Philip Guston – Tate Modern, London

A well-curated and somewhat delayed exhibition at Tate Modern, Philip Guston is a journey into abstraction and back again.

Content warning: contains discussion of racism and violence.

Philip Guston

I love an exhibition on an artist I know little about. I also love a bit of drama. And so I was happy to finally have the opportunity to see Philip Guston at Tate Modern. It’s on a couple of years later than intended, which is not only pandemic-related. 2020 was a sensitive time. The world had turned upside down. We faced a pandemic on a scale not seen for a century at least. Police violence and systemic racism also came to the forefront with the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Against this climate, the four institutions planning a major Philip Guston retrospective (the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Tate) lost their nerve. They postponed the shows, citing “additional context” required to help audiences interpret the works.

Without a little bit of background information, this controversy is hard to decipher. So let’s do a quick Philip Guston bio. Born Philip Goldstein in Montreal in 1913, Guston came from a Russian Jewish family who had escaped persecution in their home country. The family moved to Los Angeles in 1919. Despite a precarious and difficult childhood, Guston showed an interest in art from an early age, and enrolled in the Los Angeles Manual Arts High School in 1927 where he met Jackson Pollock. Guston did not complete much formal art education, however, and considered himself largely self-taught.

Activism In Art And Life

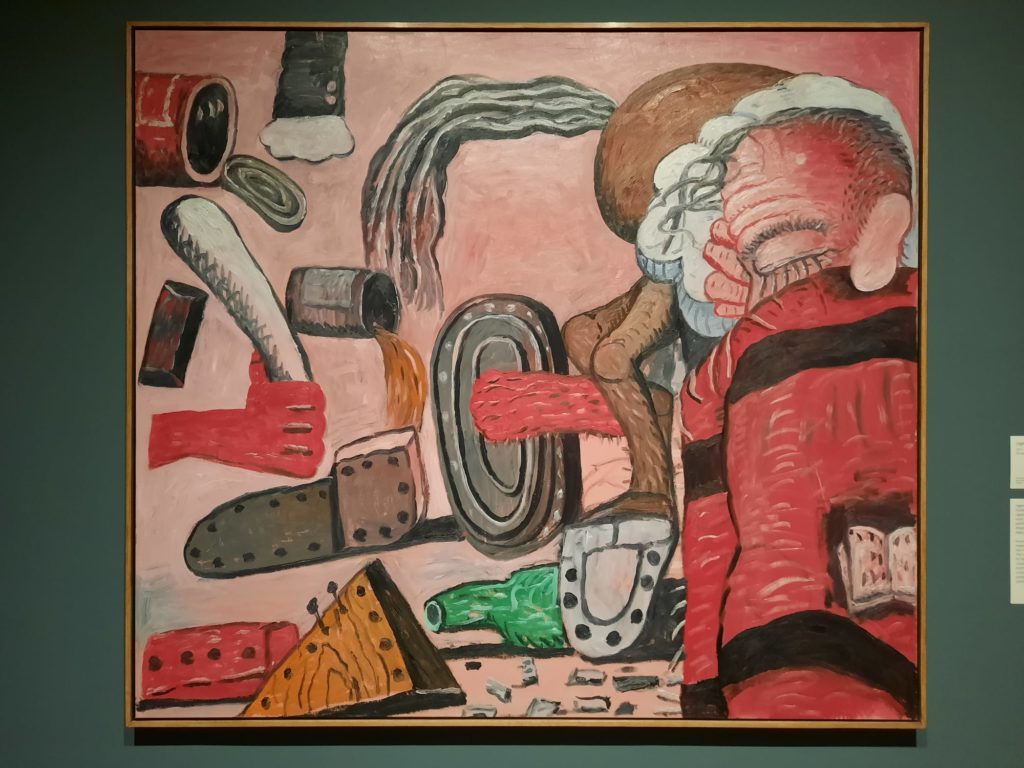

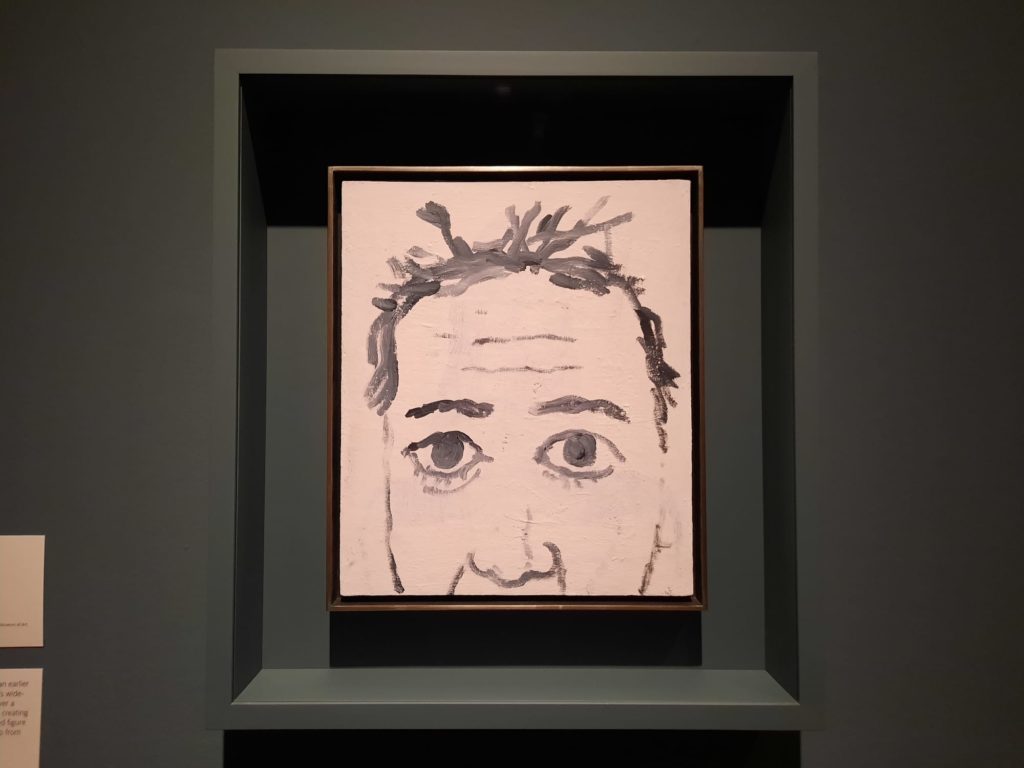

