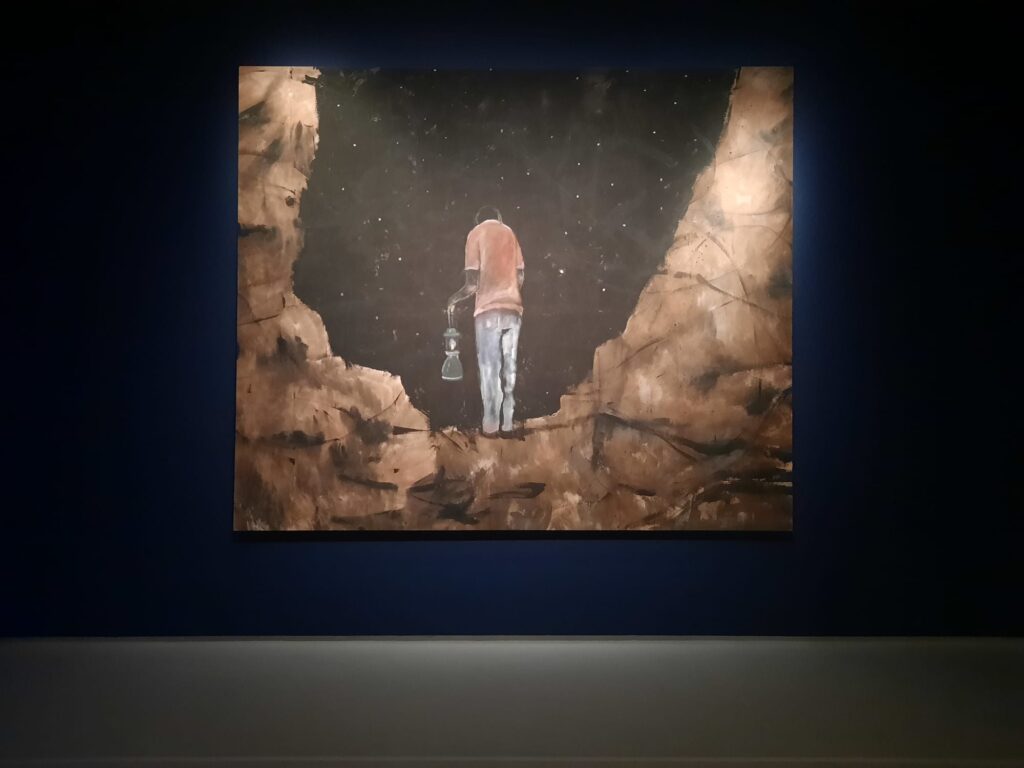

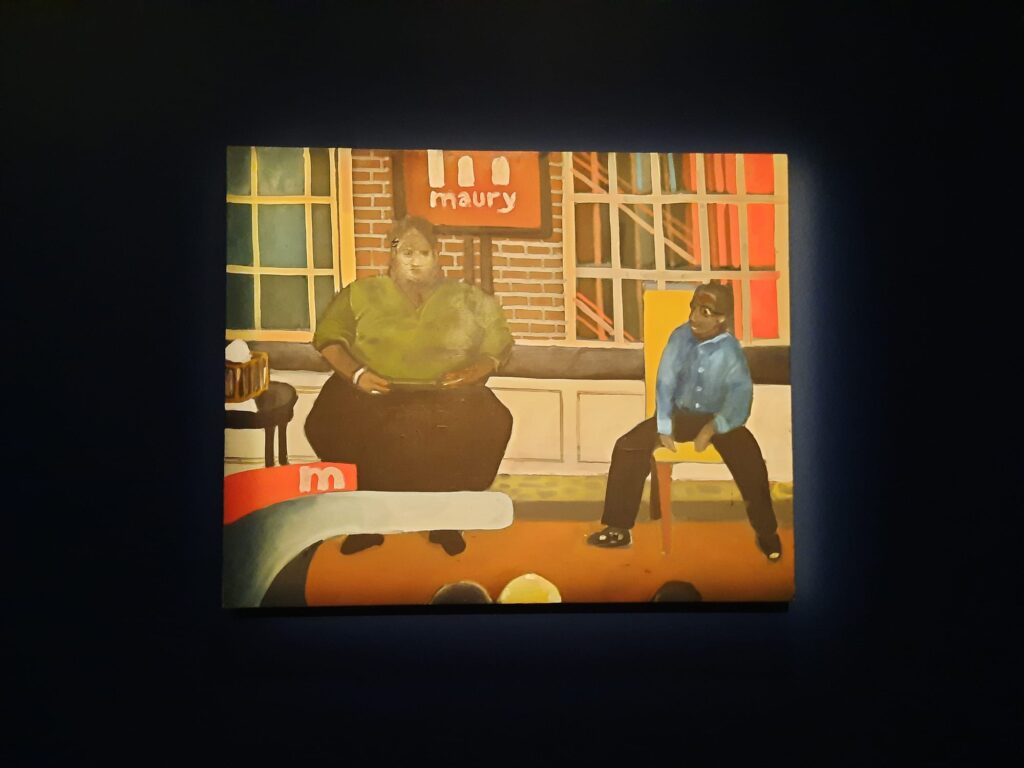

The Barbican exhibition is chronological, and we get a definite sense of Davis as an artist who came onto the scene brimming not just with talent, but with ideas. He predominantly painted Black figures, but also experimented with more abstracted works, and with sources like photos and TV stills as well as his own imagination.

Davis, it seems, also held himself to a high standard. After some initial success, he was keen not to be pigeonholed into performatively painting Black life as imagined through a White gaze. He wanted to paint communities and families, not the pain and suffering of the mainstream news cycle, or hip hop, or whatever else the art market expected of him. And so for his next series he went in an entirely different direction.

As part of his solo show Nobody in 2008 he painted three almost abstract canvases. The shapes were actually those of key swing states in the US, and the purple paint a blend of the red and blue of the Republicans and Democrats. Areas of dense population were highlighted out in glitter. A bold departure. But the works didn’t sell. A friend later purchased one and thus ensured its survival. Davis reused the other two canvases for later works. The Barbican represents these missing paintings from Davis’s catalogue with squares of light. Very clever. And very interesting to see how Davis experimented and tested the limits of his visual language.

