Edward Burra – Tate Britain, London

Edward Burra’s vivid, unsettling vision is given rare breathing room in this well-curated and thoughtful exhibition.

Two-for-One Exhibitions: The Perfect Solution

It’s no secret I often find Tate Britain’s exhibition galleries overwhelming. In fact I complain about it so frequently, even I’m sick of it! The winding trek through its ground floor temporary exhibition space can feel like a gauntlet: long, lofty, and increasingly exhausting. The scale, the density, and the sense of persevering until you reach a final gallery you can no longer appreciate, tend to wear me down. So it’s a welcome surprise to find the space split cleanly in two for the new pairing: Edward Burra and Ithell Colquhoun, the latter transferred from Tate St Ives. Each show has its own entrance, but both are covered by one ticket. Crucially, they each feel purposeful and self-contained.

This simple spatial intervention improves everything. You can take a break between exhibitions, clear your head, and enter each artist’s world on its own terms. It’s still a lot of ground to cover (over 100 pieces between the two exhibitions) but you’re not compelled to take it all in at once. The pacing feels reasonable.

And there are benefits besides being visitor-friendly. The bifurcated layout also does curatorial justice. Colquhoun’s mystic symbolism and Burra’s hallucinatory social realism don’t have to compete. Each show has its own rhythm and atmosphere. For Burra, that means a careful selection rather than a catalogue raisonné. For the visitor, it means the rare gift of attention span. Compare, for instance, this exhibition: also a pairing but displayed together, in a manner that sometimes felt strained. Perhaps they would also have benefitted from splitting rather than sharing space.

It’s a small intervention, but a smart one. Let’s hope it sets a precedent. If Tate’s vastness can sometimes flatten the artists it houses, this structure lets them speak for themselves.

