Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider – Tate Modern, London

Tate Modern’s exhibition Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider is a great opportunity to see a significant part of the Lenbachhaus collection on loan from Munich. But as an exhibition it only really gets going towards the end.

Let’s Start at the Beginning: Expressionism

Unless you’re new here you know the Salterton Arts Review likes to contextualise the art, theatre and sights we see, so today we are going to start with some definitions. What is Expressionism, and what is Der Blaue Reiter? Or The Blue Rider, as the Tate’s exhibition title kindly translates it for us.

We’re going to start with Expressionism. And since this is a Tate exhibition we’re talking about, we’ll go with the Tate’s definition:

“Expressionist art refers to the expression of subjective emotions, inner experiences and spiritual themes, as opposed to realistic depictions of people or nature”

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/e/expressionism

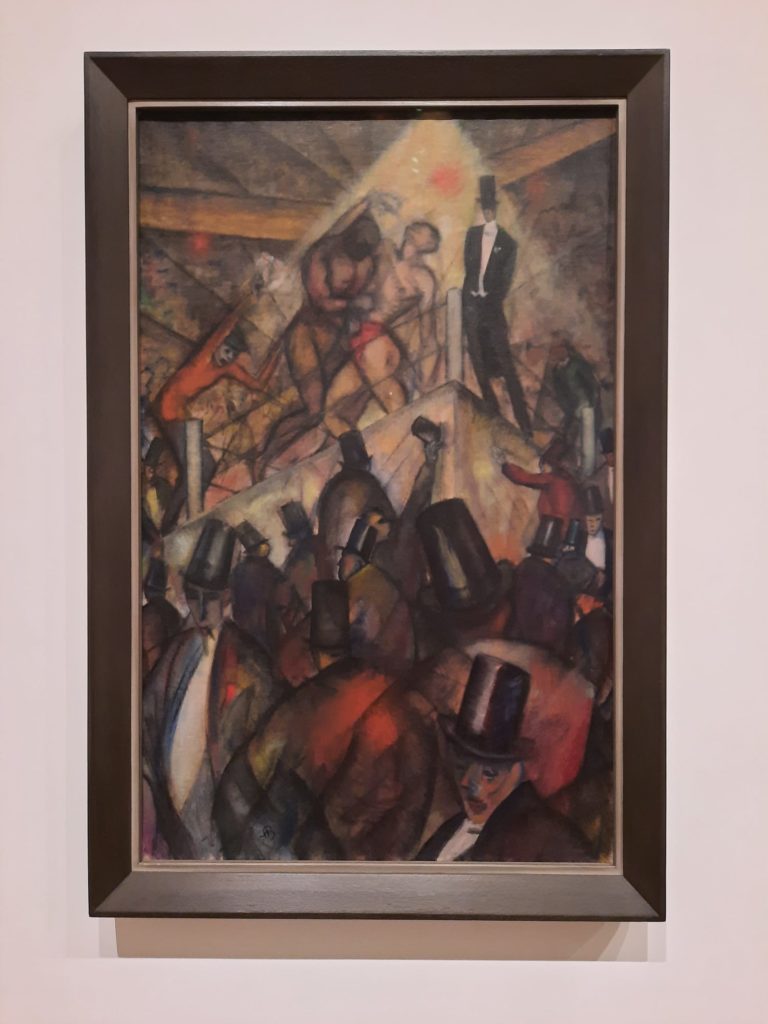

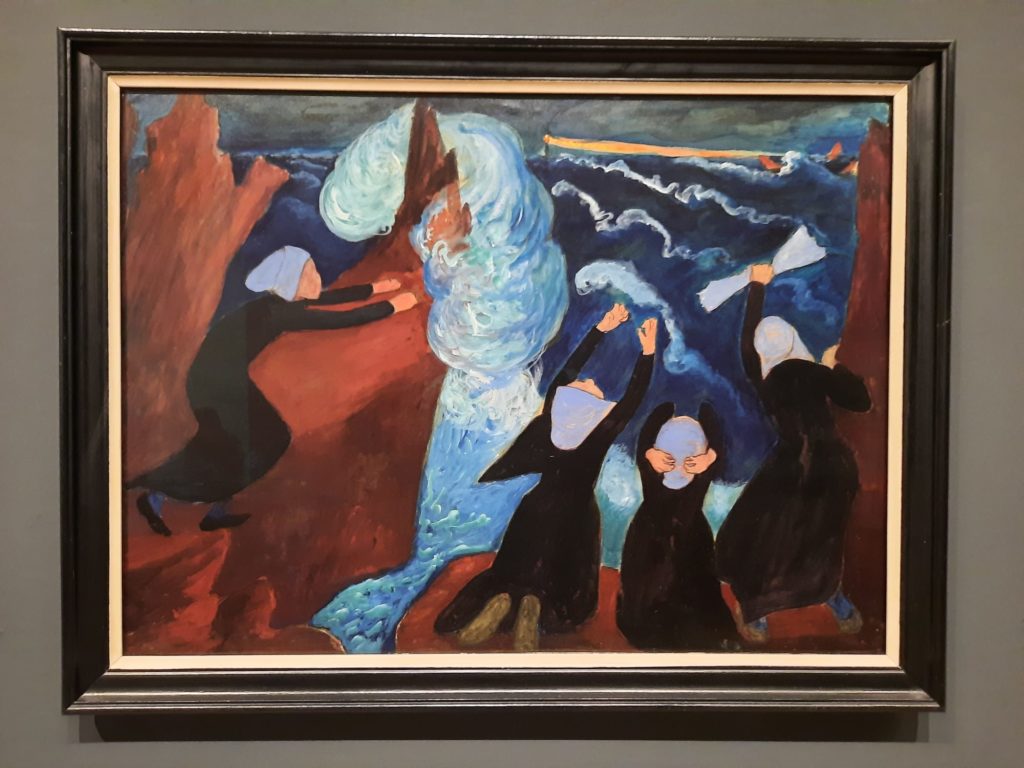

So rather than Impressionism, which is about painting outdoors to capture momentary effects, Expressionism is about painting with an inner eye instead: distorting external reality to capture subjective emotions and responses. Expressionism sprung up in a few places in Europe in the years before WWI. With its often anxious, visceral works, call it either prescience or a reflection of the growing inevitability of war between dying Empires.

But the key thing is that Expressionism was not just one movement. A little before Der Blaue Reiter, there was Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden. Egon Schiele can definitely be considered an Expressionist. Edvard Munch, too. And Expressionism isn’t limited to the plastic arts: writer James Joyce and composer Arnold Schönberg were also Expressionists, for instance.

Der Blaue Reiter

OK. We understand a bit about Expressionism now. And we know that Der Blaue Reiter were one Expressionist group amongst many. But who were they and why were they called that? I’ll answer the second question first, this time. We don’t really know. There are a couple of theories, but nothing definitive. It could be from the title of an earlier painting, or an affinity with riders and the colour blue.