Community and the Underground Museum

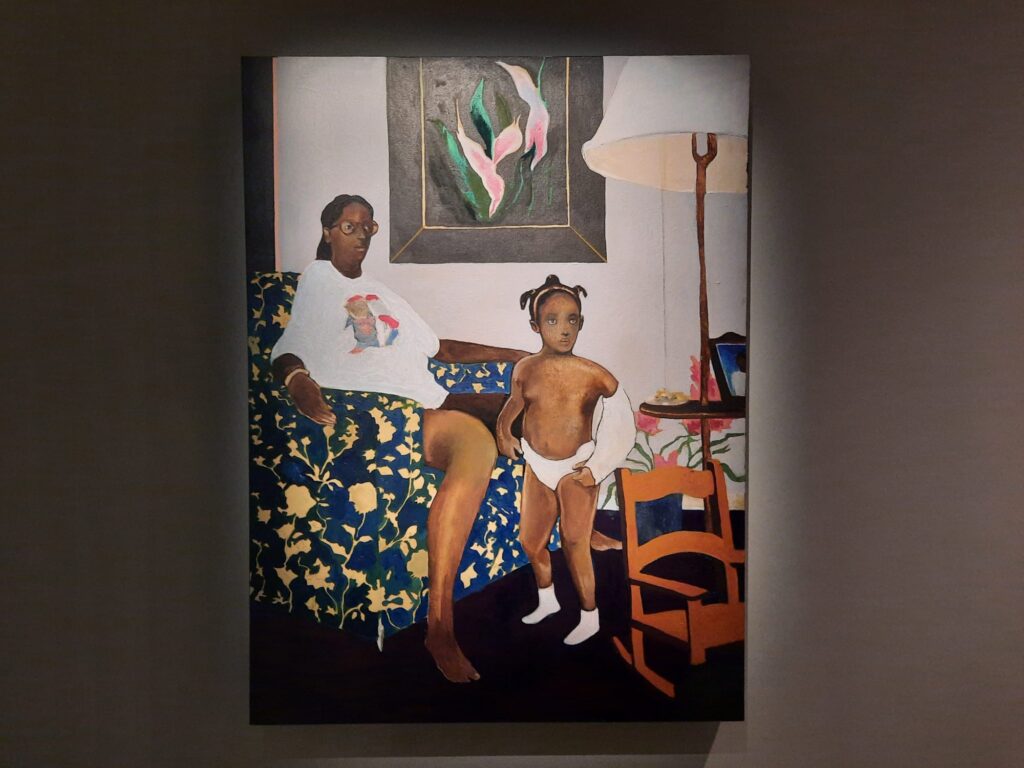

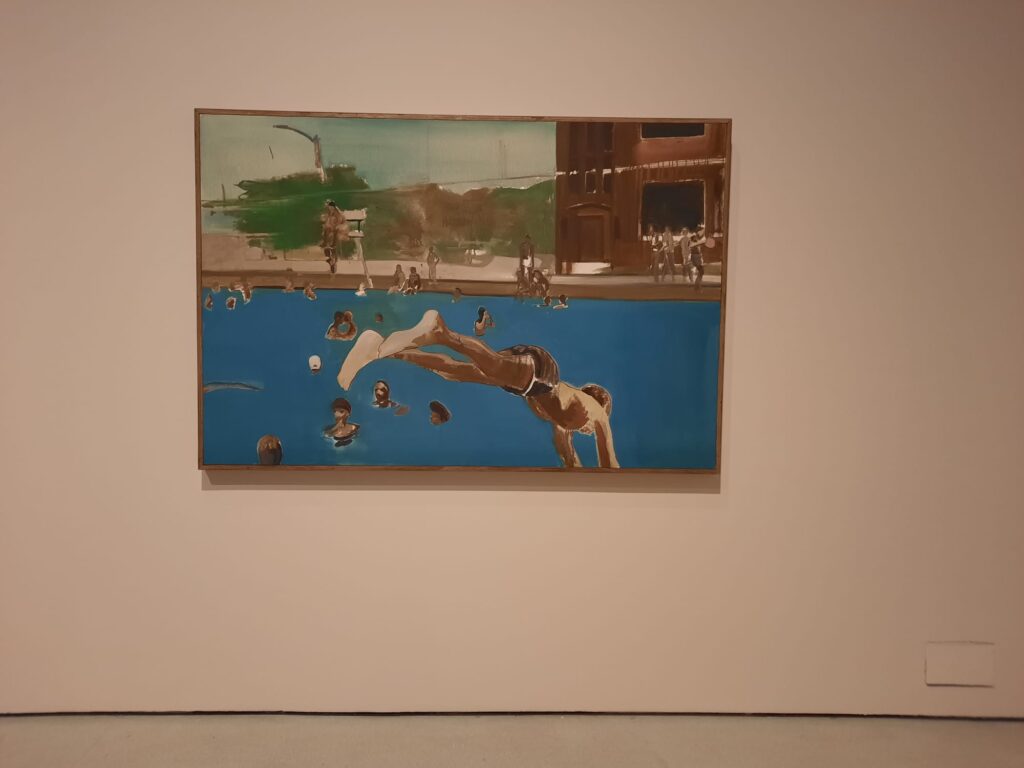

From here Davis’s work returned primarily to paintings of Black figures. He continued to draw on a range of sources. Within this exhibition we see Black people on the street, at the pool, at home. Most are firmly situated in the US. But there’s also part of a series painted from images of the Congo. A bit more on geography and Davis’s underlying critiques in a bit.

But community was clearly something important to Davis. When he received an inheritance from his father in 2011 with an instruction to “foster community and joy”, he and Karon rented four shop fronts in Arlington Heights, Los Angeles, to open the Underground Museum in 2012. Their idea was to bring art and culture to a neighbourhood which historically hadn’t benefited from this kind of investment. And again Davis showed great creativity and ambition. He reached out to established institutions to discuss loans for exhibitions. Most declined, some responded positively. So he also made his own works. One of the rooms at the Barbican is filled with (mostly) reconstructed homages to Jeff Koons, Marcel Duchamp or Dan Flavin. In other words, if turning household items into sculptures is good enough for those well-established figures in the art historical canon, why not for Davis and his new museum?