Outsider in Plain Sight: Edward Burra’s Idiosyncratic Vision

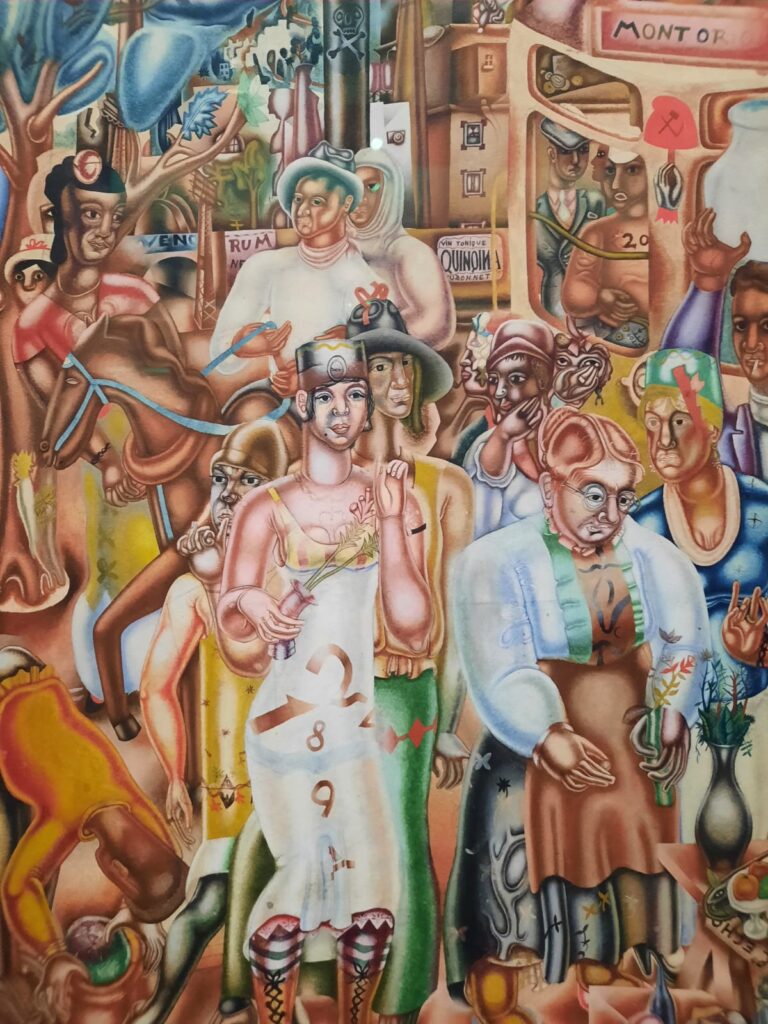

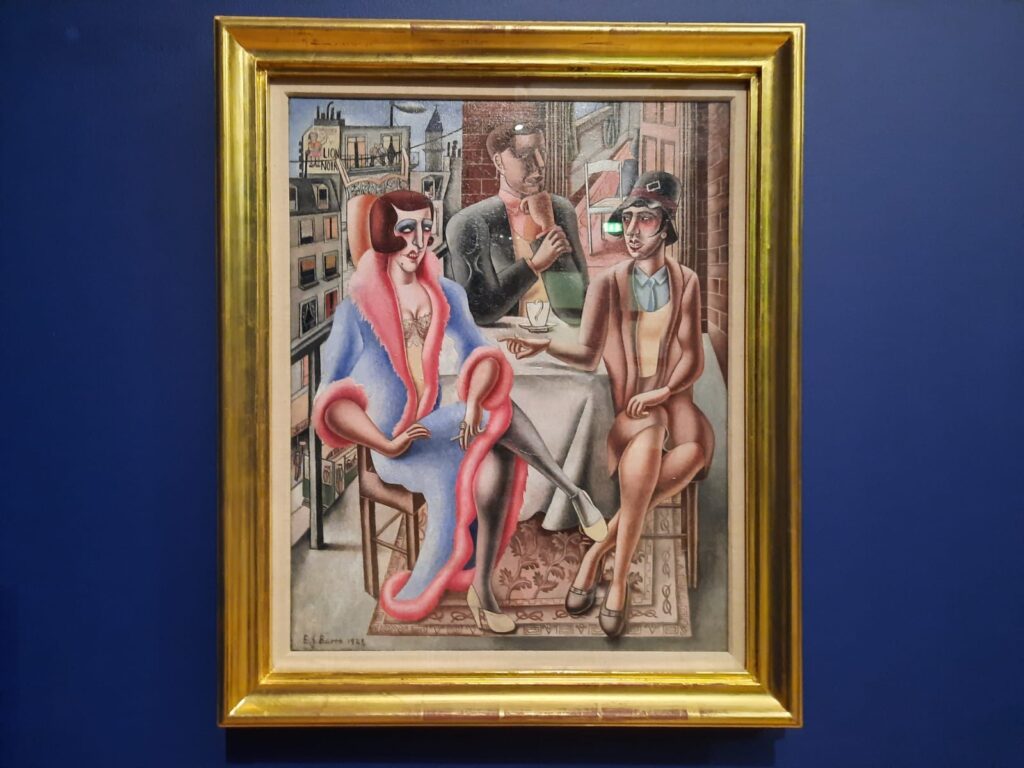

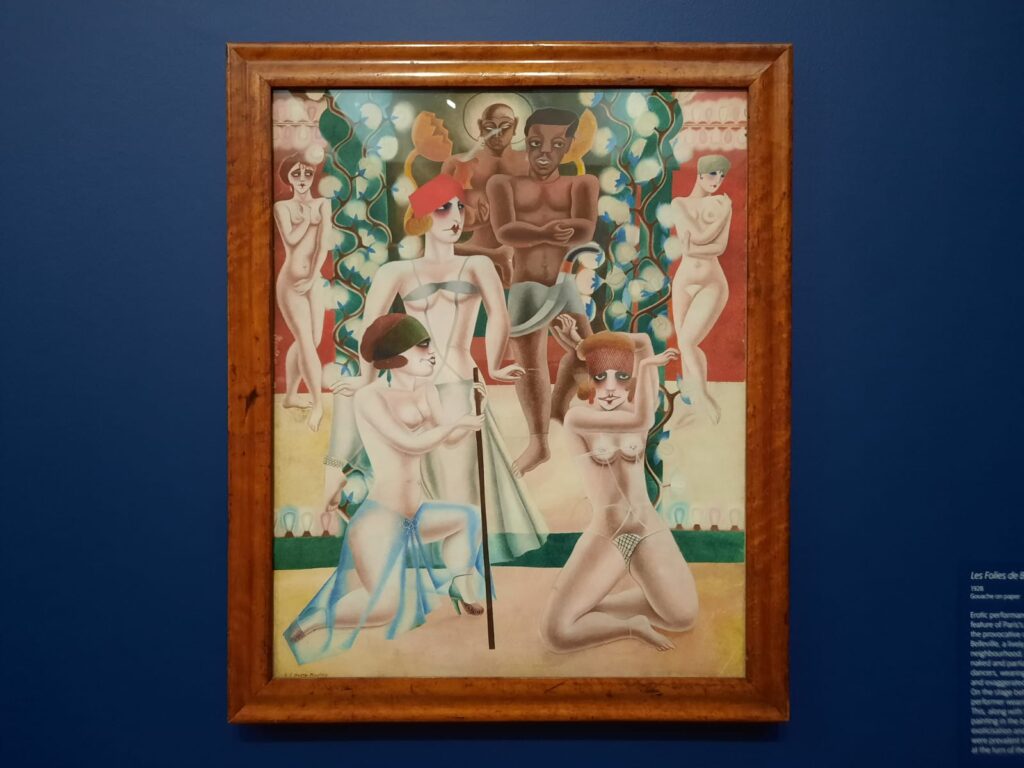

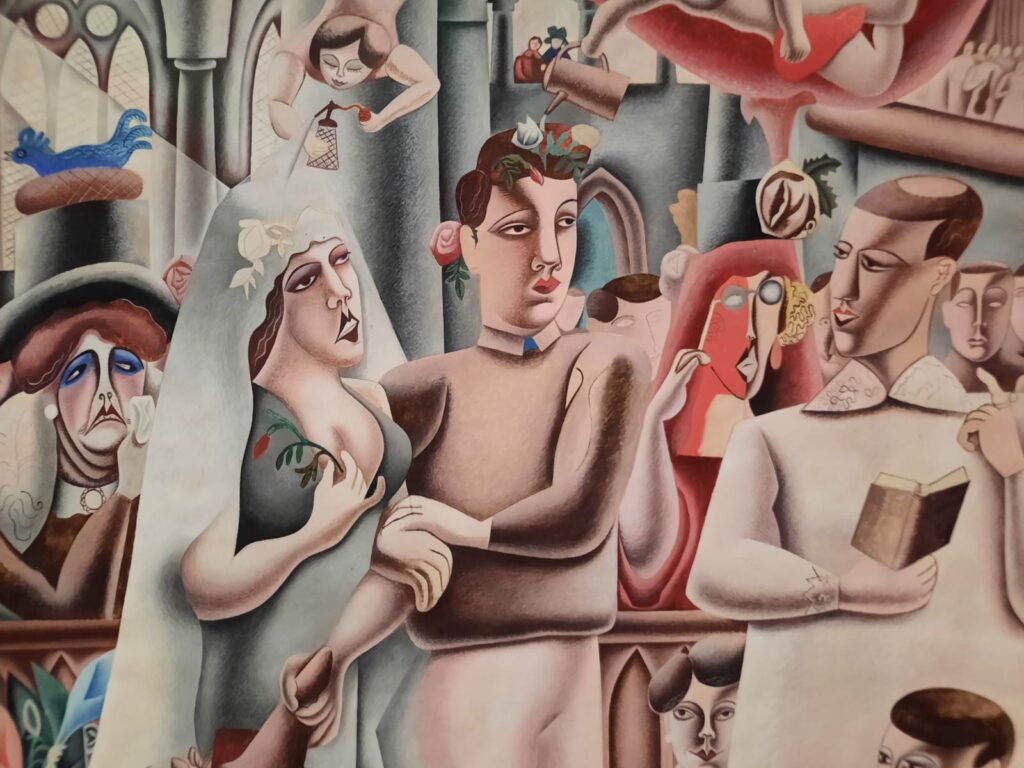