We do know who was part of Der Blaue Reiter, however. Not that it was ever an official group. Der Blaue Reiter was more of an association of various artists in the orbit of a few key people: Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter and Franz Marc. The predecessor of Der Blaue Reiter, if there was such a thing, was the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (N.K.V.M: New Artists’ Association Munich). That was a proper group, including in-fighting and other politics. Perhaps that’s why they needed a break from something so formal.

The Tate very much position Der Blaue Reiter as a trans-national grouping of artists rather than a specifically German movement. This is true. There were several Russians in the mix (Kandinsky, Natalia Goncharova, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin), as well as German, Austrian, French and others (including one American). Their art was experimental, and rooted in spirituality and scientific theories. The spiritual aspect was Christian, broadly speaking (eg. theosophy), although the group also had Jewish members.

It was WWI that put an end to things. The group dispersed, with some fleeing to Switzerland or back to Russia. Franz Marc and August Macke died in combat. But for an informal grouping who were only in business from 1911 to 1914, Der Blaue Reiter had a definite and lasting impact on modern art.

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider

OK, great! We are now grounded in Expressionists and The Blue Rider, and are ready to take a look at the exhibition itself. It is on at Tate Modern, in one of the exhibition spaces in the Natalie Bell Building (as opposed to the newer Blavatnik Building). We’ve been here before, for exhibitions like this one and this one. It’s fairly large, so tends to work well for exhibitions with large-scale works, but exhibitions of smaller works can feel like there’s too much filler. And while this is overall an enjoyable exhibition, it does fall a bit into the latter camp.