I was sad to see the Underground Museum closed its doors in 2022. But not surprised. Covid was hard for so many cultural institutions, let alone one still establishing itself outside of the mainstream. And the statement when it closed also referenced the difficulty of allowing new directors to step in and run the museum, and needing to take the time to properly grieve Davis’s death. He was diagnosed in December 2013, exactly two years after his father’s death from cancer, with liposarcoma. A rare cancer affecting fat cells, the treatment was harsh but Davis continued to work and enjoy family life until his death in 2015. There are a lot of “what ifs” in the exhibition when it comes to the continuation of Davis’s art, and the Underground Museum project.

Drawing on Deep Knowledge of (Art) History

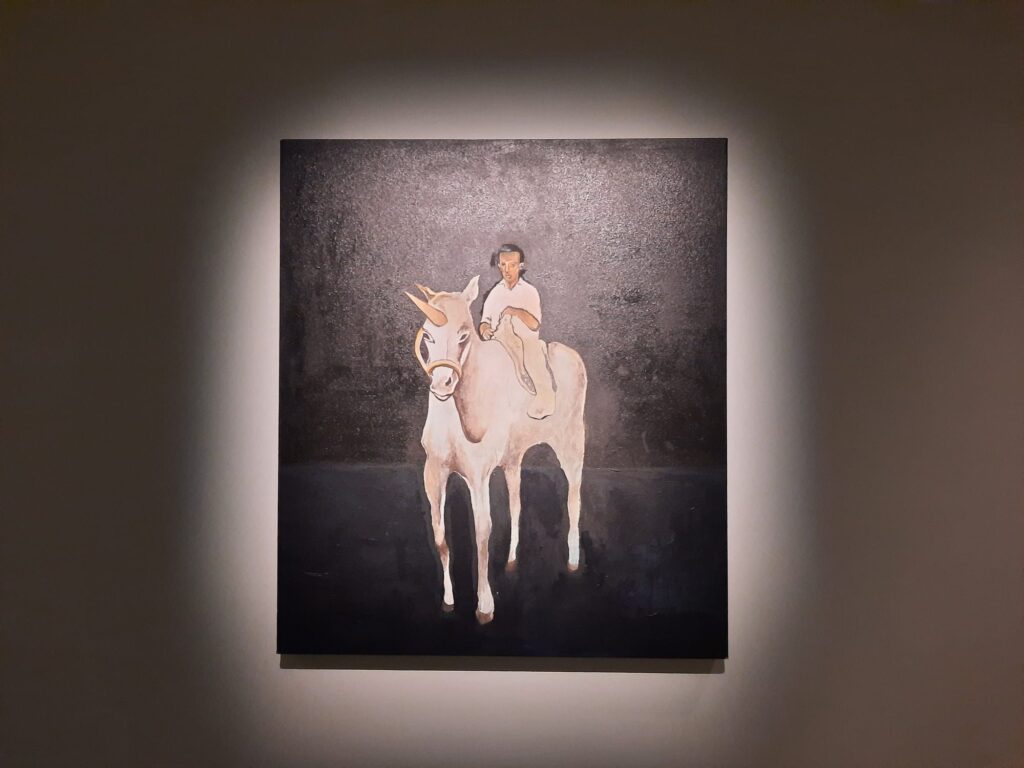

One element of the Noah Davis exhibition I particularly enjoyed was the way the artist drew on history and art history. As I mentioned before, as well as his artistic education, an early job in an art book shop honed Davis’s eye. Many of these sources and inspirations come through in his work. He also incorporated a lot of history. One early work, 2007’s 40 Acres and a Unicorn, references broken promises during the American Civil War. It was by coincidence that I visited the exhibition shortly after Kendrick Lamar’s Superbowl show once again reminded us of this incident. Memory is short, I guess, when it’s in the interests of maintaining the status quo.