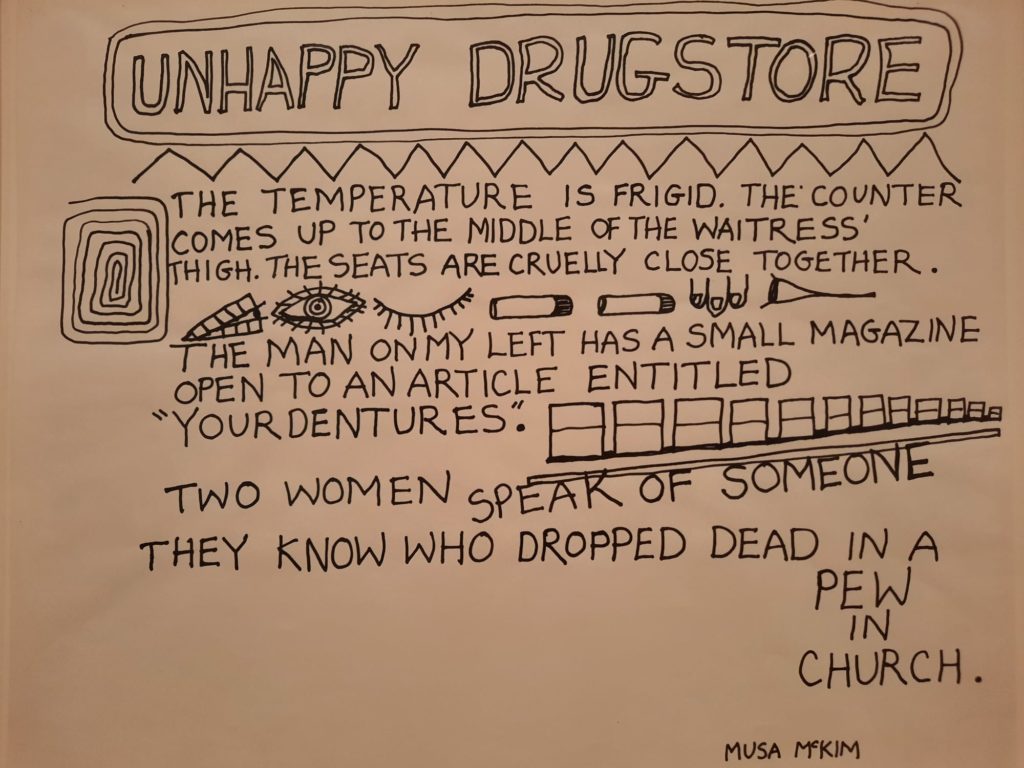

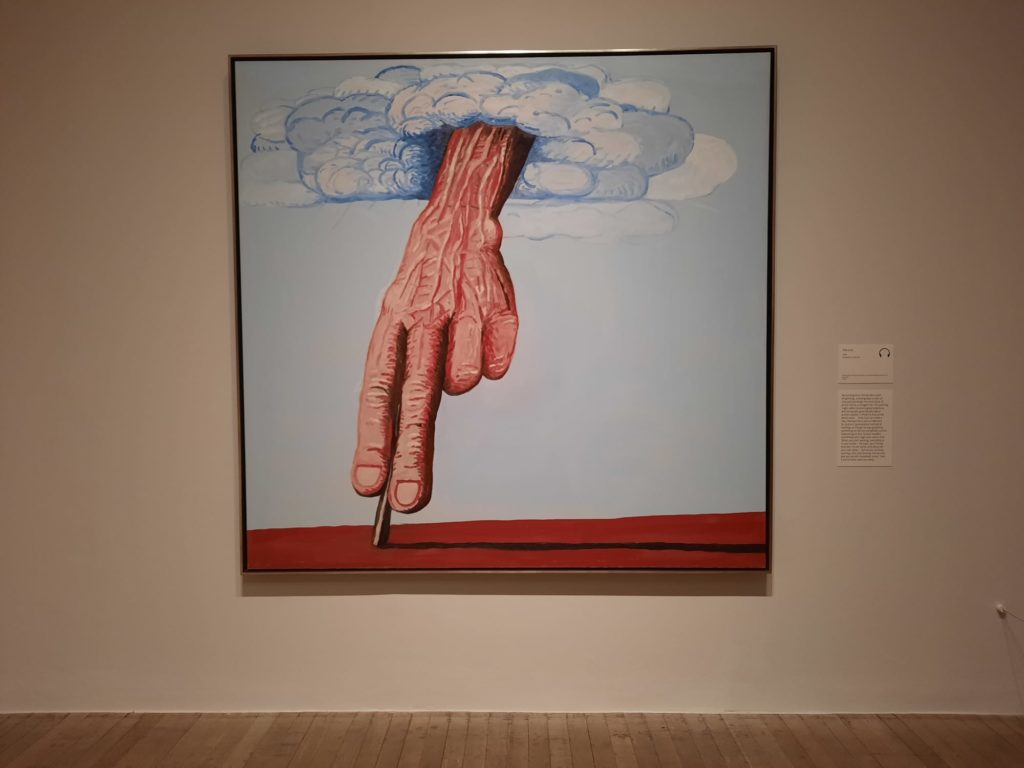

Guston’s age, location and circle (ie. one Jackson Pollock), put him in prime position to be part of the Abstract Expressionist movement. And indeed we see that progression very clearly in the exhibition. But he didn’t stick with abstraction. Instead, from the 1960s, Guston moved back into figuration in a very idiosyncratic way. Since his childhood he had been interested in cartoons. His mature, instantly recognisable style takes this flattened, rounded world and uses it as social commentary. Many of his paintings focus on the banality of evil, the everyday lives people maintain between heinous acts. The reason that those institutions we talked about felt his work needed further explanation? Guston’s visual language included recurring hooded, Ku Klux Klan-like figures.