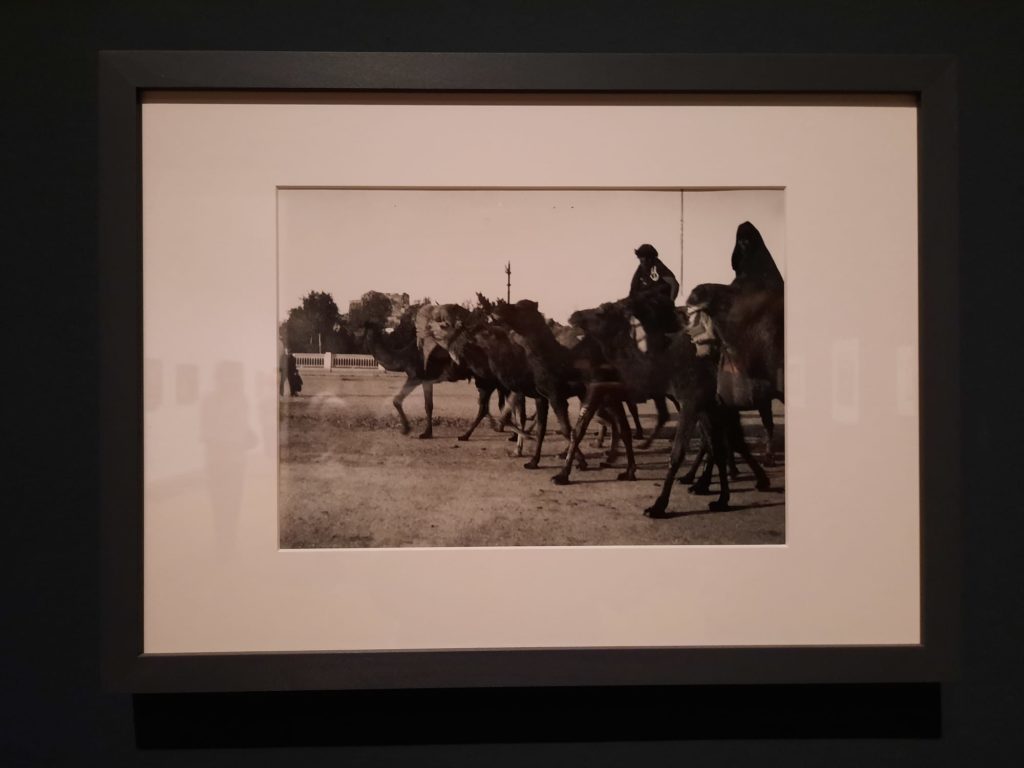

To start off with, I would like to point out something about the title. Typically, when talking about Der Blaue Reiter, the first two names which spring to mind are Kandinsky and Marc. They are the most prominent in terms of the art historical canon, and were also the editors of Der Blaue Reiter Almanach (The Blue Rider Almanac) in 1912. Designed as a Gesamtkunstwerk, the almanac was a manifesto of sorts and is a very important art historical document. But I digress. Because the key thing is, rather than Kandinsky and Marc, the Tate curators place Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter at the centre of the movement. This is borne out by the exhibition design which kicks off with a painting by Kandinsky and photographs from a trip Münter took to the US in 1899-1900.

Why is this important? Well, because it’s also a manifesto of sorts. Or at the very least, sets out the Tate’s intention to do things differently, not least by rethinking the contribution of women. And the Expressionist women have been rather overlooked, historically. There was an exhibition at the RA a while back seeking to redress that, if you recall. Bringing underrepresented artists to the forefront has also been a feature of Tate exhibitions under Maria Balshaw’s leadership. A bit more on this later.

A Worthy Beginning, But Not an Exciting One

I love an exhibition that certain parts of the media might describe as ‘woke’ or ‘political correctness gone mad’, so please don’t misconstrue this next section. For the argument I’m about to make is that the same exhibition opener that positions Gabriele Münter at the centre of Der Blaue Reiter also reveals some of the exhibition’s weaker points. These are twofold.

The first point is that the emphasis on inclusivity and progressive values makes for actually quite a dull exhibition to begin with. There’s a lot of talk in the early rooms about different backgrounds, non-traditional living arrangements and gender identity. But the selections of works are somehow not as exciting as I would wish them to be for such big topics. And what I feel could be more drawn out is the freedom the artists’ social standing gave them. Sure, they were progressive and unconventional. But they were also independently wealthy (for the most part), so making a living from their often strange and intense art was not a necessity. Money also continues to buy a certain leeway for eccentricity today, and certainly did before WWI. In my opinion, the narrative was not quite fully developed here.