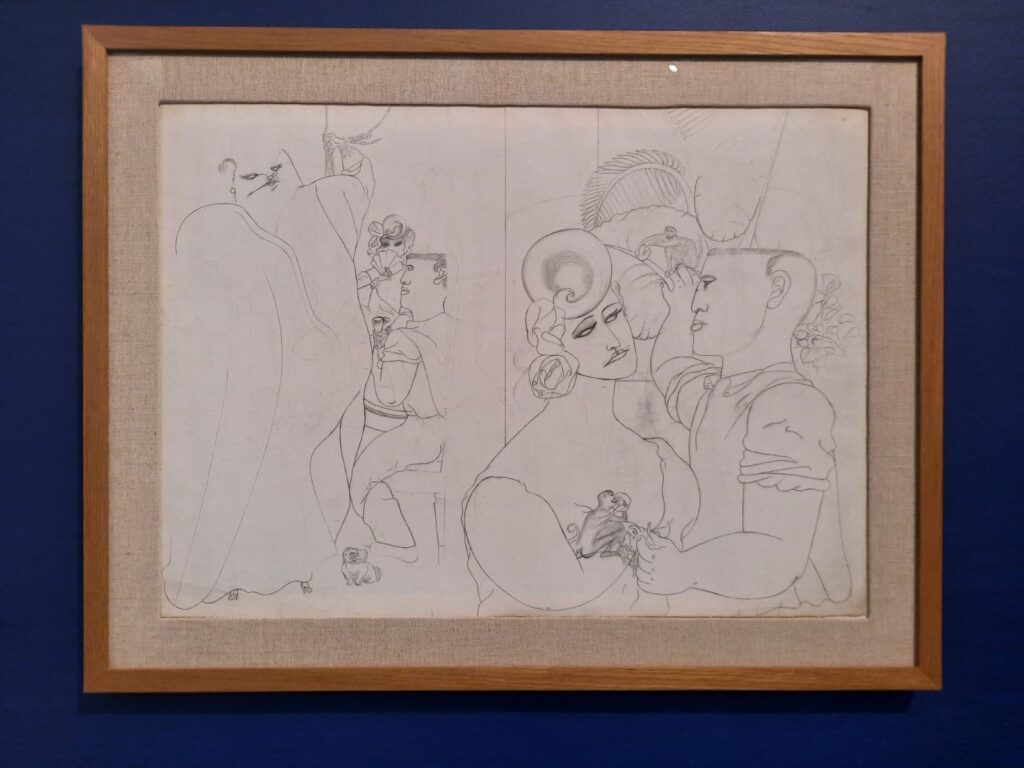

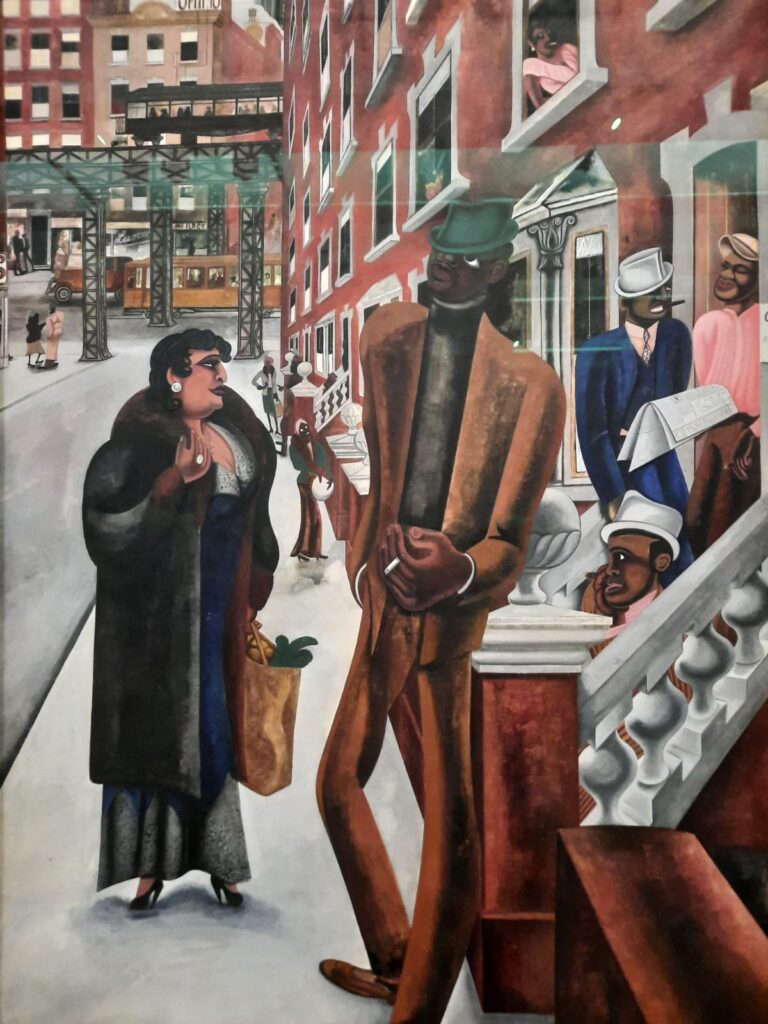

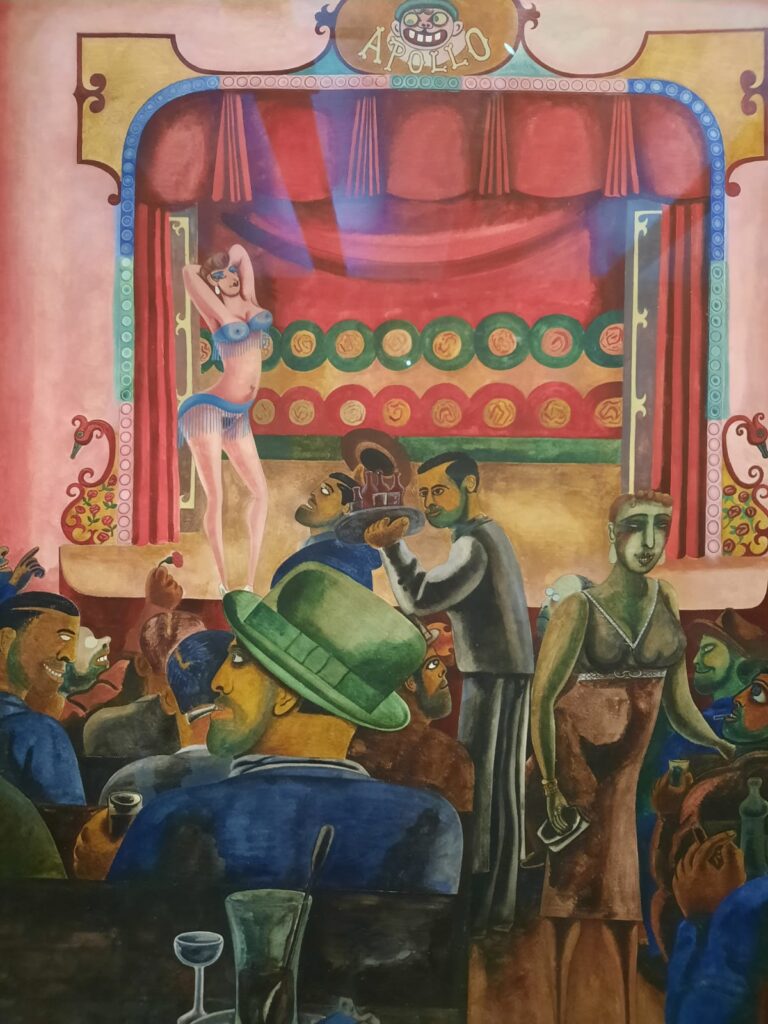

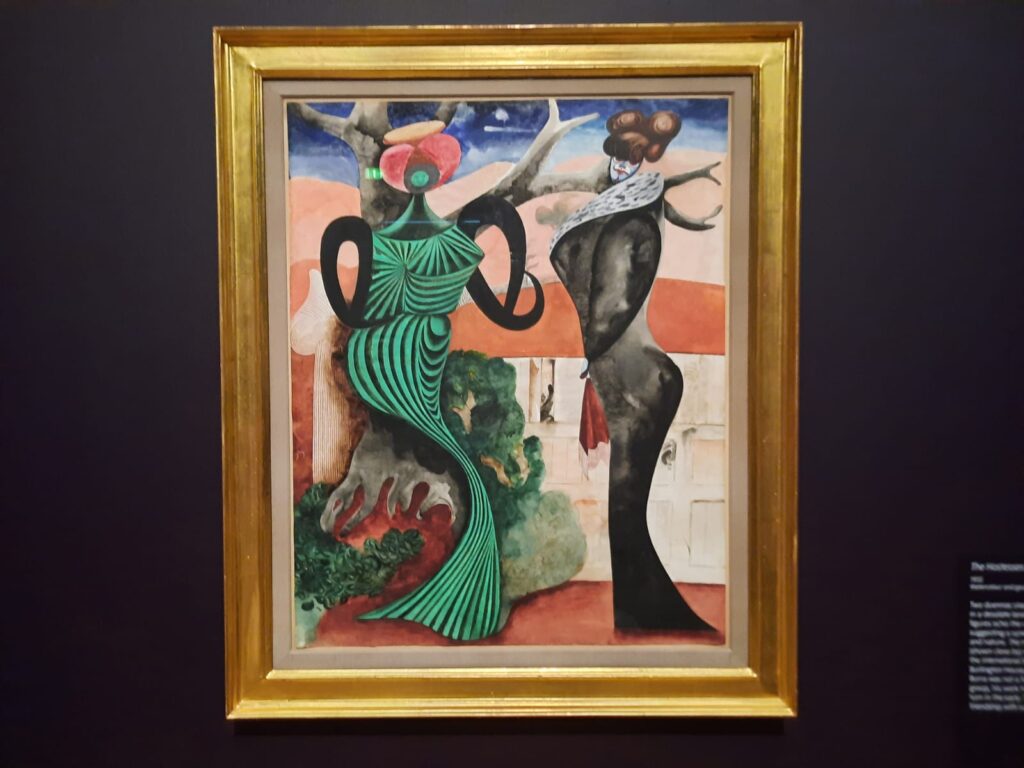

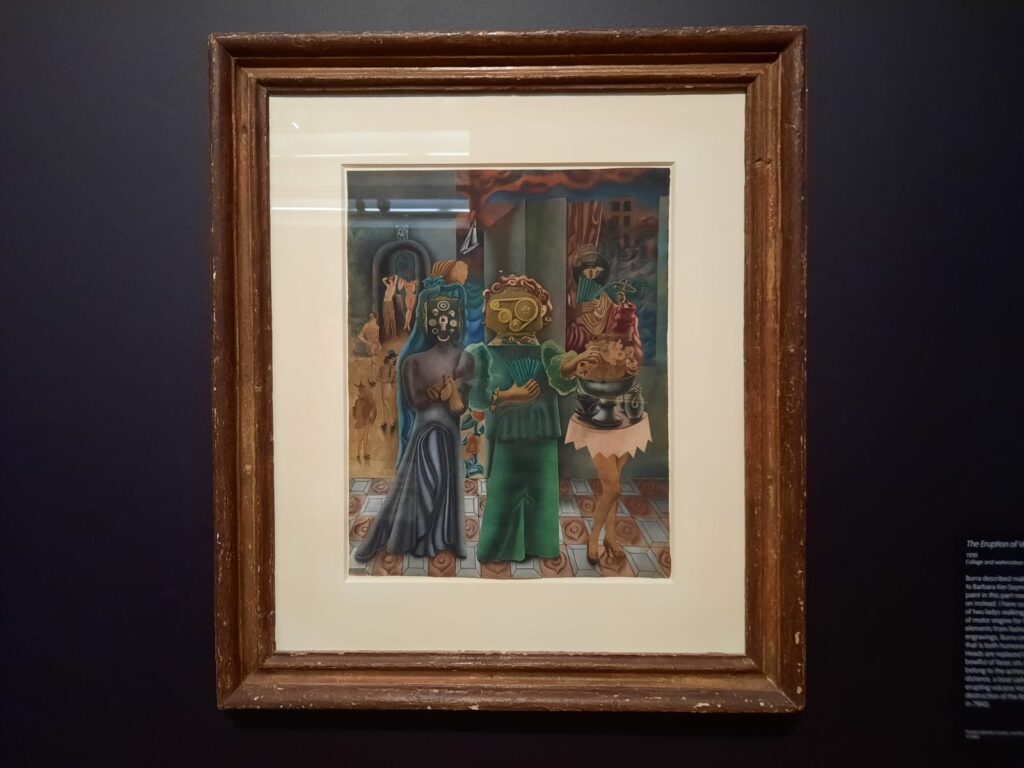

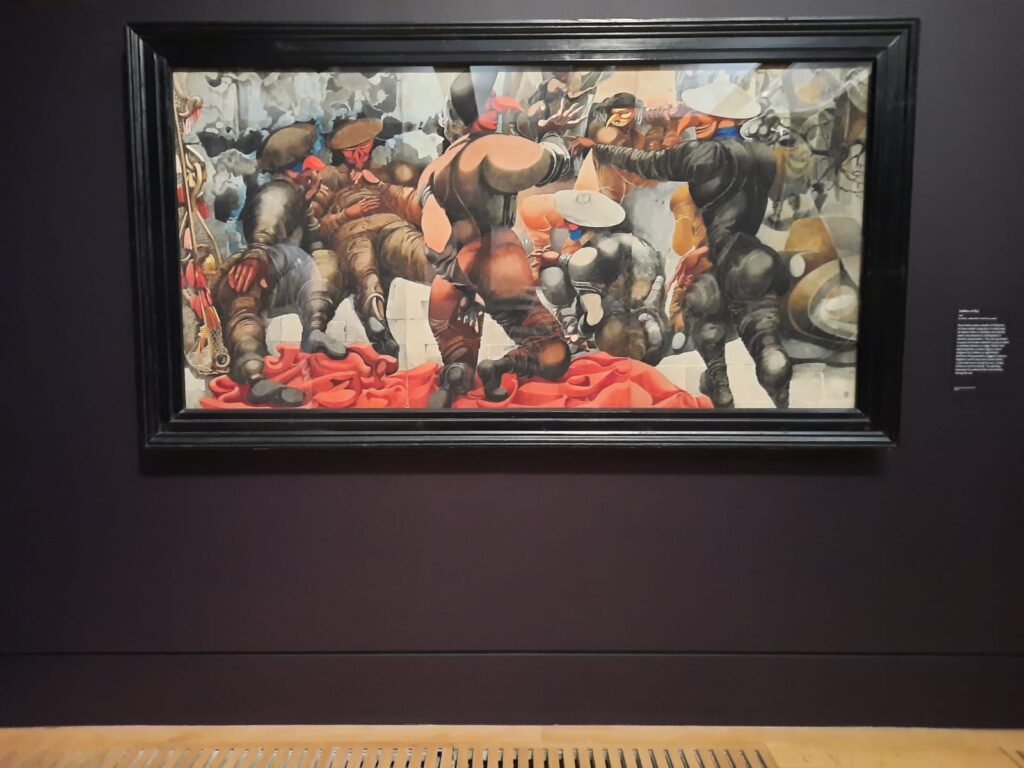