Imagery of hooded figures and race-based violence is evident in Guston’s earlier work as well. And calling attention to the darker side of society very much aligned with his values. Guston was a Communist-affiliated activist from the early 1930s, helping to raise money for the defendants in the Scottsboro Boys Trial, for instance. He continued to be politically engaged throughout his life. It was the violence against protestors at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago which prompted his return to figuration.

I’ve written before about how the same exhibition can be more different than you would expect when it travels between different institutions. That seems to be the case here. It seems in Boston, for instance, there was a pamphlet written by a trauma specialist to help visitors prepare themselves, and a marked path to avoid the more challenging works. There’s none of that at the Tate: the context-setting is exactly what I would have expected if the controversy had never occurred. Perhaps it’s the particularly American resonance of the subject matter that makes the difference. Or perhaps some institutions are more willing than others to take the risk that it’s been long enough, their audience will understand the context, and not implement any special measures.

On To The Exhibition Now, Then

Yes, let’s actually get down to a discussion of the exhibition and visitor experience now. I thought this was a very well-curated show. It’s in rooms in the Natalie Bell Building which more or less extend one way with a half turn in the middle and then back again. The chronological exhibition is laid out as a journey into abstraction in one direction, and then back into figuration in the other. It does compress some periods in Guston’s career compared to others, but I still found it very pleasing.

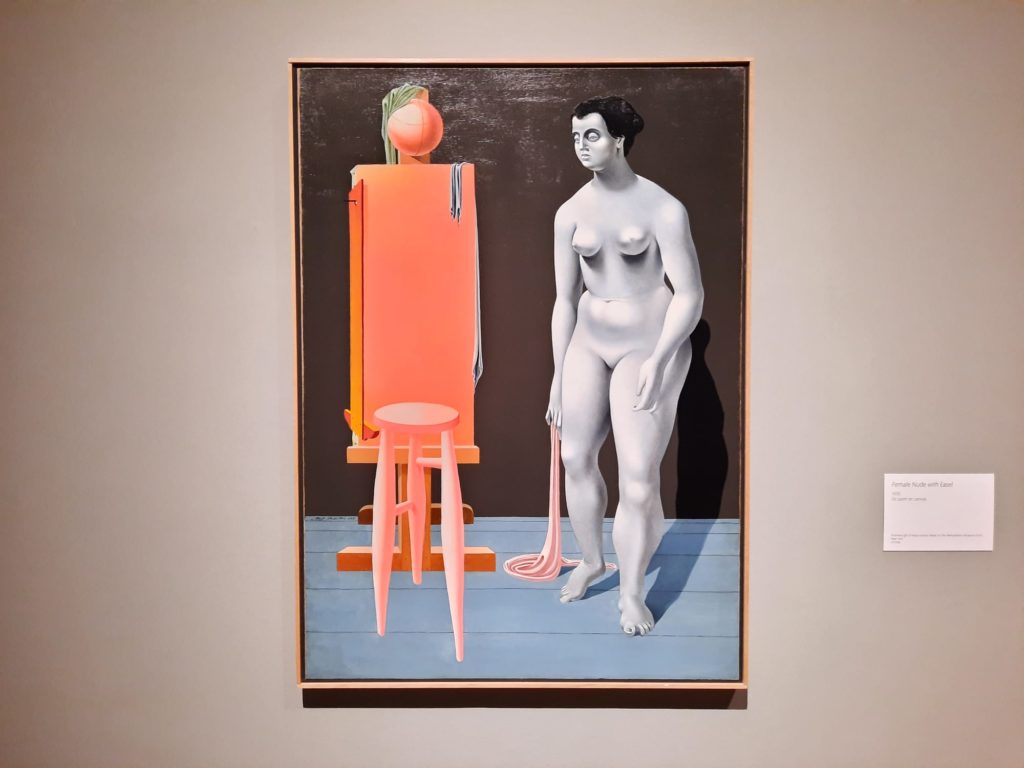

The range of works on view is also excellent. The exhibition starts with Guston’s early works, including forays into Surrealism that are like a combination of Picasso and De Chirico. The curators next have the tough task of bringing Guston’s period as a muralist into the gallery: they do this through documentary evidence and works which speak to his themes and styles at this time. A particular highlight for me was Bombardment (1937), a remarkable depiction of the bombing of Guernica in a tondo format which radiates outward with exploding force.