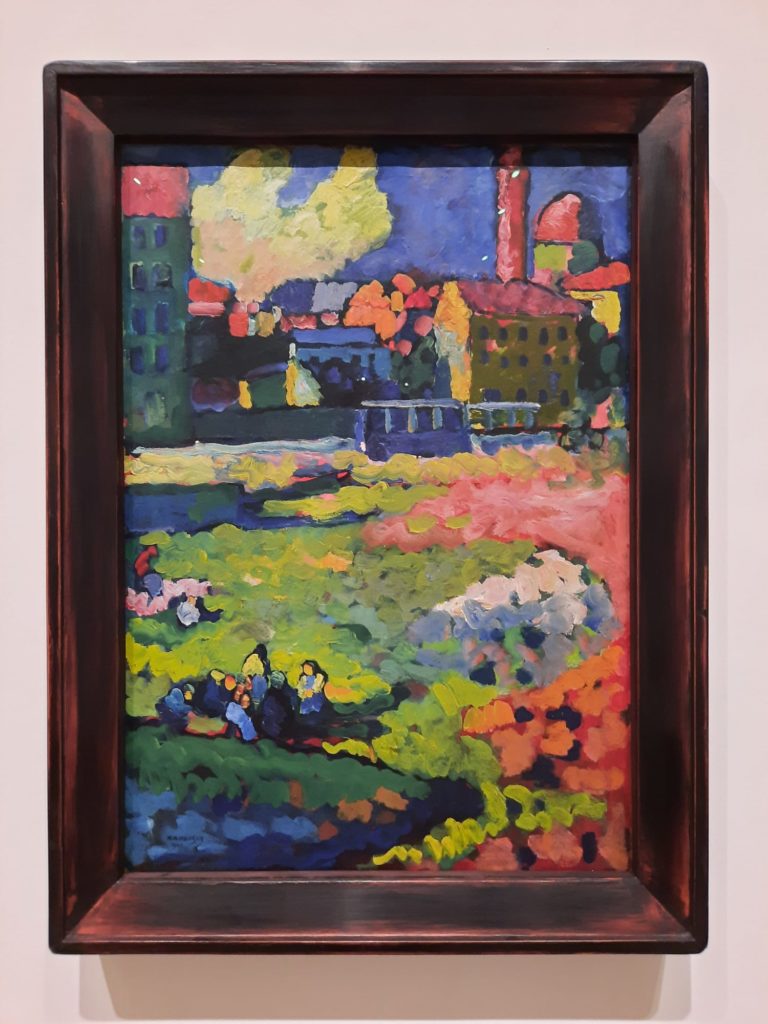

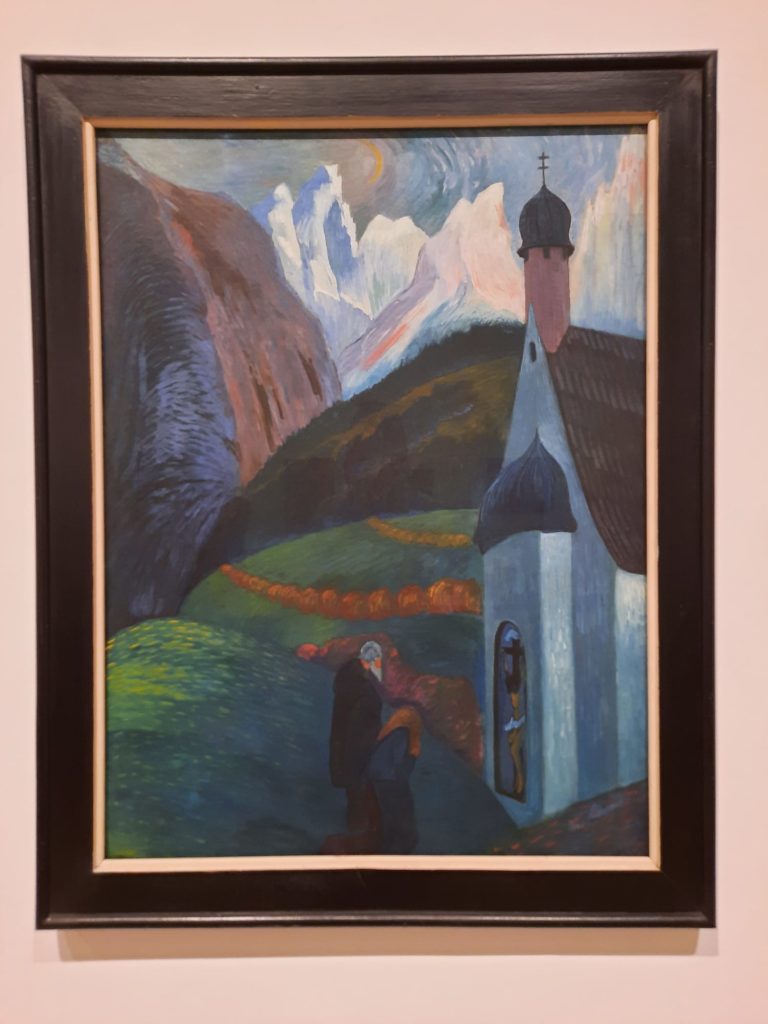

The second point I have alluded to already. It is that, in making these arguments, the works selected for the exhibition are not always those with the greatest visual impact. Let’s take the opening room. Kandinsky’s Riding Couple of 1906-7 is here. It’s a peculiar work: it shows Kandinsky’s experimental side (and Russian-ness), but also looks a bit like an illustration for a fairy tale. Not yet the colour usage or strong emotions I expect from the Expressionists. And Münter’s photographs are an interesting record, but not enthralling. They tell me more about America in the Belle Epoque than they do about what is to come in the following rooms.