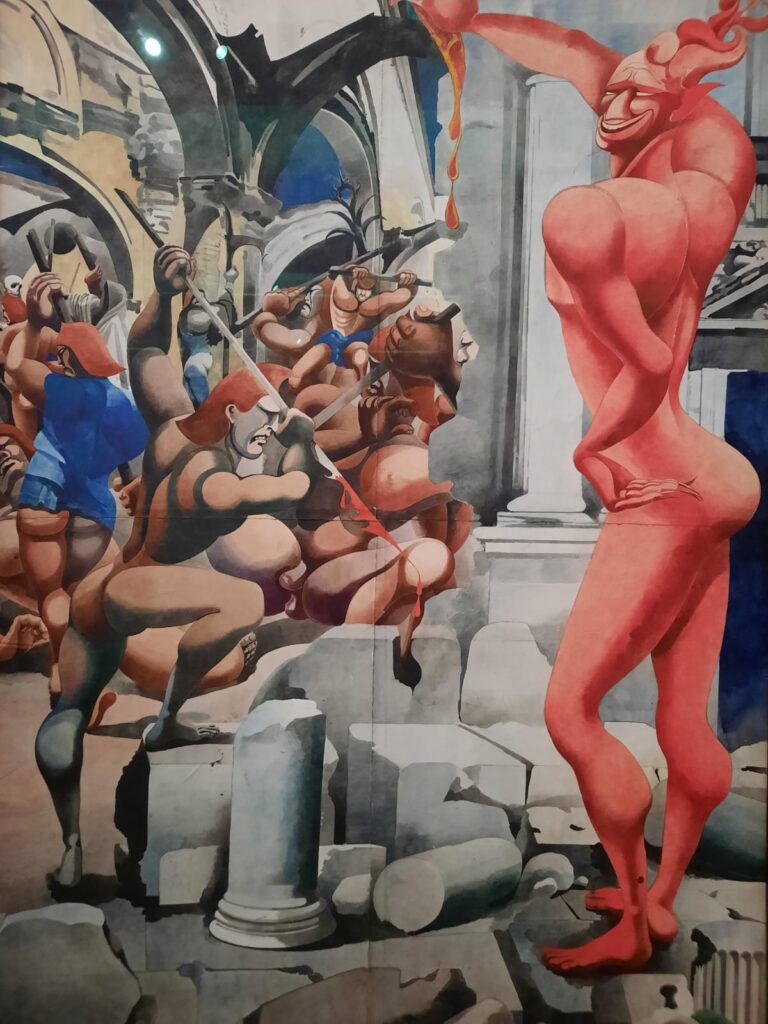

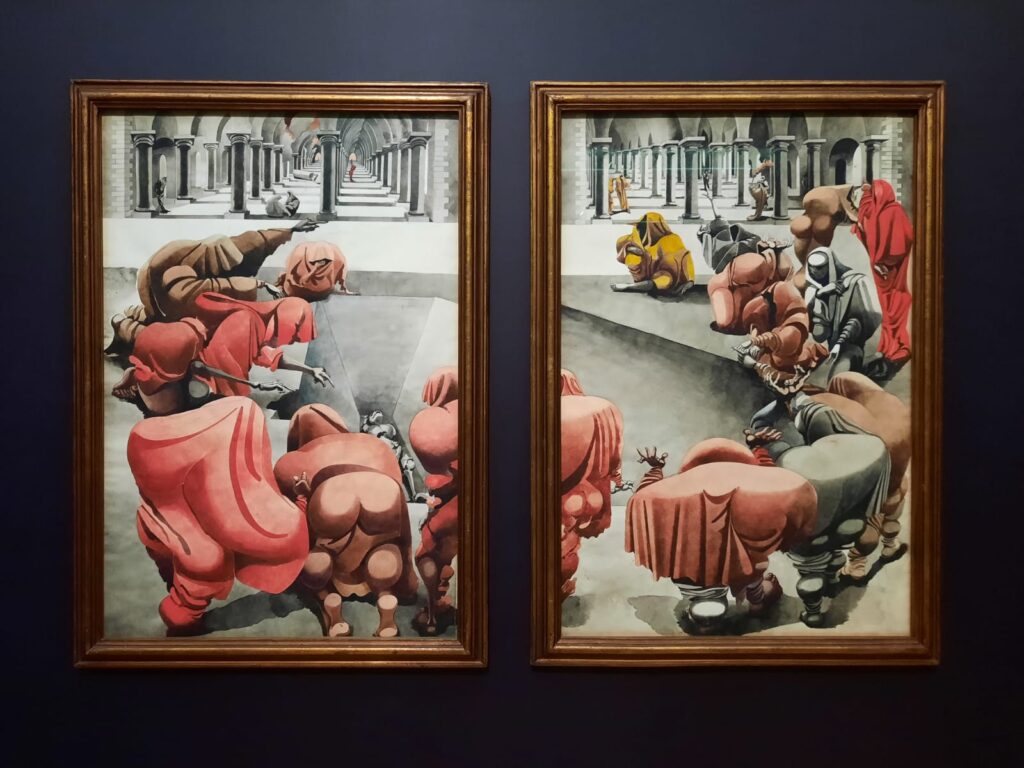

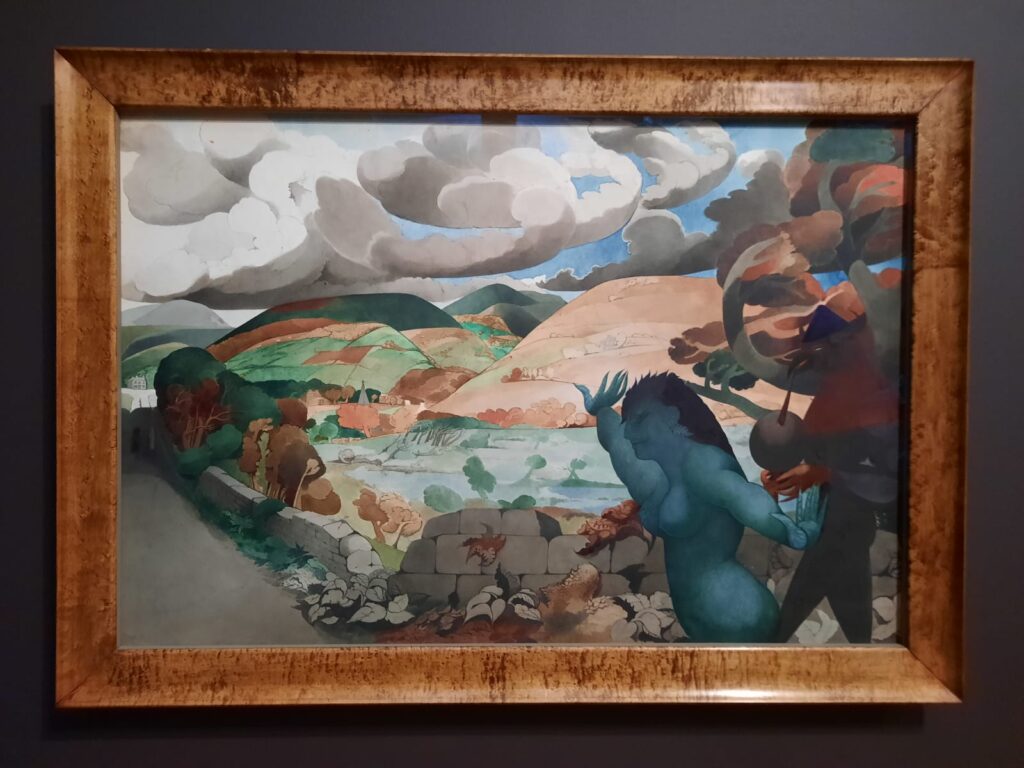

Edward Burra is not quite a household name, though maybe he should be. His work resists easy classification, shifting between satire, surrealism and the social documentary tradition, while always remaining distinctly his own. Born in 1905 to a middle-class family, Burra lived much of his life in Rye, Sussex. He trained at Chelsea School of Art and the Royal College of Art before establishing himself in the 1930s with hallucinatory, figurative watercolours. His paintings, often teeming with sailors, dancers, workers, and underworld characters, have a sharp but humorous observational quality.