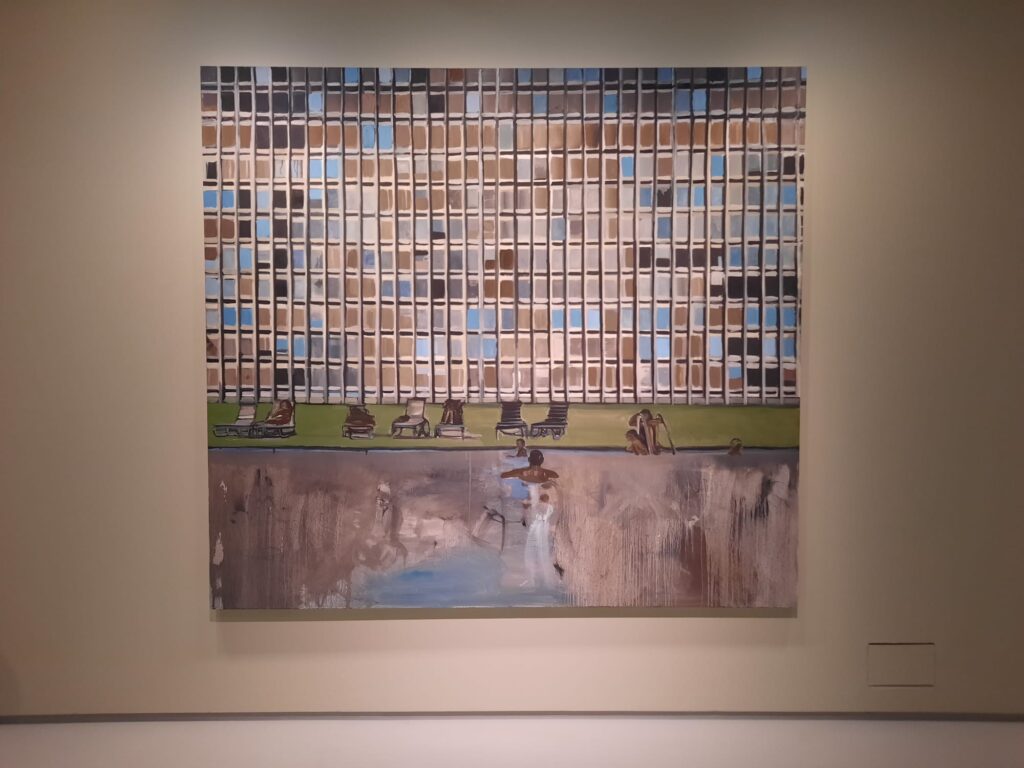

It’s just one way in which Davis addressed historic and current racial injustices for Black people. Another is interesting because it coopts architecture to this end. In a few different series, Davis referenced the architect Paul Revere Williams. Born in 1894 and working in LA, Williams designed celebrity homes as well as public housing, civic and commercial buildings. He had to learn to draw upside down as prejudice precluded him from sitting next to White clients. One of Davis’s series reimagined a 1941 housing project by Williams, Pueblo del Rio. Williams designed it as a garden city, but it later became “one of the most impoverished and dangerous areas in the city”. Davis’s paintings suffuse it with lightness and beauty once more. Ballerinas dance, a mother and child cross the street, musicians play their instruments.

What these and other works and series achieve is to put the focus, not on Black suffering, but on the societal constructs which continue to reinforce inequality. Much like the work of someone like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, they also create a space where Black people can be themselves. The subjects are not mediated by the White gaze in these paintings. There is something very freeing in that. If I did have a fleeting thought about then coming to the exhibition and applying my White gaze to the paintings, that’s probably a thought for another day.

Final Thoughts on Noah Davis

The Barbican exhibition space is a big one. I’m often very ready to pop down to the café by the time I reach the end. But on this occasion I couldn’t help but to want more. It’s not just the inevitable feeling of sadness and injustice knowing in advance that a life was cut short. It’s that Noah Davis was a talented artist with a lot of insight and a unique perspective. He would have had something important to say about the moment we’re currently through. What a shame we missed out on that.