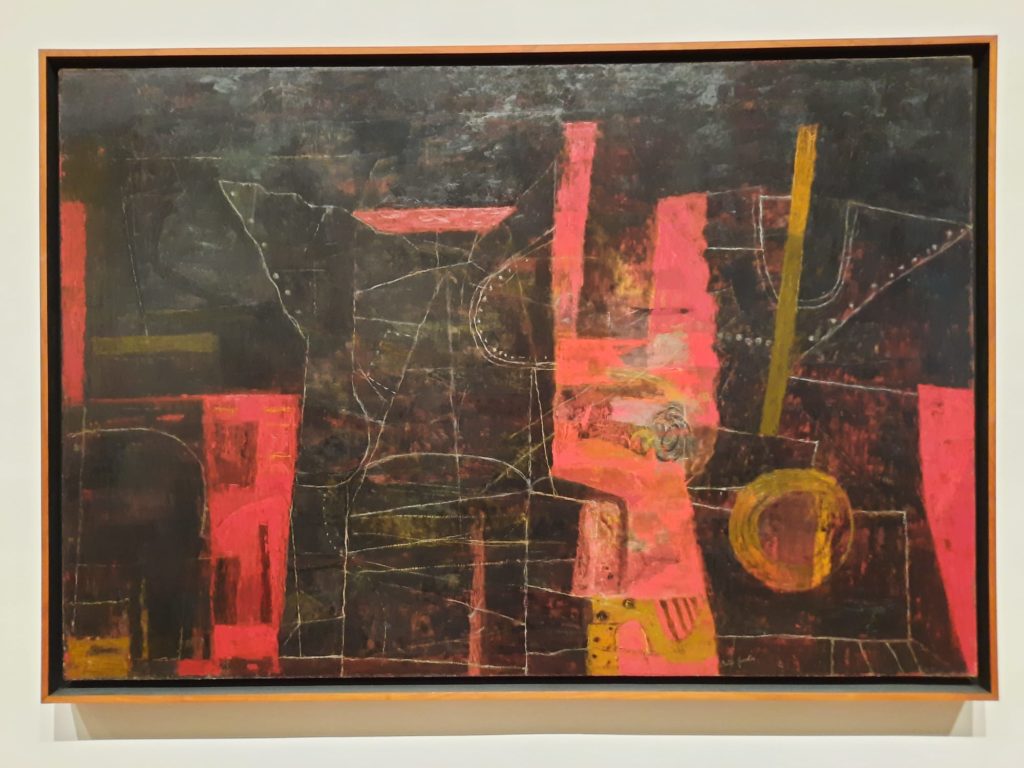

Next are the Abstract Expressionist works. What I found most interesting here was the echo of Guston’s later cartoonish style with its palette of mostly black, white and red pigments. The corridor between the exhibition’s two halves is probably the greatest nod to contextualising and preparing us for the hooded figures to come. And then we have a few rooms of later works exploring Guston’s visual language, techniques and themes. The Tate itself was about the only UK institution I noticed who had contributed works: the others are mostly from American collections, with a healthy number part of a promised gift to the Met by Guston’s daughter Musa Guston Meyer.

A Conversation About America

There are two threads to this journey into abstraction and back. One is about Guston as an artist, experimenting with his craft and either going with or against the prevailing artistic tide at the time. The other is about what sort of dialogue you can have with viewers through different artistic styles.