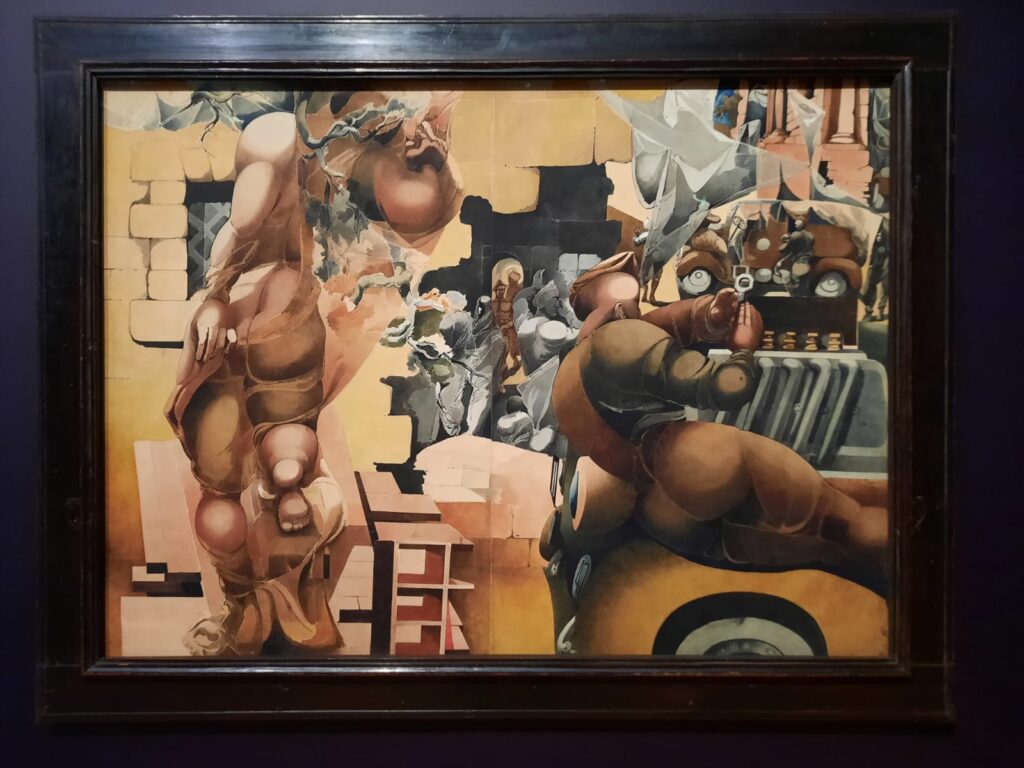

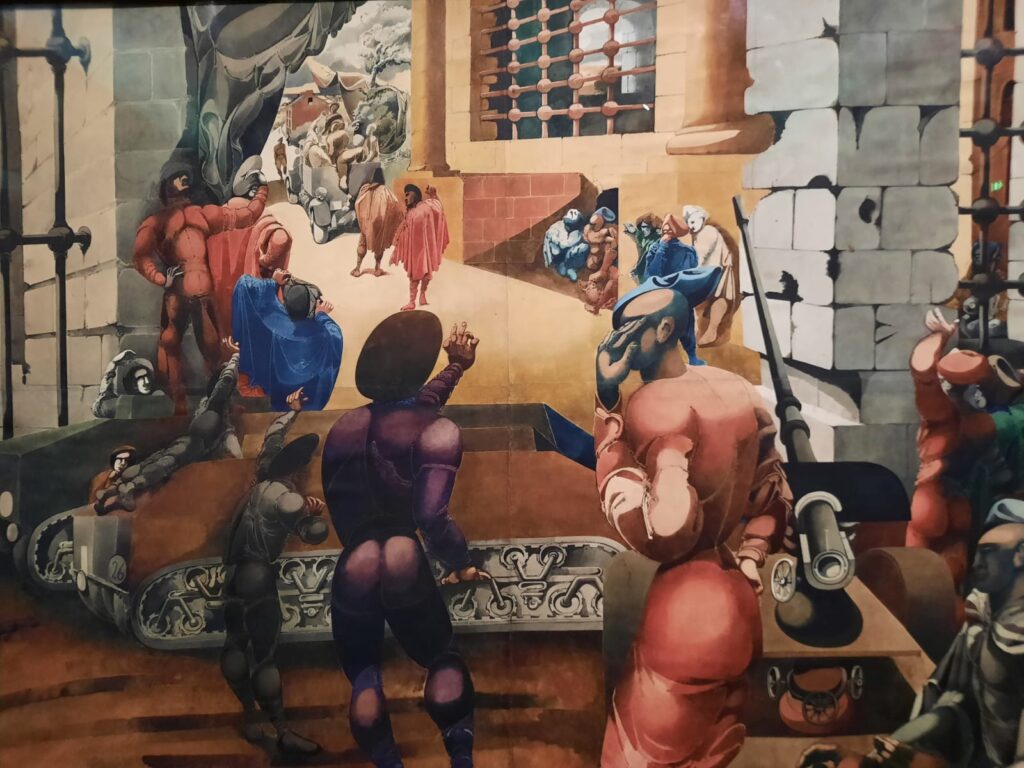

There are echoes of Léger in his early compositions: bold outlines, sculptural bodies, a fascination with modern life and mechanised form. And more than a little of Georg Grosz. Later, in the wartime pieces, you might sense a touch of Tanguy in the eerie, anonymous figures and shifting planes. But Burra was never quite aligned with movements or schools. He stood slightly apart in most senses: geographically, socially, and physically.

Much of this distance came from necessity. From childhood, Burra suffered from severe rheumatoid arthritis, as well as other chronic health conditions. He rarely travelled alone, didn’t live independently, and spent much of his later life in relative seclusion. His sister, Anne, became his chauffeur and enabler, driving him through the countryside so he could sketch fleeting vistas from the passenger seat. These journeys became the basis of his later works. The final rooms of the exhibition display bright, flattened rural scenes that at first seem placid, but with a hint of something stranger.

It’s this blend of witty observation and underlying disquiet that makes Burra’s work feel both rooted in place and psychologically adrift. The exhibition does a fine job of tracing this tension.

A Life in Motion: Travels, Theatre, and the View from a Car

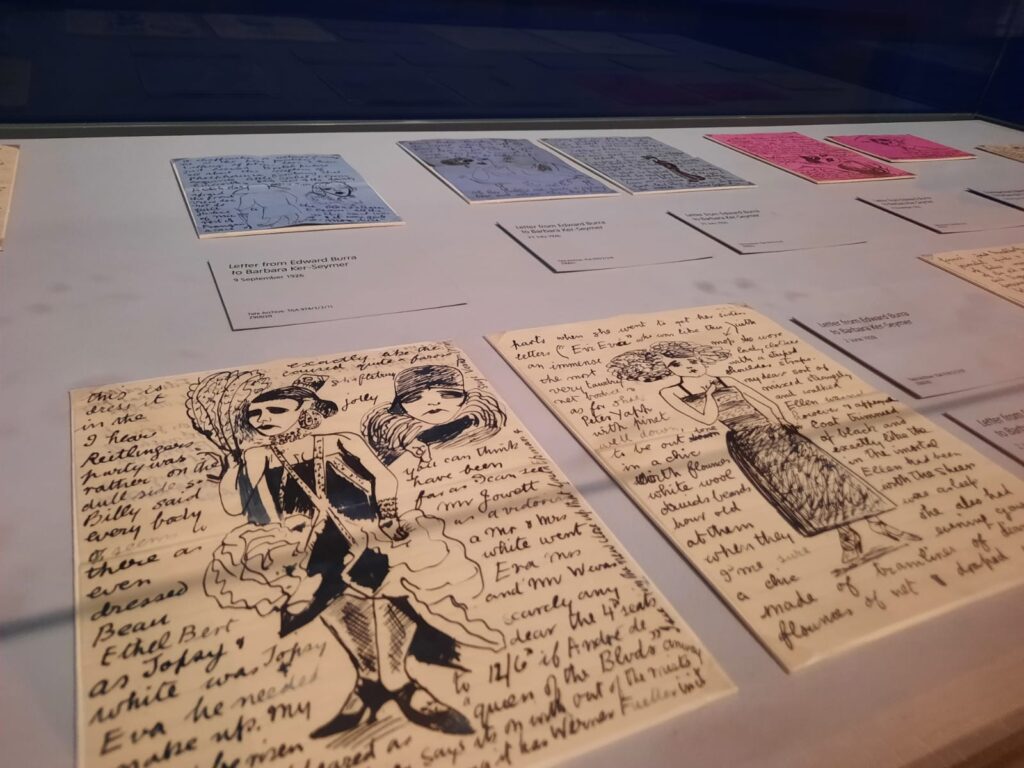

Burra always seemed to be in the right place at the right time in the early years of his career. He saw Josephine Baker dance in Paris before she was famous. He was in New York for the Harlem Renaissance. Then in Spain just before the Civil War broke out (although, unlike most of his artistic peers, he was initially on the wrong side of history, expressing early support for Franco). Around these travels, he maintained a robust social circle of artists and writers, particularly Paul Nash, with whom he collaborated on collage. These early decades were productive and richly observational: the works on paper from this period are astonishingly vivid, full of atmosphere, character and minute detail. You could spend ages in front of any one, just taking it all in.