A Late Comeback

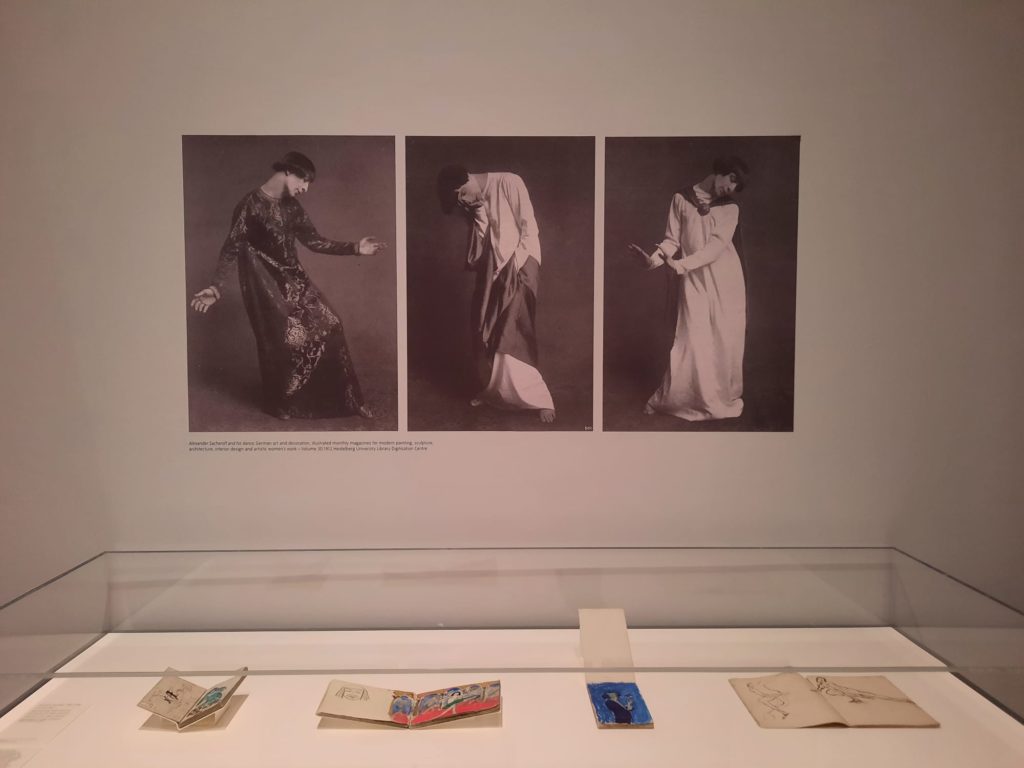

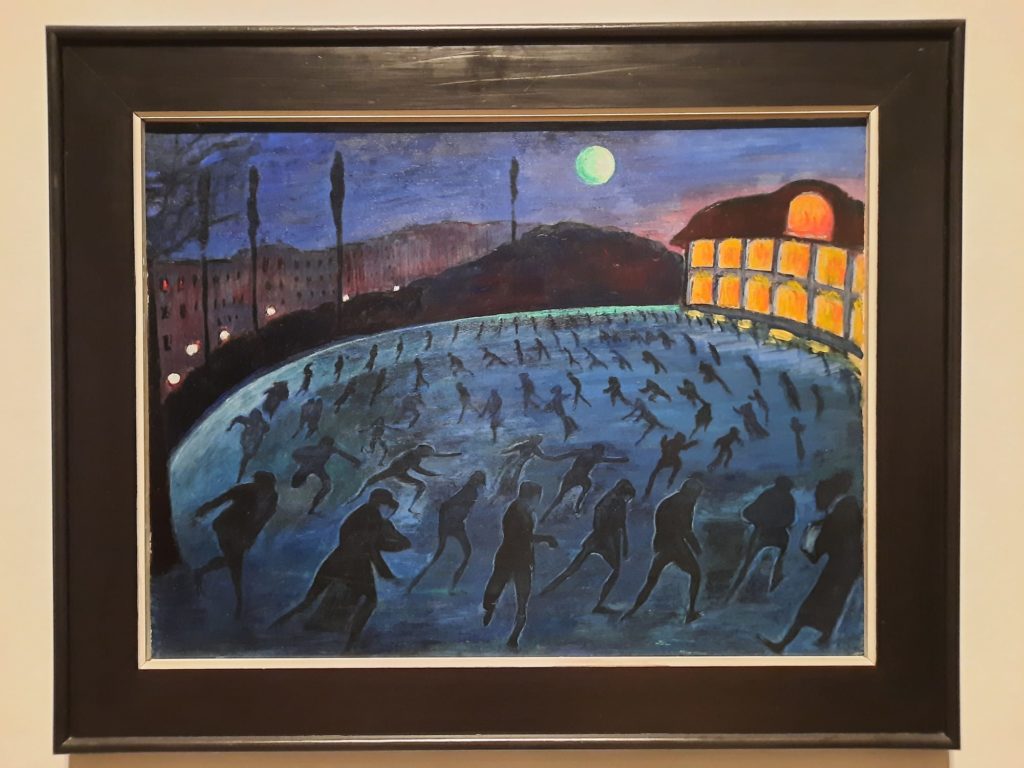

Where things do get interesting is towards the end of the exhibition. Three rooms explore the real contributions of Der Blaue Reiter as boundary-pushing, multi-disciplinary and deeply thoughtful artists, under the banners Sound, Colour, and Light. In Sound, the wall text relates how Kandinsky and Marc attended a concert by experimental (I would say Expressionist) composer Arnold Schönberg in 1911. In response, Kandinsky painted the work we see on display, Impression III (Concert). The painting has plenty of space, and visitors can sit and listen to Schönberg’s music. It’s a synaesthetic kind of experience, and Kandinsky was indeed interested in synaesthesia. “Finally,” I thought to myself, “here is something I can get on board with!”