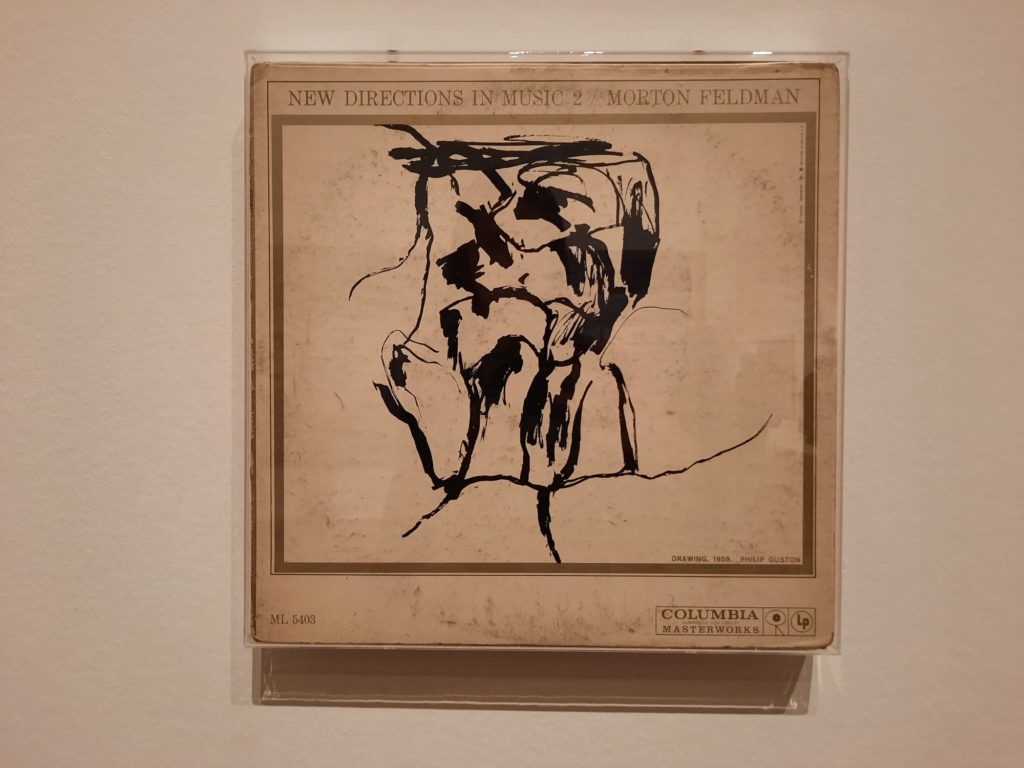

In this exhibition, the former is perhaps a little overshadowed by the latter. Much of the information provided about the rooms and the works focuses on Guston as an outward-looking, politically engaged individual. In fact it’s only really during his time as a muralist that we see any sense of Guston’s interactions with other artists. And that’s pretty unavoidable given the collaborative nature of murals. For the rest of the exhibition it’s just Guston on his own terms. No sense of how other Abstract Expressionists dealt with the same problems of representation, abstraction and technique. We just learn how Guston preferred to work up close for long periods, denying himself the perspective gained by stepping back to look at his canvas. Or how difficult periods in his personal life would drive visible changes in his work.

So this isn’t really an exhibition about Guston within an art world. It’s about Guston and the outside world. As I’ve said, he was conscious of and actively involved in politics throughout his life. Along with his generation he lived through major historic events, in the American as well as world context. And as a Jewish American he was cognizant of the threat of Anti-Semitism, even changing his name in response. What this exhibition shows is how well Guston captured these preoccupations in paint. How he held a mirror up to a complex country struggling with deeply entrenched racism and inequality. How he used the non-threatening medium of the cartoon to say something profound and important.

Final Thoughts On Philip Guston

I think you can tell I liked this exhibition. I appreciate a well-curated exhibition even when the artist isn’t one I know particularly well. And what I can say is that I came away with a much better understanding of Guston and where his signature style fits into his overall body of work.

I will always wonder how the exhibition did change in the years it was mothballed, if at all. Would the focus have been so much on Philip Guston the man rather than Philip Guston the one-time Abstract Expressionist? Hard to say. But I think Guston’s emphasis on the banality of evil is an important message even decades after his death.

This is a much stronger exhibition than some I’ve seen at the Tate this year. I think this is a product of doing a simple idea well. The alternative, which I’ve seen a couple of times at Tate Britain and Tate Modern now, is reaching for a point of view that the artistic evidence doesn’t quite support. These exhibitions tend to be a little disappointing or frustrating, even when I enjoy the art I’m seeing. So I hope to see more like Philip Guston in their 2024 programming and beyond.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 4.5/5

Philip Guston on until 25 February 2024

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.