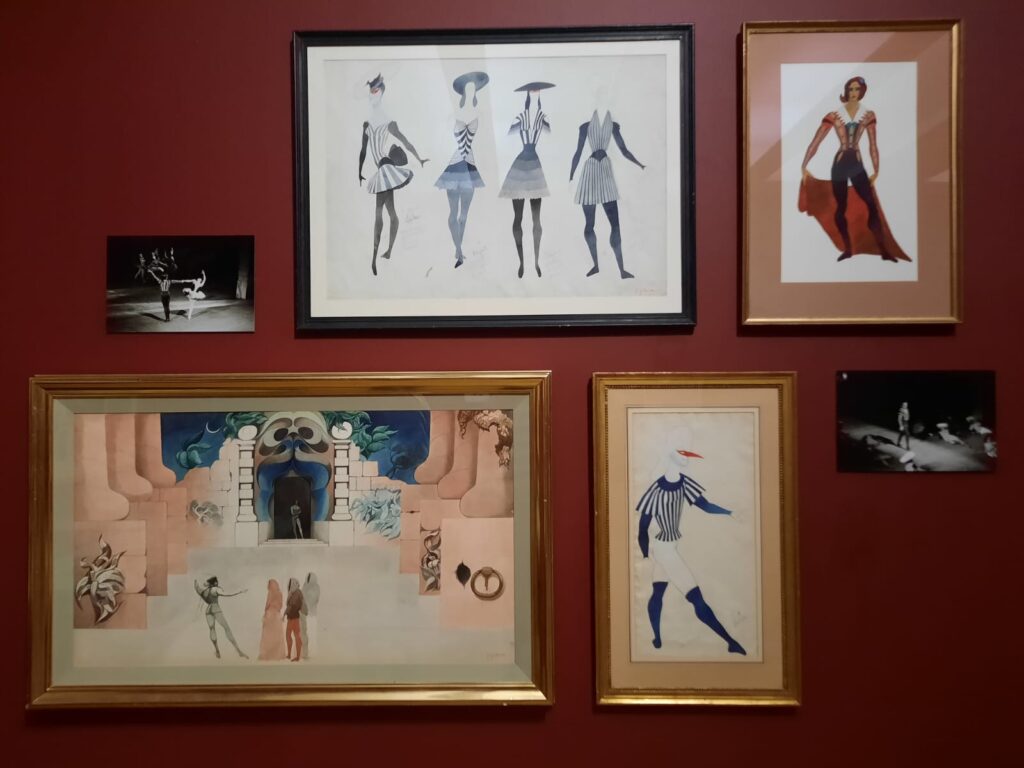

From the Second World War, things changed. Burra could no longer travel. International trips were impossible, and the Rye coast was considered a strategically sensitive zone (the labels are a little unclear here, but there’s a sense of constrained movement.) Instead, Burra turned to the theatre, designing sets and costumes with great success. These feel like the worlds of his paintings brought to life: lots of rich detail in a visually cohesive whole.

And then come the landscapes. After the war, unable to travel alone, Burra’s sister Anne would drive him through the countryside so he could sketch what he saw. These later works are something of a stylistic and thematic shift: hedges, pylons, signage and clouds. But still with that careful eye for shape and the ghost of human presence.

A Still-Enigmatic Artist

One of the curious things about this exhibition is how little we learn about how Burra developed his style. His visual voice changes over time. We can see that clearly, from the grotesque and Grosz-esque forms in the early works to the more abstracted figures of the wartime years, and finally the cool horizons of the late landscapes. But we don’t really get a sense of how or why these shifts occurred. His style doesn’t so much emerge as arrive in the exhibition’s first room, already distinctive and assured. No awkward student work here, just 1920s France, fully realised and humming with life. It’s striking, but means Burra as an artist remains hard to reach.

And Burra remains somewhat enigmatic throughout. The glimpses we get of his worldview (conservative in some ways, queer and subversive in others) hint at contradictions that the exhibition doesn’t really explore. There’s something almost too easy about the chronological, geographical curation. I wondered what might have emerged with a more thematic approach. Or something that engaged with his politics, humour, or inner life more directly. And one would think, given the Tate hold his archives, they would be in a position to get under the artist’s skin a little more.

Still, the multi-sensory elements go a long way towards filling in the cognitive gaps in the experience. The Harlem room includes a playlist based on Burra’s own record collection: early jazz, blues, things he collected and loved. It adds warmth and depth to already vibrant paintings. Likewise, the stage design room features costume sketches, fabric samples, and archival images, all presented against a background of Carmen and other operatic works. It’s not something the Tate often do (with the odd exception, like a sample of Schönberg in their Expressionist show) but here it’s used well: evocative but not overbearing.

Final Thoughts on Edward Burra

We may not get especially far below the surface with Burra, but what we’re shown is absorbing and, crucially, keeps us engaged. And perhaps that’s enough, at least for now. Burra is not a household name, and there’s a case to be made that this tight, focused selection is the better introduction. A more exhaustive survey would likely mean a return to Tate Britain’s vast and draining format. And then we’d be right back where we started: tired and grumbling about gallery bloat.

This exhibition doesn’t attempt to crack Burra open. And while there’s a certain frustration in that, there’s also space for further interpretation. A future show might shift from the retrospective model and try instead to get closer to the man himself. His politics, his contradictions, his inner world, his romantic life. But it’s also worth remembering that Burra doesn’t have the institutional gravity or art-market cachet of some of his peers (though a few of his works have crossed the seven-figure mark). What we see here has been carefully assembled from private collections and regional museums. The Tate’s own holdings are oddly weighted toward his skeleton-themed compositions, a strangely narrow window into a varied career.

Still, the pleasure of seeing these works gathered together, many on public view for the first time in decades, is enough reason to visit. Burra remains elusive, certainly, but the glimpses I got left me wanting more.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3.5/5

Edward Burra on until 19 October 2025.

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.