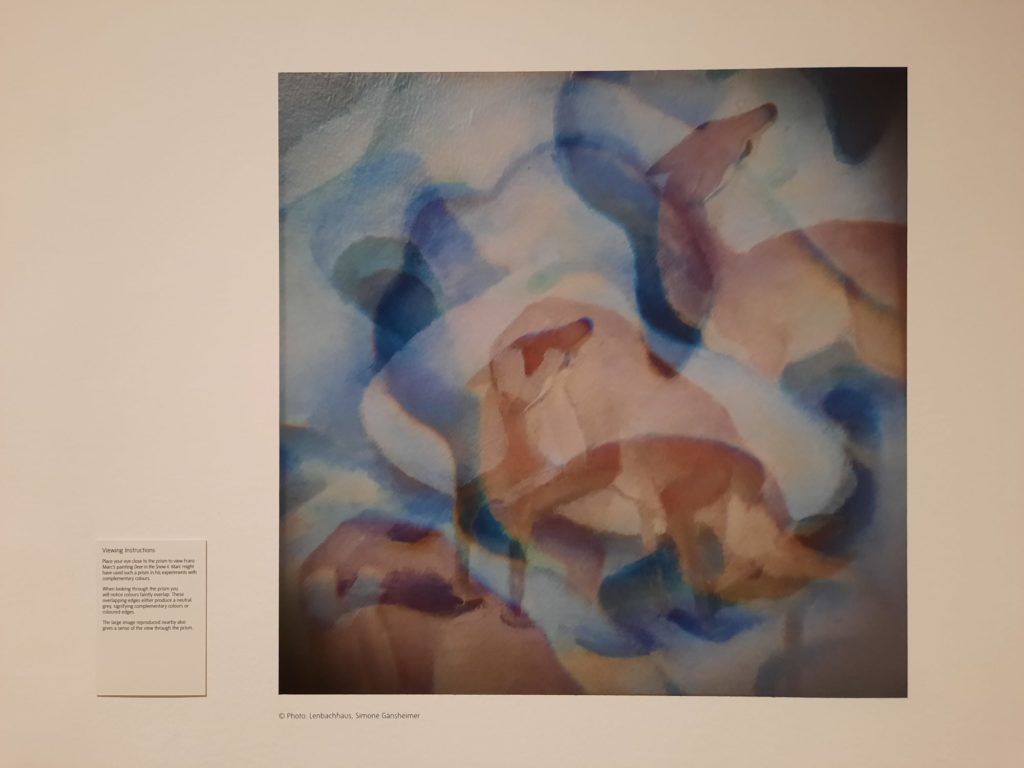

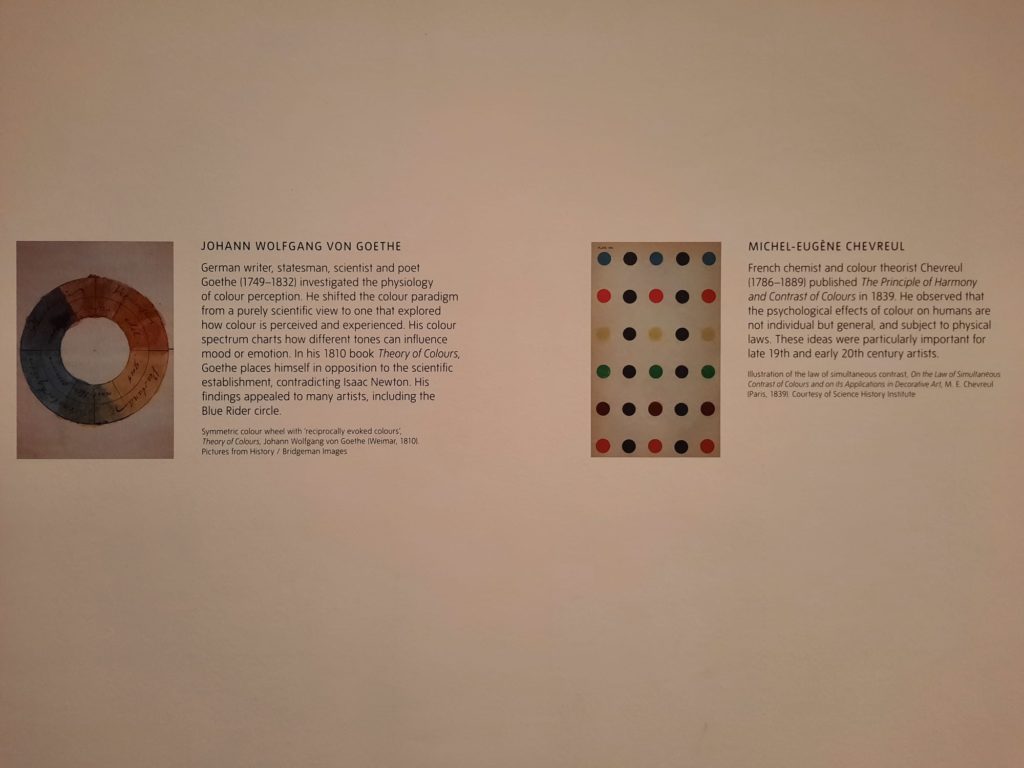

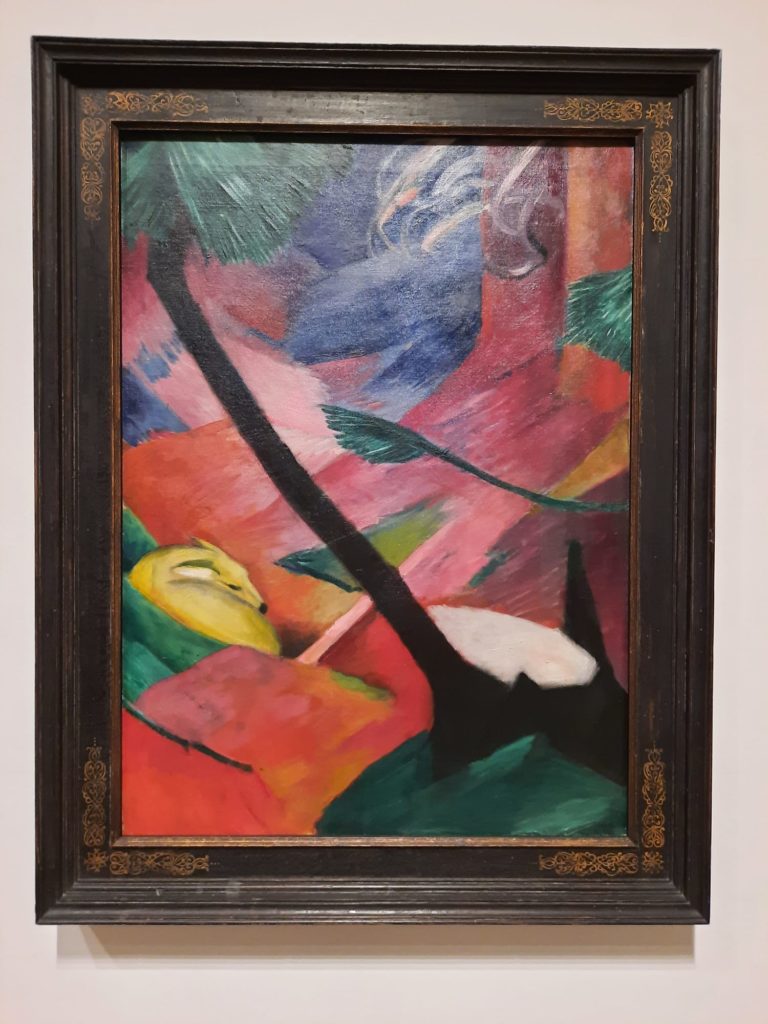

The next room was no less engaging. In Colour, two light refracting prisms are set up, through which visitors can view Marc’s Deer in the Snow II. Marc and other artists of Der Blaue Reiter were interested in the expressive values of colour and form, as outlined for instance in an 1810 text by Goethe, Theory of Colours. Marc used prisms as a way to incorporate scientific experimentation into his works.

And lastly Light. This rooms brings the Expressionists into the present, putting Kandinsky’s Improvisation Gorge into dialogue with Olafur Eliasson’s 2006 work Lichtdecke Kandinsky. Eliasson’s work was originally part of an exhibition at the Lenbachhaus, a response to Kandinsky’s works and meditation on white light in gallery spaces. Over the course of 9 minutes, “various geographical and temporal light conditions” are simulated by a light control system. It can be disconcerting at first, but sparks interesting thoughts about perception, light and colour in art.

Final Thoughts on Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider

If there had been more of the experiential and theoretical side of the exhibition, I would have said it was top notch. As it stands, I think it’s a decent introduction to the group, which reframes them in ways that make some interesting points but overlooks other important ones. It’s only towards the end where it really gets going, which is a shame but a good note to finish on.

I wonder what impact the close collaboration between the Tate and Munich’s Lenbachhaus had on the final shape of the exhibition? On the one hand, a secondary benefit of visiting Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider is that I feel like if I never make it to Munich, at least I’ve got a good sense of one of its museums. On the other hand, perhaps curating the exhibition without drawing primarily from one collection might have led in some different directions? Difficult to say.

But overall I still find this an exhibition worth visiting. If you’re new to Expressionism or Der Blaue Reiter, you’ll get to meet several of them. If you are interested in scientific or interdisciplinary art, you can rush ahead to the interesting bits at the end. And if you want to save yourself a trip to Munich, the Lenbachhaus has kindly come to you. All good reasons to come and see the Expressionists while they’re on show at Tate Modern.

Salterton Arts Review’s rating: 3/5

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider on until 20 October 2024

Trending

If you see this after your page is loaded completely, leafletJS files are missing.