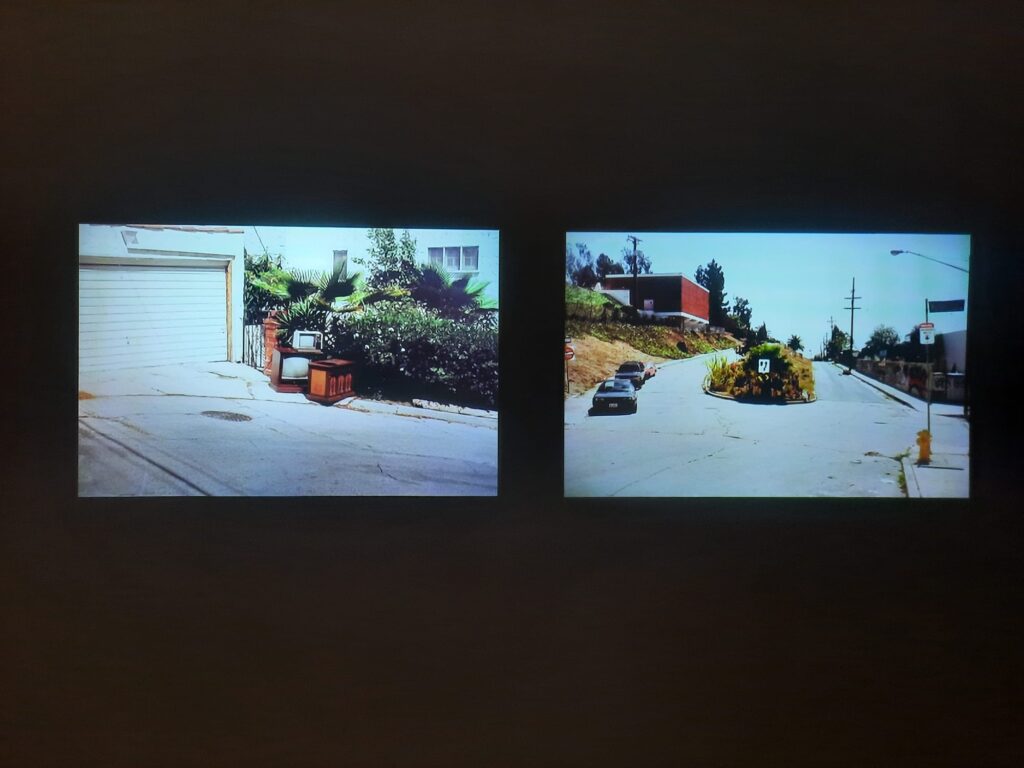

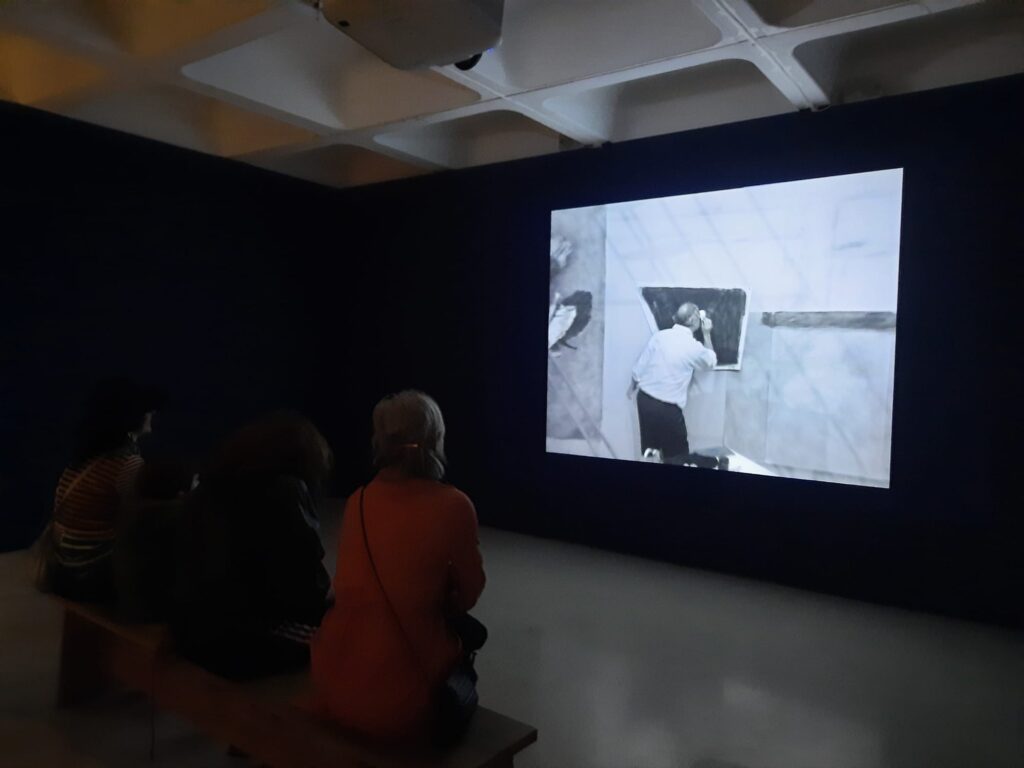

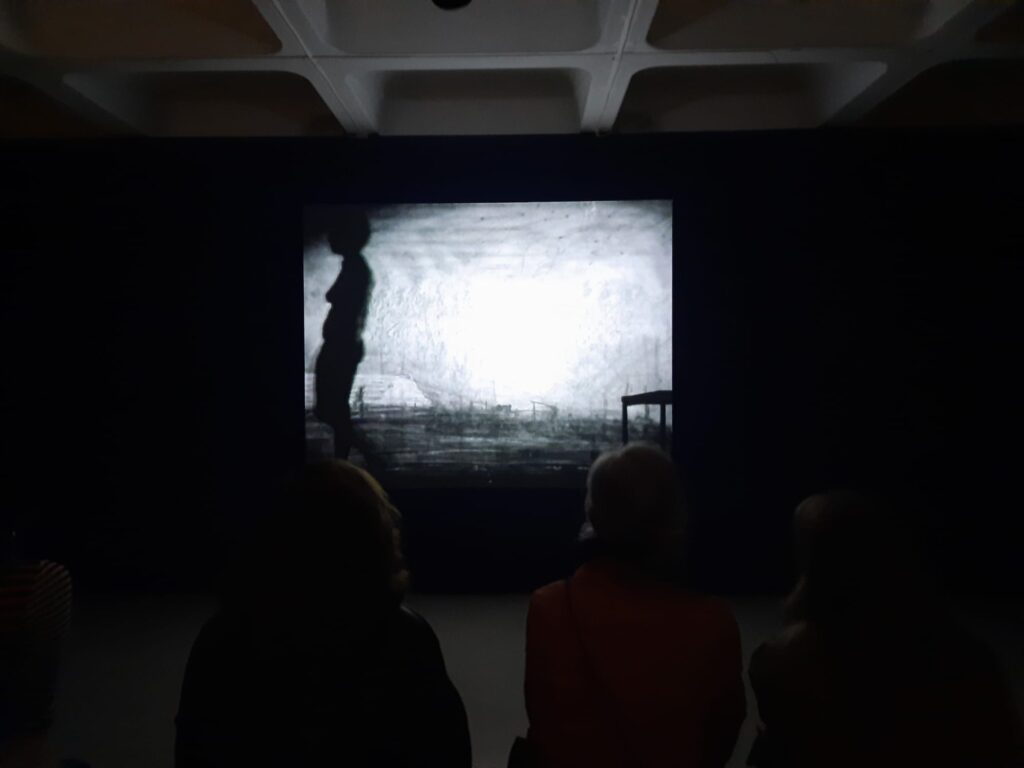

What a joy to have this exhibition, though. It’s so well curated (by Wells Fray-Smith and Eleanor Nairne). The chronological hang tells Davis’s story beautifully and introduces themes and ideas for further reflection. There’s also just the right amount of art in other media to relieve what would otherwise be a show of paintings. I mentioned the sculptures already. There are also found photos which Davis mined as source material. And a beautiful film by William Kentridge. When Davis was looking for institutional collaborations for the Underground Museum, Helen Molesworth, chief curator at MOCA in LA, responded positively. Davis curated many possible exhibitions from MOCA’s list of holdings. But a presentation of Kentridge’s 2003 Journey to the Moon was the only one he lived to see. Along with some meditative paintings from Davis’s final months, it’s a beautiful end to an inspiring exhibition.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 5/5

Noah Davis on until 11 May 2025

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.

wow – he did some really good paintings – such a pleasure to see amid a see of plastic contemporary art. The compositions and colours are really strong and the content is engaging. Truly an artist.